Greetings from Shingo, a rural village, 650km north of Tokyo that is believed by its inhabitants to be the last resting place of Jesus Christ. Make the pilgrimage to its quiet hills, and you’ll find yourself in a veritable slice of the Twilight Zone where the Christian prophet led a double life as a garlic farmer, had three daughters, and lived out his days there until the age of 106 – all details that are fully explained at the local “Jesus Museum”. So let’s poke our head around Jesus’s Japanese pied à terre. Who knows, we may just run into a few of his descendants…

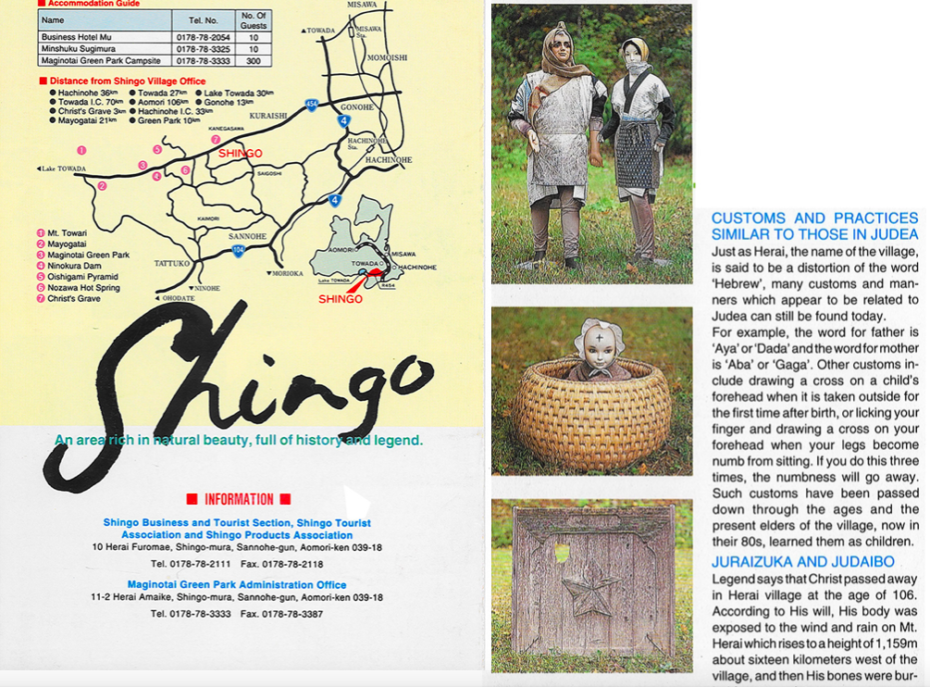

Shingo is situated in the Aomori Prefecture, and has a population of roughly 2,500. Next to Christ’s alleged burial plot, the most popular tourist attractions are a bumper car racetrack, an underwhelming pyramid, and very large rock (aptly called, “the Big Rock”). At least, these were the takeaways when ABC reporter Jill Colgan visited Shingo years ago. “It seems extraordinary that a town of non-Christians should be so taken with Christ,” she says, “but there’s a very good reason for [them] to believe”. Tourism.

She’s not wrong. But the legend of Shingo-Jesus isn’t just a gimmick – it’s something locals truly believe. The story goes as follows: Jesus, at 21-years-old, travels to Japan where he studies under a priest on Mt. Fuji. At the age of 33, he travels back to his homeland to sing the praises of his newfound Eastern wisdom and is instead met with a bunch of angry Romans. No worry, however, because according to a plaque by his burial site, Jesus’s supposed younger doppelgänger brother, Isukiri, kindly offered to step in for him and take Christ’s place on the cross. Jesus decides it’s time to go back to a life of exile in Japan, and takes his brother’s ear and a lock of his mother’s hair as keepsakes. Today, the adjacent, identical burial plot in Shingo is believed to contain the mementos (hence the two graves).

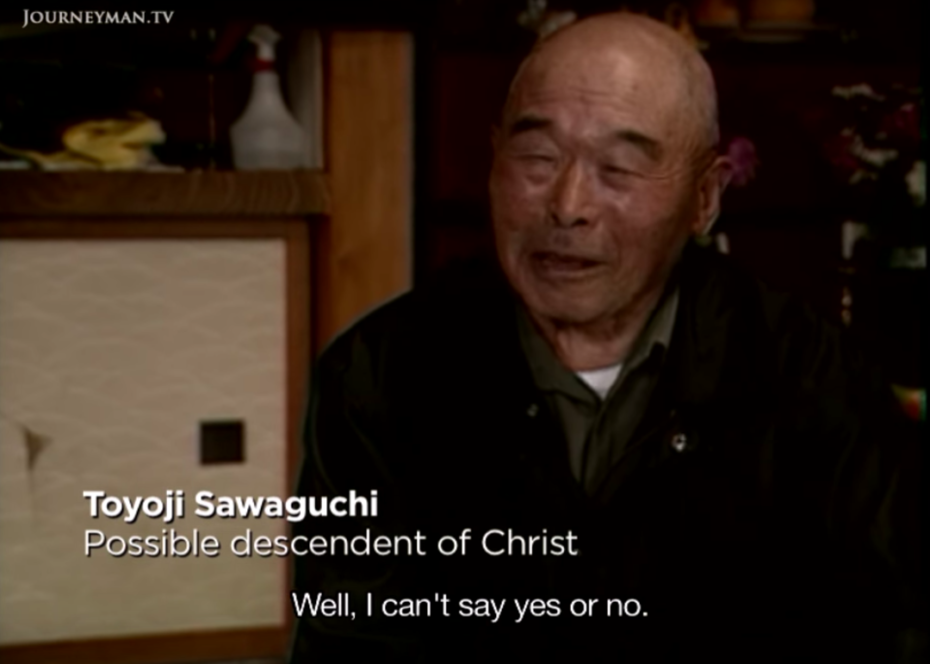

In Shingo, Christ was believed to be “a great man” but not necessarily a performer of miracles. Instead, he adopted the name Torai Taro Daitenku and started a family with a woman named Miyuko. The direct descendants of that bloodline today belong to the Sawaguchi family, who has looked after the burial plot ever since and refuse to dig it up to either confirm or debunk the legend, partially because they seem a bit indifferent about the whole thing…

Still, there’s a museum by the burial plots that provides information and evidence of the village’s claim to fame. Due to Jesus’s presence, it says, locals began wearing Jerusalem-worthy garb and carrying their infants in baskets worthy of Moses. As late as the 1970s, residents would put charcoal smudges on infants’ foreheads. Interpretations of the Star of David are also present throughout the town, and the local dialect is coloured with Hebrew-like words.

Locals always regarded the Sawaguchis as a curious bunch; many of them had blue eyes and an odd family heirloom: a mediterranean grape crusher. Yet, when implored about their potentially holy bloodline over the years, they shrug off the matter, telling reporters to “believe what they like”. It doesn’t make much difference for the Sawaguchis who are, after all, of the Shinto and Buddhist faiths. The prevailing legend of expat Jesus, however, brings a degree of tourism and vitality to the region. Every June, people gather to celebrate with a big old picnic by the burial mounds singing Hebrew-Japanese folks songs. It’s all a part of the “Bon Festival”:

Is there any, even the tiniest sliver of truth to the legend? There is an “unaccounted for” 12-year gap in the New Testament. At one point, there was supposedly a real biblical relic to back-up the story, the Takeuchi Scrolls, which surfaced in the 1930s but disappeared in WWII. The “Christ Museum” in Shingo now has transcriptions of the lost documents that only the oldest locals remember.

Most historians chalk-down the legend to a sensational publicity stunt pulled by the mayor of Shingo in the 1930s, Denjiro Sasaki, who simultaneously, and rather conveniently, revealed the discovery of various ancient pyramids (see the aforementioned “Big Rock”). But rather than dissolve with time, the story has only become more and more woven into the identity of the town where Buddhism prevails, which may be one of the reasons for its success.

Christianity here is not a religious practice, but a means to have a picnic. It fuels the economy through tourism, and chooses to celebrate a man they see not as the son of God, but a professional do-gooder (i.e. local legend recalls Jesus traveling very long distances to find food for villagers). He was big in Japan, but he was no prophet.

Have a look around Christ’s Japanese grave site here.