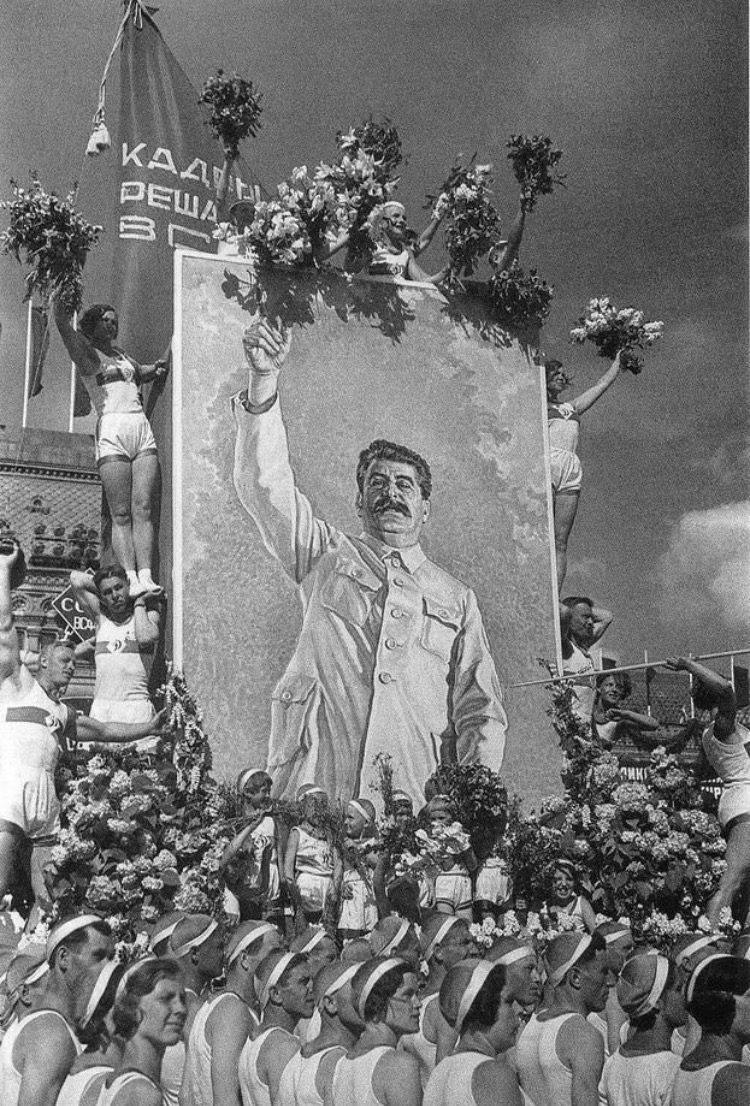

For many, “Soviet fashion” reads like an oxymoron. One simply can’t imagine that funding fashion ateliers was high up on Joseph Stalin’s to-do list, and it wasn’t, but still — it was there, and apparently it was utterly extravagant. “Eclectic mannequins were turning slowly as they displayed rather bewildering clothes,” wrote Elsa Schiaparelli of the designs, “Or at least these clothes bewildered me.” There were furbelows, pleats, and “an orgy of chiffon” (her words, not ours). Russia was now under the iron fist, so why on earth was it literally grasping at such creative threads? As a new dictator, Stalin wanted to put forth a distinct image of the Soviet woman. She was a clear poster-child for the USSR, she had to look better than good. She had to look modern, which is precisely why he launched his own fashion house in 1935: Dom Modelei.

By the 1930s, Stalinist Russia was in full-swing for better and for worse. We all know about the “worse”, but on paper, industry was booming and new policies championed female voting, reproductive rights and expanded opportunities for women in the workplace. As early as 1917, ‘Working Women’s Day’ was declared a national holiday, which the UN wouldn’t even recognise until 1975. That’s pretty much our short-list for the joys of Stalin’s vision for Russia. Today, his name is synonymous with infamy, genocide and just general suffering. Which is why into the 1980s, this is what the words “Soviet Fashion” brought to mind:

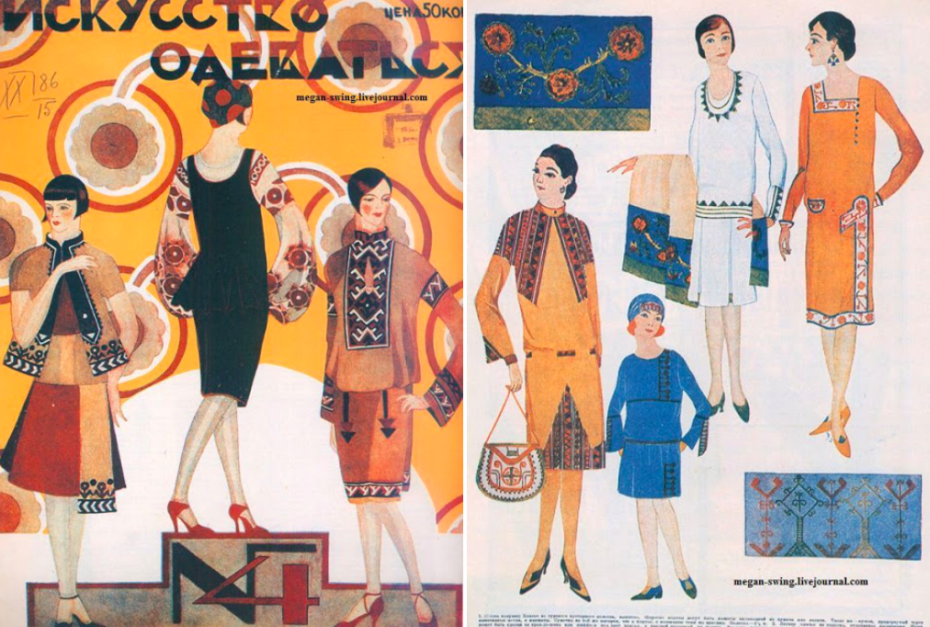

In truth, Soviet fashion was majorly inspired by the tone of the USSR’s first official women’s magazine, Rabotnitsa. The journal was dreamt up by Lenin and a group of ladies who wanted to create a resource for the Soviet brand of femininity, and it screamed, ‘‘You know what? A woman can drive a tractor just as well as she can boil potatoes.’

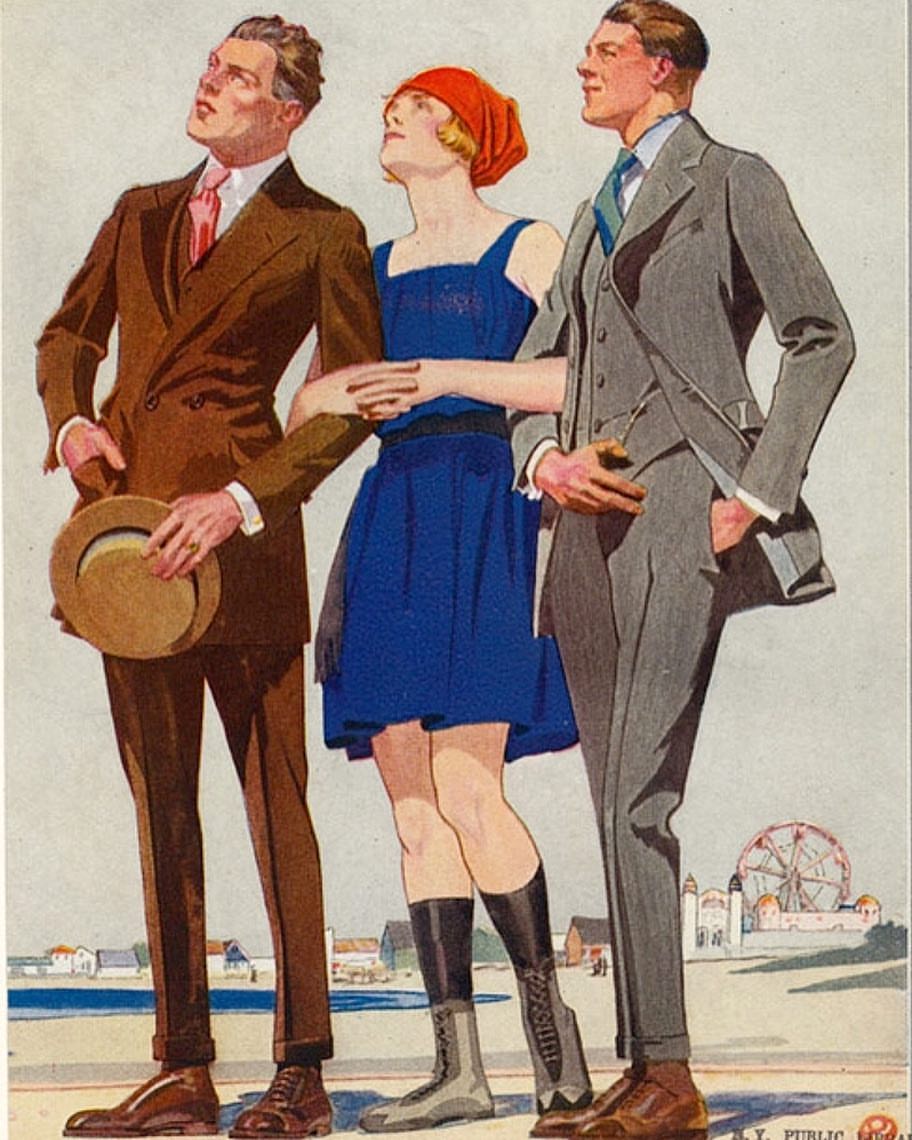

If Rabotnitsa was presenting any kind of fashion, it was practical fashion. Boots, longer skirts and dresses were the order of the day, and scarves to tie back your hair, preferably in that good old shade of Communist red.

These were women on a mission to make sure the country didn’t regress back to its painful power dynamic of giving the bourgeoisie everything, and leaving the working class with nothing.

But however steel-willed Stalin was, even he couldn’t deny the power of style. The most effective propaganda has the shiniest of patinas, which meant that the whole grey-on-grey-on-red mood board just wasn’t cutting it for morale.

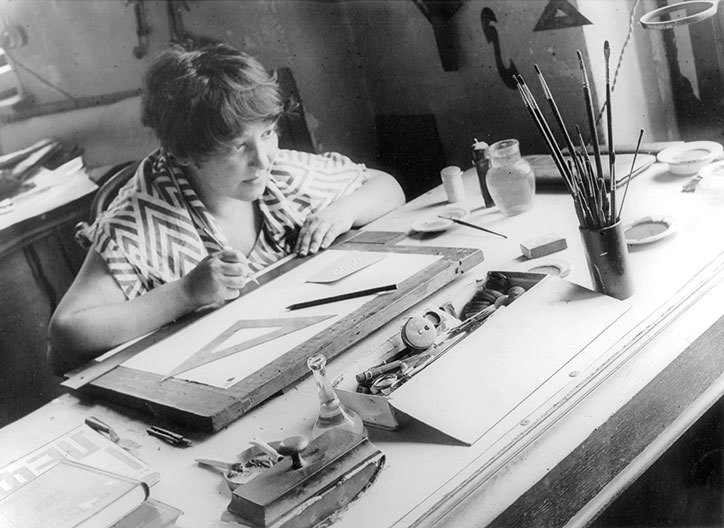

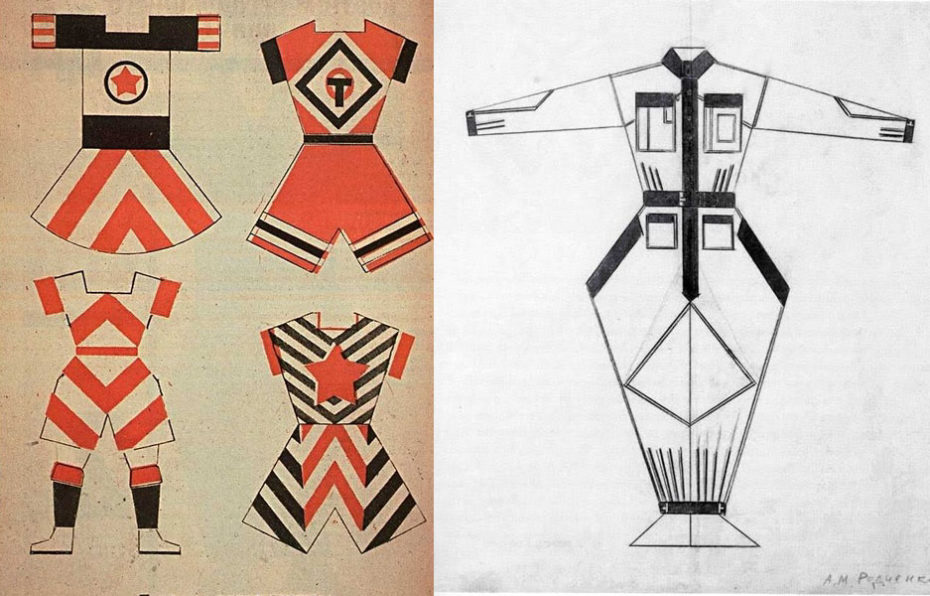

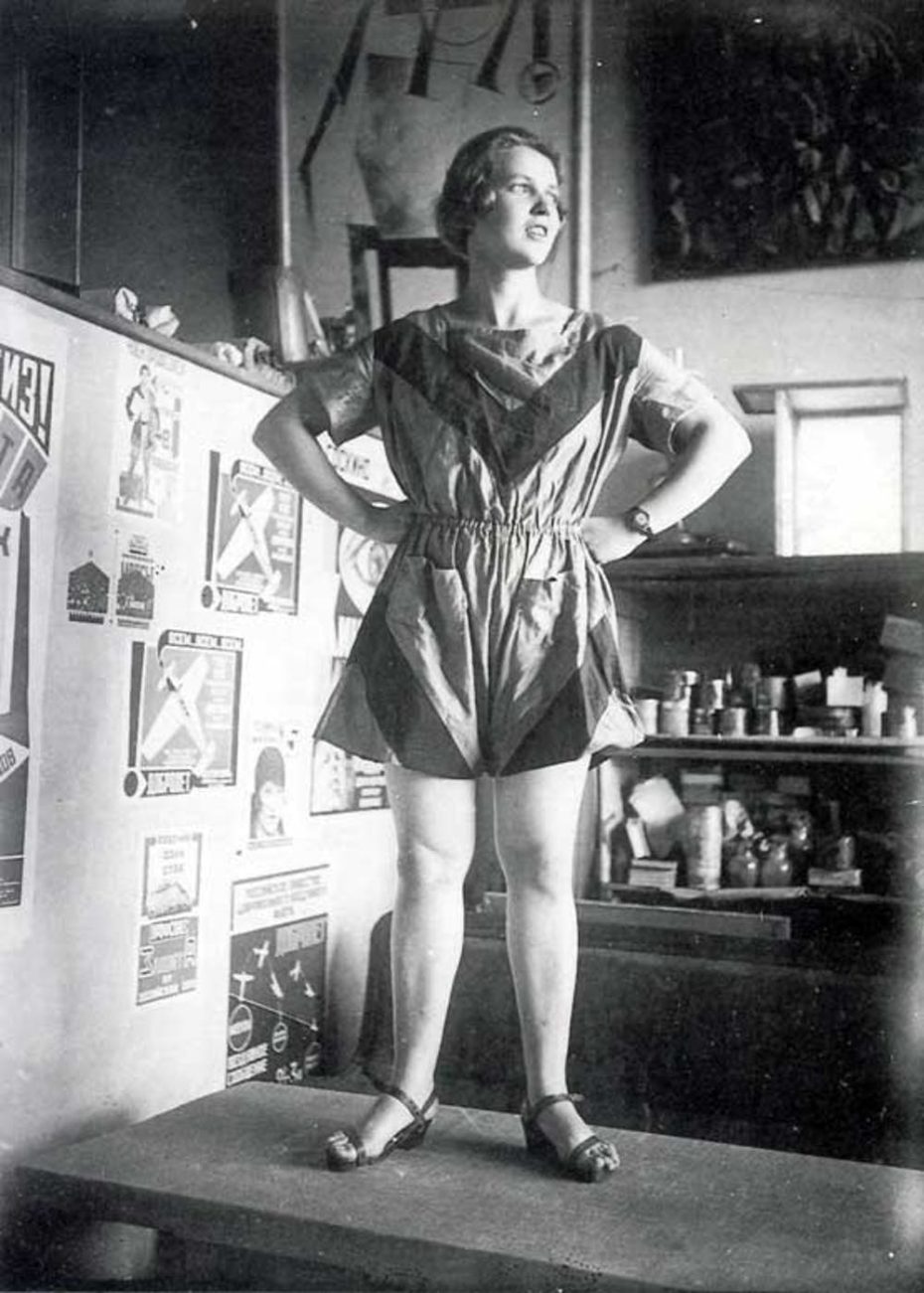

It definitely wasn’t cutting it for women like Varvara Stepanova and Liubov Popova, whose work in a variety of mediums – and in this case – fashion, signalled a creative stirring in the shadows.

Stepanova’s whole outlook on clothing was especially fresh. The artist and designer had already showcased her works at the State Exhibitions, but decided to hone-in on designing for the theatre, where she felt her design philosophy would have a broader reach: what we wear shouldn’t indicate wealth, but equality.

Functionality, a blurring of gender lines and class distinctions were all present in her collections, which often favoured comfy and graphic jumpsuits, and dresses in affordable fabrics.

There was a mounting urge for something bright, bold – something different – and Stalin decided not to ignore it.

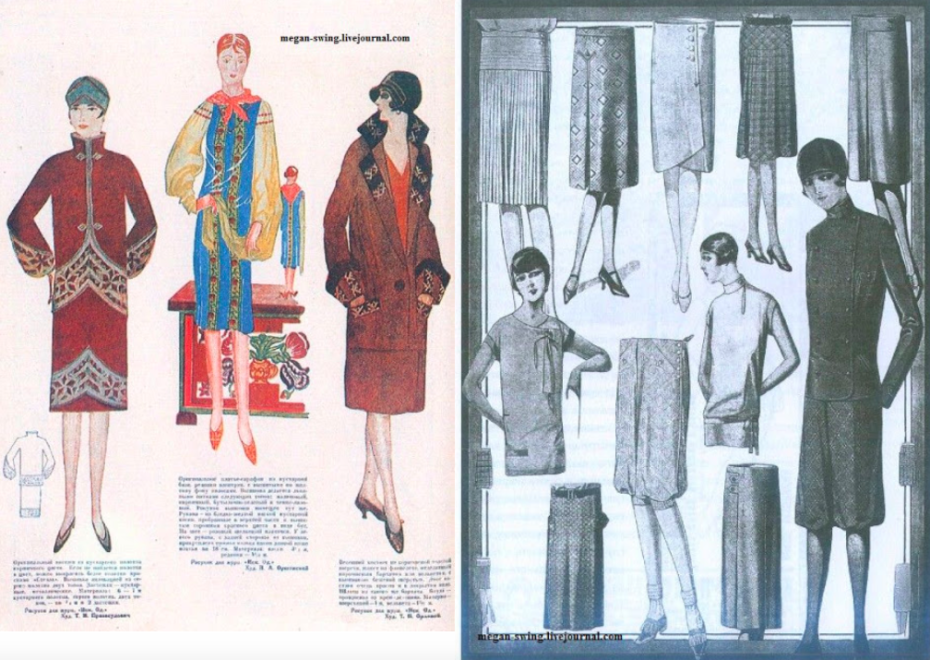

Instead, he decided to one-up the rest of the world with the creation of Dom Modelei, literally, “House of Prototypes” on the fashionable street of Kuznetsky Most in Moscow. Patterns showing chic drop-waists with traditionally Russian-inspired elements (i.e. floral patterns, tassels) started circulating in the 1920s.

A team of mainly pre-revolutionary designers was brought in to make clothing that spoke to two conflicting realities: the anti-aristocratic order of the day, and the extravagance that more privileged folks expected; specifically, the families of businessmen given leeway by Lenin to dabble in private trade. They were known as “NEPmen”, Russia’s last capitalists in the young Soviet Union, people who took advantage of the opportunities for private trade while the communist government turned a blind eye. As time went on, Neps emerged as the first cracks in the patina of communism; in the wake of revolution, their furs, jewels, and more Westernised clothing did more than turn heads, it raised eyebrows. But given the economic benefits that NEPmen provided, Soviet Russia allowed their existence.

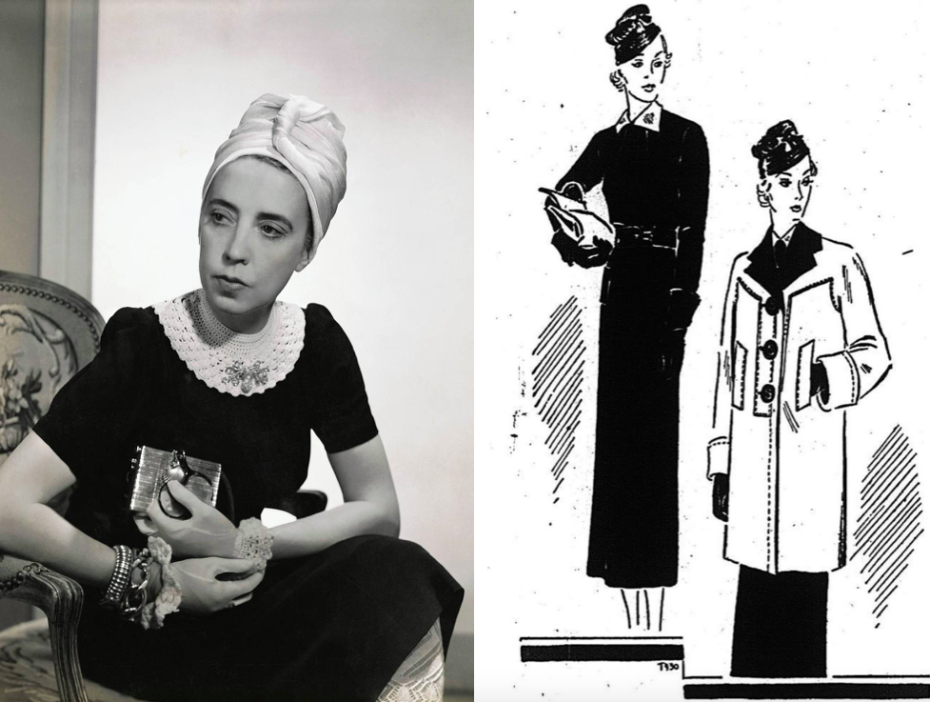

Maybe that’s why Stalin brought in the big-guns for Dom Modelei: Elsa Schiaparelli, the Italian designer who was giving Coco Chanel a run for her money in cutting-edge couture. Schiaparelli gained fame for her boisterous shade of “shocking pink”, and bold silhouettes. Her aesthetic was dazzling, luxurious, and delightfully impractical – the polar opposite of Stalin’s vision for Russia.

Neverthless, she flew to Moscow in 1935 upon invitation where she was floored by the designs. “I was of the opinion that the clothes of the working people should be simple and practical,” she wrote in her autobiography. Instead, she found a collection better suited to a cocktail party.

In a little-known chapter of her career, Elsa Schiapparelli was invited by the communist state to design suitable workwear for the hardworking women of Stalin’s Soviet Russia. We repeat: Schiapparelli, the woman who slapped Dalí’s lobster on a dress for the Duchess of Windsor, and embroidered flirtatious hands on the bosom of a dress, was about to dress the Soviet woman.

Her designs were decidedly more sober, and not many of them made it to production – which was pretty much the case for most of the designs cooked up by Dom Modelei. They rarely met the high standards of the bureaucratic officials – the nomenklatura.

The capsule collection designed by Schiaparelli hardly took fashion risks (it consisted of a red coat, a black dress, and little beret-like hat). But the government said the large pockets encouraged pick-pocketing, and it was given the chop.

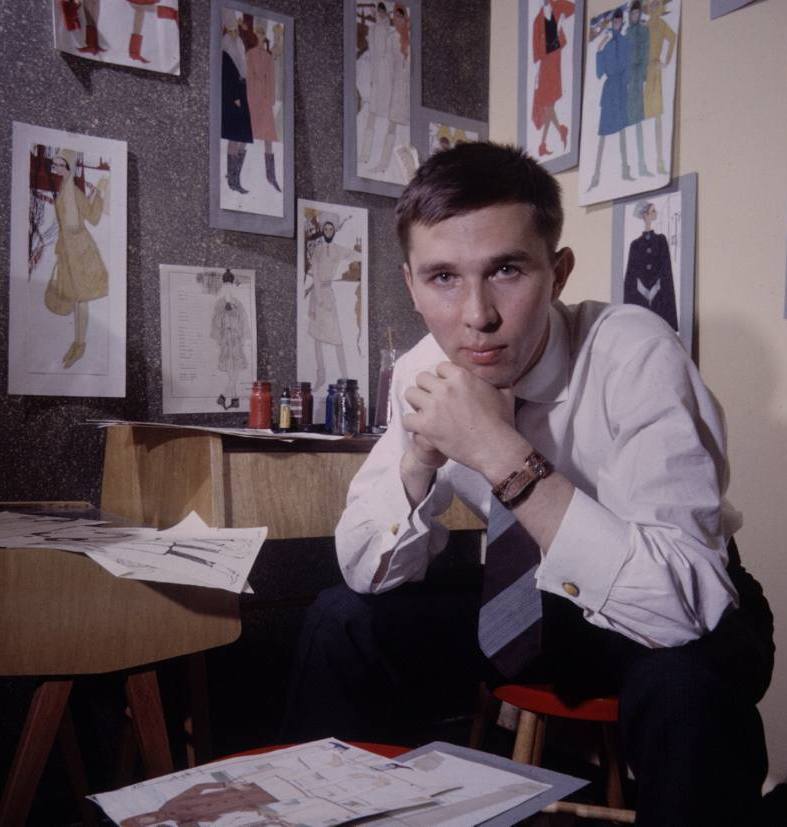

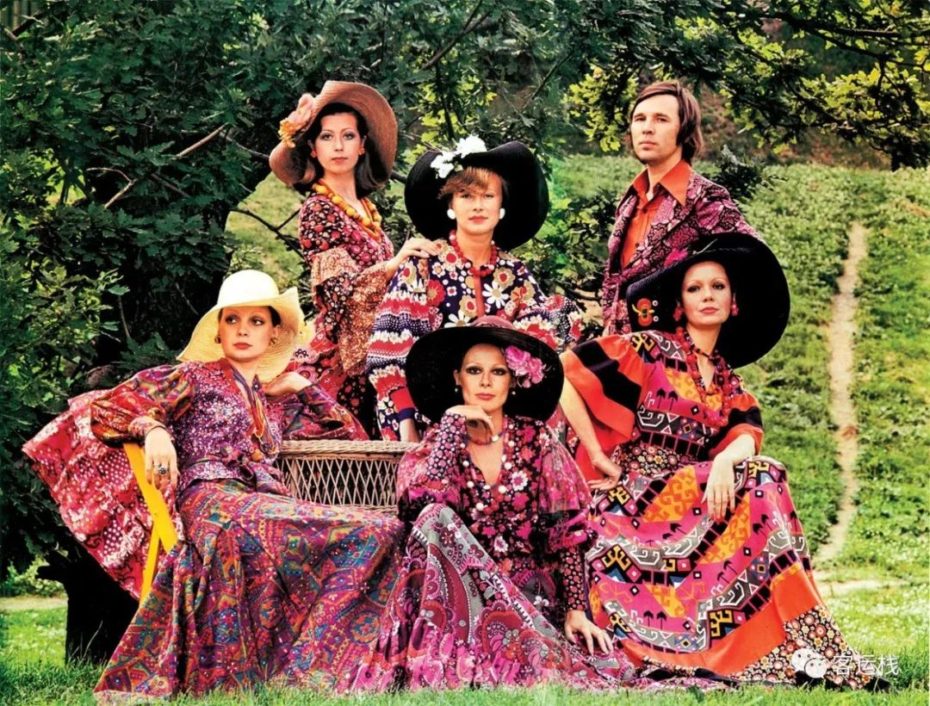

Over the coming decades however, there would be a growing number of talented designers in Eastern Europe and the USSR. Žuži Jelinek’s work had a tremendous influence, while Slava Zaitsev, who was compared to France’s greatest talents and actually called, “The Red Dior,” would be appointed as the creative director of Dom Modelei.

The law at the time forbade him to sell his clothes outside of the USSR and Czechoslovakia, but today he is considered Russia’s most legendary designer.

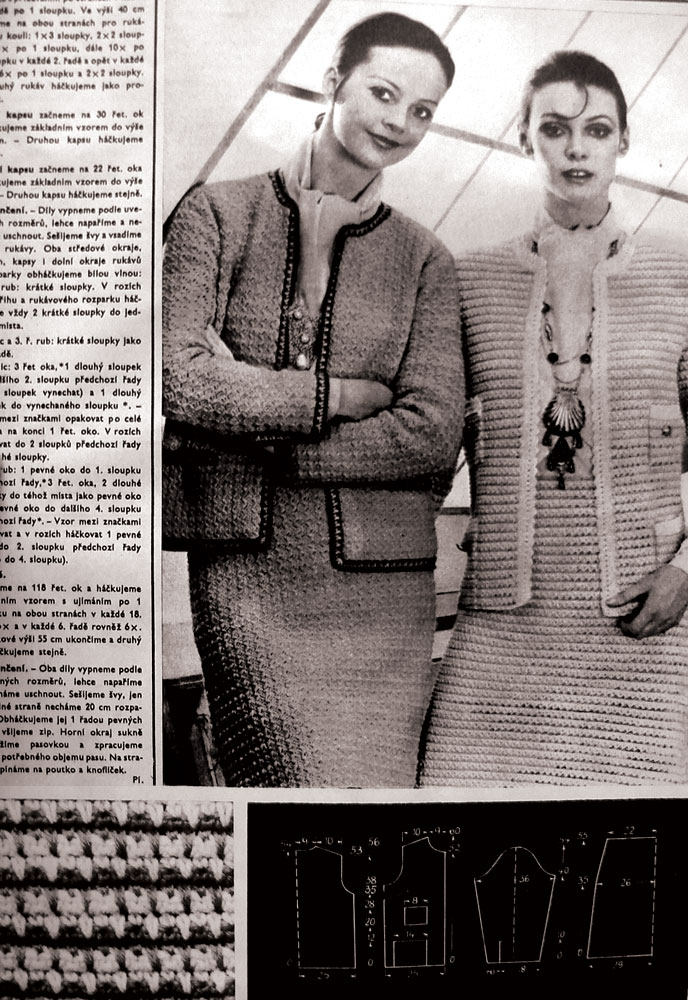

Interestingly enough, as Djurdja Bartlett explains in her book Fashion East, it was Coco Chanel who came out on top in the USSR. In a manner of speaking – the designer never made clothes for Dom Modelei, but rip-offs of her designs were the most realistic models for Soviet production. Particularly after WWII, it became easier for women to find Westernised knitting-patterns in Soviet fashion magazines, mimicking them to their hearts’ content.

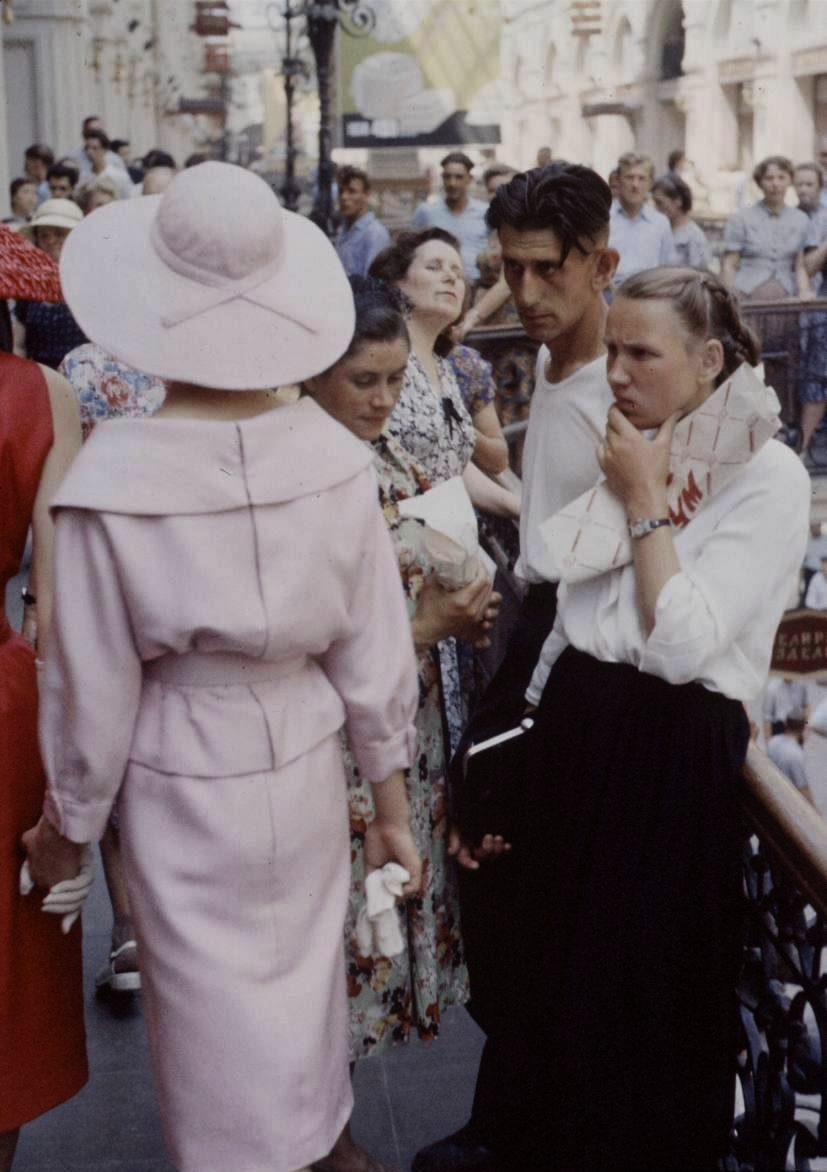

In the end, even Dior was allowed in to Russia in 1959 to show his collections for the first time in history. The fashion show took place in the House of Culture for the he important members of the Communist party and the Soviet elite (oh, the irony).

Afterwards, some of the French models were invited to swan through the streets of Moscow and into GUM, the USSR’s premier department store, to allow “the people” to see the clothes. Most Russian women had only seen very simple clothing produced domestically by state-run fashion houses. The designs were met with mixed reviews…

When all is said and done, we’re left with the reminder that the fashion industry, however superficial it can seem at times, yields a remarkable power to cross party lines – even iron curtains.