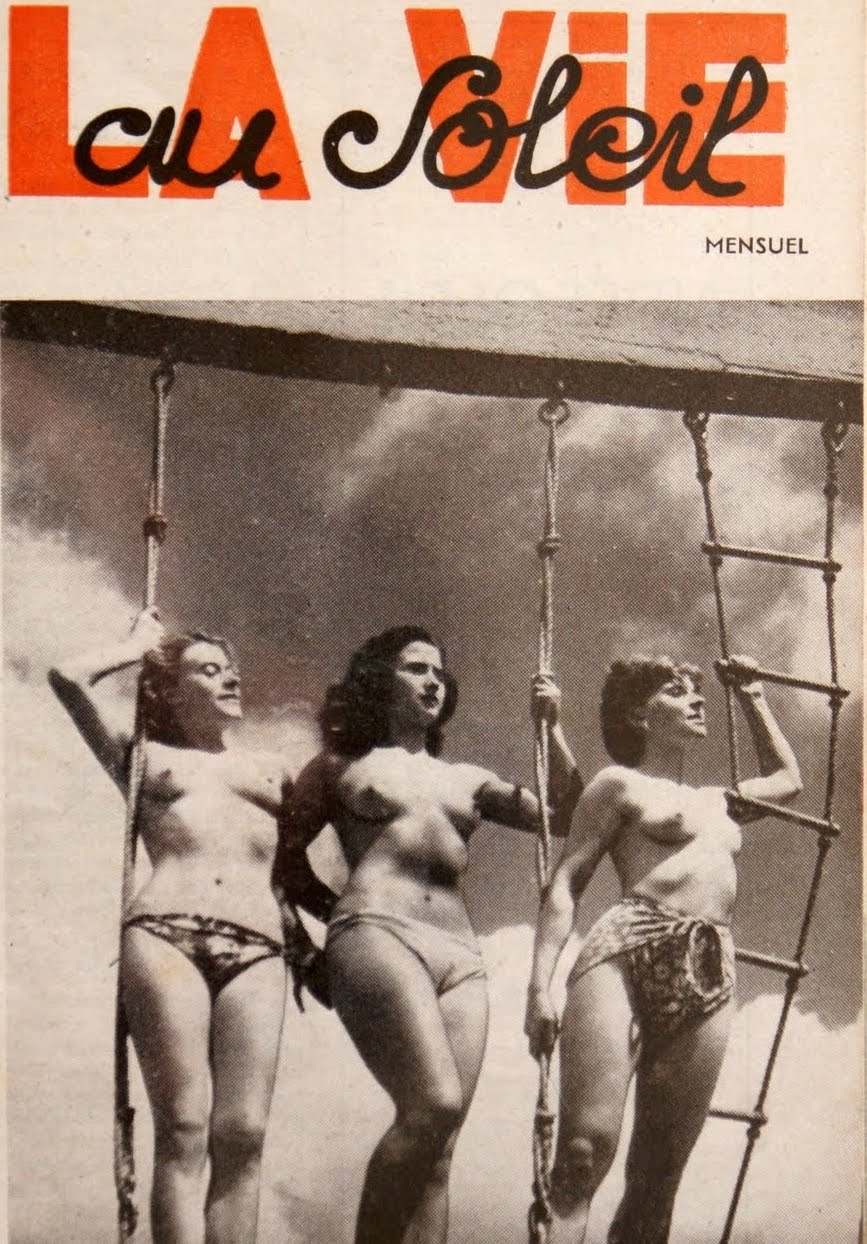

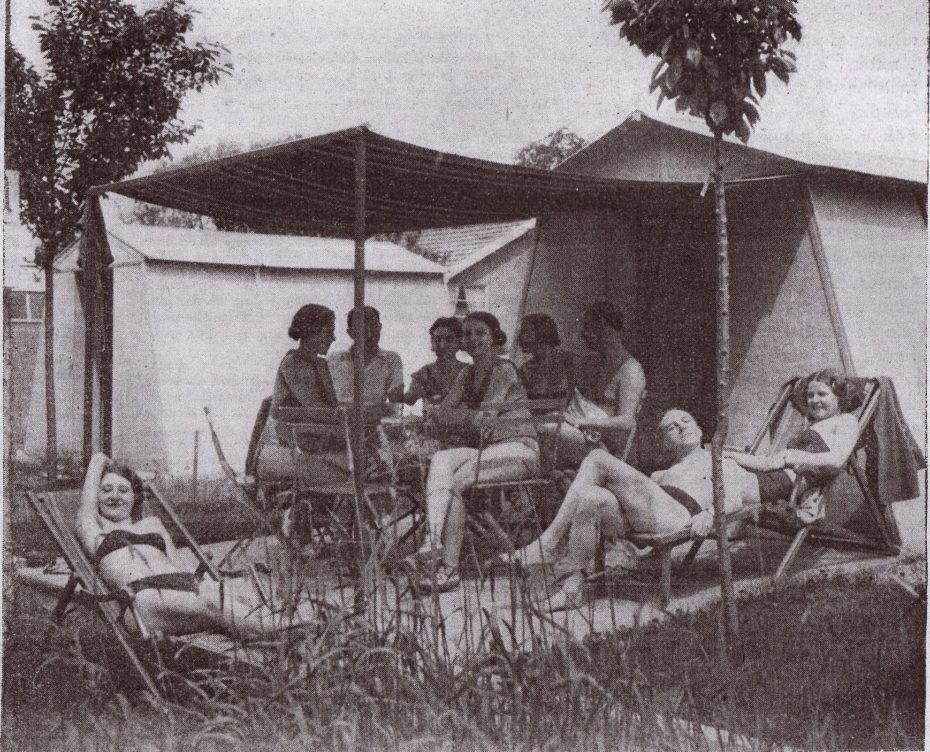

In Physiopolis, life was better in the buff. Or at least in a bikini, which was as close as one could legally get to public nudity in 1930s Paris. It was here, on an isolated sun-baked island on the Seine, that a titillating new naturiste-nudiste (naturalist and nude) movement sprang forth. Gone were the days of staying indoors to achieve a porcelain complexion like an Edwardian era prude. “The colour of health,” declared the founders of Physiopolis, was henceforth “found in shades of bronze,” and perfected through diet and exercise regimens to stimulate mind, body and soul…

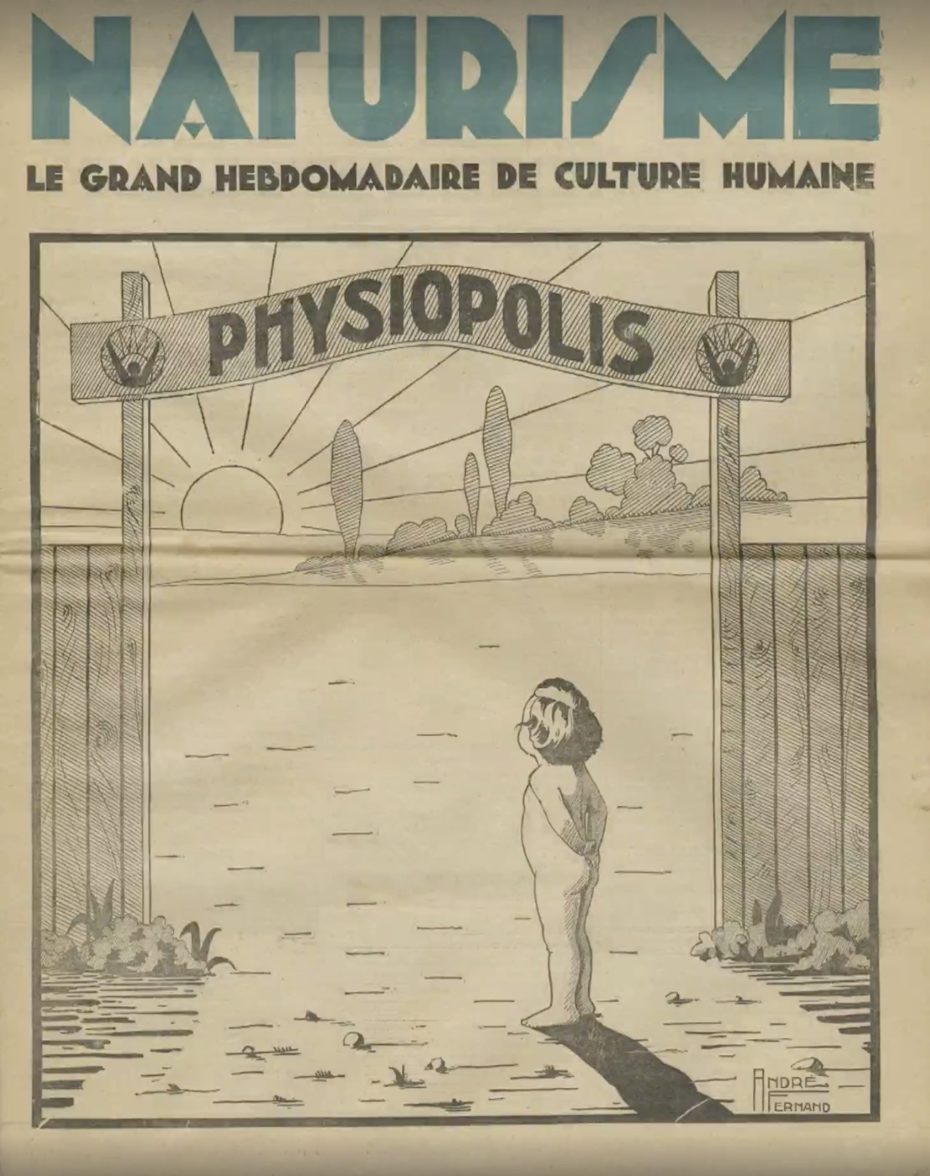

The nudiste-naturaliste movement was born in the inter-war period, from the brains of Parisian doctors André and Gaston Durville. The two brothers and collaborators shared a passion for the occult sciences inherited by their father, a pioneer of magnetic healing theories and “Egyptology”. In 1911, Gaston co-launched The Experimental Psychic Review to explore the medical healing potential of magnetism, hypnotism, psychology, mediums, and more, while André was busy presenting his research, “The Effects of Thinking on the Phenomena of Cellular Nutrition”. By the 1920s, they decided it was time to combine their strengths into the ultimate holistic health publication: Naturalism: the Great Magazine of Human Culture.

The zine’s pages were filled with lyrical tips on sunbathing, stretching, and the benefits of dropping one’s trousers. “Human skin wasn’t intended for the stuffy confinement of clothes,” they decreed, “nor to feel shy when it comes to physical activity, exploring movement, or feeling a gust of wind”. The public’s interest was officially piqued.

With the success of their magazine, the Durville brothers set up shop at 15 Cimarosa street in the 16th arrondissement (a private residence by the looks of it today). There were labs for radiology, electrocardiography, bacterial and chemical analyses – all in all, a very well-equipped centre that grew popular with curious Parisians. Most admirably, the brothers made sure their services were accessible to all, and made every Sunday a free day at the clinic.

Soon their clients craved more; a place to live out everything they’d learned in the fresh air, as nature intended. The little island of Platais, just a stone’s throw from Paris, was just the place…

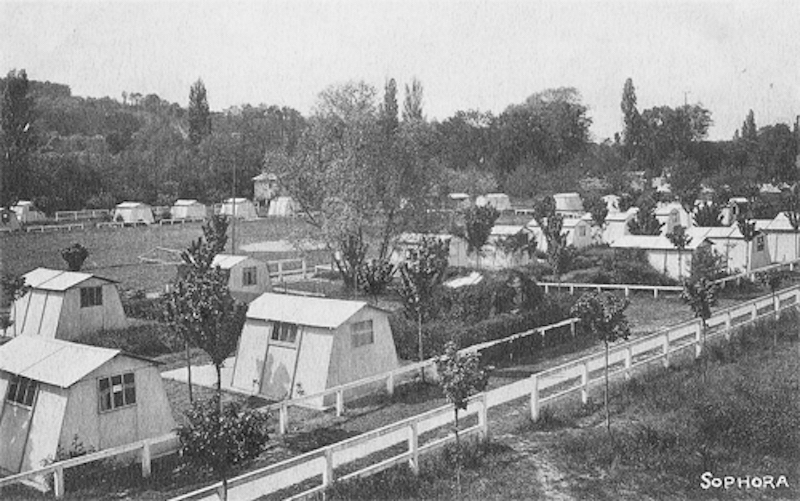

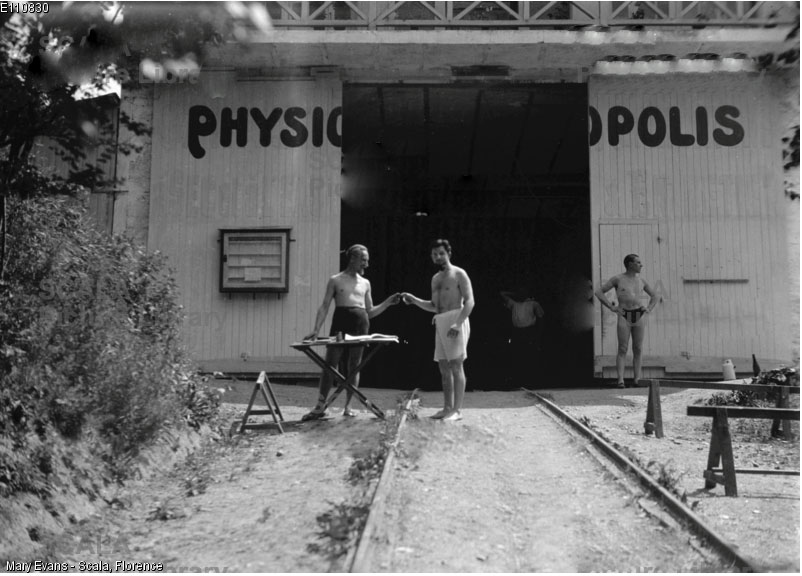

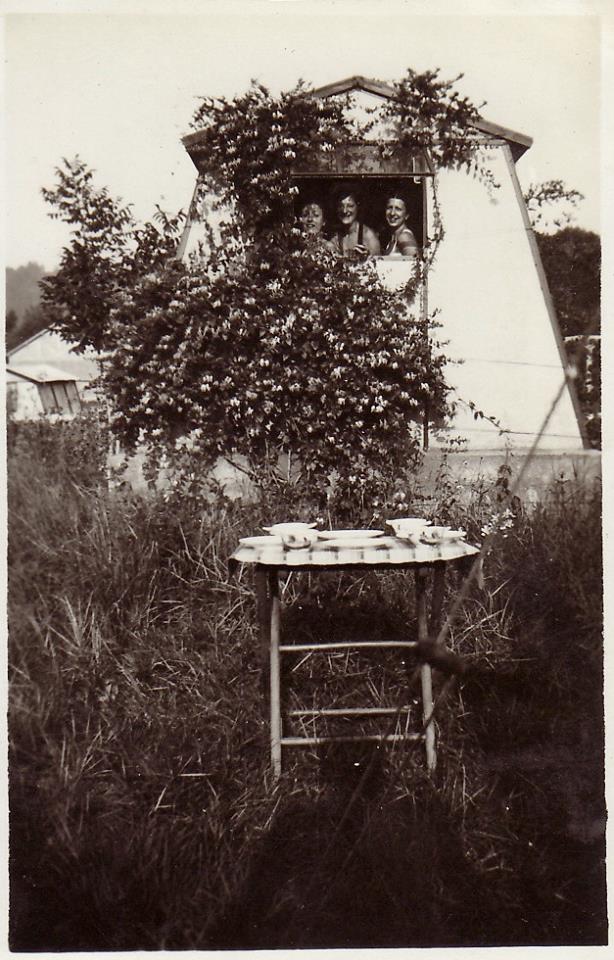

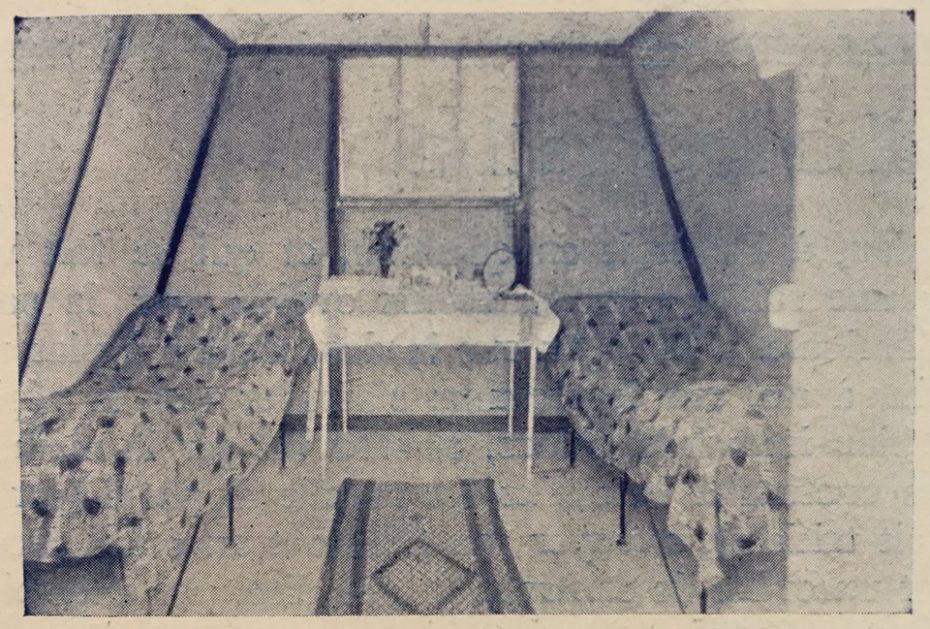

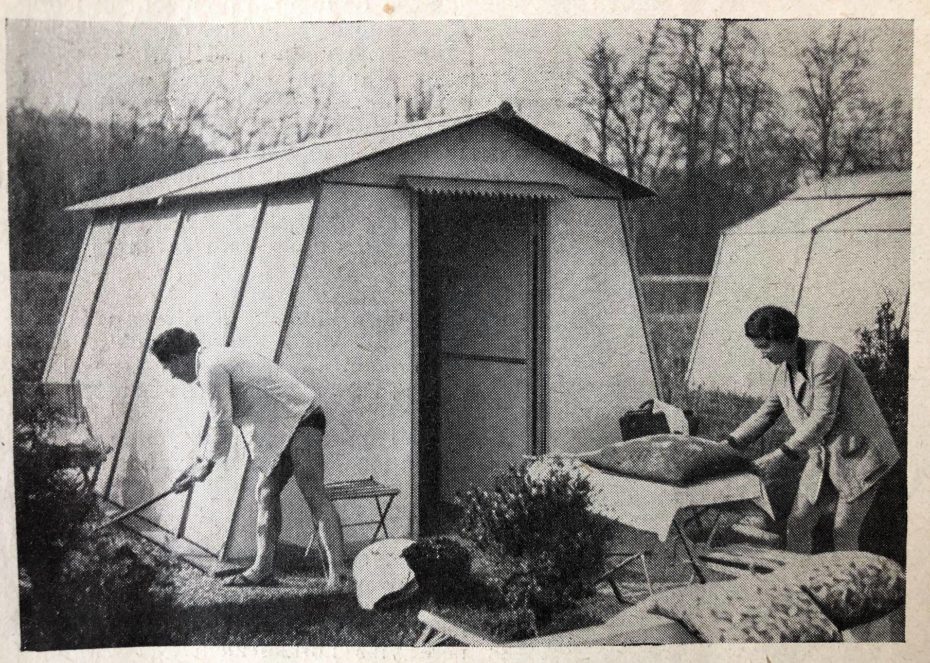

In 1928, it was re-baptised, “Physiopolis” by the Durvilles, who created little bungalows along a total of 11 hectares on the southern and northern tip. Their official insignia was a muscular figure saluting the sun, and the cornerstones of their doctrine proposed the integration of four interconnected “cures”: The Food Cure, The Skin Cure, The Muscular Cure, and The Moral Cure.

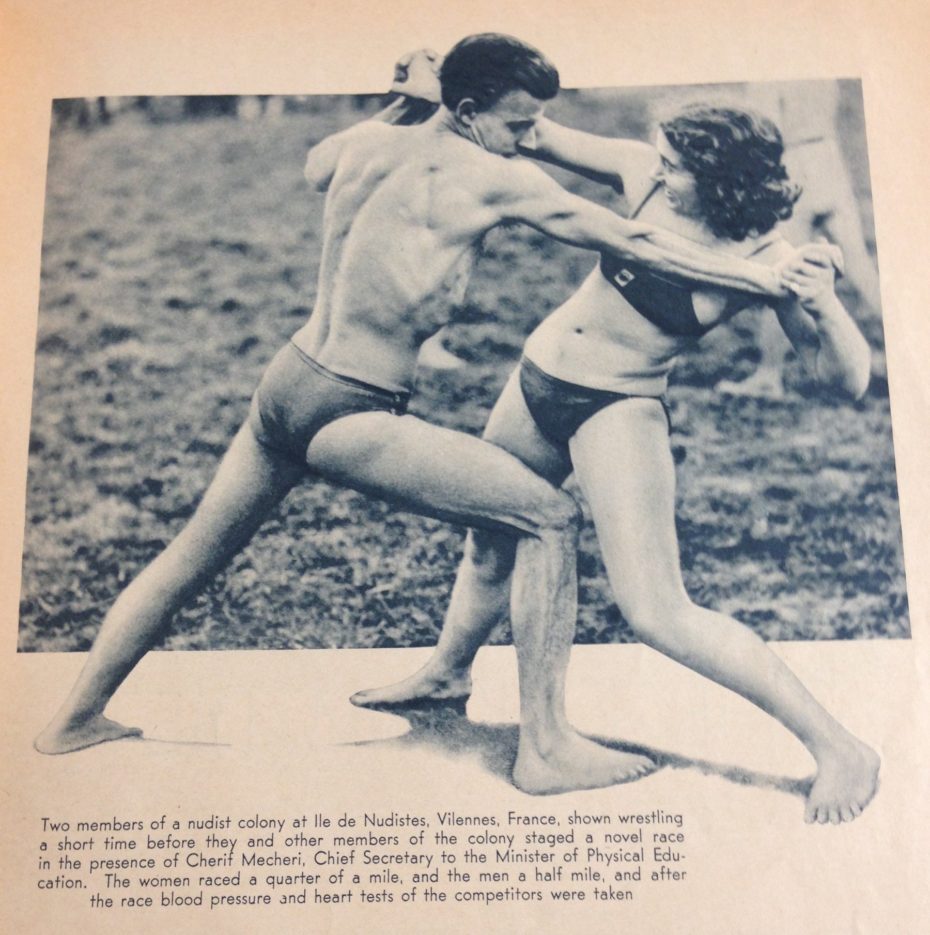

The first of their big spring gatherings garnered about 400 people, all of which were ferried out in little boats. “The naturist stadium is like a human factory,” they declared, “where we will manufacture handsome men”.

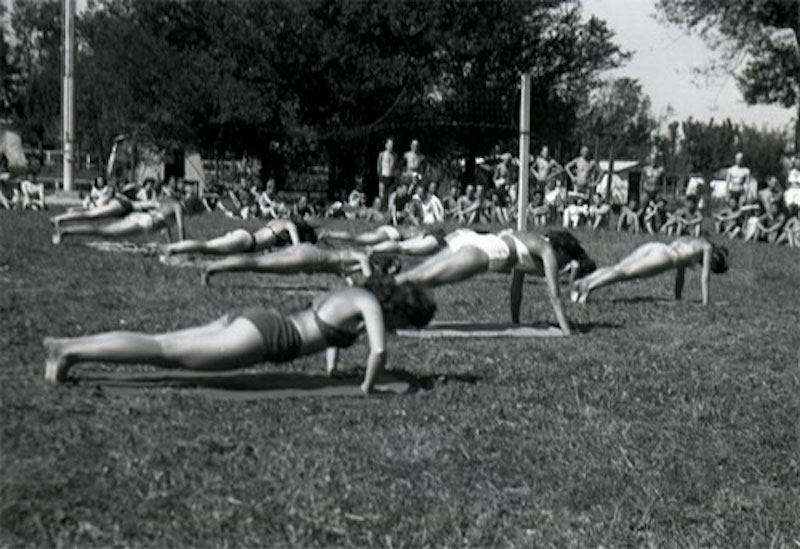

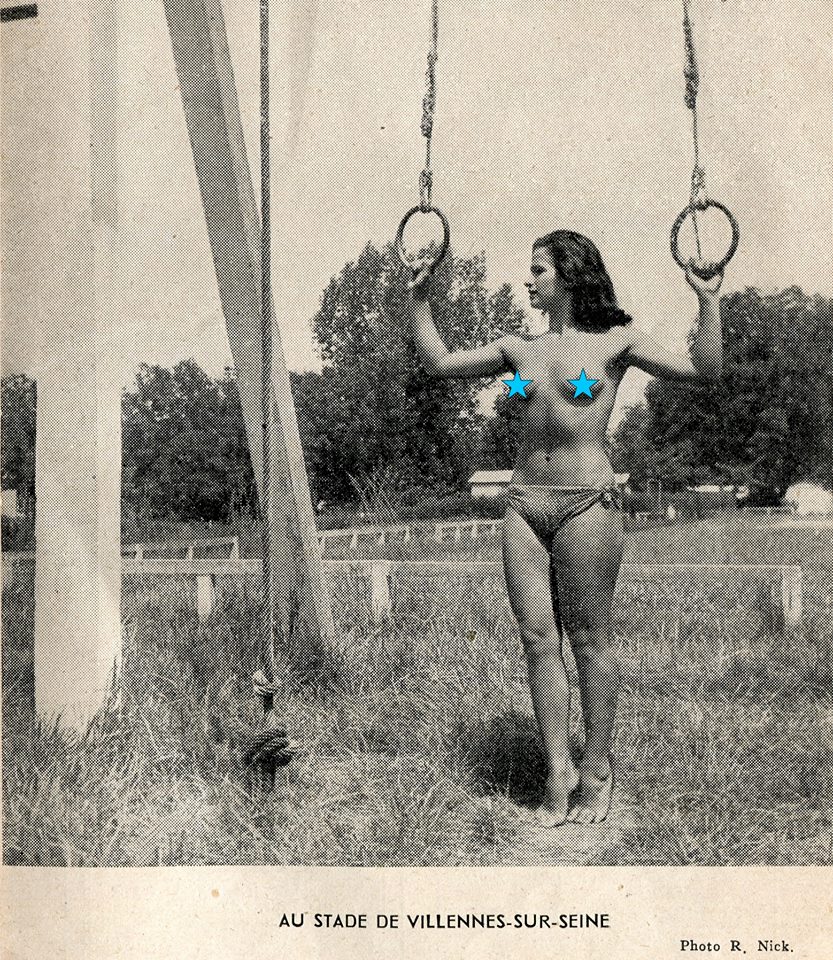

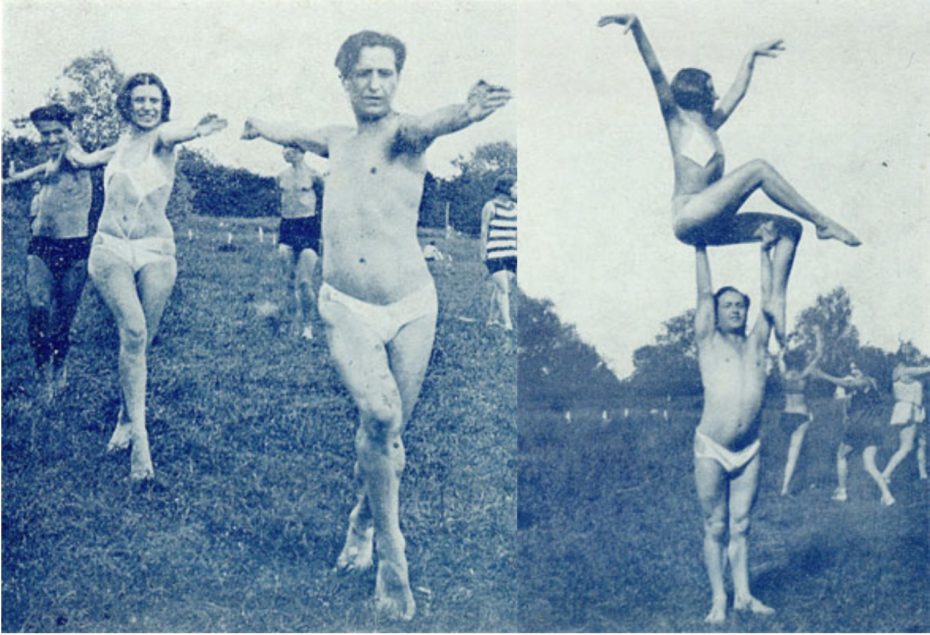

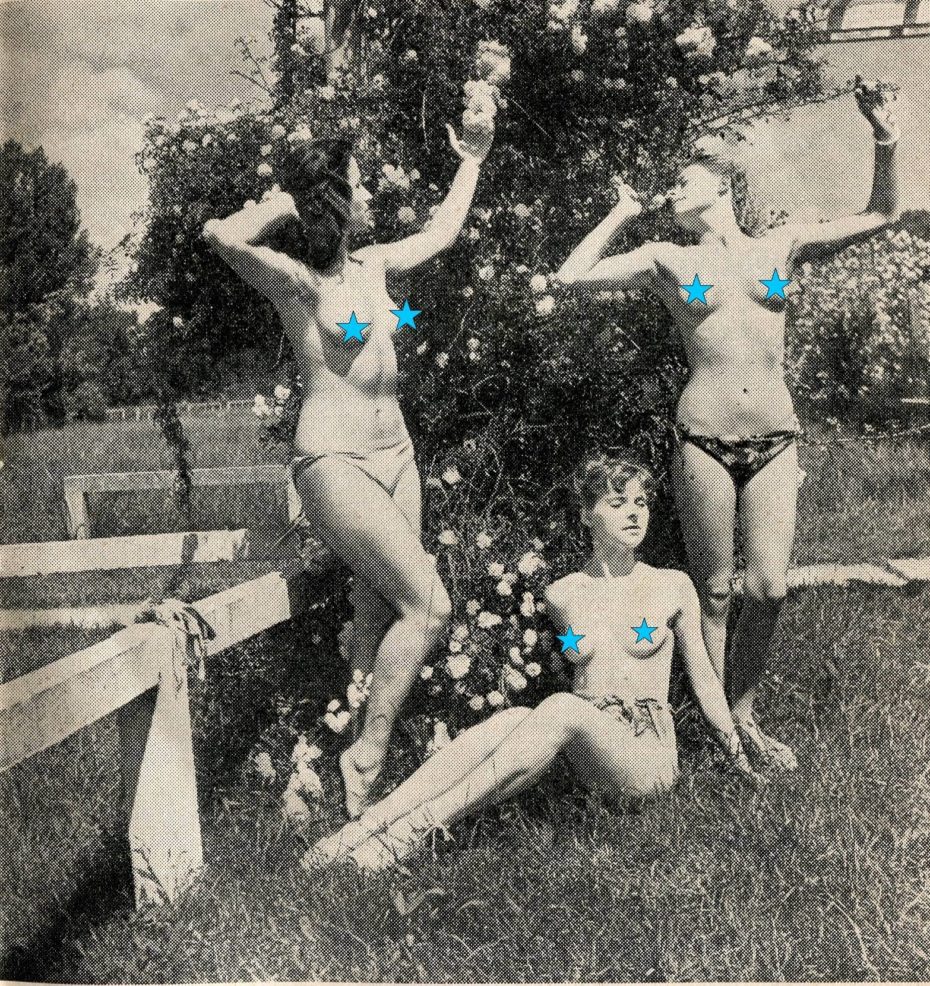

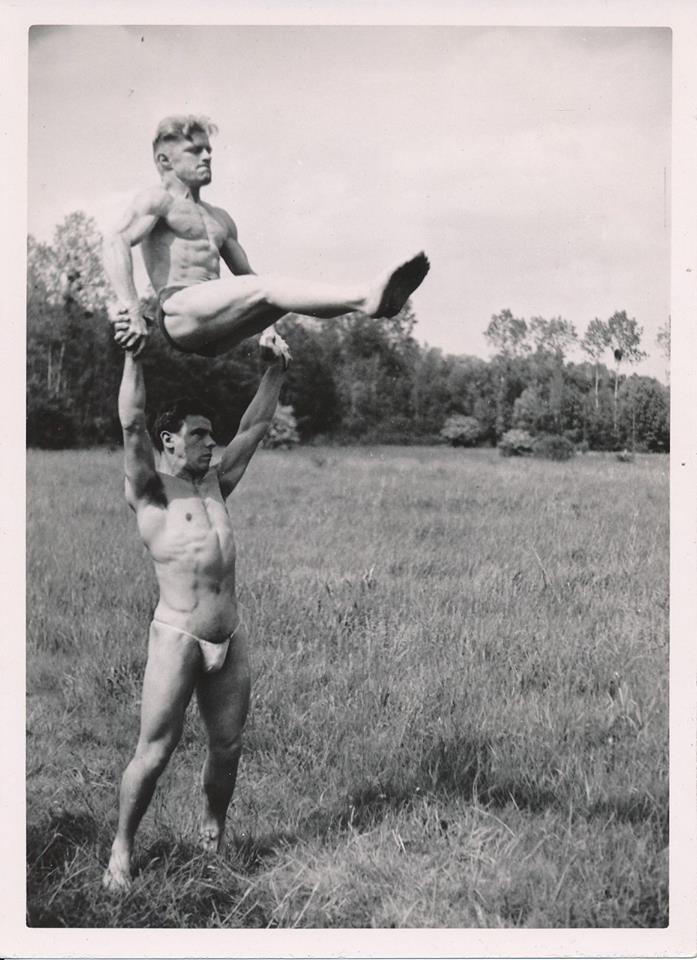

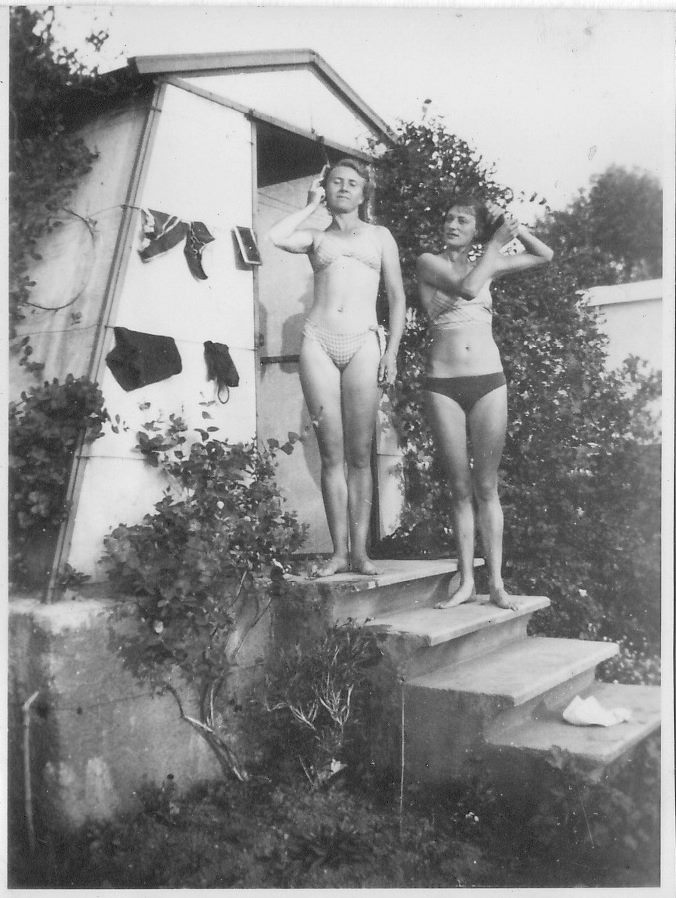

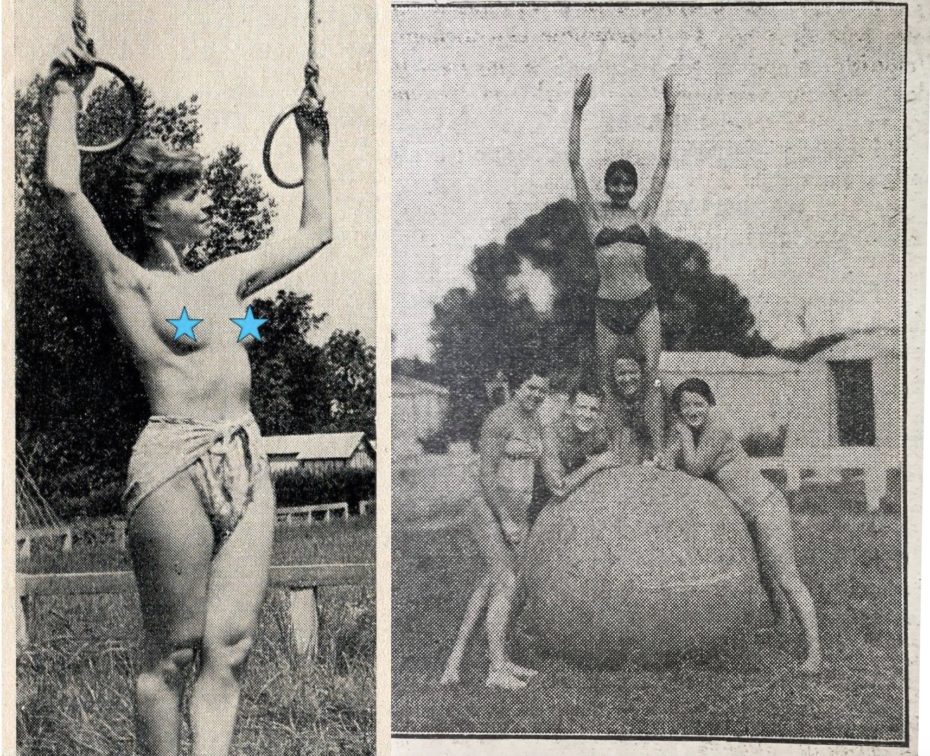

Men and women were encouraged to wear as little as possible, but in the beginning, many wore nothing at all to achieve what the Durville’s saw as “the truest sign of physical beauty: muscular definition” through various exercises that involved human pyramids, large balls, and monkey bars.

Jan Gay, author of On Going Naked, visited the island in 1931 and said “without being too harsh, one can call this island a pseudo-naked French Coney Island”.

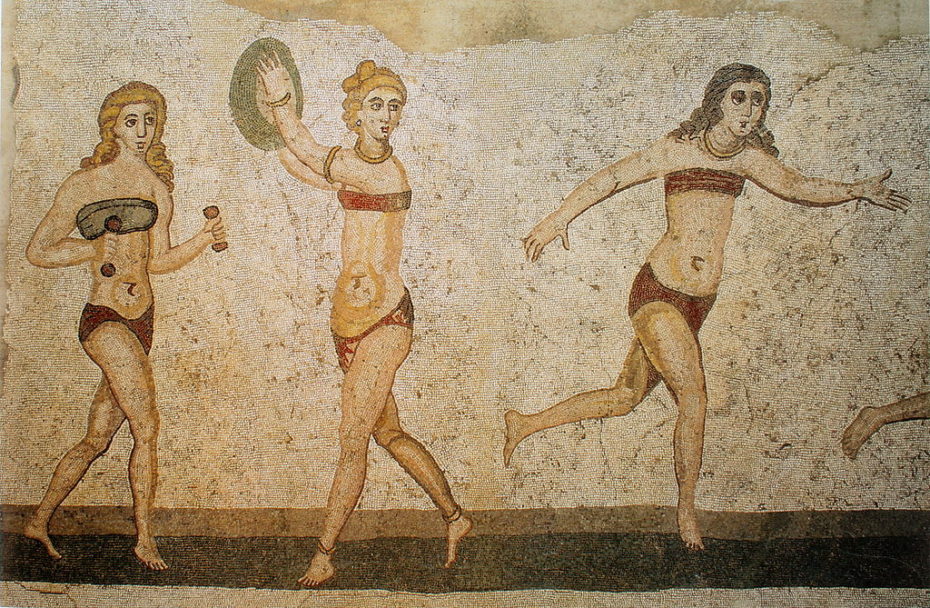

Physiopolis was inspired by Greek mythology and Ancient Rome, whose citizens first wore adopted two-piece skimpy garments centuries before the “bikini” was officially introduced to the world in Paris in 1946.

A diet of mostly “raw foods, fruit, and fewer industrialised products” was advised, as was a return-to-the-earth work manifesto. “Humans have lost touch with the earth,” they said, “Living in cities has dulled our senses, our natural intelligence and morality. We need an optimistic, nature-based education that encourages love for one another and our animal kin.”

Daily exercise routines looked something like this:

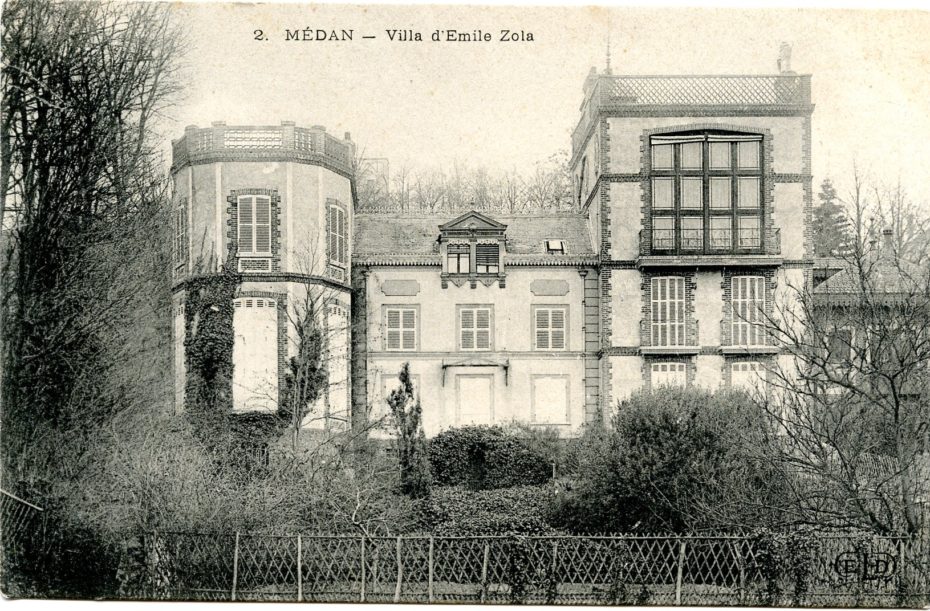

Even before the brothers Durville came along, this area had a special pull for Parisians. In 1880, the author Emile Zola had bought a little Norwegian style chalet across the shore (today a museum), and frequently invited his pals Cézanne, Manet, and Pissarro to find inspiration in its dappled island light.

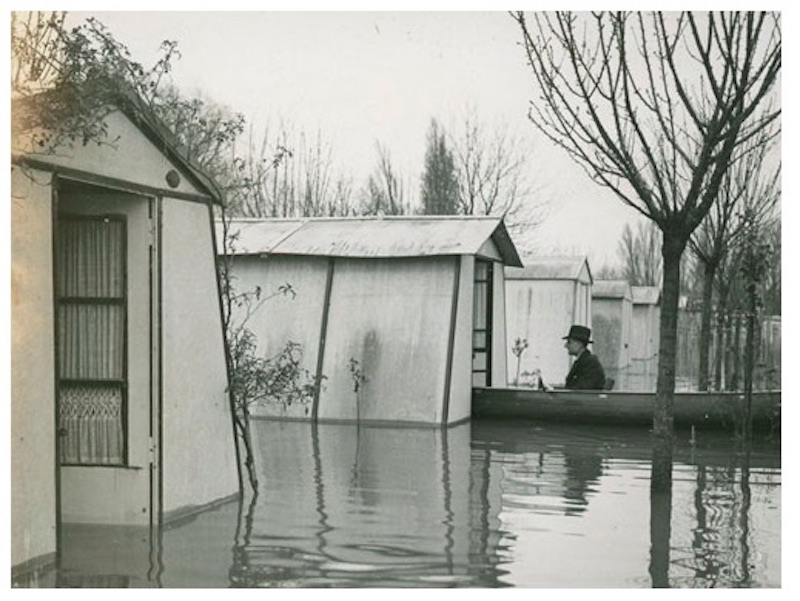

In fact, when Physiopolis began, a stretch of it known as “Villennes Beach” was already a popular seasonal escape, but the island’s susceptibility to flooding has always been its biggest setback.

The entire island was drowned in water during the winter of 1930-31. Luckily for the Durvilles, Physiopolis’ roaring popularity helped it bounce back.

Running Physiopolis wasn’t a cheap operation, but folks were willing to pay for it (the current equivalent of $2,000/year). The bungalows became even better equipped, and little roads were paved and given names like, “Champs Elysées Alley” and “Sweet Village Street”. There were also tennis, pétanque, basketball, and volleyball courts.

There were, of course, the critics – those who mocked Physiopolis as some kind secret bacchanal for societal deadbeats. “This place is crazy,” wrote one journalist in 1937, “These ‘brave’ people think that getting half-naked and throwing a giant ball for an hour will change the world”.

In the early, much more naked years, the Durvilles were pressured by authorities to keep their guests covered up. Their publication was declared pornographic and their site a “breeding ground for indecent exposure”, so they quickly rebranded themselves and required “slips” (cover-ups) for men and women in a dark colour palette.

The Durvilles also began purchasing plots of land to resell to naturalists in 56 metre-squared parcels, which ruffled a few feathers amongst members who thought conditions for purchase weren’t fair, as little autonomy was given to bungalow owners.

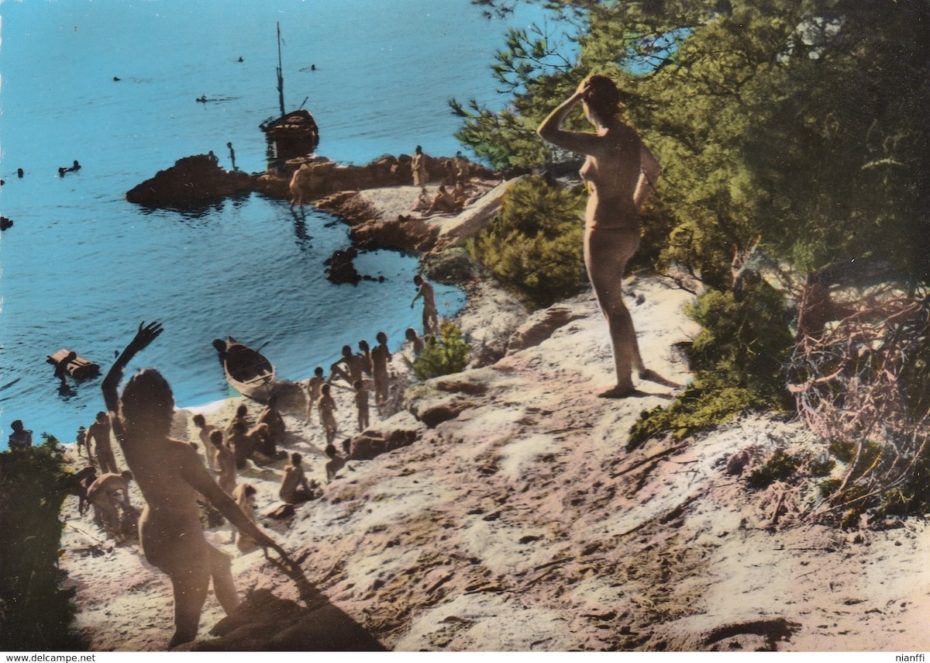

After the war, Physiopolis had also lost much of its carefree lustre, becoming more of a week-end fitness retreat than anything else. What’s more, the Durvilles attentions were diverted to their second thriving naturalist utopia, Héliopolis, on a French island in the Mediterranean where nudism was met with less scrutiny.

Today, in the US alone, the fitness industry is worth over $30 billion according to the IHRSA (International Health, Racquet & Sportsclub Association). Physiopolis was truly ahead of its time by presenting physical exercise not as an act, but a lifestyle. It also carved out a place for women to be strong and athletic over nearly a century ago – no small feat.

Yet the Durvilles brothers’ obsession with achieving what they called “the one true beauty: a muscular physique” didn’t wear well with time. Regarding one Los Angeles nudist camp, the Durvilles’ magazine reported, “we could have been spared the spectacle of a fat woman…they do not always possess the sort of statuesque physique created by our practices”.

Their idol worship of the “statuesque physique” was not only unrealistic, but, as historians point out, became increasingly exclusionary as men often returned injured or limbless or handicapped from war. In that way, the whole operation is a curious snapshot of life in those inter-war years, and of the fleeting space it made for some of the grandest, if not sometimes, delusional dreams.

Eventually, the brothers would publicly abandon their nudist philosophy altogether (but retain faith in secret) to attract a wider audience to Physiopolis. “In the end,” explains historian Stephen L. Harp in Au Naturel: Naturism, Nudism, and Tourism in Twentieth-Century France, “the Durvilles garnered wealth, public acceptance, and even official respect in the form of being named knights of the Legion of Honour” while Physiopolis’ glory years faded into the riverbanks, and the nudist party moved, in semi-clandestine fashion, to Héliopolis.

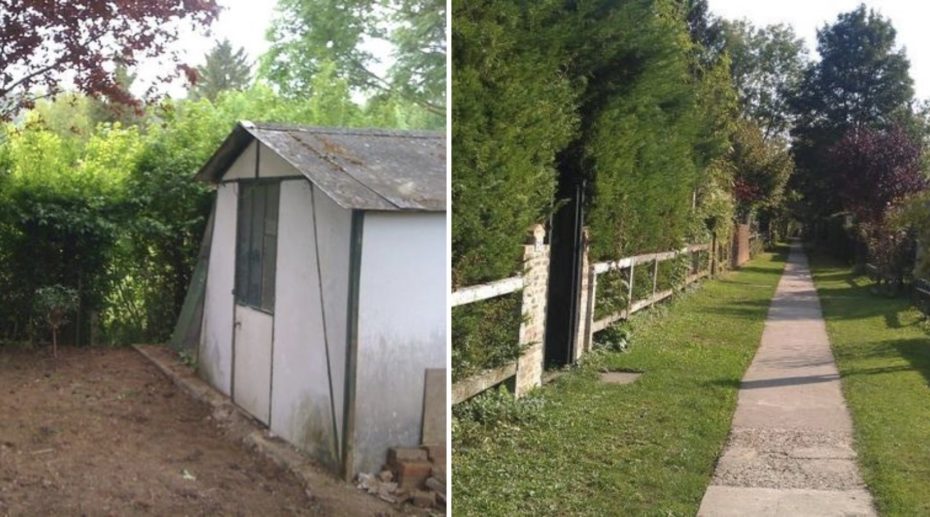

Physiopolis, by contrast, fell more and more into abandon…

By the late 1950s, it was a nudist’s utopia no more. The ageing colony’s strict health-driven values had gone out the window by the 1960s. Daily workouts for weekend visitors consisted of leisurely paddling in the pool and slow-paced games of pétanque. Flooding became more problematic, and the naturists stopped coming.

Adjacent to the island’s nudist colony, an Art Deco “aqua park” that opened in 1935 has been left to nature on another part of the island. Built on the grounds of Emile Zola’s former chalet, it once attracted thousands of visitors a year but closed its doors for good in 2002. The old restaurants and inns along the riverbanks are also in ruins. Zola’s house still stands but has been “under restoration” since 2011. There were plans to open it as a museum in 2018, but it remains shuttered and closed to the public.

This island has been largely left to its own devices for many years, its future tied up in disputes been the mainland and the islanders. Living on the Ile de Platais year-round is forbidden due to the risks of flooding but some 30-40 people call it their permanent home. We were informed by Cécile Juan, a photographer of the old bungalows, that the island’s “terrain and structures are run by syndicate groups today” and under private ownership. The residents live in a world apart, cut off from the nearby capital without public water shuttles to and from the mainland. Living amongst forgotten buildings of a failed utopia, they’ve only had electricity on the island since 2002 and have gained a reputation for being a very resourceful and tight-knit community.

Many of the neglected and abandoned Physiopolis cabins which can still be found on the island, dotted around the former domaine, and some have been given facelifts by local residents, whose parents would have purchased land as members of the colony in the early 20th century. Cécile suggested we reach out to the island’s official PR man (and syndicate member), but when we enquired with him for a comment about the current state of the Physiopolis cabins, he responded somewhat bluntly, “We only accept projects linked to the preservation of patrimony, [and] scientific and artistic research.” As we mentioned – it’s a tight knit community, not readily-accepting of outsiders. We did however find a waterfront property for sale on the former Physiopolis domaine, which boasts its very own 1930s-era cabin in the garden. Anyone interested in a fixer upper on the former Parisian nudist colony, apply here.

If you’re thinking about a day trip to explore the island, you’ll need to find yourself a boat to get you there. Hint: there’s a kayak club about 2km down river that will rent the enterprising explorer the necessary equipment for a summer adventure.