Creative inspiration lives on a carrousel. Meaning, bygone trends and inventions always rear their heads at another point in history, finding relevancy for a new generation — and, yes, usually the generation in question is millennials, who’ve successfully resurrected a love for handlebar moustaches, Bukowski and bespoke taxidermy. Today, we’re making a case for the most recent acquisition to the current cool-kid aesthetic on your Instagram explore feed: René Magritte, Surrealist painter and premature hipster extraordinaire…

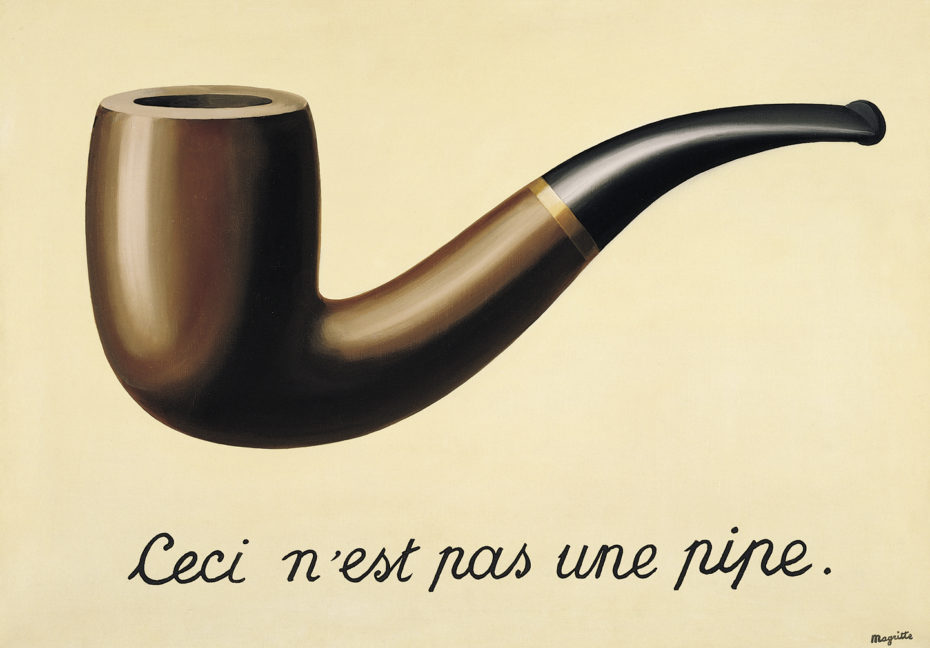

You know Magritte, even if you don’t think you do. His work has reached iconic status, gracing postcards and merch like his contemporaries Picasso, Dali, Matisse (and so, so many others). In fact, some avid MessyNessy readers may recognise his iconic 1928 painting with phrase, “Ceci n’est pas une pipe” (or “This is not a pipe.” The painting’s actual title is “The Treachery of Images”) revisited on our official t-shirt:

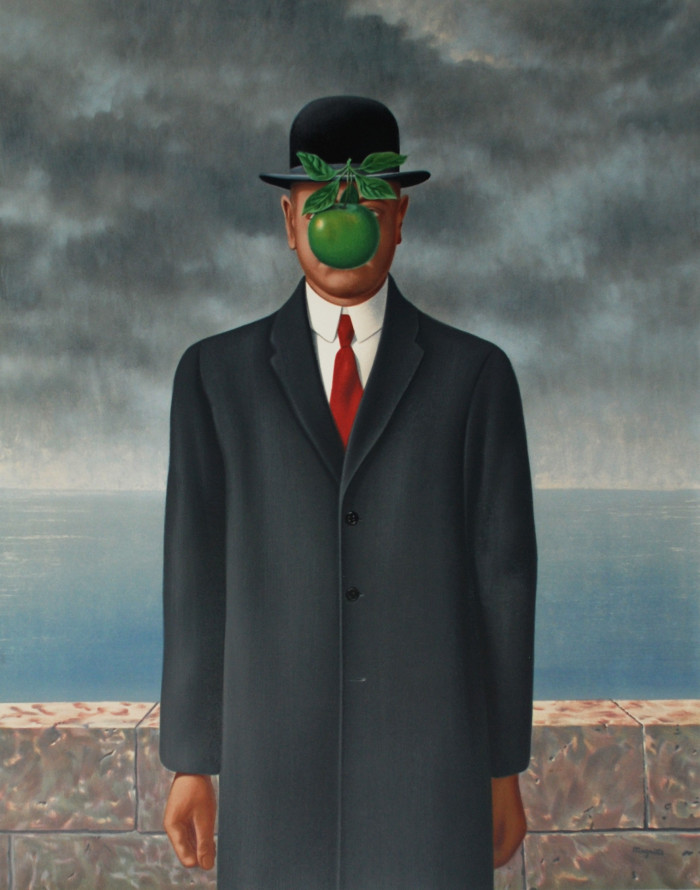

And if you don’t know the pipe pic, chances are you’ve seen someone dressed up as the “Son of Man” apple guy at a costume party, or had his deliciously flat, bright blue skies engrained in your brain…

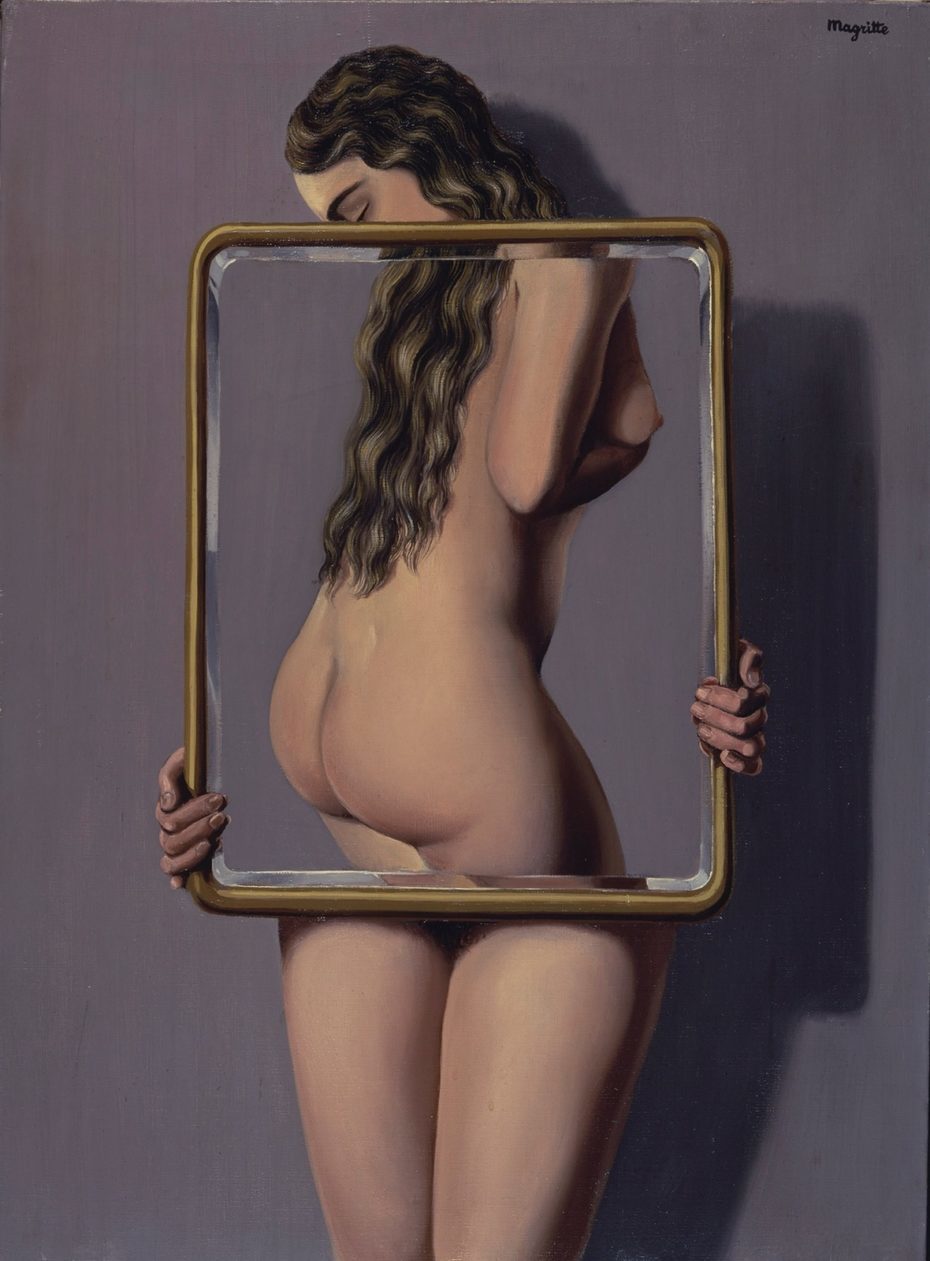

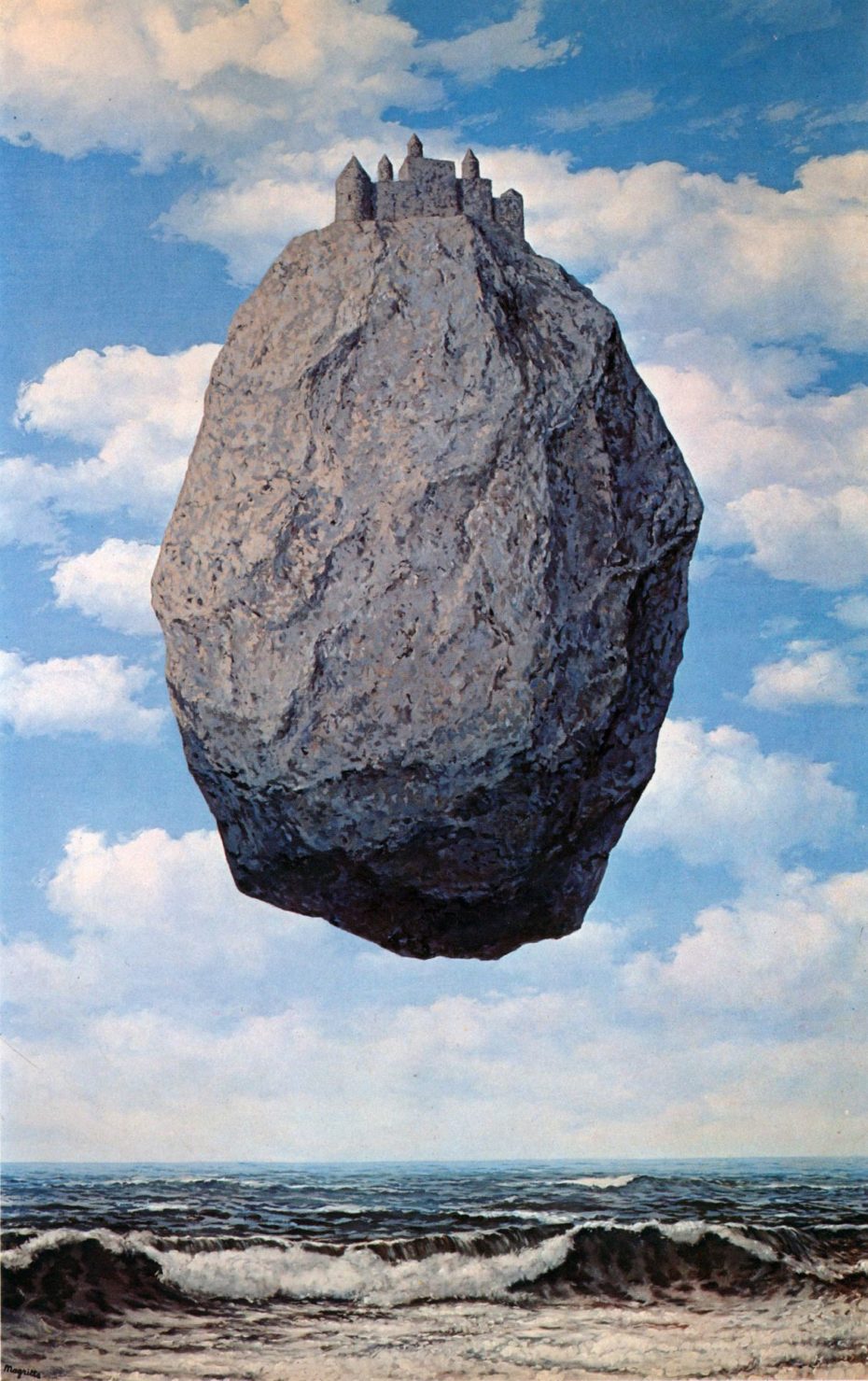

Magritte’s work was crisp, and witty. It was Surrealist to the bone, but with an aesthetic that leaned more towards the perfectionist eye of Wes Anderson than the erratic, melting of clocks of Dali. Often, he found a way to juxtapose banal objects or phenomena that felt dreamy, and a little unsettling, and with an air of detachment through his very sober brushstrokes (no spasmodic Van Gogh skies here).

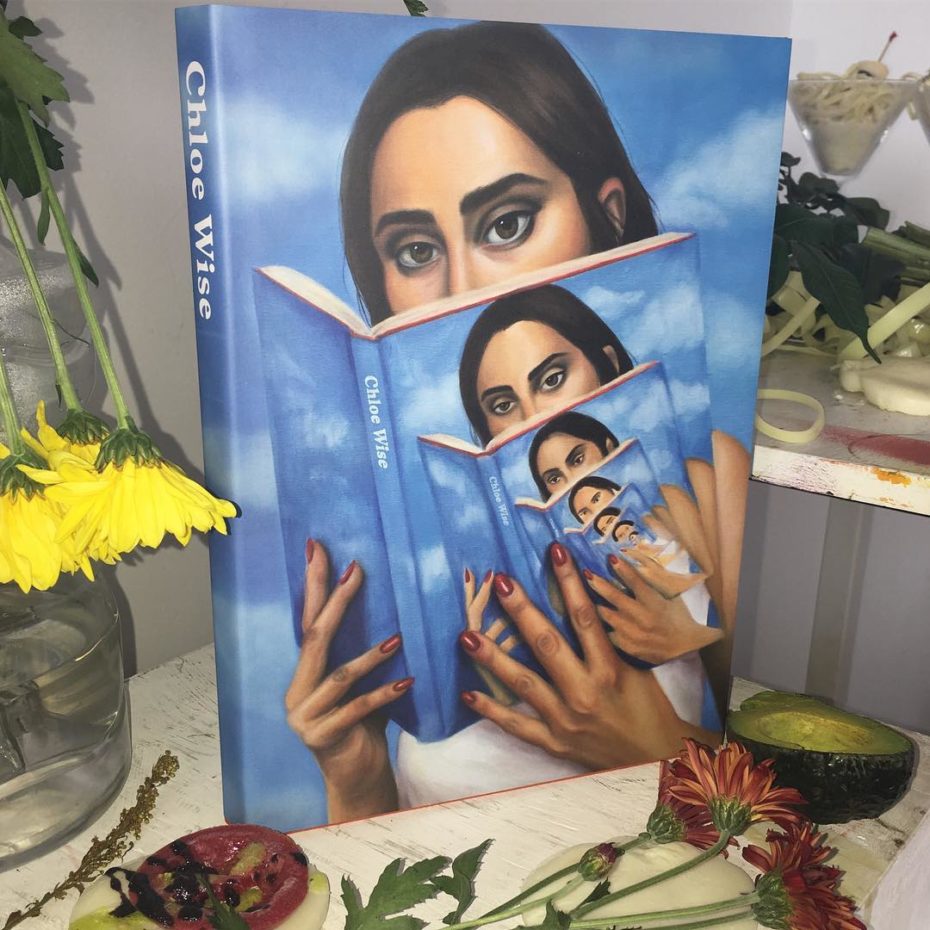

It’s an aesthetic not unlike the work of current It-girl and painter Chloe Wise, whose still life paintings make more than a slight nod to his style in not only her technical style, but subject matter; like Magritte, Wise hones in on everyday objects like food and clothing, often in portraits of those close to her as an exploration of body image and identity. Oh yeah, she even has a Magritte background on her iPhone.

Wise isn’t alone. Big names in fashion like Gucci, Mulberry, and Opening Ceremony all owe a debt to Magritte for some of their collections in the last few years. The influence varies of course, and for some comes out only in glimmering moments via a surreal summer ’18 ad campaign (Gucci) or a dangling, pearly eyeball à la Magritte’s Scheherazade (Mulberry). Opening Ceremony even worked with the late painter’s estate to create a capsule collection in 2014.

One of MessyNessy’s favourite Parisian fashion brands, Amélie Pichard, also just launched a micro-campaign for their vegan crocodile bags with stickers reading, “ceci n’est pas un it-bag”:

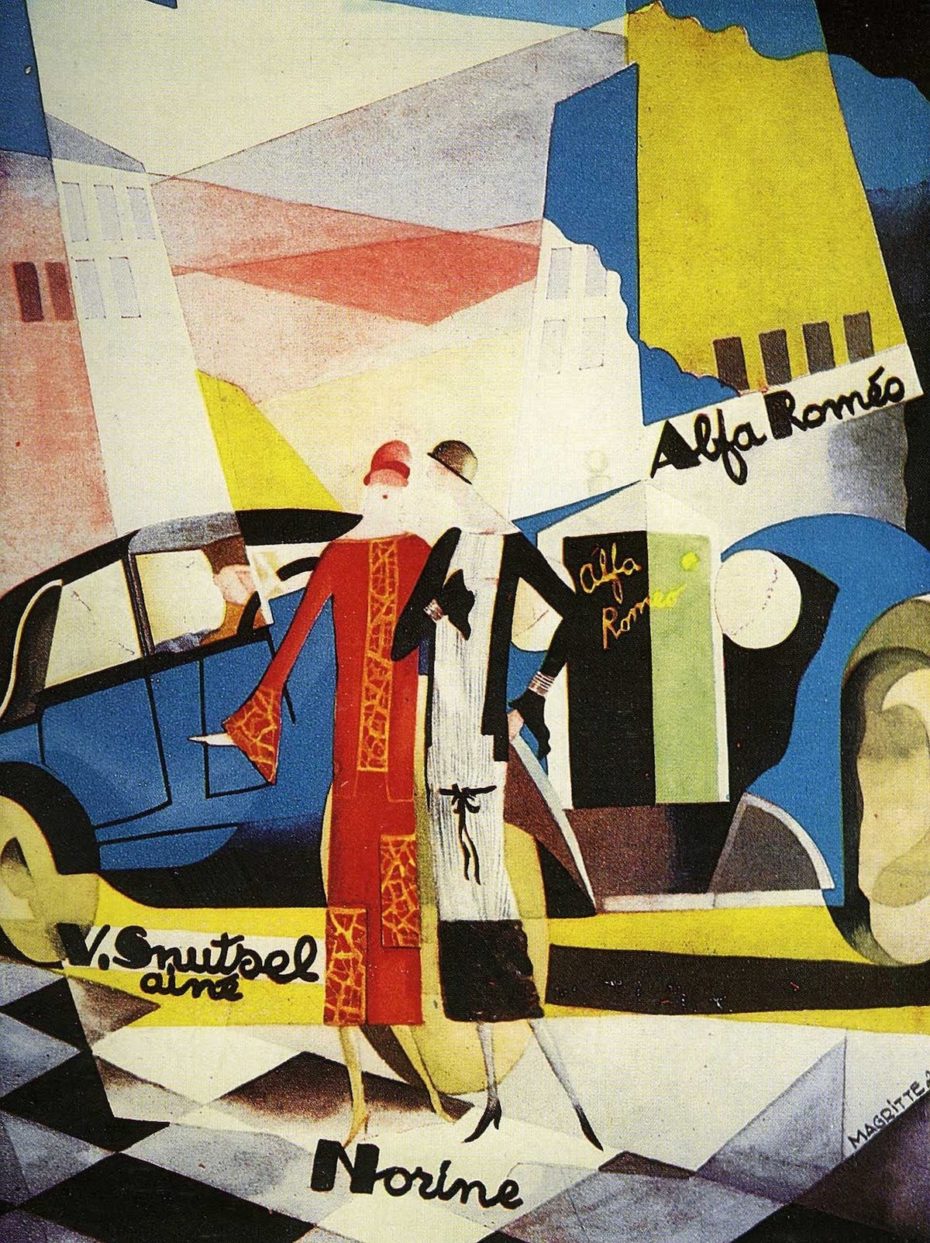

Magritte’s influence feels so close to us today, that it’s hard to believe he was born in Belgium in 1898 (he was the son of a textile merchant and hatter — which may partially explain the obsession with bowlers). Like Dali, Magritte depended on commercial and graphic design to pay the bills. Art brought fame, but it didn’t bring home serious bacon until the last decade or two of his life. So perhaps there’s something to be said about having one foot in the mainstream, and one foot in the avante-garde to solidify one’s artistic legacy; Dali, Picasso, Warhol — all the artists whose works have endured on a far-reaching scale weren’t snobs when it came to applying their serious talent to ostensibly frivolous projects. Like Dali’s Alka Seltzer commercial, or Magritte’s 1924 Alfa Romeo ad:

In fact, the iconic “Son of Man” apple painting inspired The Beatles’ Apple Records Logo, and Magritte’s artwork ended up on some pretty hip album covers, from Beck-Ola’s 1969 green apple album, to 1975’s Vienne La Pluie by Daniel Balavoine, which used Magritte’s 1958 painting, “Hegel’s Holiday”:

CBS basically stole his 1928 work, “The False Mirror,” to transform it into the world famous eyeball logo we have today. Apparently, the first draft of the logo looked so much like Magritte’s painting that the artist had to take legal action…

The CBS episode does open-up a discussion on authorship, copyright, and authenticity in the 20th century art world — not that creative theft and forgeries weren’t happening in the Renaissance, but industrialisation and 20th century technologies took it to a whole new level. Andy Warhol actually loved to admit that he was a self-forging artist (many of his Factory friends made his prints), seeing the declaration as a kind of performative statement on consumerism, and the elitism of art buyers. In the 1960s, it seemed batty. Today, it’s the kind of brazenness admired in artists like Banksy, whose made his painting casually self-destruct when sold at auction for $1.4 million a few months ago.

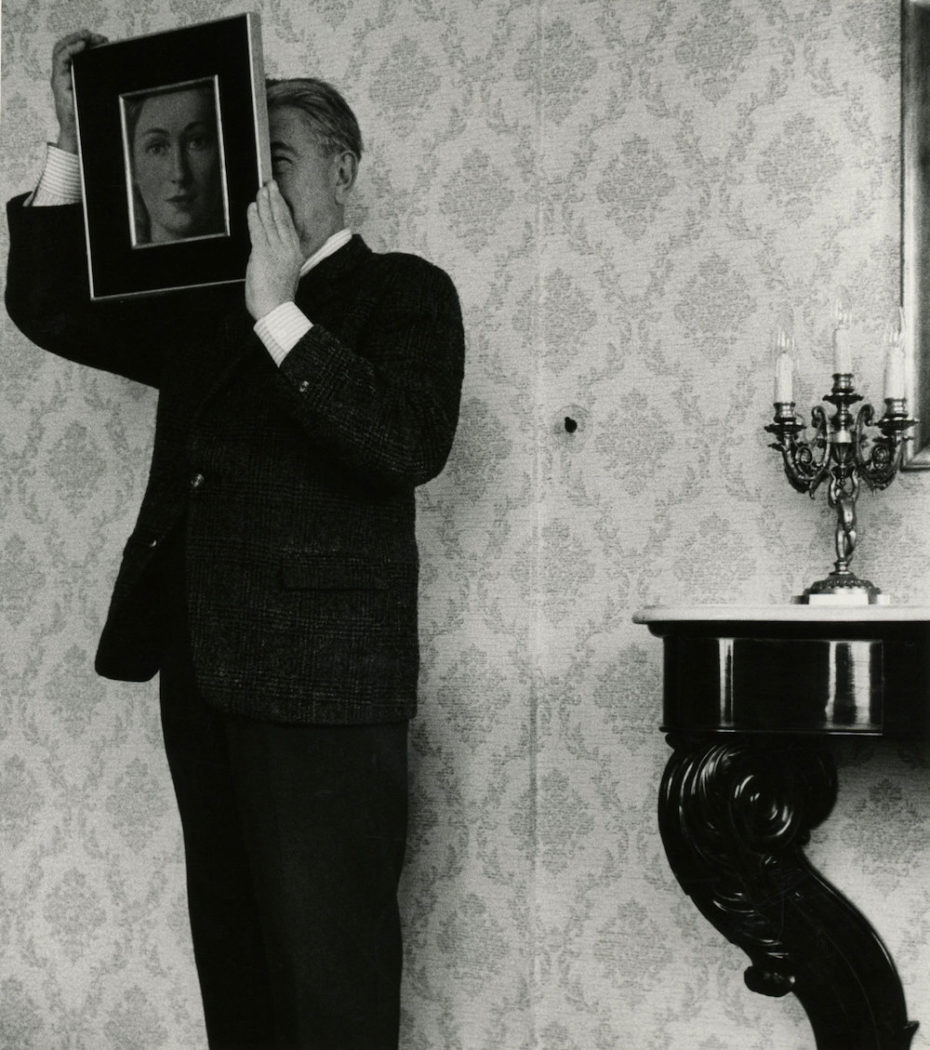

This brings us to what is arguably one of the most fascinating, and controversial aspects of Magritte’s legacy: he was a master forger. Rather than stick with the status quo, he duplicated his own paintings, like “The Flavour of Tears” in clandestine fashion, selling them as one-of-a-kind pieces. It’s uncertain how many of his pieces he may have recreated, but according to his friend Marcel Mariën’s biography, he also forged works by Picasso, Titian, Max Ernst, and Giorgio de Chirico – many of his contemporaries. Not cool, Magritte. (But also, kind of cool.)

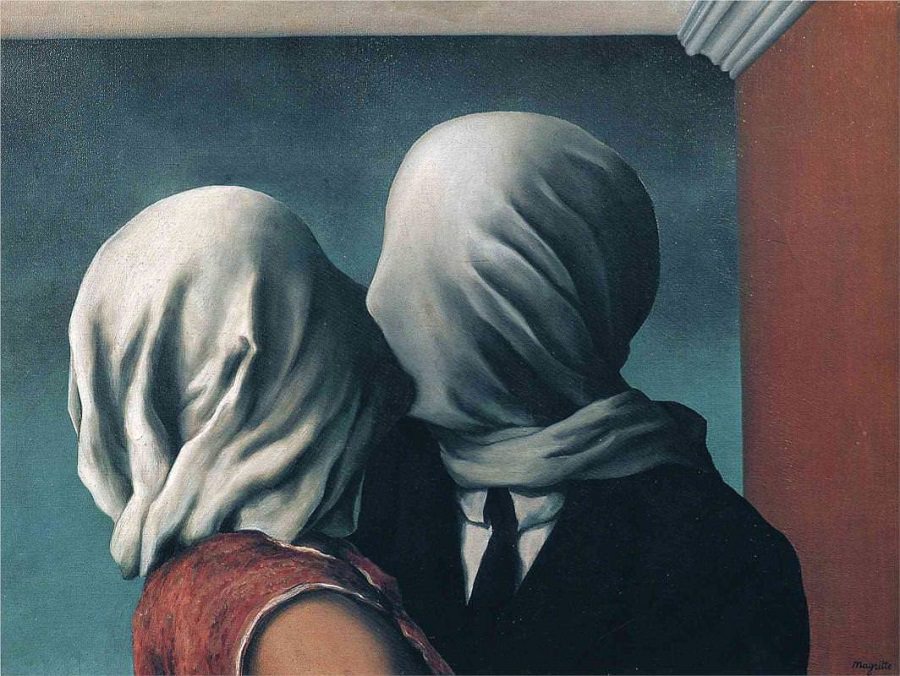

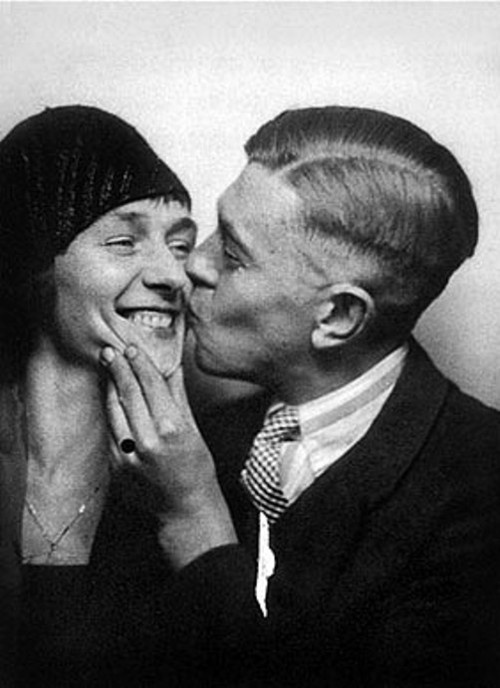

Magritte’s entire life is footnoted with curious little facts in the same way his paintings are — and unapologetically so. The tumultuous story of his muse and wife Georgette, the local Butcher’s daughter, crept into the public’s eye (whether they knew it or not) in paintings like The Lovers, II (1928):

The splashes of millennial pink, on-trend shapes, and facility to fall into designer collections — it’s clear that Magritte’s work has the lifespan and malleability to feel at home in a contemporary context. A lot of that can probably be traced to his talents in advertising, and in crafting images with universal appeal and staying power. But we’d also credit his current coolness to the way he so expertly imbued emotion in his works like The Lovers, II, proving that the most important element of a work isn’t just how its coolness catches our eye, but captures our hearts.