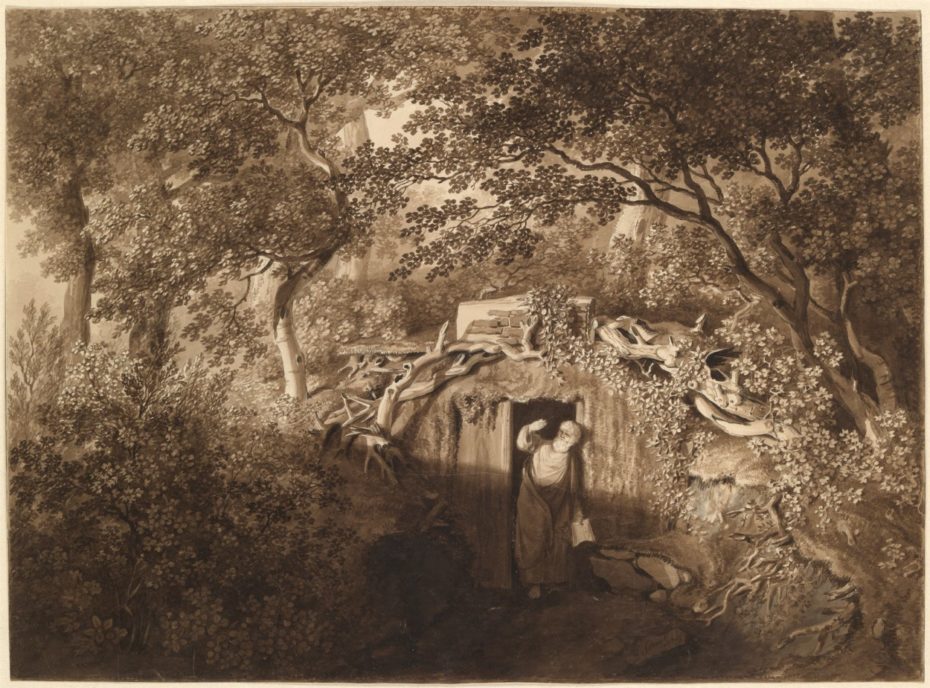

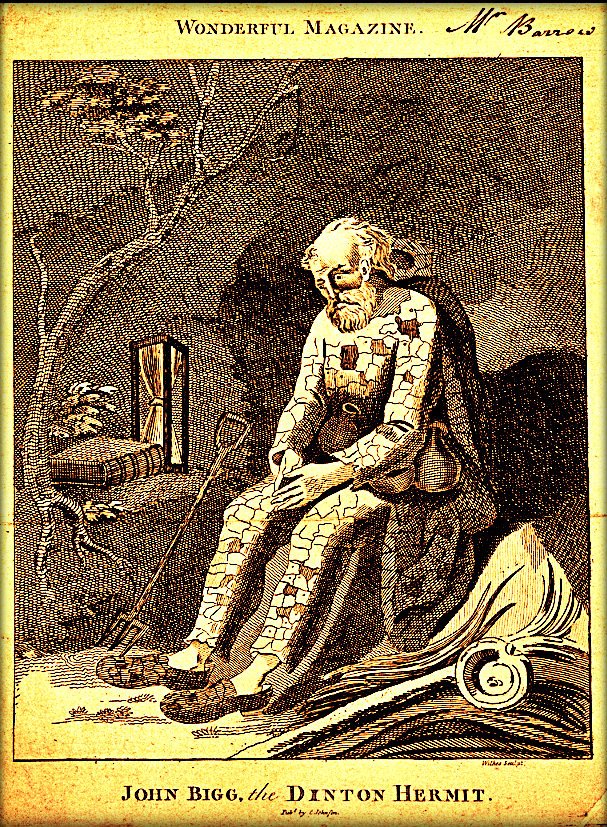

If you were out of a job in 19th century England and seeking new employment, there was a chance you might find a peculiar advertisement in the newspaper that read something like: “WANTED! Ornamental garden hermit“. The profession would essentially require you to become a human ornamental folly on the grounds of a wealthy family estate, whilst living in a cave (or cottage, turret, hole, etc.), contemplating the human condition and enchanting the occasional passer-by with your presence at the behest of the landowner. Fallen on hard times and looking a little too unkempt to work for fancy aristocrats? Fear not, the more witchy and druid-like your appearance, the better!

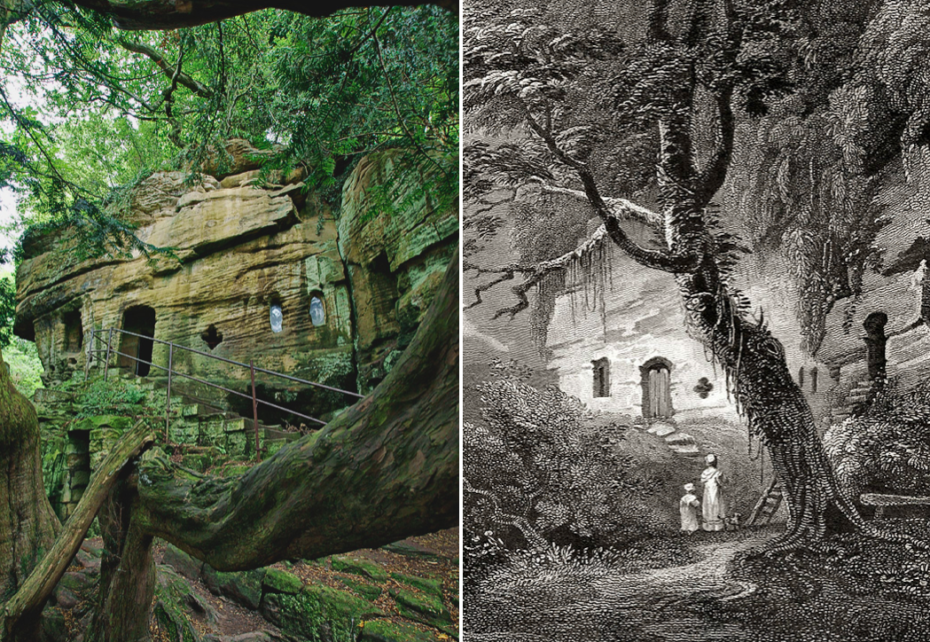

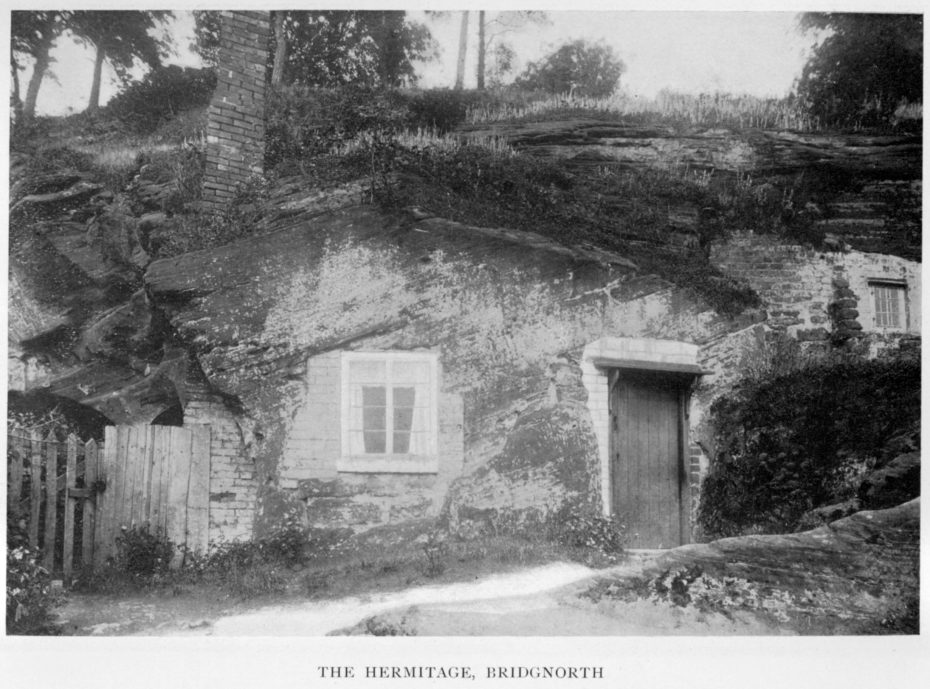

There are still a fair number of old hermit dwellings to be found across Europe, mostly in England, each tailored to the fantasy of its former land owner. Some were charming. Some looked like they were built by a drunk beaver. “The 18th century was the age of landscape art,” explains Tony Robinson in an episode of Worst Jobs in History. “I’m now a hermit,” he says jokingly, crouched at the mouth of an isolated grotto of an English estate. “[I am] the finishing touch to this beautifully sculptured garden. All I have to do is stay in my cave, and not speak to anyone or have a bath. Or cut my hair. Or cut my nails. And at the end of seven years, I get paid”.

He’s not kidding. Robinson is referencing the real conditions of one very intense aristocrat, Charles Hamilton, who couldn’t find anyone to meet his demands for more than three-weeks. However, a Mr. Powys of Marcham, near Preston in Lancashire, was able to keep a hermit on for four years with the following ad: A reward of 50 pounds a year for life to any man who would undertake to live seven years under ground without seeing anything human; and to let his toe and fingernails grow with his hair and beard, during the whole time…[in] very commodious [quarters], with a cold bath, a chamber organ, as many books as the occupier pleased, and provisions served from his own table.

Admittedly, not for everyone. But this hermit was compensated with ample reading material, a roof over his head, and the current equivalent of a £55,000 annual salary. The hired hermits were required to never, ever break character. Not even when the owners of the manor were off-property.

It’s hardly the first time society’s upper-crust have turned to big budget make-believe for catharsis. Marie Antoinette had her “peasants” hamlet; even Queen Elizabeth II still keeps her Wendy house in the gardens of Buckingham Palace (although luckily, she never kept ant hermits). As early as the Roman Empire, the seeds for the ornamental hermit were being sewn via the Emperor Hadrian’s secret villa. “In his villa he had a little pond. In the middle of the pond, he had a little house for one,” explains Gordon Campbell, author of The Hermit in the Garden, “[There], he could retreat from the horrors of running the Roman Empire”. When it was dug up in the 16th century by papal architects, it was decided that the Pope, too, needed a special place for alone time. Thus, “The Little House of Pope Pius IV” was born, and remains tucked under the Vatican to this day.

Fast forward a few hundred years, and the “ornamental” hermit became high-society’s must-have accessory. The true peak of #HermitLife popularity was ushered in by the Industrial Revolution, when people were pining for the contemplative landscape nature provided.

But what Lord of the manor had time to waste reflecting on life in a shady glen for an hour or two? So hermits became spiritual surrogates: a visual testament to their owner’s return-to-the-earth, introspective attitude. They were, stresses Campbell, “meant to reflect a kind of sobriety and melancholy”; ready to literally fondle a skull, à la Hamlet, at the drop of a hat (or the sight of a passing owner).

So yeah, it was hard out here for a hermit. Living amongst garden follies wasn’t exactly like living in Disneyland; these were architectural oddities whose shell-bedazzled grottos were easy on the eyes, but hard on the body, and whose twine-spun walls couldn’t have been fun in a storm.

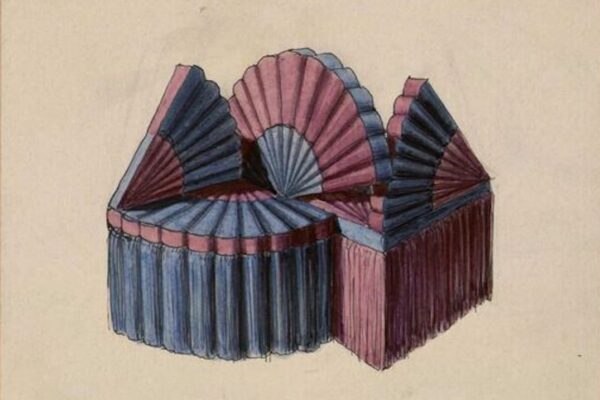

In William Wrighte’s 1767 guide to hermit house building, he advises on building both summer and winter-appropriate lodging, the latter of which he said “should be lined with wool or other warm substance intermixed with moss”. The summer house still sounds pretty prickly: “a simple affair paved with sheeps’ marrowbones and an owl stuck up on the roof”. Nevertheless, the jobs were in demand, and men actually put “hermit-seeking-master” style ads in papers to (in the words of one) “retire from the world”.

Dubris

In the best instances, hermitages could help the community at large. The 19th century sheriff William Danby, in Yorkshire, saw an opportunity to hire down-and-out residents during a severe period of unemployment, taking them on to build a Stonehenge-type temple and live on its grounds for seven years as “modern” druids.

Alas, as time wore on, the hermit fad faded. Downtown Abbey-esque estates were floundering through the world wars, and the expense of a flesh-and-bone garden gnome wasn’t top-tier necessary. Gordon Campbell’s book The Hermit Garden has a comprehensive list of the surviving (and destroyed) hermitages located around Europe.

It was much cheaper to hint at the presence of a hermit with, say, a wonky table set in the garden, or a statue hermit wearing one of the dunce caps they usually wore – you see where we’re going with this, right?

Of course, just when you think the weirdest bits of history have been forgotten, you come across someone like Stan Vanuytrecht. Two years ago, the retired Belgian artillery officer found himself divorced, and looking for a new passion project. Luckily, he found it in a continuously inhabited, 350-year-old hermitage in Austria:

He had to beat out 50 other applicants to get the gig (which comes with no electricity, no Internet, you name it). However, Sam is allowed — encouraged, even — to strike up conversations with the few wanderers who seek out one of Europe’s last hermits. His predecessor was a Benedictine monk who stayed for 12 years.

So the next time you roll your eyes at another tacky garden gnome in a hardware shop, remember: Not so long ago, those eyes would’ve rolled right back at you.