Once upon a time, during the Cold War, Albania’s paranoid dictator Enver Hoxha forced his country to build 700,000 bunkers, one for every four citizens. Today, the country is still trying to figure out what to do with his concrete mushrooms that have become synonymous with the landscape. A number of them have been creatively converted into a variety of uses, from snack bars to museums, depending on their size, but most are still abandoned, lingering as constant reminders of a bleak chapter in recent history. Some cities have a litter problem, some suffer from high crime rates and others might have a lack of affordable housing – these are problems we have lots of answers for (even if they don’t always work). But how do you undo the “bunkerization” of entire country?

First, a little crash-course in the bunkers’ communist context. They were a project undertaken by dictator Enver Halil Hoxha, who effectively isolated the country from Western world during his rule. The unfolding of his vision, unfortunately, mirrored so many other cases of communism in practice: industrialisation thrived, but so did forced labour camps; the literacy rate skyrocketed, but so did the amount eerie experiments, and extrajudicial killings. Hoxha didn’t just “deal” with traitors to his regime, but carried out targeted executions on citizens who were still imprisoned by the tens of thousands into the 1980s as Hoxha himself ruled up until his death in ’85.

The bunkers were feverishly built between roughly 1970-80 for an invasion that would never come. From a young age, Albanians were taught to prepare for guerrilla warfare on their doorstep, warned they must be “vigilant for the enemy within and without”. In Albanian, paranoia became a bit of a patrimonial pastime.

Hoxha had crowned himself the country’s saviour, and went by haughty nicknames like, “The Great Teacher” and “The Sole Force”, and used the bunkers to remind citizens that their safety was always in his hands – or at his mercy. If anyone dared to defect, they had to brave an electrically-wired metal fence 600 metres from the border, and face certain death.

Approximately 700,000 bunkers were built, varying from machine gun pillboxes, to a large underground hideout in the capitol of Tirana. After the fall of communism in December 11, 1990, the creepy, concrete mushrooms remained on every corner – at gas stations, backyards, schools, beaches, you name it, there was one in every size (the smallest were single-occupant bunkers). Hoxha’s statue had been pulled to the ground, but for Albanians the bunkers were a painful reminder of his mind games. It was better, it seemed, to let them crumble and drift away…

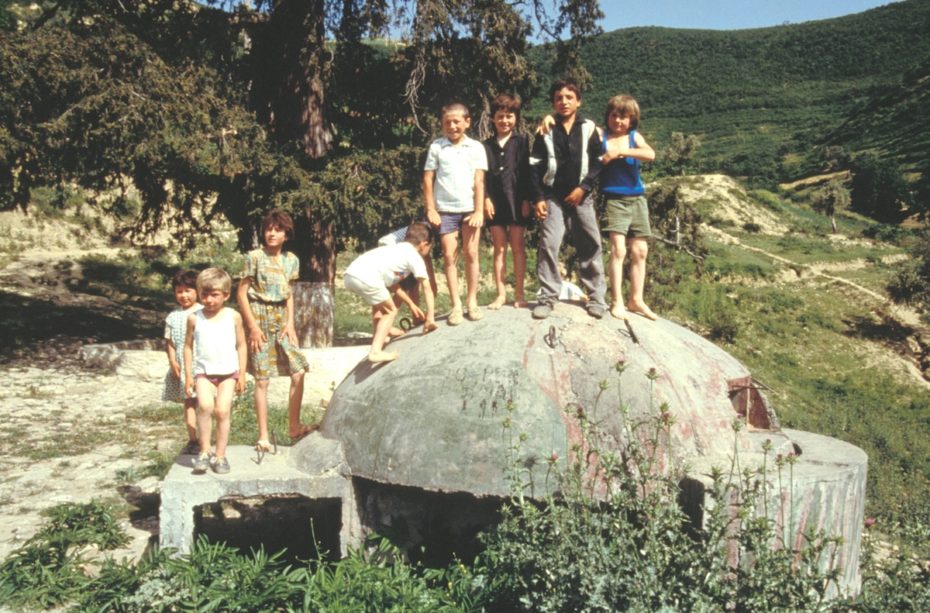

They were often stripped of their sell-able structural materials by citizens and repurposed as farm “sheds”, temporary housing, or even makeshift playgrounds for children.

“There are just so many that they have become accustomed to their presence, much the same as a Londoner with red telephone boxes or New Yorkers with yellow cabs,” says photographer Robert Hackman, who has extensively photographed the bunkers.

The past decade has also seen some Architetural Digest-worthy proposals brought forward by designers who hope to turn them into “Brutalist-chic” Hobbit Holes. Non-profits such as “Project Bed & Bunker” proposed mock-ups to transform the dilapidated bunkers into eco-friendly bed and breakfasts:

in 2012, they completed their first prototype for a backpacker’s hostel, but since then, the concept doesn’t appear to have taken off with local developers. The university-led Bed & Bunker collective tells us they are still investigating the potential for bunkers in Albania.

The sheer volume of these bunkers makes it impossible to transform every last one, particularly as costs for restoring them (and destroying them) are so high. Still, some do find a way of turning a small profit as fast food bars and restaurants…

Meanwhile in the capital of Tirana, Bunk’Art is a museum and gallery space that straddles the line between its past and present:

Here, you can get a tour of the bunker that was built with its own cinema house, no less. There are about two-dozen preserved rooms, all showing what it would’ve been like to bunk underground as Hoxha in relative luxury. It also doubles as an active community space.

Bruno Vanbesien

There’s no one right way to live with relics of a painful past. For some, wiping away those vestiges offers fresh start, and a cathartic move towards the future; for others, reclaiming and repurposing these once sinister mushrooms may be empowering. Given that there’s hundreds of thousands left for grabs, we’re curious to see where they go next in the future. Any ideas?

In the meantime, take a look at the work of Robert Hackman, documenting Albania’s bunkers.