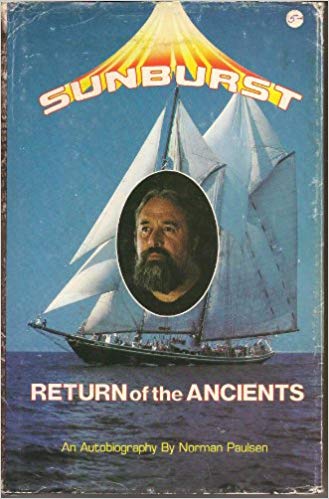

They came from the mountains, and kept to themselves. If you were lucky, you might have seen them frolicking in the hills under the glow of the buttery, golden hour sunshine that California does so well. Collectively, they were known as “The Brotherhood of the Sun,” and in the 1970s, they emerged as one of the most successful communes in US history. In a manner of speaking, that is, because if we’ve learned anything from our past investigations into communes and cults, it’s that these sort of things have an expiration date. Otherwise, things get ugly, which is why we were surprised to learn that the Brotherhood not only existed, but turned into “Sunburst Farms”: a multi million-dollar business. This is the story of how one man’s dream gave birth to a Californian Camelot, a trip steeped in idealism and salvation, complete with stallions, schooners, and firearms. But most of all, it’s a fascinating tale of what happens when peace, and making a profit, collide…

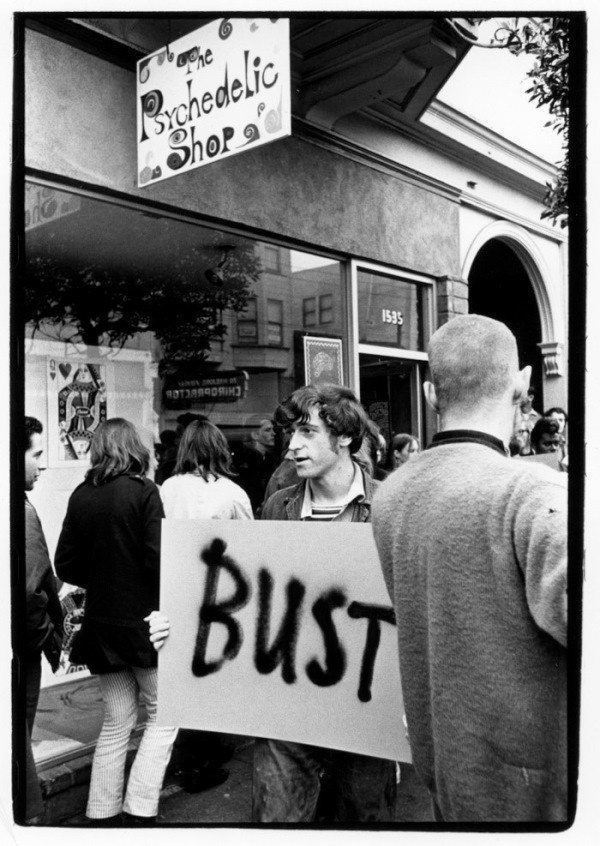

Our story begins in a Southern California psych ward in 1963. Local bricklayer Norman Paulsen was trying to calm the voices in his head at Santa Barbara County Hospital after an overdose on his medication; the same voices that would return to him six years later, prompting him to found a haven away from the mounting anxiety of the era. “The center was not holding,” writes Joan Didion about the fall of the 1960s in Slouching Towards Bethlehem, “It was a country of bankruptcy notices and commonplace reports of casual killings […] People were missing. Children were missing. It was not a country in open revolution. It was not a country under enemy siege. It was the United States of America in the cold, late spring of 1967.” The Haight-Ashbury overflowed with pre-teen junkies, and the Tate murders gave the counter culture a serious ice bath. Flower power was at its tipping point when Paulsen tried to give the dream one last chance to work.

To really understand the complexity of the 1960s, we recommend watching Ralph Arlyck’s 2005 documentary, Following Sean, whose plot finds more parallels than you’d think with Sunbursts’s story. The movie combines footage from 1967 and 2005 of a hippie boy, Sean, who fascinated Arlyck when he lived in San Francisco. At barely four years old, he waltzed around Haight Street barefoot, and talked about smoking weed. Truffaut was fascinated, and called Sean “a kid of our modern times”, while the White House (which had a private screening) was horrified. Folks predicted he’d become a genius stockbroker, or an addict. Whatever his future held, outsiders thought it would fall into one of two extremes, but couldn’t necessarily see a place for “hippie” culture to become integrated into the norm. That’s where Sunburst becomes interesting.

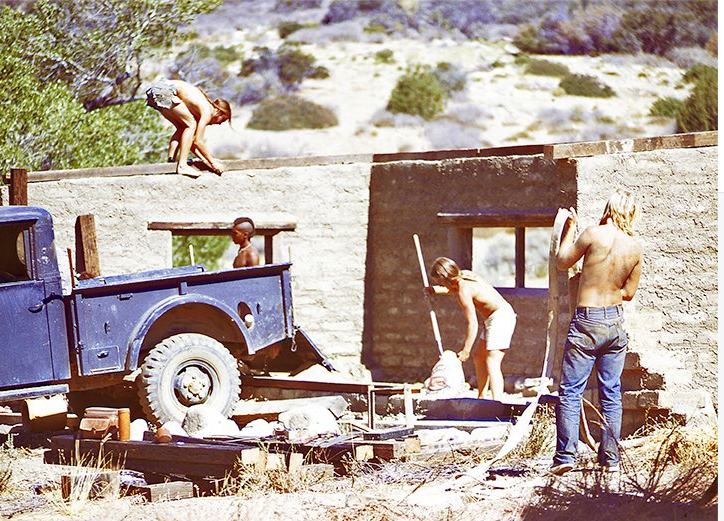

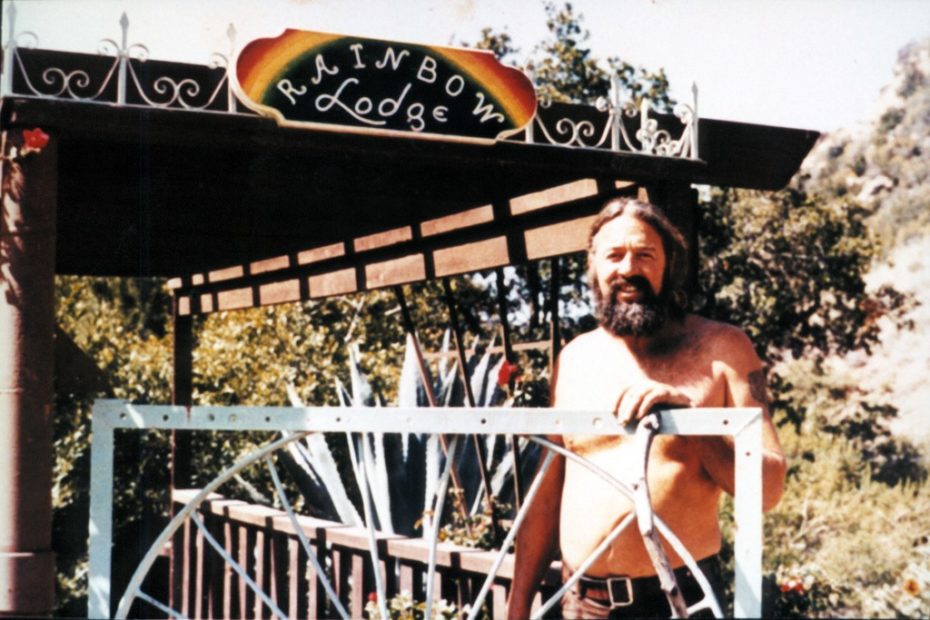

Paulsen began leading meditation sessions at the end of the ’60s in an old ice cream warehouse in Santa Barbara. Soon dozens of young folks from all walks of life made it their mecca. By 1971, he’d amassed hundreds of followers and moved to a nearly 160-acre ranch where they built teepees and adobe houses, planted orchards, and herded Nubian goats and French Percheron horses (the sturdiest of stallions). The goal was to consume cleanly, and only what they needed.

There was a strict no drugs, no outside possessions, and no sex (outside of marriage) policy. A member named Mehosh Dziadzio captured some beautiful images of the period, and his snapshots paint a dreamy picture of Sunburst during its glory years. “Before we started our day, we would join hands in a circle to thank Mother Earth for the bounty she has given us and pray for the healing of our precious planet, much like the native peoples who came before us,” explains Dziadzio, now a professional photographer, on his website. “With self sufficiency as our goal, we learned all the skills and the trades necessary in working with the land. From cowboys to sailors, blacksmiths to weavers, store keepers to bee keepers…”

They were such busy bees that they started selling their produce to local establishments. “Their image in the community was quite wholesome for a long time,” explains Ernest, a Santa Barbara resident for over 40 years, “They were way ahead of their time with nice fresh organic fruits and vegetables (great avocados for 10 and 25 cents) granolas, and fresh carrot and vegetable juice on order. Their markets were funky but clean, pleasant to go in.”

“It was a different time,” Patty Paulsen, a member of Sunburst since 1975, told us over the phone, “I was from the East Coast, but I felt this calling to California. You couldn’t not follow it.” Like the majority of the Sunburst followers, she was in her twenties and looking for a way of living that, she says, deepened her understanding of “living with awareness and in a connection with one another”.

She recalls that they ran a little café, “the Farmer and the Fisherman”, a bakery, and eventually had a wholesale warehouse for shipping their produce across the country under their newly adopted title of “Sunburst”. They came out with a veggie-centric cookbook taught, “How to Get Protein Without Really Trying”, and had a domino effect on other local businesses in the area to go green. Come April of 1975, they were a $3 million business that, according to an archival article in The Los Angeles Times, had a school for members’ children and a 3,000-acre ranch adjacent to land owned by Ronald Reagan and John Travolta”. It was the largest organic farm in the USA.

“I don’t know what it was,” Patty says when asked about what made the commune work, “It was something in the air. Something about being young, too.” She pauses. “I think that when people hit age 28, something happened. They either stayed or left, but something about that number brings in a big change – not always bad, you know. But not always good. We were like a family”.

Ernest’s perception of the family, however, was that it really kept to itself. “They were so insular nobody really knew what went on in their culture when they were back at the commune,” he said, “They were driven in school buses into their Sunburst Market stores every day. We would try to talk to the girls at the check out, they just smiled and did not respond. [They were] all in hand-made tie dye clothes, long hair, barefoot.” He recalls an odd run-in with their members when he was a carpenter, when the city demolished old baseball field stands. He says he went down with some friends to help take it apart in exchange for some scraps, but “the Sunburst guys showed up in a big group and aggressively laid claim to big chunks of it, demolished it like maniacs and loaded it on their trucks.”

“People didn’t always understand,” says Patty about the tension between the commune and the community at large, “you hear the word ‘commune’ and you think of all these extremes that just weren’t us. Everything has its ups and downs, its roses and thorns. It’s up to you to dwell on either the thorn or the rose”. When asked about the financial ups and downs of the commune? “Well the company didn’t go public,” she says, “and in the late ’70s and ’80s… those were some hard times”.

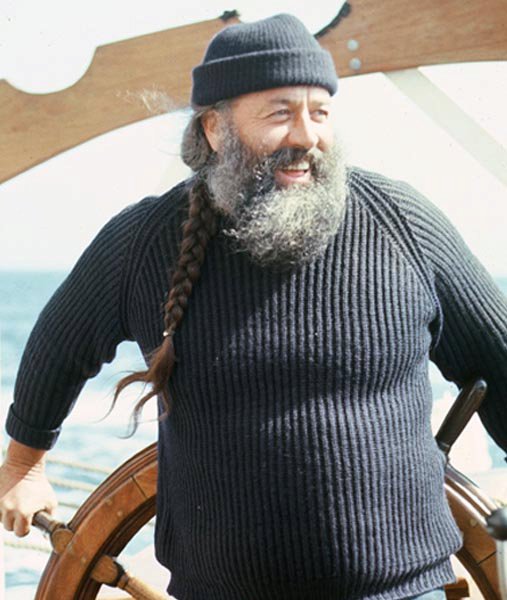

Hard times is an understatement. The police “discovered that they had a stash of serious weapons up on Gibralter Road at a strategic bend,” explains Ernest, “with a plan to close the road when some doomsday event they thought was imminent happened. That was the end of the party for the stores.” They found M-14 military and Belgian assault rifles, which Patty says they purchased not as doomsday effects, but to defend themselves against intruders in the then isolated mountains. Paulsen also bought and spruced up 1920s schooners, which he chartered to the local islands with members.

The commune, it seemed, had no trouble standing on its own two feet away from the conventions of the city. “There was also a guy, a member who was a Green Beret,” says Patty, “who Norm had people train with. Not everyone liked that.” It’s a subject Patty is touches on openly, but doesn’t dwell on for long. Even less so, when the topic of Paulsen’s mounting drug addiction comes into play.

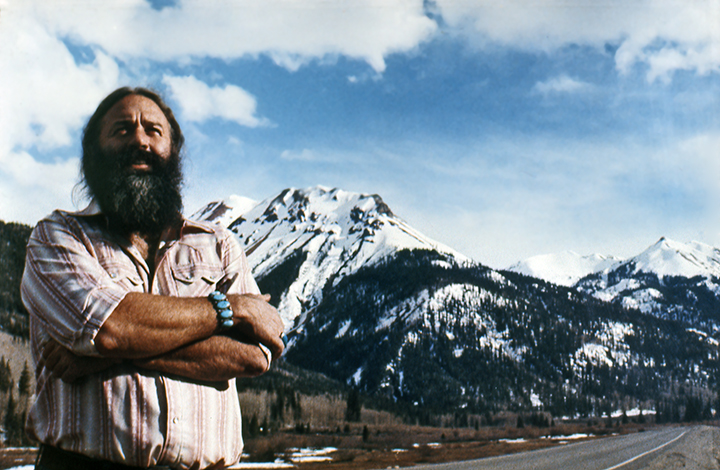

Paulsen, who passed in 2006, was a curious man. Patty talks about him lovingly, as a leader who inevitably “had to carry the responsibility of a vision” that was bigger than himself. His backstory, too, has all the eclectic trappings of a 20th century prophet; he was the son of a blind judge from Lompoc, Charley Paulsen, who played piano at the local silent movie theatre. As young man, he survived a 30-ft fall, and began seeking spiritual guidance through the teachings of Paramahansa Yogananda, the man who brought yoga to America.

“Beginning in 1920, Yogananda was one of the first masters to bring meditation and yoga science to the United States,” explains Sunburst on their site. “He came from a rich lineage of enlightened teachers, beginning with the great master Jesus working in conjunction with the ageless Himalayan yogi Babaji”. When Paulsen bought the land for the original commune – thanks to a $6,000 from a workers’ compensation settlement, and $50,000 from his mother – it was as the torch bearer for Yoganada, and, as Patty says, one simple goal: “to meditate together”.

As early as 1971, Paulsen declared the Brotherhood to be a Christian non-profit despite the fact that the commune was a mix of Christian, mystic, Kriya Yoga and indigenous tribal beliefs (couldn’t hurt in terms of achieving a tax-free status). By the late 1970s, Sunburst communities had expanded to cities in Utah, Arizona, and Nevada, while Paulsen burned through their earnings on alcohol and drugs. A 1982 Drug Enforcement Agency investigation found that he’d spend $60,000 on narcotics, while members – who were defecting left and right – said it was upwards of $200,000. In a 1986 interview with the LA Times, former member Michael Ableman recalls the day he left. “Norm was sitting in his house, in a very dark room, with his shirt off, and he was quite drunk. He said to me: ‘I am the man they call Jesus of Nazareth. If you believe me you can stay. If not, get out.’ I was told to be out of there by the next day.”

The disparities between what higher-ups in the commune were earning, compared with what those who were farming during 12-hour days, was also of concern. Paulsen was driving fancy cars and buying silver horse saddles. “He wasn’t a drug addict,” Patty says defiantly when asked about Paulsen’s spending. “There were no clear instructions back then like today, no internet, when you were taking medication.” In the same interview with the LA Times, Paulsen chalked down his drug use to his years of absorbing everyone else’s energy. “You can’t sit down and talk to someone without exchanging energy with them,” he said. “If that person has negative thoughts, that leaves a residue of negative energy on the one who’s trying to help. All that took its toll on me.” In the game of revisiting such complex history, the truth tends to live somewhere between the extremes.

Patty changes the subject back to meditation. It’s clear that now, after all these years, the community has pardoned Paulsen by way of sweeping the painful parts of his past far, far under the rug. His smiling face appears frequently on their Facebook page — the emblem of their martyr, but also, family member.

For over two-dozen die-hard brethren, hope remains. The 1990s saw Sunburst’s return to California, and about a dozen miles southeast of Lompoc and at Nojoqui Farms, you’ll still find their community camped out in what arguably looks like paradise at Sunburst Sanctuary. “We have about 30 old timers still here,” Patty says. “We’re still farming, but it’s for ourselves.” They’ve even got a website that explains everything from their online courses in meditation and yoga retreats to a paleontology workshop, involving a hike to view onsite fossil specimens at the Sunburst Sanctuary. Books by Paulsen are also still available from the website.

The future of Sunburst remains uncertain. On so many practical levels, the community has its hands tied by its classification as a religious organisation on an agricultural preserve (bringing in new members is hard, when you can’t build the structures to house them). Yet, the degree to which Sunburst has carved out a place for itself online and in social media is impressive. Patty says that anyone is welcome to attend their Sunday service, which is non-denominational and gets to the heart of what Sunburst was always about: making the time to meditate together.

“We have one last store here in Solvang, [California],” she says, referring to the last vestige of what basically became hippie entrepreneurialism. Firearms, etc. aside, there’s something to be said about the commitment and devotion to the ideal of community and how long some followers are willing to carry that dream into the next generation. The media would have loved to see the entire commune brought to its knees – and indeed it was, on several occasions. Yet, Sunburst remains remarkable for avoiding the extremist fate so many predicted for counter-culture groups in the ’70s (selling out, or burning out). It was, and still is, a happy anomaly — and there’s no way to neatly tie up their story in a bittersweet bow, simply because it’s not finished being told.