First things first: it’s not like we hate the accordion. We like it on the occasional metro platform, and we love to hear it in a distant summer breeze by the Seine. Few things are as effective at stirring up good ‘ole Parisian nostalgia, even after all these years. It’s just, well, a lot. It also turns out that our intrinsic dislike of the instrument may be due to its long history of being publicly satirised and berated by classical musicians. You see, by the time Yvette Horner was born in Tarbes (South-Western France) in 1922, the accordion was still relatively new to France. It actually has roots traceable to a Chinese instrument called “the Sheng”, was reincarnated as we know it in 1853 by the Italians, then moseyed over to the cobblestone streets of France in the 19th century. In Paris, it became known as the “Poor Man’s Piano” due to its easily transportable nature. The perfect way for buskers to make a buck at the Butte de Montmartre, or get the energy going at a bal populaire (public dance) and guingettes of provincial France.

Yvette was a piano prodigy, and grew up playing Beethoven, Chopin, and Liszt alongside 23-yr-olds in classes when she was just 11. Still, her parents knew that piano players were a dime a dozen in the music industry, and that if their daughter really wanted to stand out she had to do something drastically different. A female accordion player was unheard of, but for the rest of her life, Yvette looked back on the piano with a kind nostalgic tenderness. “My parents were very strict,” she told a French TV reporter in 1973, “I couldn’t rebel”.

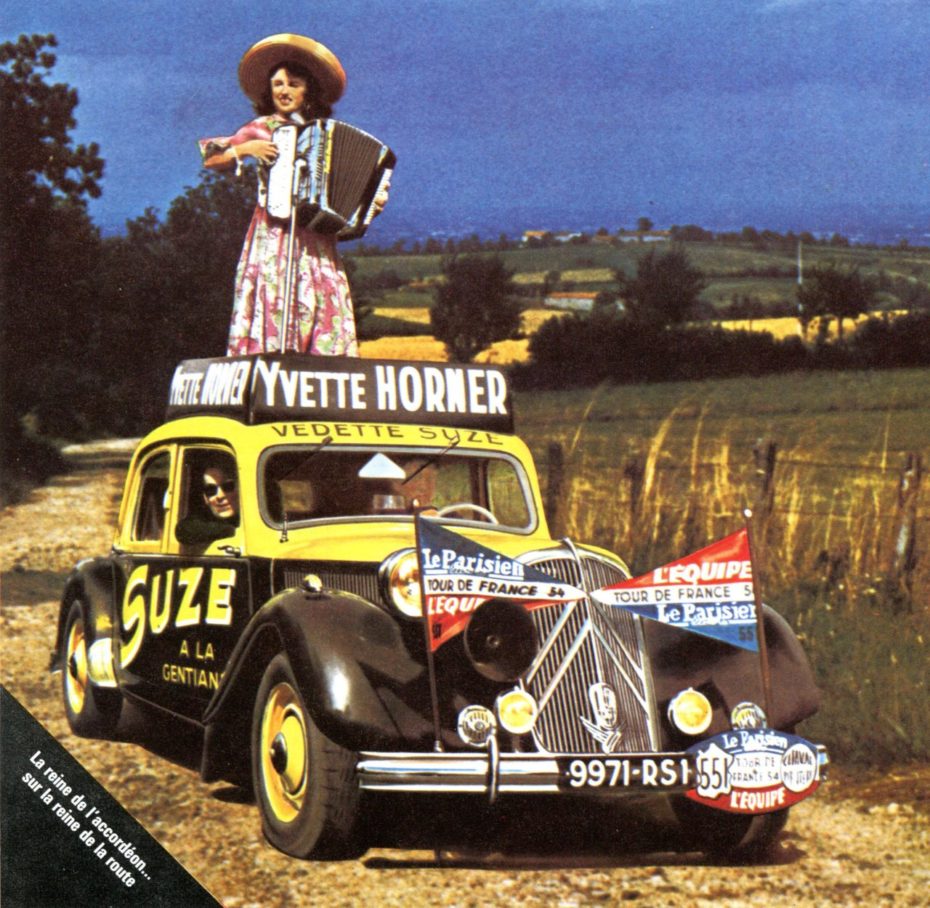

The novelty of a female accordion player captivated the nation, and soon, the world: in 1948, she became the first woman to win the Accordion World Cup (yup, a thing). In the years following the war, she becomes a vibrant symbol of French pride, riding atop a yellow Citroën Traction in the Tour de France for over a decade as the punny, gap-toothed cutie who always kept a bit of southern twang in her accent. It was her big break.

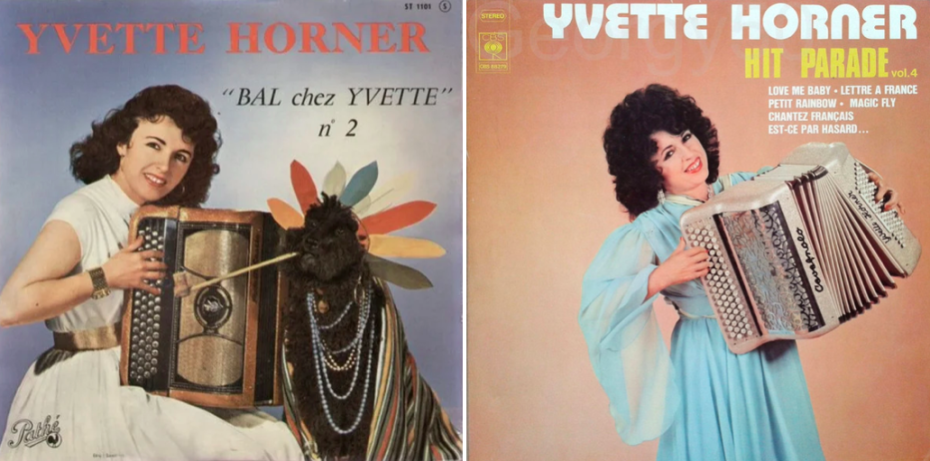

She was like Marianne, the symbol of French patrimony and perfection once famously modelled after Brigitte Bardot, but for les gens populaires. The albums rolled in, one after the other, as a testament to her truly inexhaustible work ethic, and fingers that played at the speed of light:

There’s arguably no instrument that demands as much attention as the accordion. It’s big, shiny, and rarely indiscreet. Yvette became the very embodiment of that spirit, with even her home in the Paris suburb of Nogent-sur-Marne transforming into a temple to the instrument. Accordion lights, accordion candleholders, accordion lamps — you name it:

But what about how inherently annoying some people find the accordion? “These people ignore that we’re playing on a very fine instrument,” she told a reporter in her living room in the ’70s, where a stately black piano rested behind her in the otherwise accordion-filled space, “[It’s] an instrument with which one can also play beautiful masterpieces. I did my best. I did my best to try, to play better and better. I guess you could say I gave [the accordion] a face – a name to associate with the instrument”.

In the years to come, she sold over 30 million albums, put out a total of 150, and presented a range for musical genre that you might not expect from the accordion. She even put out a country album and played the Grand ‘Ole Opry.

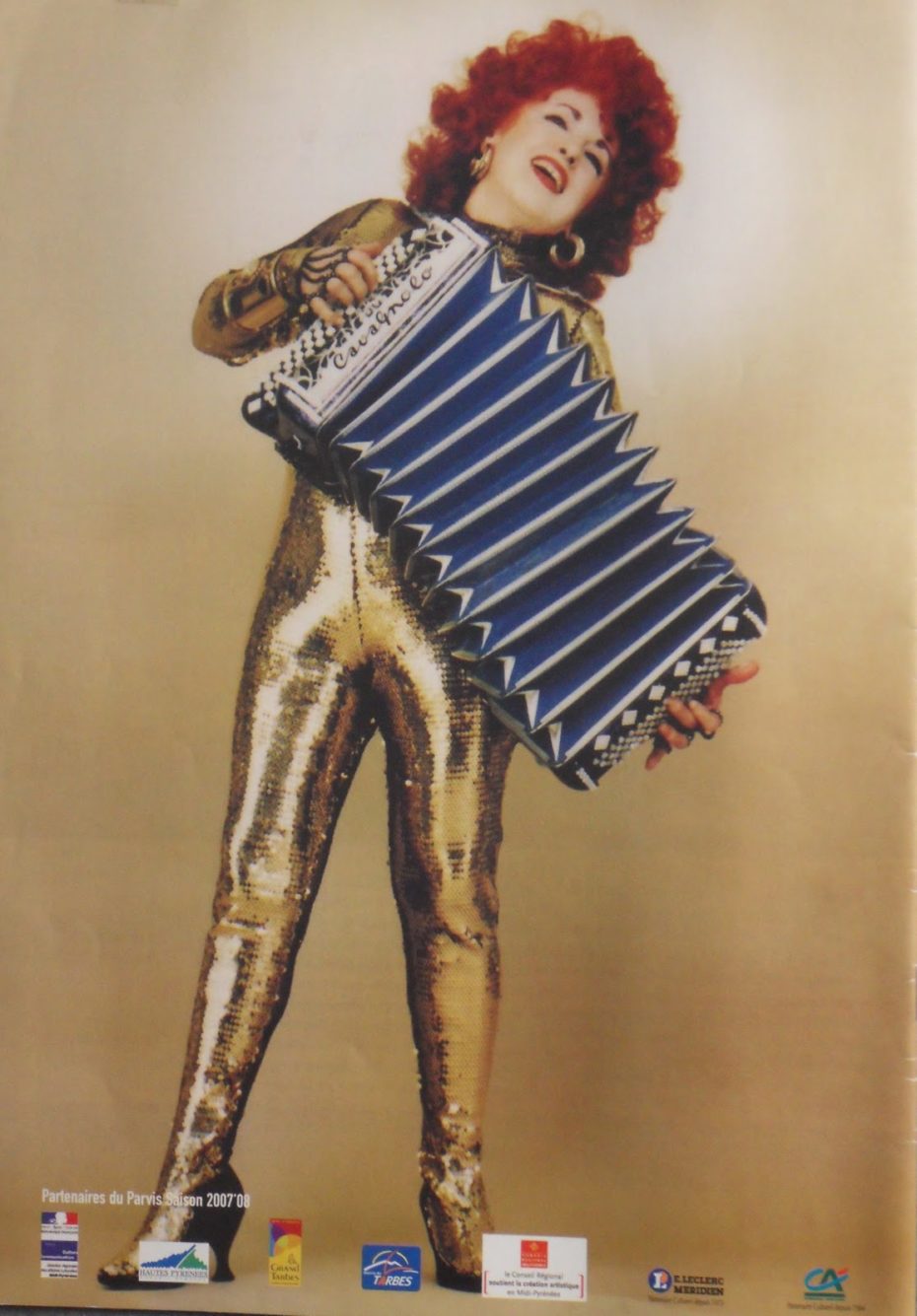

In the 1980s, things reach a new all-time high for Yvette when she makes a new friend: Jean-Paul Gaultier. The then up-and-coming designer transformed her French-girl-next-door look into one of Liberace-level splendour. Her hair, once a mousy brown, became a fiery red…

Most of all, her wardrobe became a sparkly treasure trove of campy outfits, from accordion skirts to golden jumpsuits; polka dot frocks to an iconic Eiffel Tower dress, which she wore in a questionable Eurodance track (yet another genre!) that she did in the ’90s with a DJ called Andy Shafte. Catch it at the end of the music video below, which is basically a four-minute Gaultier ad:

It was thanks in part to Gaultier’s eye for iconic styling that Yvette’s career got the final push for cultural staying power. Seriously, she even did a song with Boy George, and put out her last album, “Hors Norme” (Out of the Ordinary) in 2012. In that sense, she can be added to the list of Gaultier’s greatest muses, right up there with Madonna, Rossy De Palma, and Amanda Lear:

“Yvette, along with her accordion, was the soundtrack to my childhood,” Gaultier said upon her death in 2018, “Quite simply, Yvette was just pure love”. Their partnership, though ostensibly odd, was the perfect union: Gaultier loved playing with French clichés (ex. those revisited Breton striped t-shirts!). Yvette was the biggest French cliché there was, in the flesh. It’s safe to say that no other person in history had her talent for taking the most potentially obnoxious instrument in the world, and making the world listen for over half-a-century.