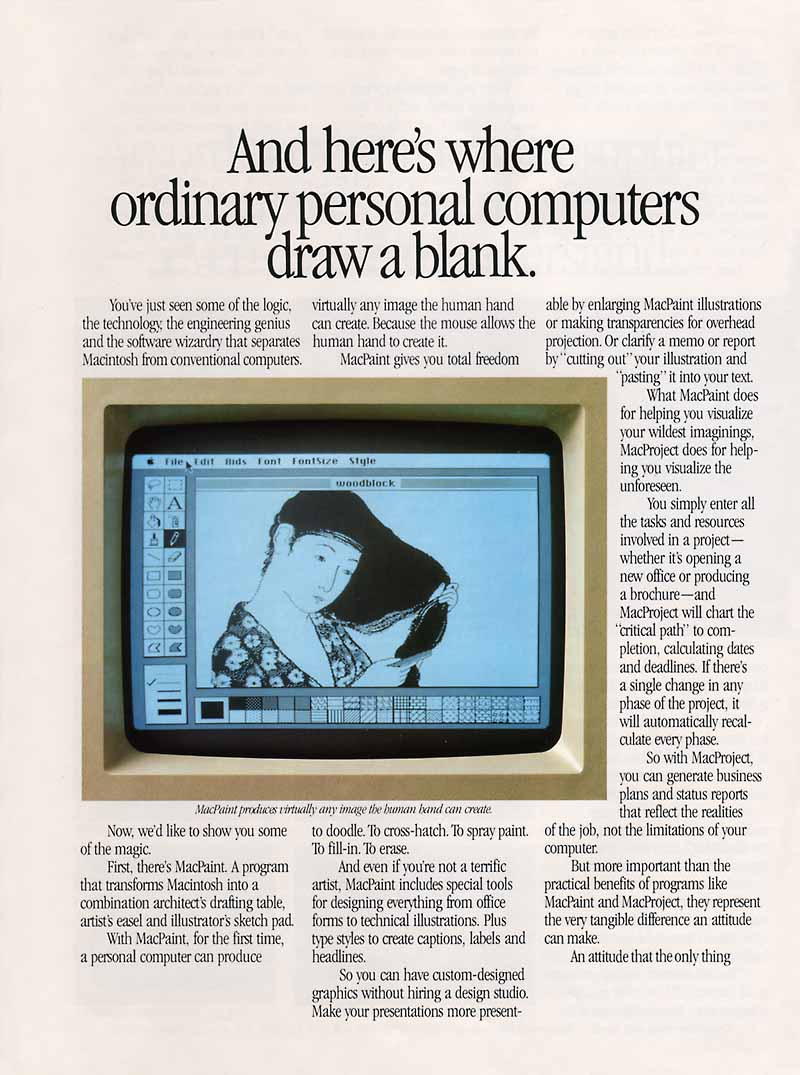

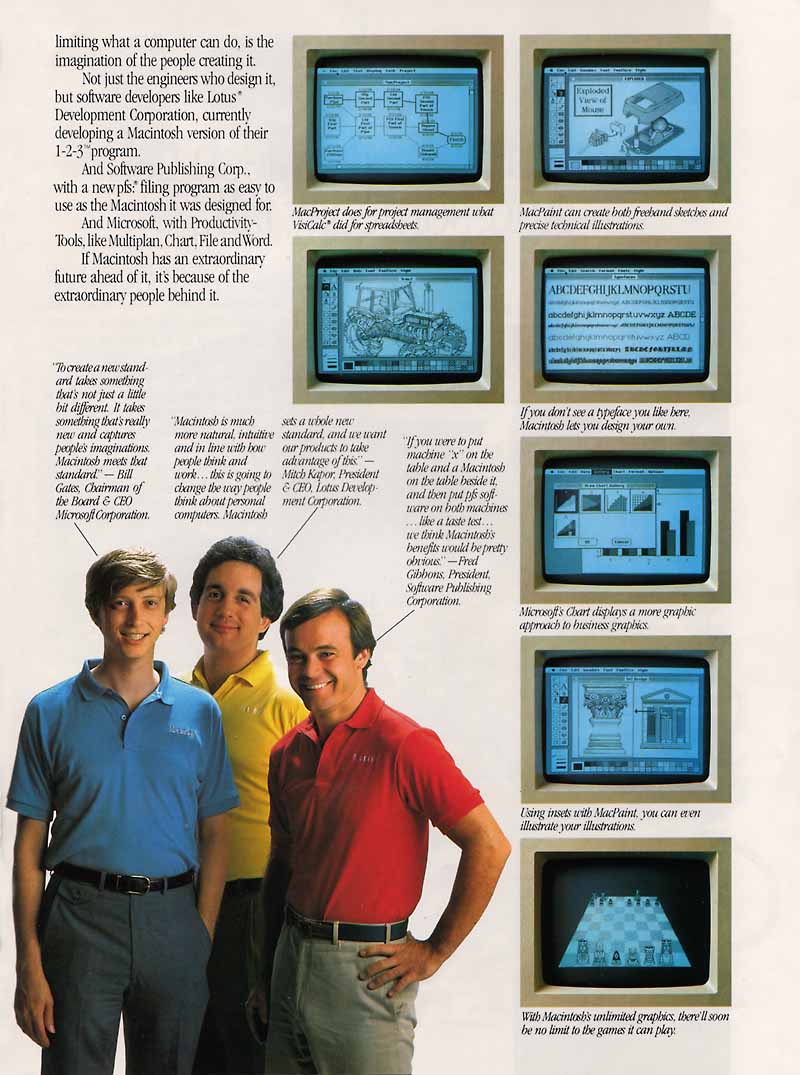

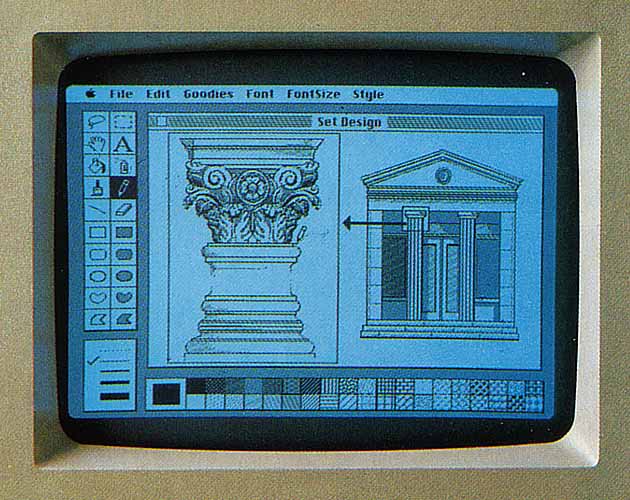

Readers of a certain age may remember MacPaint’s arrival well: developed by Apple and released in 1984 with the OG Macintosh Computer, it was our planet’s first taste of fancy graphics editing, and it was available to absolutely everyone. For a price, of course (the first Mac cost the 2019 equivalent of $5,000 USD). As technology advanced, it eventually fell to the wayside of new programs, and officially died in 1998. But then something happened. MacPaint found a new generation of artists that began to pick up that Paintbrush tool again and discover its powers. Now, there’s a rustling in the artistic fringes that has us asking: have we grossly underestimated this vintage tech as a relevant medium for art in the 21st century? Remarkably usable for a software older than most people’s cars, MacPaint looks like it’s just about ready for its renaissance…

When it dropped in 1984, The New York Times said MacPaint was “better than anything else of its kind offered on personal computers by a factor of 10.” Professional manuals, design plans, digital scribbles — it was all unfolding in the program. A year later, The Times was still singing its praises, calling it an opportunity for Average Joes to “[make] a mouse their scribe.” Or joystick. Yes, in case you forgot, there used to be a time when we used joysticks with our computers.

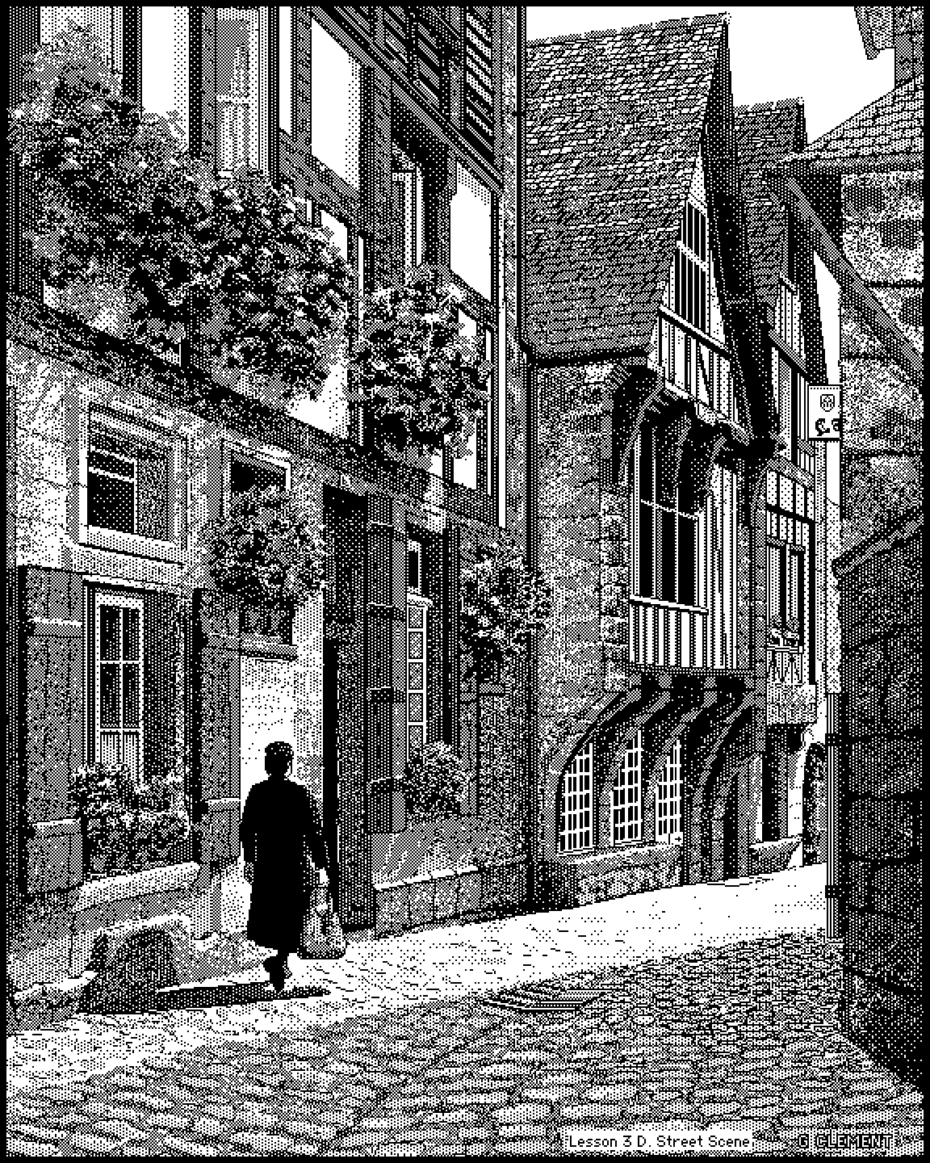

“It’s the ancestor of most modern art software,” MacPaint artist and archivist Joel Cretan told MessyNessy, “Most commercial art is digital now. The Mac allowed regular people to make high-resolution images. It was a major development in the graphic design world.”

He brings up the “undo” button, and how much we take it for granted, as an example. There is no clean “undo” button on a real pen, pencil, or paintbrush. “So, much of our current visual environment owes some debt to that software and the people who started experimenting with it,” he says, “[it] showed people, ‘hey, this is what computers can do now. There’s a new medium on the way.'”

Joel’s online archive, MacPaint.org, is also delightfully old-school in its homage to the program. The site is both a place for him to showcase his own experiments in MacPaint, and carve out a place for the naive art form in our cultural history, before it’s too late. “Many of them are just gone,” he says, “it wasn’t something people thought worthy of saving”.

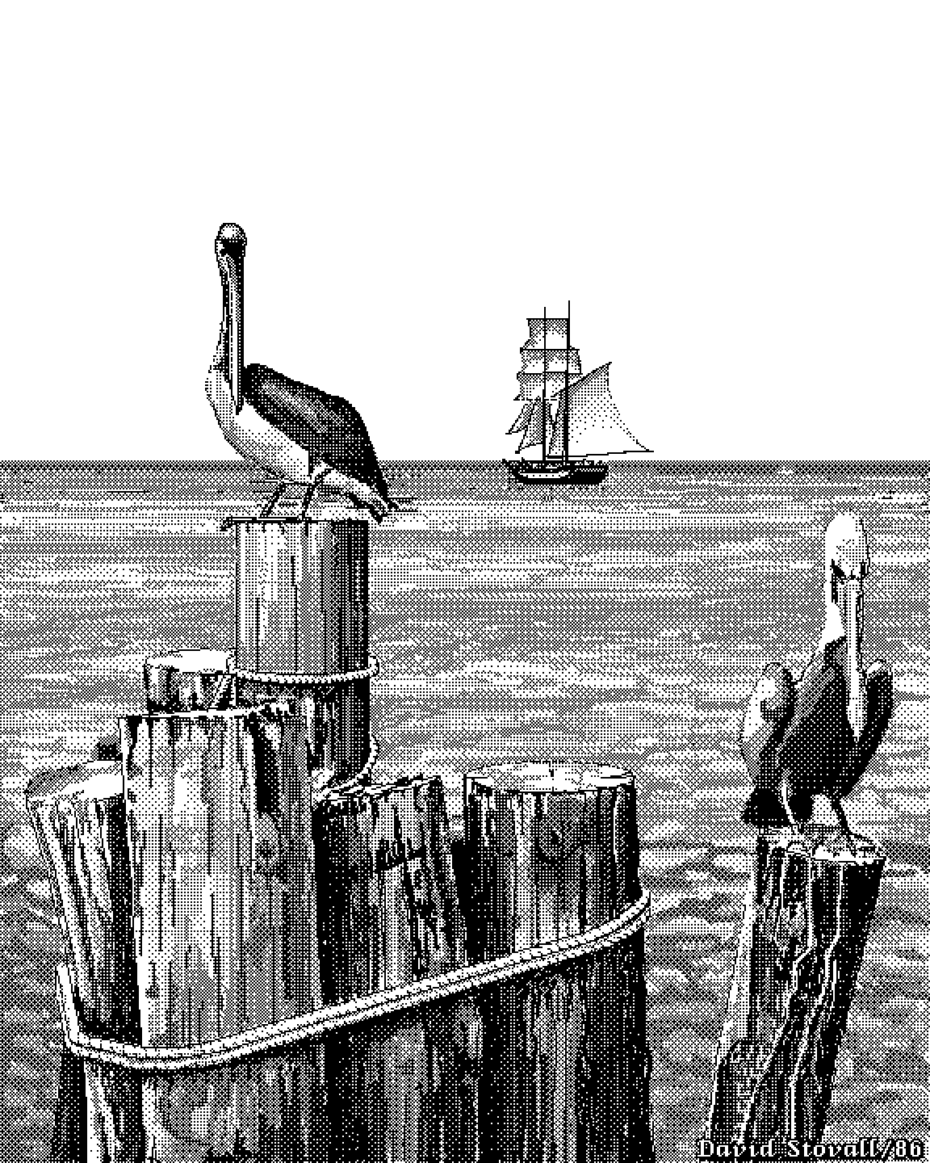

He features a lot of 1980s-90s artists like Laurence Gartel, Bert Monroy, James Leftwich and countless others who’ve created works that are now exhibited in major museums like the MoMA.

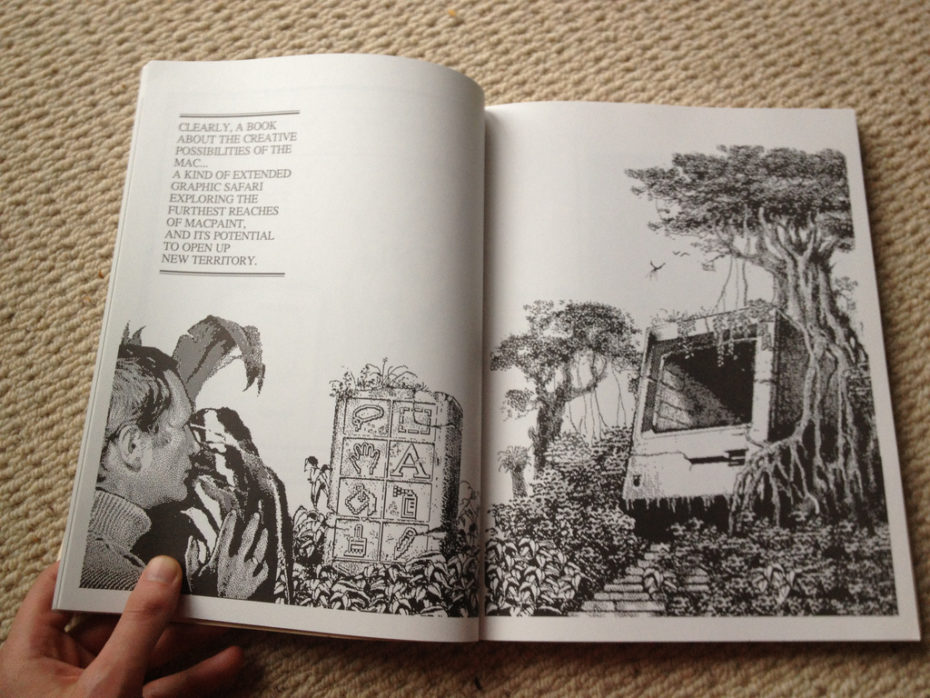

He also brings up the holy grail of MacBook literature: 1984’s Zen & the Art of the Macintosh by Michael Green, a book that was half practical guide, filled with examples of MacPaint illustrations, and half philosophical tome due to the trippy nature of its drawings that sent one resounding message: the era of computers is here, and it’s going to change how we relate to our environment. Michael Green, just like everyone else, was wondering how this new medium would change the balance of our daily lives overall.

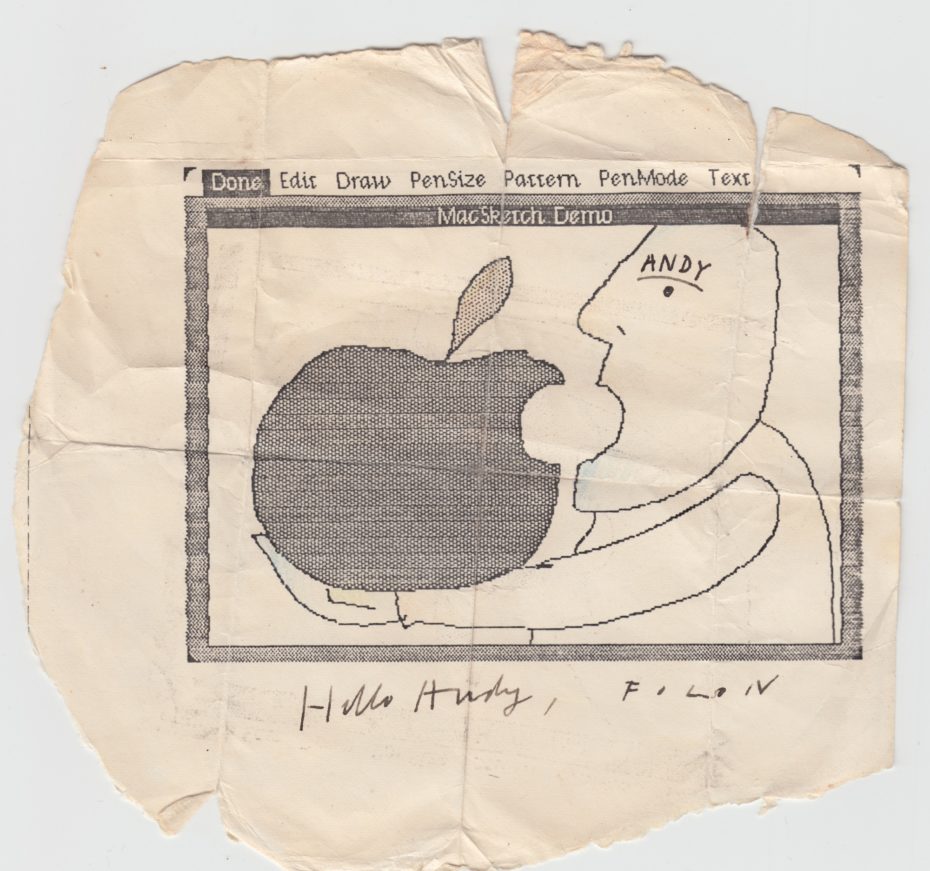

That Joel should talk about the fear of losing these images feels a bit counter-intuitive – isn’t it, well, just saved on a computer somewhere? Not so, apparently, as one weird little Steve Jobs side-story proves. Years before the launch of the program Jobs asked the famously tongue-in-cheek Belgium artist Jean-Michel Folon to create “Mr. Macintosh”: a little icon who would remain in the depths of the computer’s software, pretty much unseen except for when it would randomly surface to spook the user. The idea never came to fruition, but there wasn’t even a save function invented yet for the digital image — just a print function. So here you have it, the one and only true, printed copy:

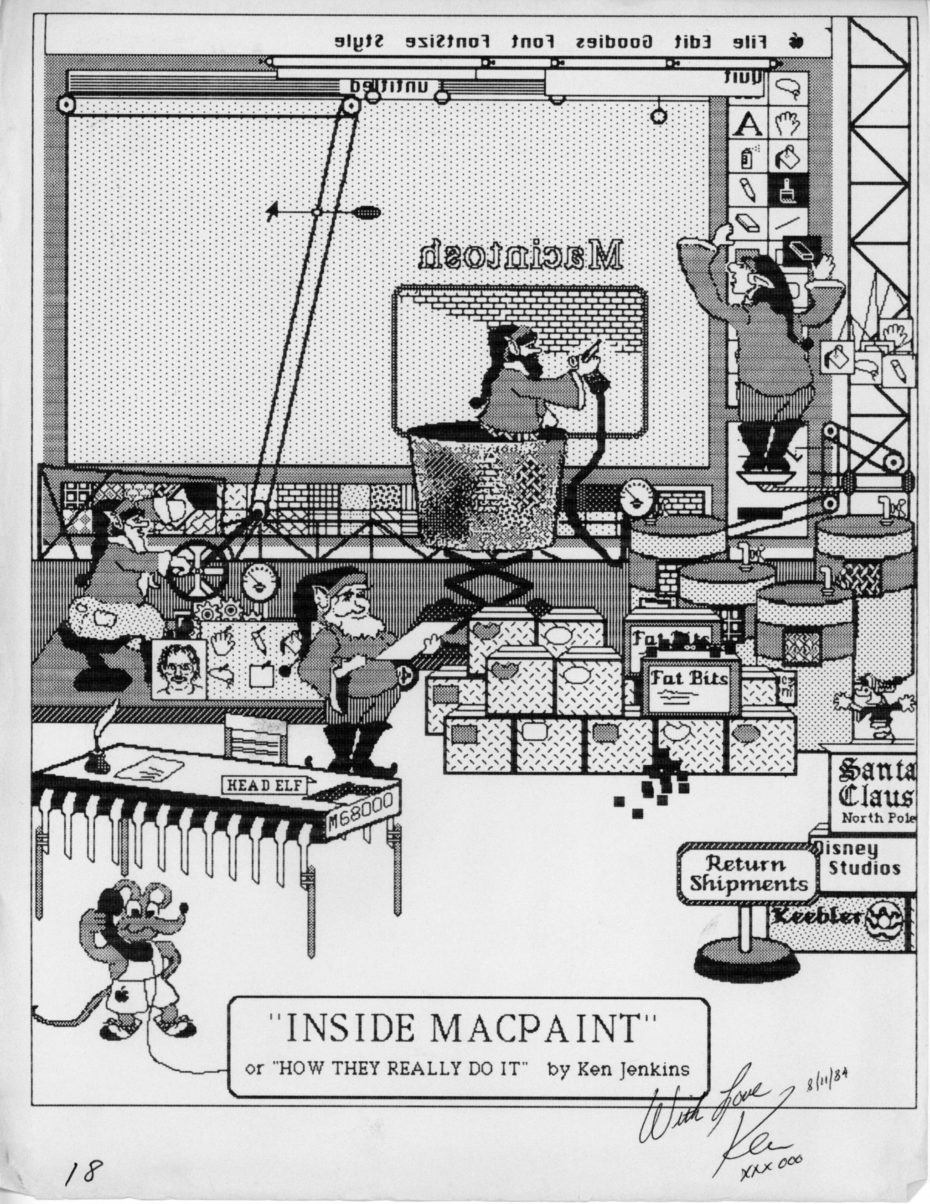

Even the random, amateur doodles you can find around the net are pretty great, and show how the new art form helped ordinary folks bring creativity into the most unexpected places, from the banal to the bizarre.

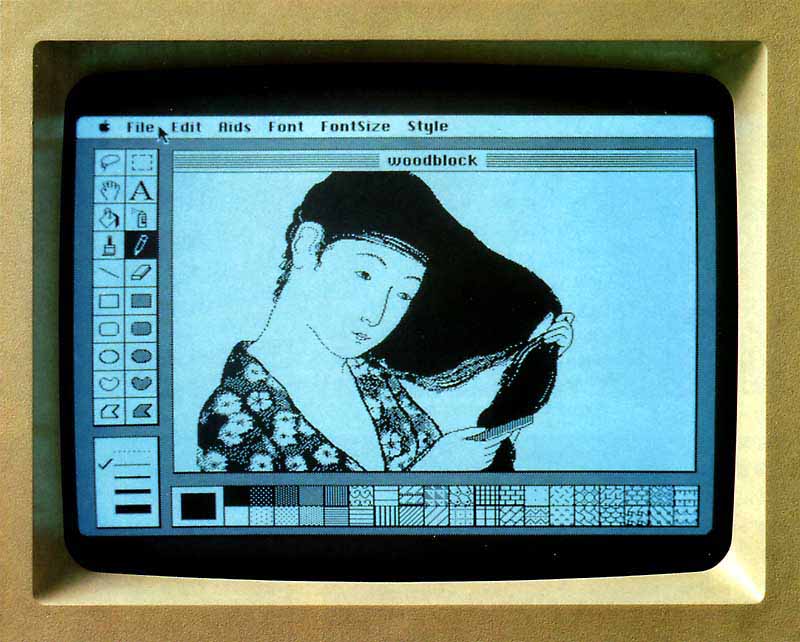

And as for that iconic MacPaint image of a Japanese woman used to market the Mac? It was made by Susan Kare, a brilliant member of the Mac team who actually developed MacPaint’s interface. The pixel painting was modelled after a Japanese woodcut belonging to Jobs.

MacPaint’s inevitable fall, of course, was due to the beautiful, but ruthless reality that technology charges on. Thus, the last version of MacPaint was released in 1988, and a decade later it was discontinued.

Today, the internet mourns MacPaint like a first love. “Photoshop is for the bourgeoisie. MacPaint forever!” writes one forum user; “MacPaint helped make me the person I am today,” says another, “Beautiful software for its time, revolutionary even. It helped cultivate my passion for pixels.”

These creators also don’t live solely in the margins of internet forums. They’re contemporary artists making waves, and they’ve turned to MacPaint as the best new, old medium of choice.

NYC based artist, Pinot W. Ichwandardi, captured Donald Glover’s dance from his “This Is America” video, using Macintosh SE computer, MacPaint software & MacroMind software. The result is quite astounding:

A multi-talented French musician and artist Mattis Dovier went as far as making his own “Twin Peaks” style music videos with MacPaint. “The graphics in this video are based on various influences,” he says, “the whole thing [takes] the form of a macabre poetry.”

Dovier has created several more music videos here.

And then, there’s possibly our favourite, the mysterious contemporary artist Uno Moralez. We reached out for comment, but to no avail (there are actually more articles about how hard he is to find, than there are interviews with him).

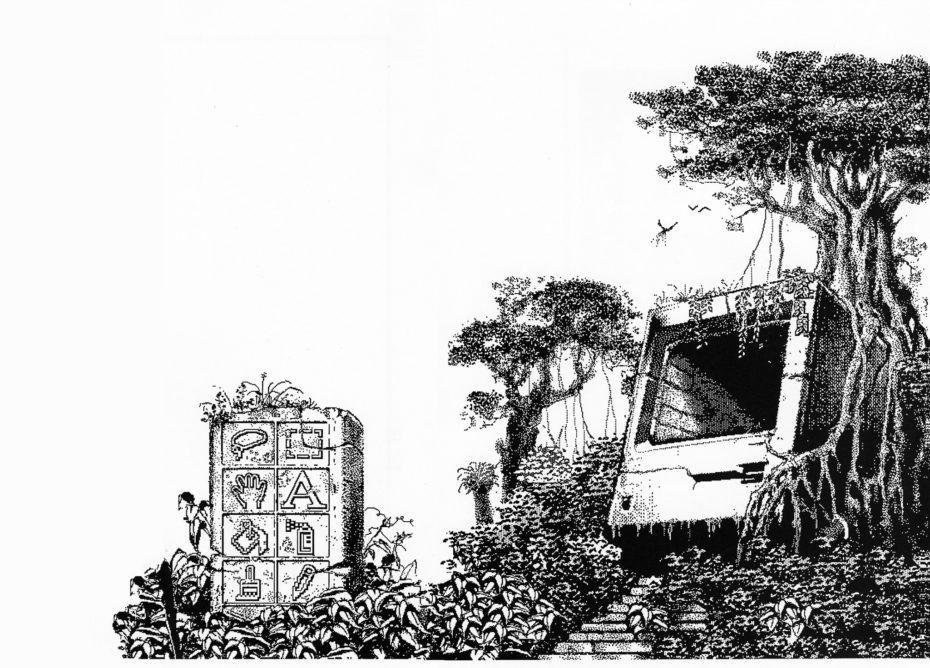

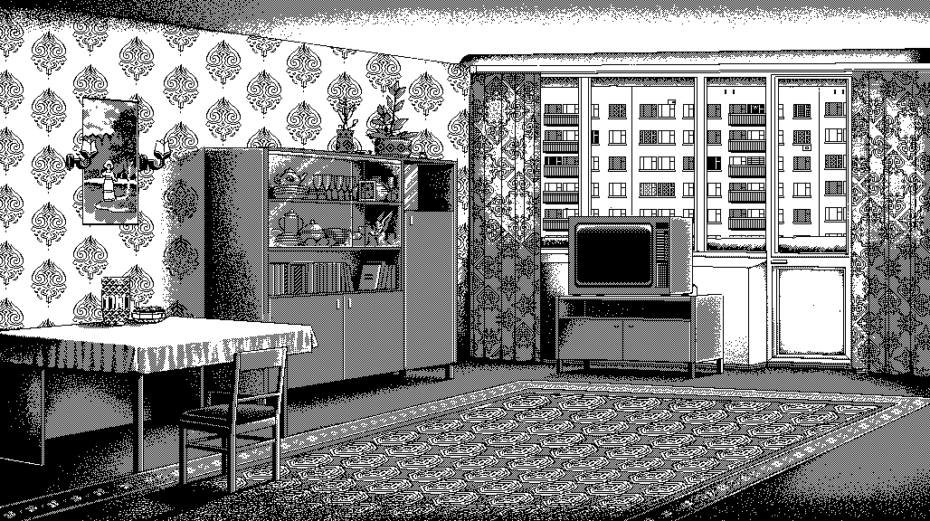

We’re calling him the “Dali of MacPaint”, and his work is basically like a cosmic film noir that unravels inside a Gameboy universe. It’s eerie, sometimes satirical, and even more fun when it’s animated:

Moralez is also proof that MacPaint isn’t just beloved by hipster millennials. For one, he’s not actually a latino named Uno Moralez, but a middle-aged Russian man living with his wife and cat. In the rare interviews he’s done, “Moralez” says his work reflects the inherent weirdness of growing up in Soviet Russia, as well as the boundless worlds he’d discover on the web.

He cites David Lynch, and Japanese animation as an influence. He says he insists on publishing his work on the web because it renders it accessible to so many people. Perhaps that’s the coolest thing about MacPaint, and why it continues to tug on our creative heartstrings.

It may not be the most sophisticated of mediums, but the final product speaks to almost all of us. We even asked Jerry Saltz, the Pulitzer Prize winning, sharp-witted Senior Art Critic for New York Magazine for his two cents. He didn’t know what it was, but wanted to, and after giving him our “universalist” pitch, said “it sounds fun”. And why isn’t that what art should be? MacPaint was born from a very democratic mission: to enable anyone to click that paint can icon and be an artist, whatever walk of life they may come from, and it goes beyond the brick-and-mortar museum to whatever dimensions it darn well pleases.

Our job now is to put in the effort to preserve its legacy. “Honestly, I would be surprised if it comes up all that often in 100 years,” concluded Joel, “It wasn’t state of the art for very long. But that’s why I wanted to create macpaint.org, to save that history so we don’t forget it.” Take that as your cue to get busy digging up old MacPaint pieces for his archive, or get cracking on some new drawings yourself. (Seriously, sites like CloudPaint, offer free tools to doodle to your heart’s content.)