One of my favourite things about Eadweard Muybridge, the man who gave us the moving image, aside from the vast array of exotic spellings he adopted for his birth name (Edward Muggeridge), is the idea of him travelling around the American wild west in a 19th century carriage which he converted into his very own portable darkroom. He also got away with murdering his wife’s lover, but admittedly, that’s not one of my favourite things about Eadweard. When you look into Muybridge, his own story turns out to be just as intriguing as the one behind all those naked photographs he took to invent motion picture photography in the 19th century. Before his exhaustive study of animal and human movement, before he created the world’s first commercial movie theatre, he led the kind of fascinating, eccentric and dangerous life that would seduce any Hollywood screenwriter. Whether you’ve seen his captivating work but never heard his story, or you’re discovering Eadweard Muybridge with fresh eyes today, you’re in for a peculiar treat…

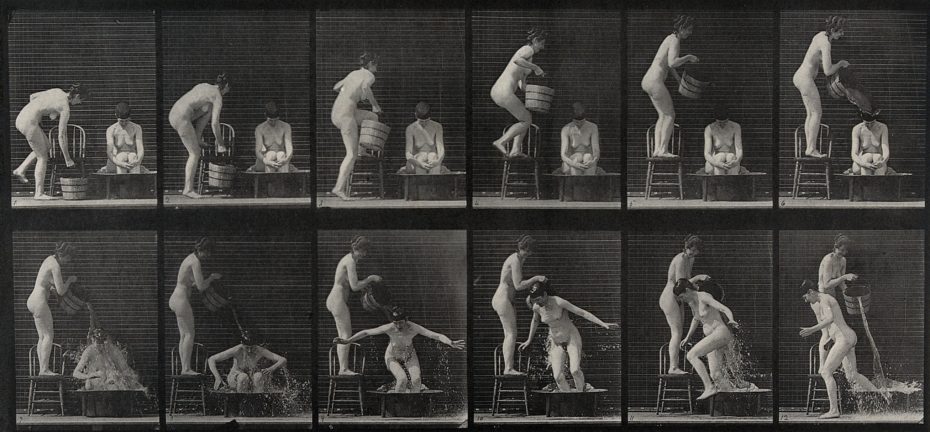

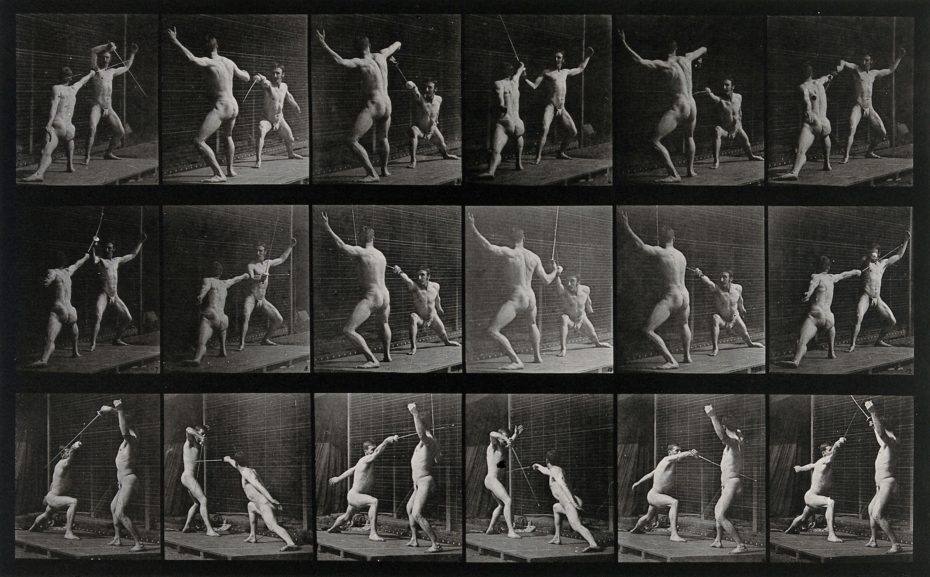

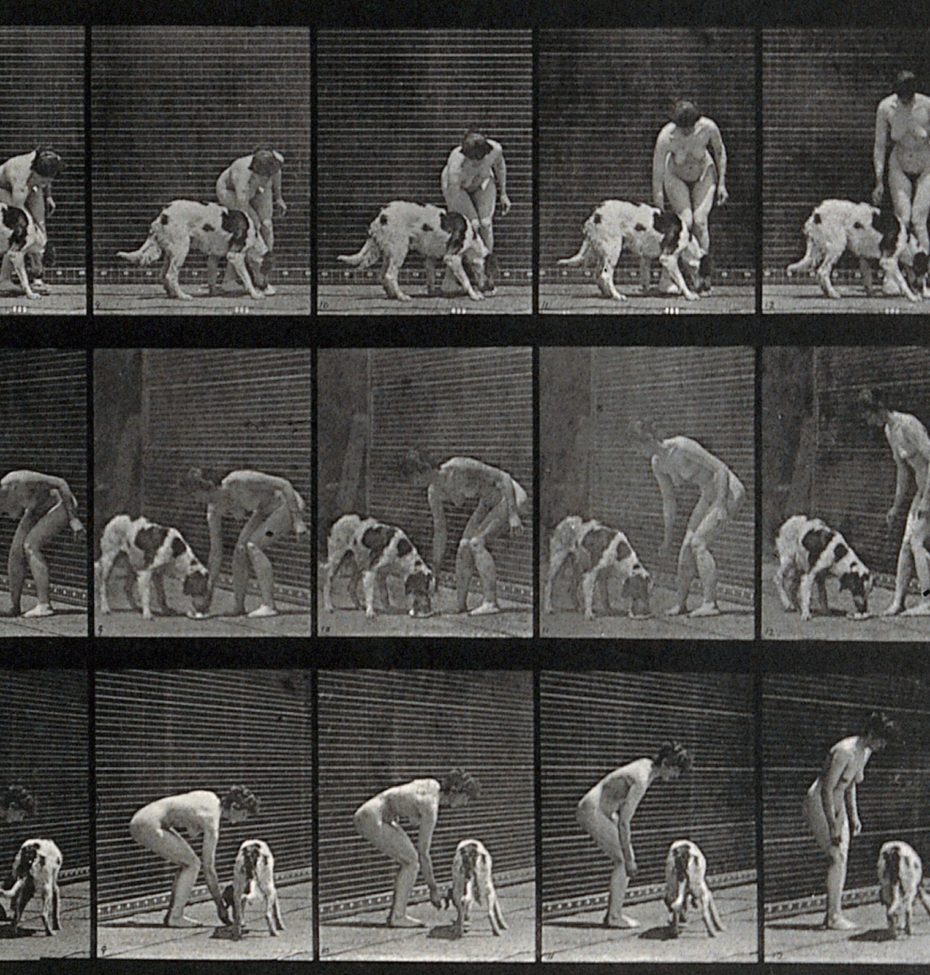

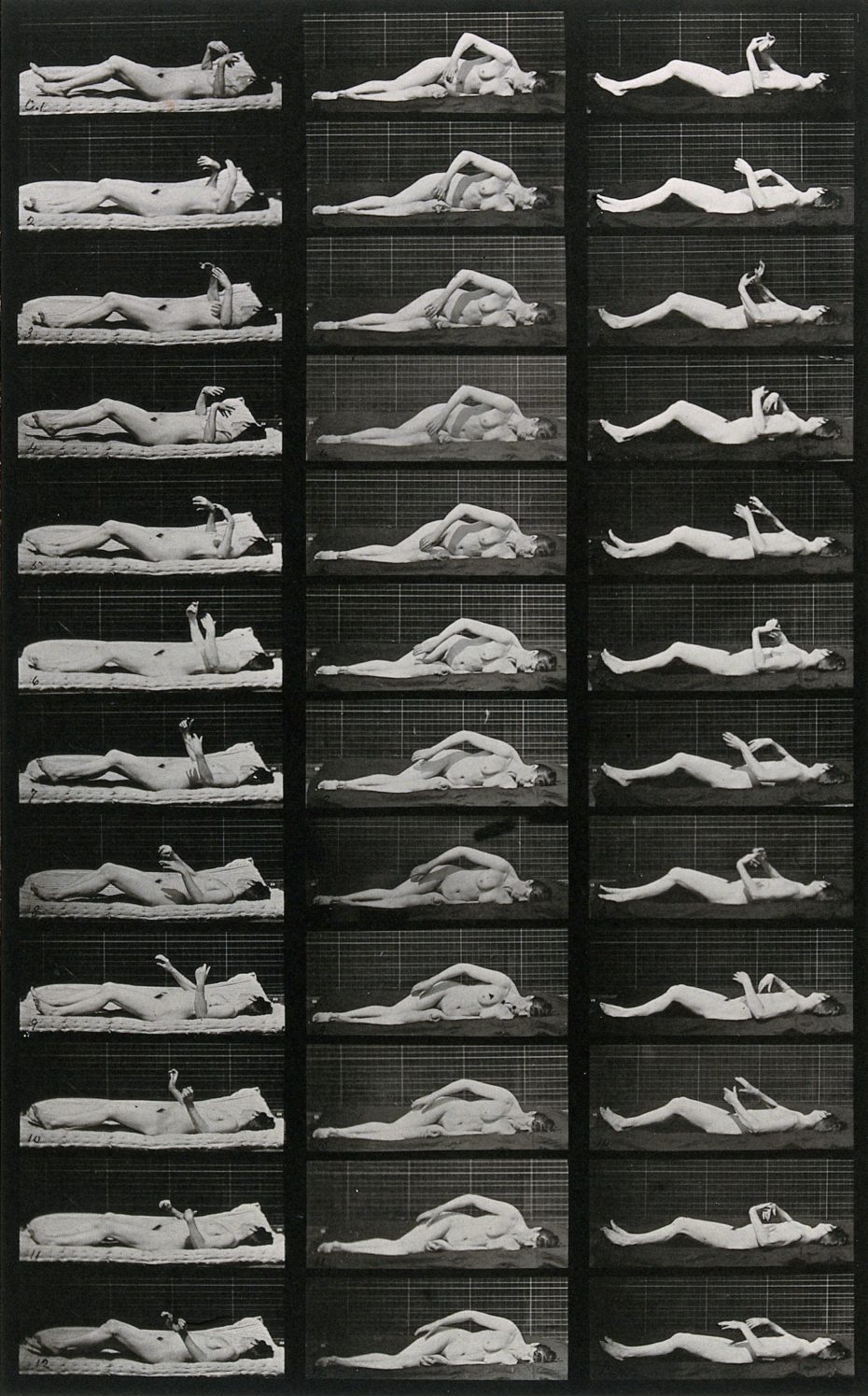

Browsing through the various archives that collectively hold over 100,000 images produced by Muybridge, the first thing you’ll probably wonder is – why did they all have to be so … naked?

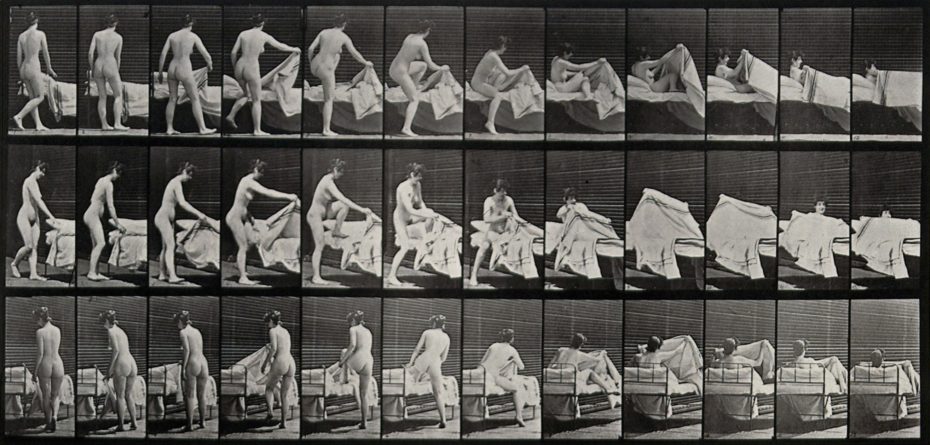

Most of them are innocent enough, ya know, in the name of science. “A woman running”, “a man climbing stairs”. Even Muybridge himself, who was very proud of his ageing athletic body, posed nude for the camera in several of the collotypes. But then things get a little weirder, and the captions start sounding like a fetish menu…

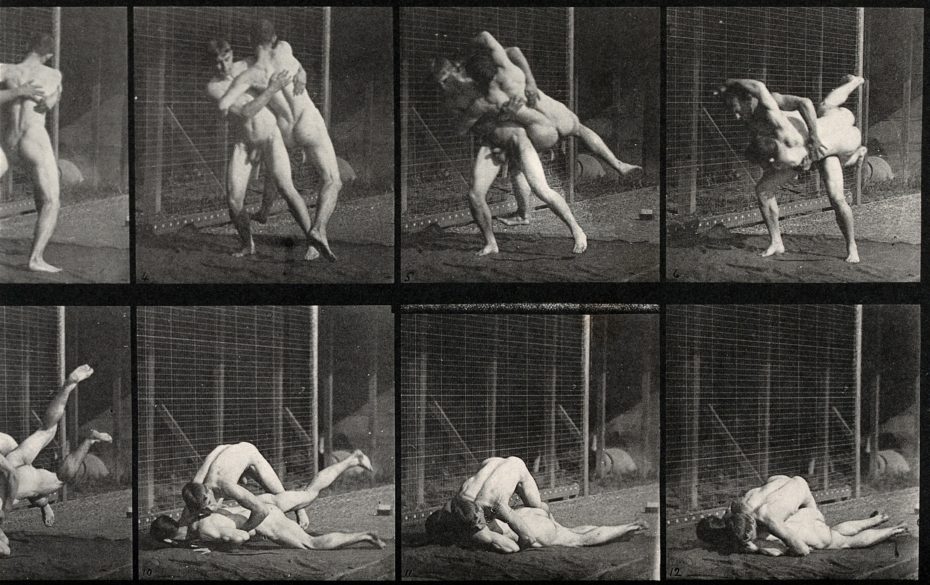

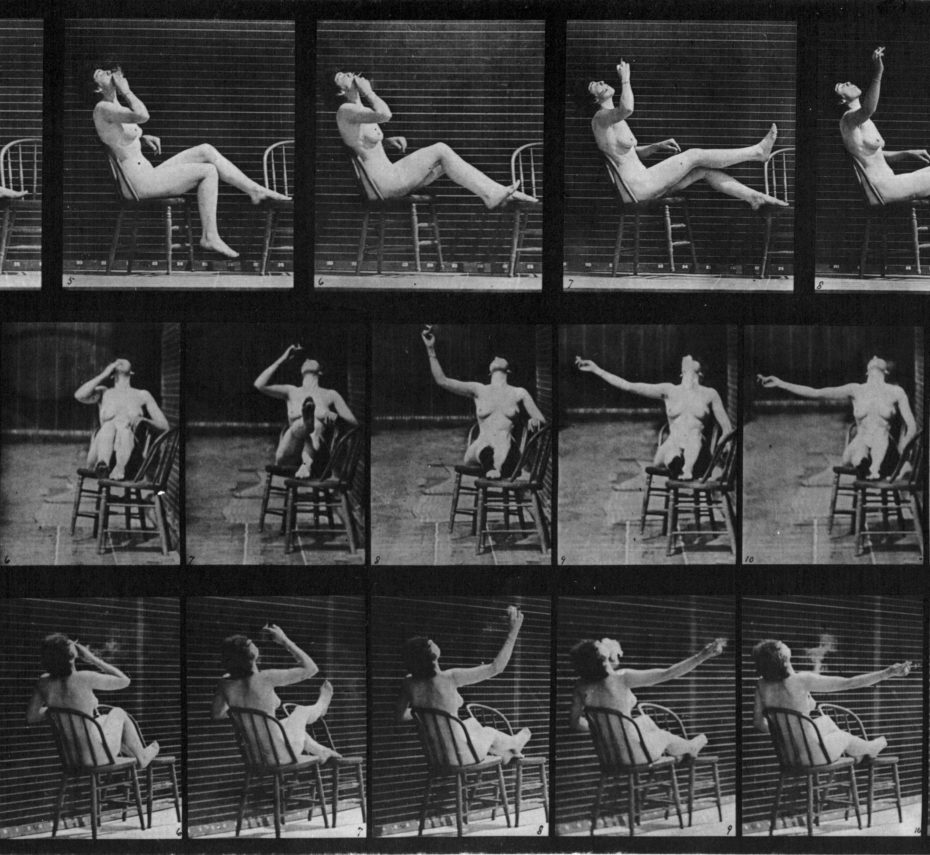

“A naked woman feeding a dog”, “a naked man bowling”, “an obese woman getting off the ground”, “a naked woman on the ground with artificially induced convulsions”, “two women kissing”. It’s all there, in black and white – and in the buff.

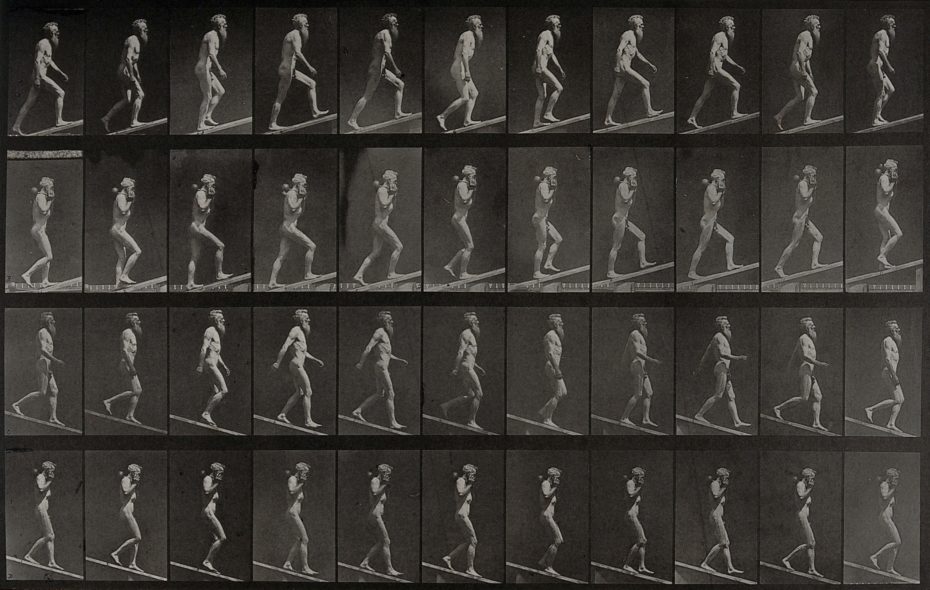

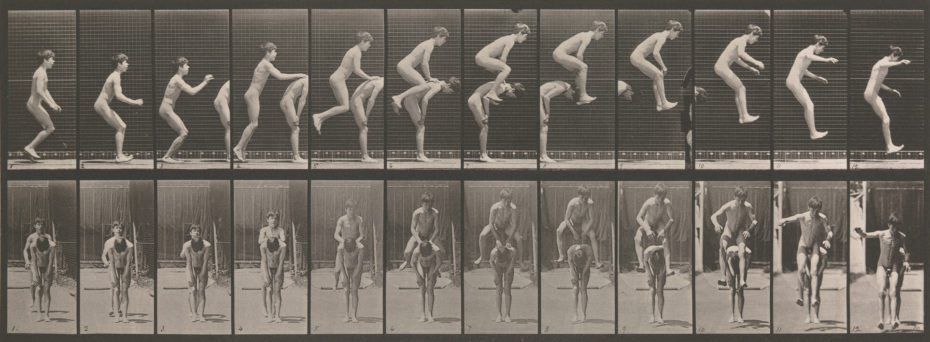

For the unsuspecting soul who stumbles upon Muybridge’s archives without any backstory or context, one might find the collection somewhat bewildering. And little would most people know, that these strange old naked pics were stills from the world’s first moving images, capturing what the human eye could not distinguish as separate movements of animals and humans in motion.

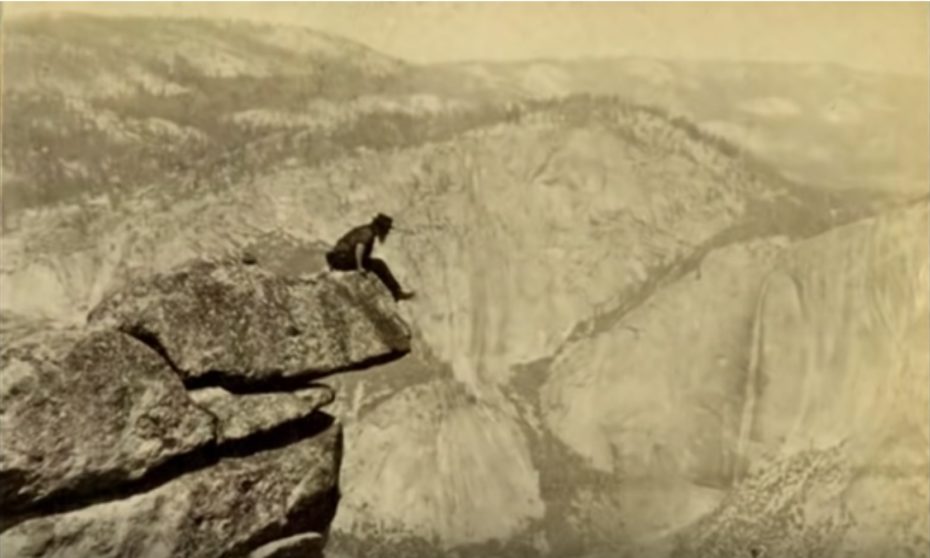

Eadweard Muybridge emigrated from England to America at the age of 20 and became a successful bookseller in San Francisco during the height of the California Gold Rush. He travelled frequently to acquire antiquarian books, but in 1860, was involved in a violent runaway stagecoach crash and ejected from the vehicle, hitting a rock head first. He spent years recovering; suffering from double vision, confusion, and began having emotional, eccentric outbursts. But he also began exploring his own creativity, free from social inhibitions, and it was during this time that he learned to photograph using the wet-plate collodion process. He made his mark as a landscape photographer in the Yosemite Valley, travelling in his carriage that doubled as a darkroom and taking daring shots thousands of feet high above the valleys.

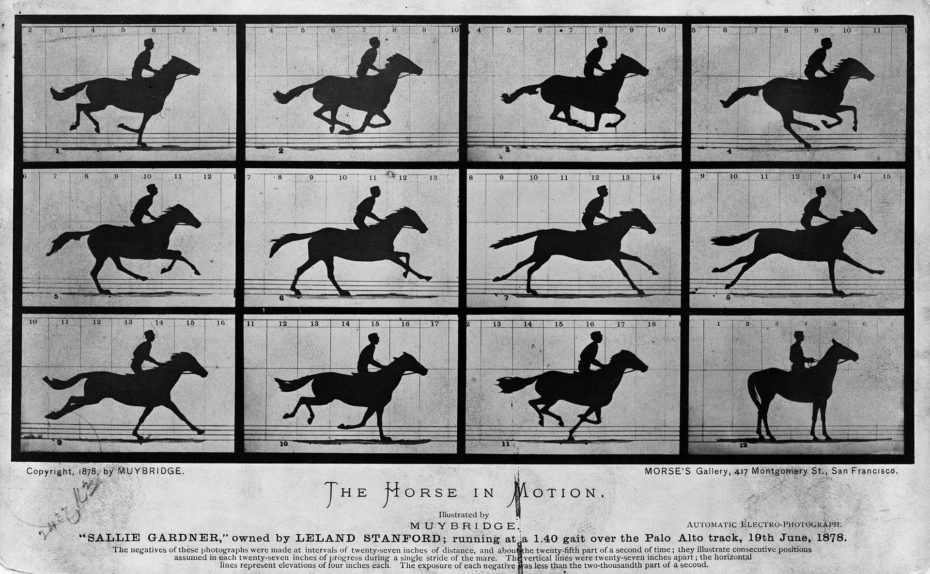

The US government sent him to photograph the newly acquired state of Alaska and then up and down the West coast to document the country’s lighthouses. Muybridge’s work caught the eye of former California governor, Leland Stanford, a wealthy race-horse owner who had taken an interest in studying animal movement, which was something of a hot topic of the day. For centuries, painters had depicted horses in flight with their feet outstretched like a rocking horse. Stanford made a bet that all of a horses hooves leave the ground when it gallops. He placed the bet at $25,000 and hired Muybridge to help him prove it. In the process, Muybridge would invent the motion picture on a farm that would become Stanford University.

Using twenty four glass plate cameras, the shutters were triggered by trip-wire on the track. His study proved that Leland’s controversial theory was right, and contrary to what painters had depicted, a horse’s feet in gallop are not outstretched, but bunched together under the belly. Eadweard’s work was revolutionary, and his discovery caused considerable controversy.

While Muybridge was working on these experiments, he was a busy man who didn’t get back to his young wife Flora very often. He got wind of her affair with a soldier who may or may not have fathered Flora’s newborn son. Muybridge personally tracked down her lover and upon finding him said to him “Good evening, Major, my name is Muybridge and here’s the answer to the letter you sent my wife.” He shot the soldier point-blank and was taken to jail without protest that same night.

He was tried for murder, pleading insanity due to his stagecoach injury earlier in life, but undercut his own case several times during the trial by reaffirming his actions were deliberate. Stanford paid for a strong defence team and Muybridge was ultimately acquitted on the grounds of “justifiable homicide”.

The photographer continued his work for Stanford (as a single man) but the two soon fell out when the horseman published a book The Horse in Motion using all of Muybridge’s research but failing to credit him at all. After a failed attempt to sue Stanford for credit, Eadweard accepted an offer from the University of Pennsylvania where he began working obsessively on the study of motion, particularly human motion, using multiple cameras to produce separate images.

He would project the images using a machine he had invented called the “zoopraxiscope”, pre-dating the flexible perforated film strip as the first movie projector that would pave the way for cinematography. In 1893, he used the zoopraxiscope to show his moving pictures to a paying public, rendering the exposition hall the first commercial movie theatre in history.

Now back to those nudes. “I strip away the clothes not to see the flesh, but to better see the motion,” Muybridge told one shocked puritanical donor at the University of Pennsylvannia. “If I were able, I’d strip away the flesh as well in order to see the muscle, then strip the muscle to see the bone, and I’d even throw away the very skeleton if it could afford me the opportunity to see the unencumbered essence of an action.”

The models we see in Muybridge’s work were not professional models. In fact, he insisted on working only with non-professional local citizens or with university’s students (as well as animals from the Philadelphia Zoo). Their naked bodies were photographed in an array of conventional and unconventional scenarios against a grid for scientific accuracy in an outdoor enclosed studio.

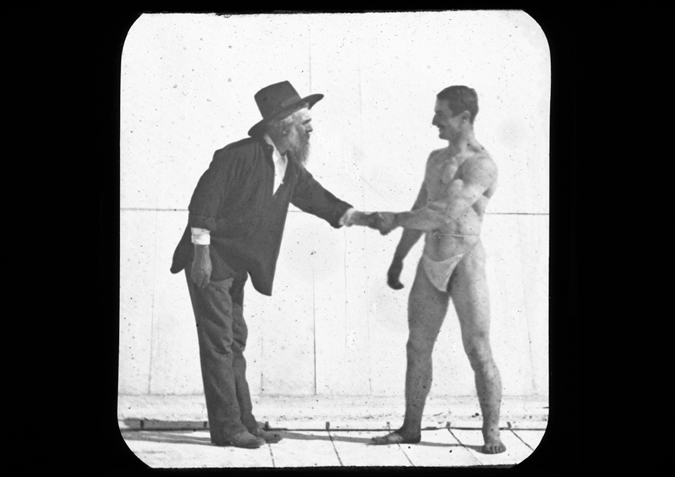

“It might be easy to deem outrageous the suggestion that Muybridge was aware of any overt sexual elements in his experiments,” writes Anthony Slide in essays on undocumented areas of silent film. “Muybridge got a kick out of his nudes; the male nudes were perhaps more appealing to his friend and “supervisor” the great American painter Thomas Eakins.”

Eakins was serving on Muybridge’s supervisory committee at the University of Pennsylvania and had his own philosophy: to paint you nudes, you must be willing to pose nude. Rumours circulated around town that Eakins had started a relationship with one of the men with whom he posed for his friend’s work.

“Whatever went on at the University of Pennsylvania in the classes of Muybridge and Eakins,” says Slide, “One thing is for certain. Everyone– students and professors– must have had a good time.”

Discover the work of Eedward Muybridge, the grandfather of motion pictures in the Wellcome Library Archives.