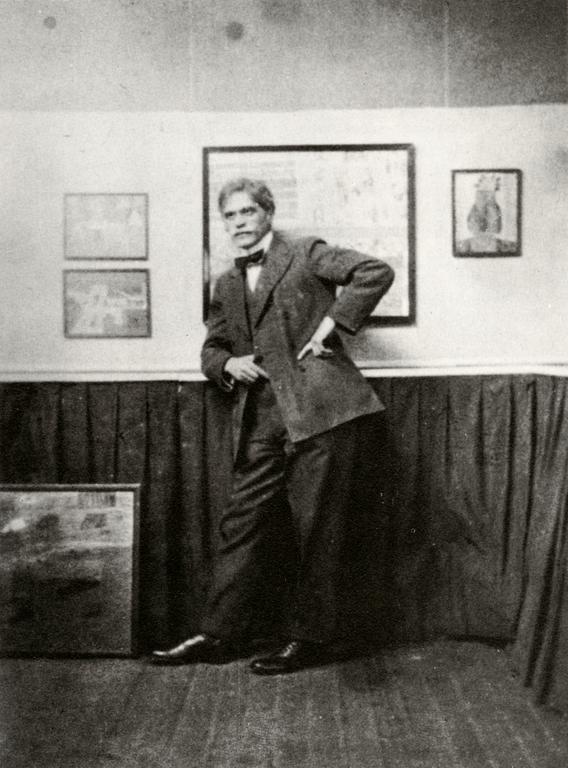

Did they ever tell you about the nice Jersey boy who brought Modern Art to America’s shores? It wasn’t a Rockefeller, or a Guggenheim – just a kid from Hoboken, New Jersey with an eye for talent. Behind the doors of a little 5th floor attic-level apartment on 291 Fifth Avenue, he displayed raunchy Rodins, cock-eyed Picassos, out-there Brâncușis, Matisses, Cézannes and gave the American public its first taste of the controversial European avant-garde. Many of modern art’s household names all found a launching pad at the space that would become known as “291”; numbers that would act as shorthand for artistic excellence. For “if you go there often enough,” photographer Francis Bruguière said, “you will find just how big or how small you are”.

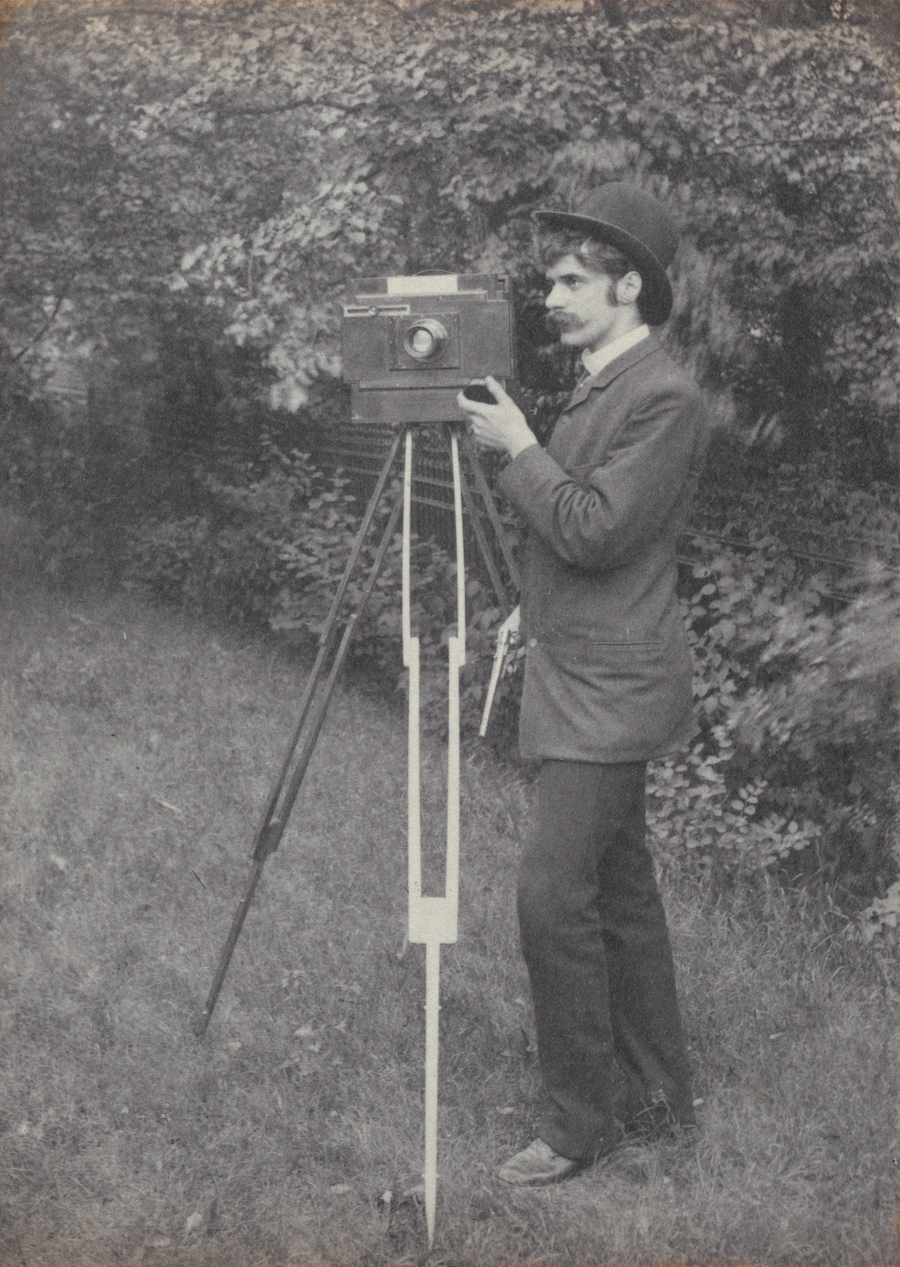

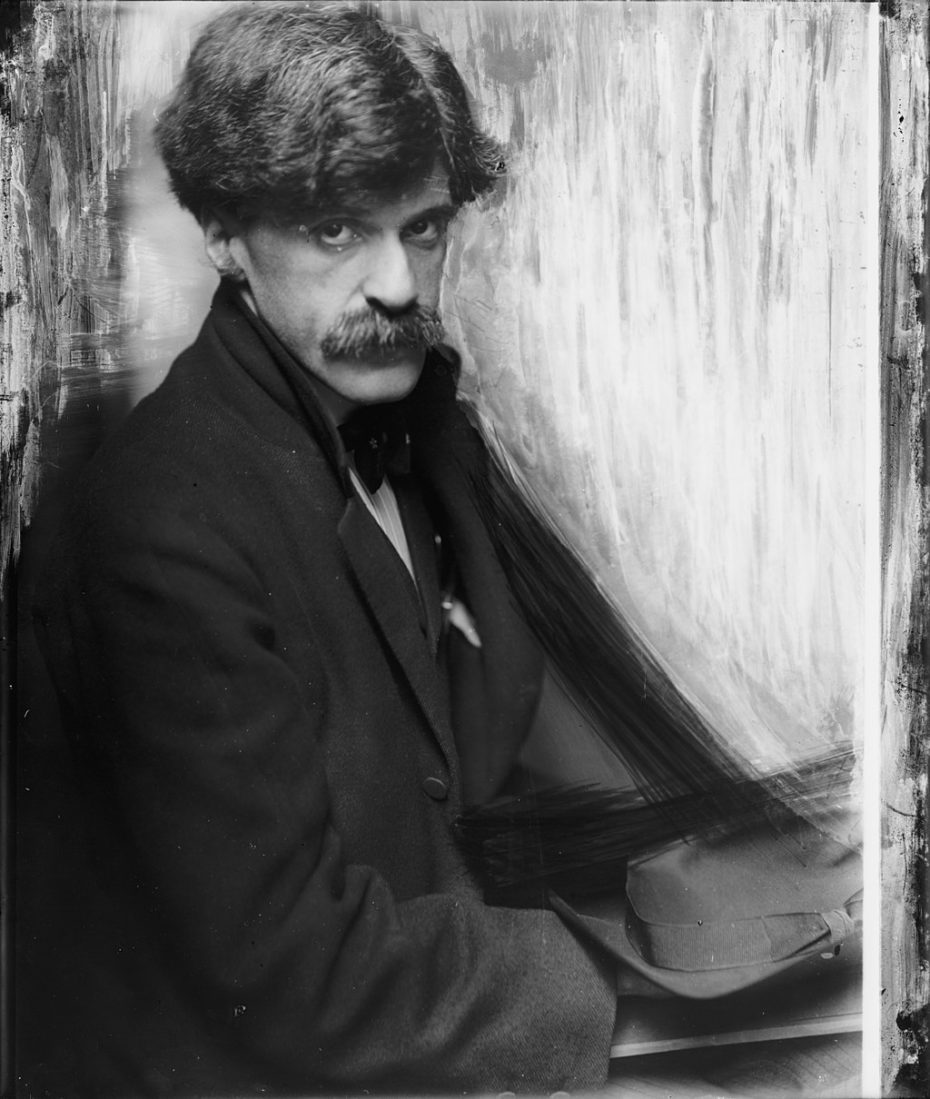

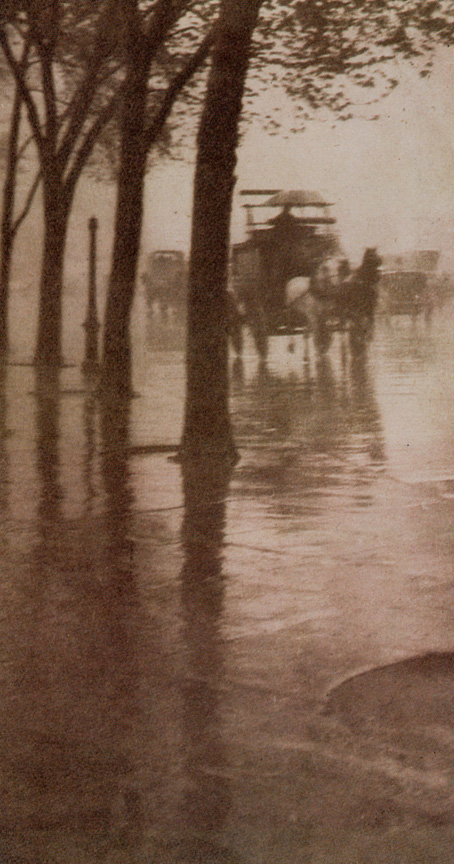

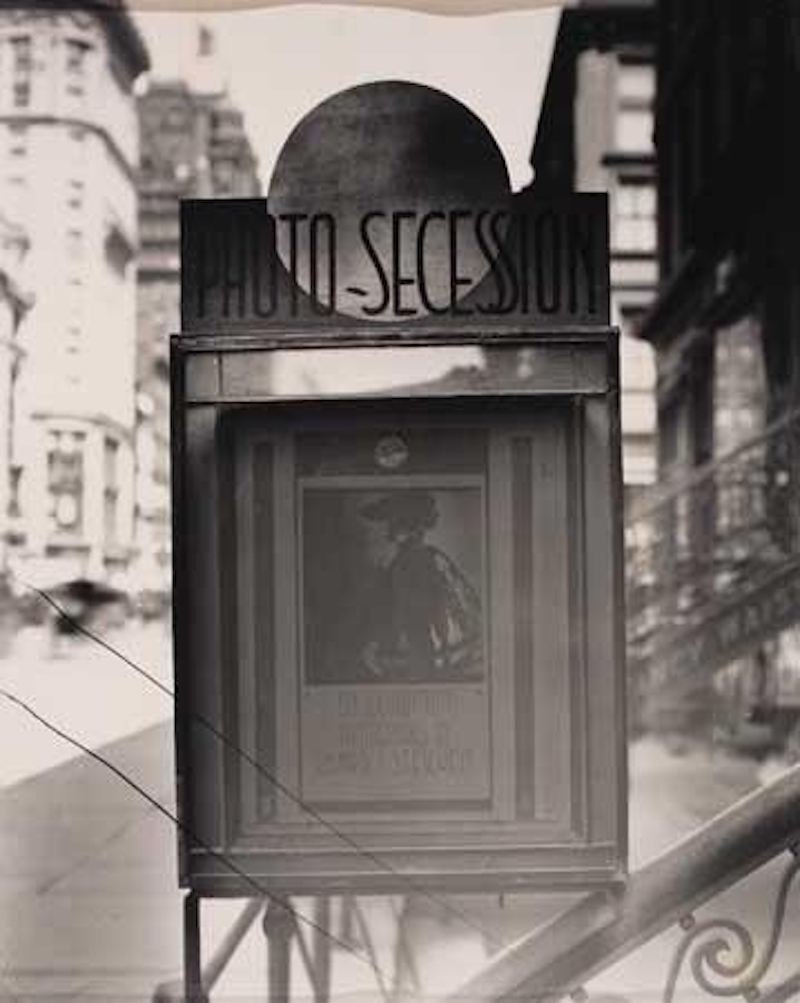

The first son of German Jewish immigrants, Alfred Stielgitz grew up in Jersey before spending some of his most formative years getting a higher education in his motherland of Germany. It was there that he trained his eye as a photographer and formed the Photo-Secession movement, an aesthetic that centred around photo manipulation long before Photoshop and helped photography find its place as a true art form. Stieglitz was determined to show critics that photography could be used to “create” an image rather than simply record one, and that it was just as innovative, creative and serious a medium as painting or sculpting.

Alfred Stieglitz

Spring Showers, The Coach(1902)

by Stieglitz

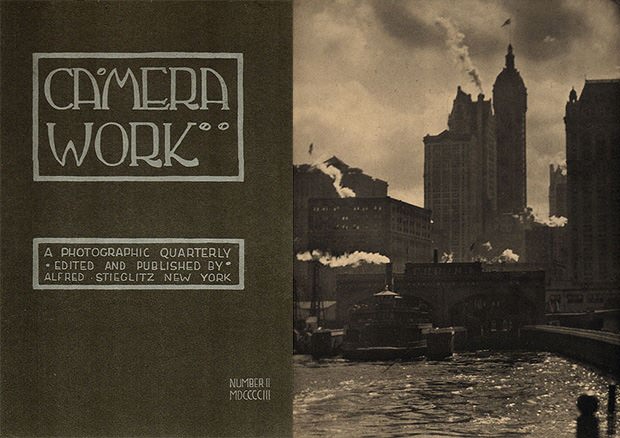

With a core group of like-minded photographers, upon returning to the United States, Stieglitz organised an exhibit of Photo-Secessionist pieces at the renowned National Arts Club in New York City in 1902. In the coming year, he also founded the journal Camera Work to promote the philosophies and work of the Photo-Secessionists. Soon enough, he decided the movement needed a physical home, not only as an exhibition space but as a meeting place for artists, photographers and art lovers…

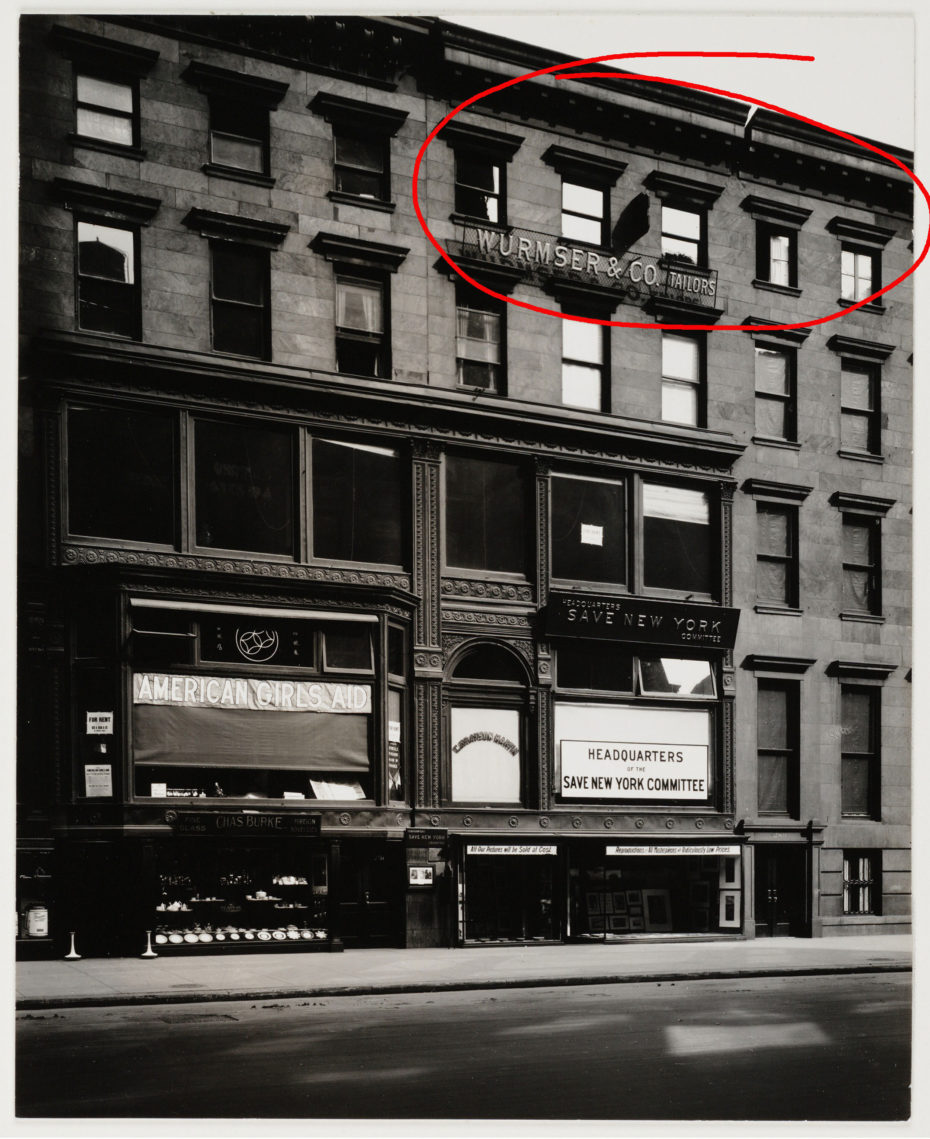

Of course, when you’re operating on a shoe-string budget, you can’t be picky. Enter Edward Steichen (pictured above far right), the painter-turned-photographer who befriended Stielglitz at the turn of the century and whose work was frequently featured in the Camera Work journal. Edward was one of the first people in the United States to use the Autochrome Lumière process and was famously “dared” by journalist Lucien Vogel to promote fashion as a fine art through photography. (Two decades later, he would become one of the highest paid photographers in the world for Vogue and Vanity Fair). Joining in on his friend’s hunt for a gallery space, Edward noticed three rooms for rent across from his own tiny studio on 291 Fifth Ave., and convinced Stieglitz to sign a year lease on all of them. Thus, in 1905, “The Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession” was born…

Little did the two men know that in a matter of years, those three attic-level rooms would become veritable portals to artistic enlightenment.

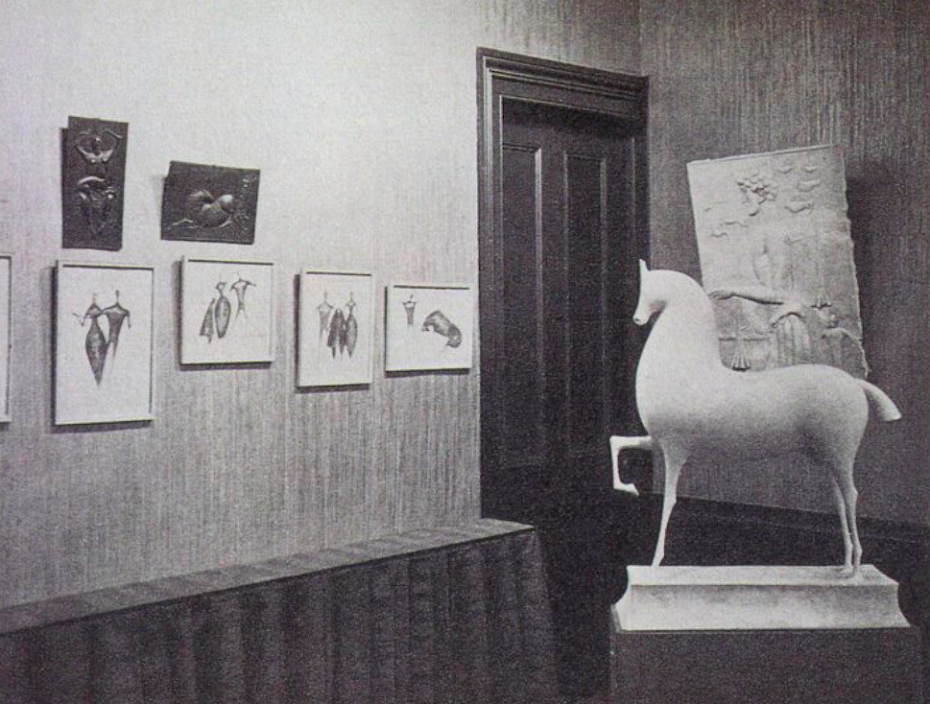

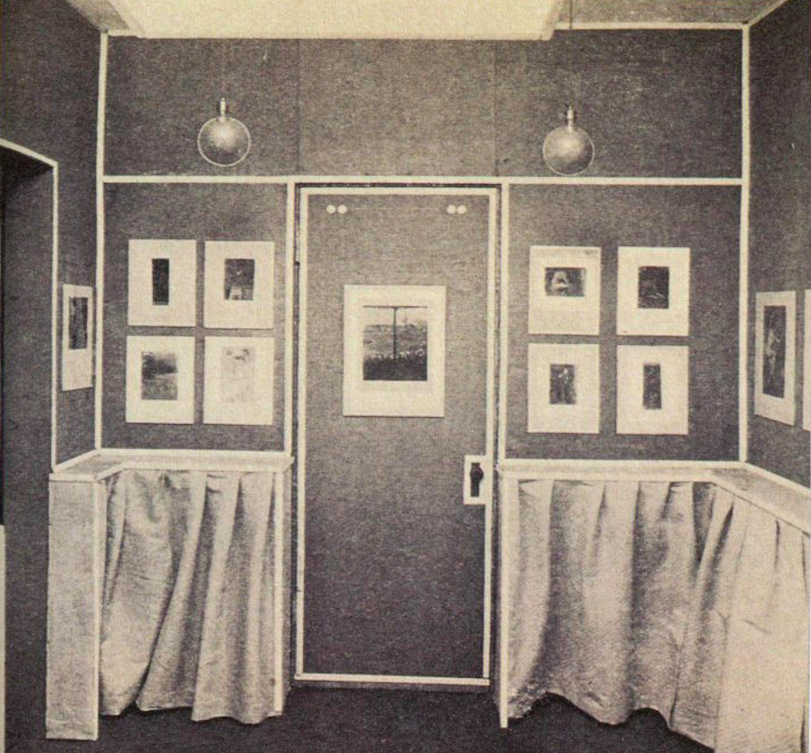

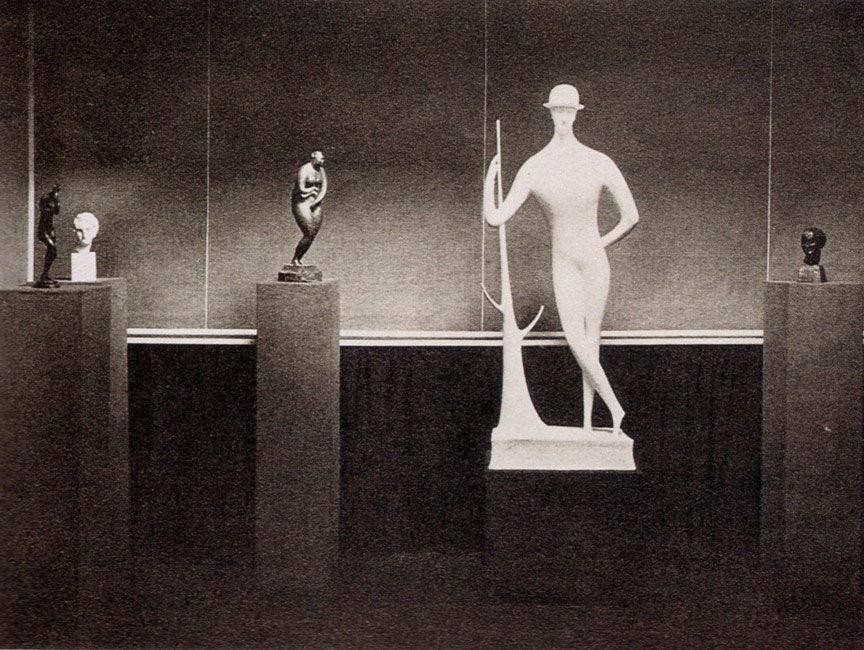

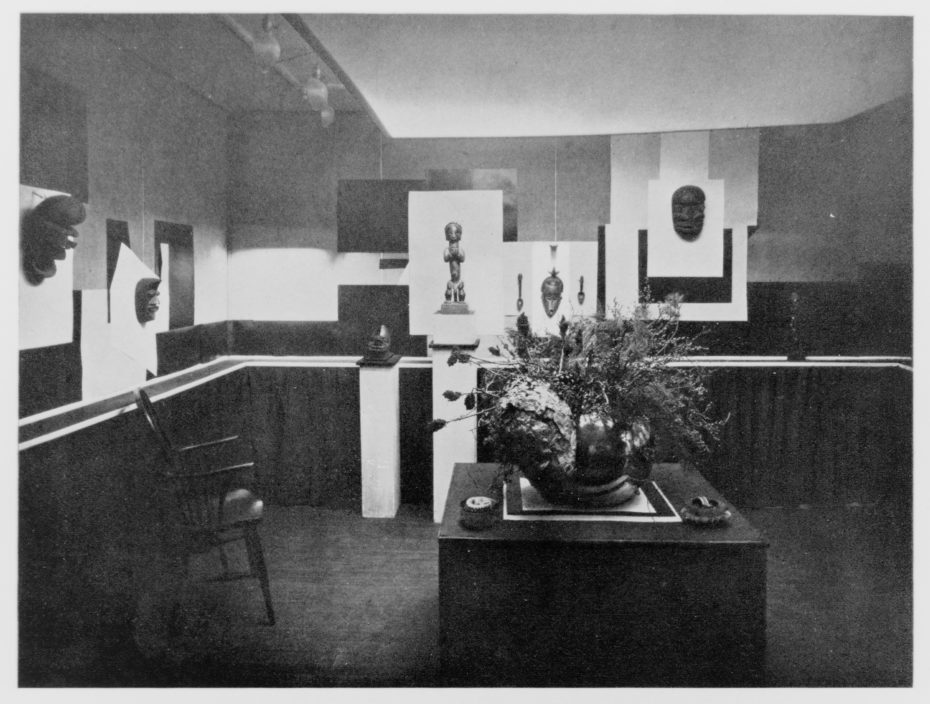

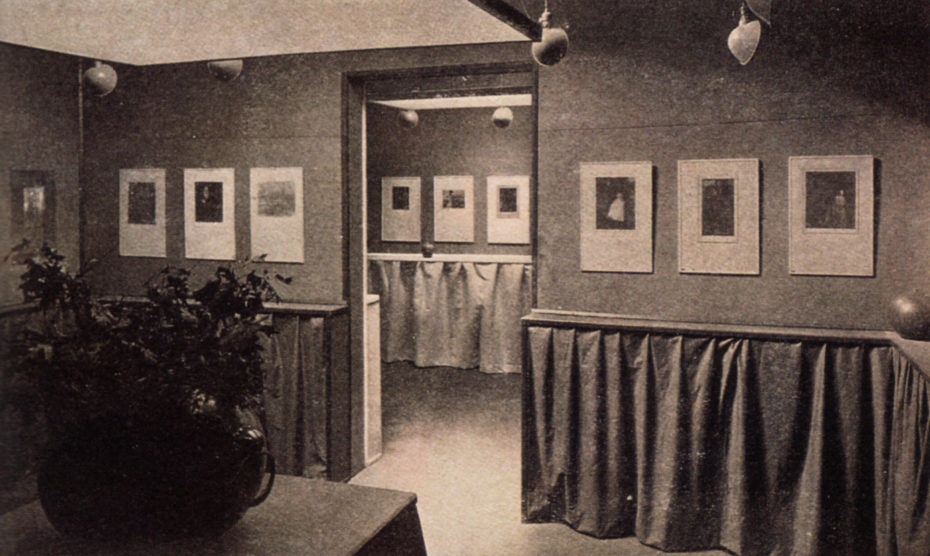

It was a sense of mystery in those early years that made it such a success. A formal opening date wasn’t even released, but hundreds flocked to the apartment gallery over the coming weeks to see 100 photographs pinned up to the walls, all painstakingly selected by Stieglitz.

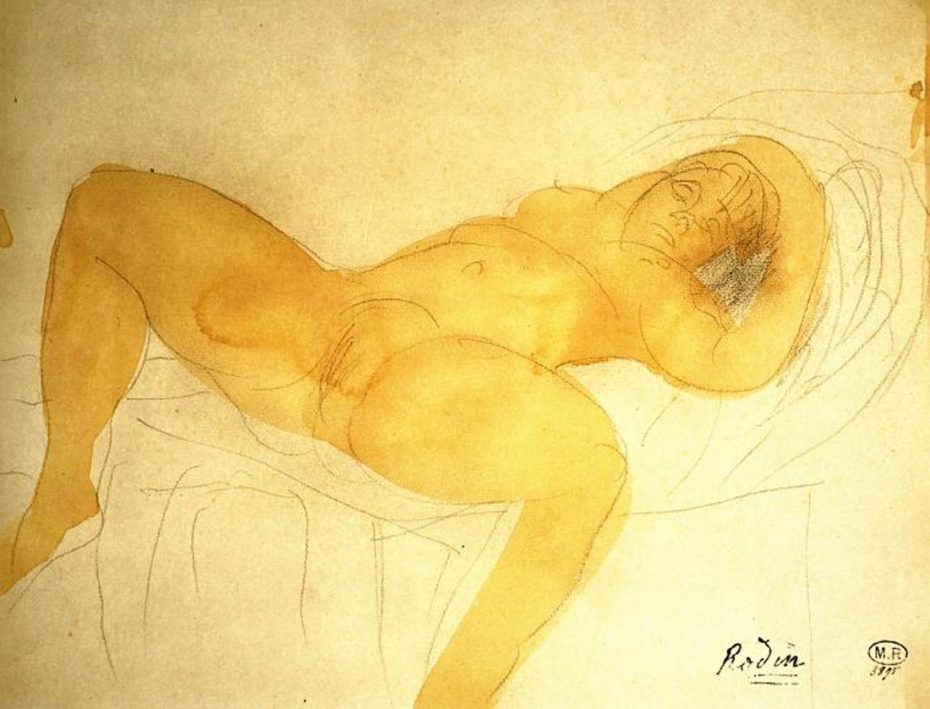

When critics eventually declared that the Photo-Secessionists had won the battle to gain respect in the realm of fine arts, Stieglitz decided to push the boundaries further. He continued planning shows with friends and talents from abroad, namely, one of his old pals back in Paris, August Rodin.

We best know the French artist for his sculptures, but Stieglitz found his erotic drawings were just the ticket for his next show. It was the first time his drawings were ever shown in the States. “They are not the sort of thing to offer to public view,” wrote one critic, “even in a gallery”. If the gallery’s first few years raised critics’ eyebrows, Rodin’s beautiful, “unsightly”, and dirty Rodins hiding the Midtown flat made them slack-jawed. But in 1908, a room full of Rodin was no match for New York’s rising rents. Soon after the show finished, the apartment’s rent doubled in the midst of an economic downturn and Stieglitz was forced to close his photo gallery.

But the altruistic Alfred Stieglitz always had a good circle of friends to turn to. Paul Haviland was a wealthy Harvard grad who’d bought a Rodin drawing from the recent show at Alfred’s gallery, and when he learned of its closure, offered Stieglitz enough money to sign a three-year lease on a space right across the hall from the old gallery. Stieglitz baptised the newest incarnation of the gallery simply “291”, where he would courageously display the works of controversial, unknown artists, and bring modern art to America.

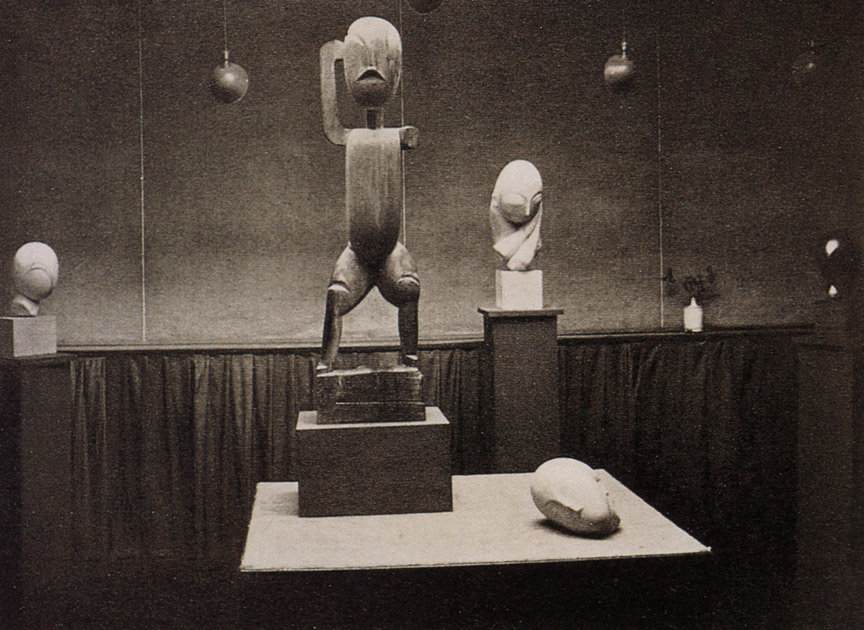

A young 18 year-old Man Ray would frequently spend his lunch breaks at 291, soaking it all in on the top floor of the humble Midtown building, behind an inconspicuous door marked by a sun-disk emblem. “The gray walls of the little gallery [were] always pregnant” with something new and exciting,” he wrote. “Cézanne the naturalist; Picasso the mystic realist; Matisse of large charms and Chinese refinement; Brancusi the divine machinist; Rodin the illusionist…”

291 was the only gallery in the country that was promoting modern art as we know it today. Photo-Secessionist Anne Brigman (aka the woman who invented the art of the selfie) wrote at length about the magical experience of finding 291 for the first time. Ascending into the little attic space, despite “its gray walls and simple hangings” was like walking into heaven. “It was one of my gifts of the gods, that I met in those little rooms … those pictures! I couldn’t believe my eyes – what did they mean? It was as though I had come from or gone to another planet”.

The critic Roland Rood totally lost track of time inside, writing, “I had forgotten that it was evening, and that there must be some kind of light. I had never seen the series of beautiful electric lights that by their quality and disposition gave such a natural illumination that you did not notice them.” To our eyes, the surviving snapshots of the space may seem rather ordinary. But this wasn’t just a gallery. It was a temple.

pixelsniper

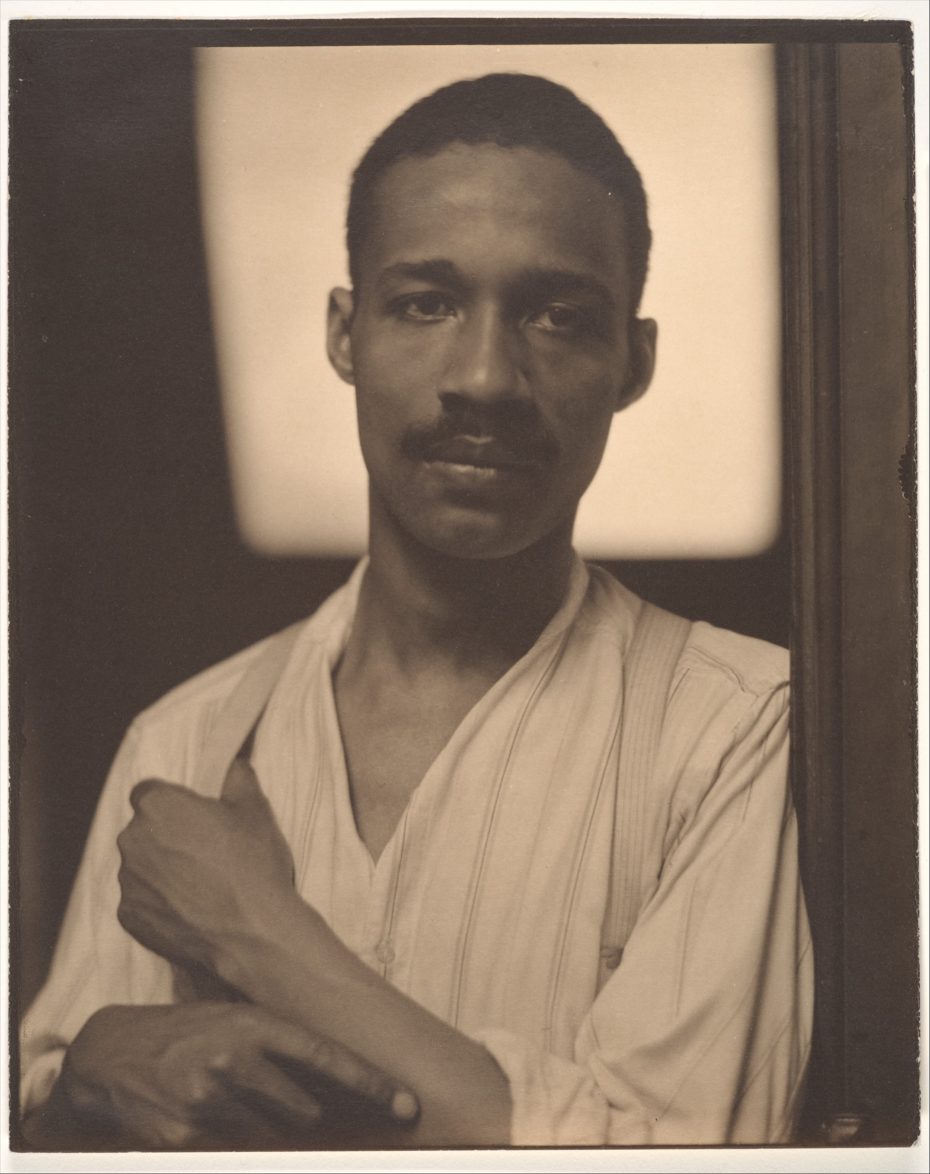

It wasn’t only the cultured elite and Greenwich Village bohemians that had their world’s turned upside down by 291. Operating the elevator in the building was a West Indian man by the name of Hodge Kirnon, who became the symbolic gatekeeper of sorts to artistic enlightenment.

The critic Paul Rosenfeld described his journey up the “rickety elevator” and into a “house of God”, this unsuspecting place that hovered above the daily grind of Midtown with images that took the world by storm. By escorting the gallery’s visitors, its critics, and its provocative modern art up and down that building, Kirnon, had been a true fellow passenger on the momentous trip. The humble “elevator boy” would later find a career as a noted scholar, historian and Harlem freethinker.

“The numbers 2-9-1 may have seemed to be just “numerals,” wrote Anne Brigman, “[but] have grown to mean more than numerals.” They were a code for breaking convention, and always in good company.

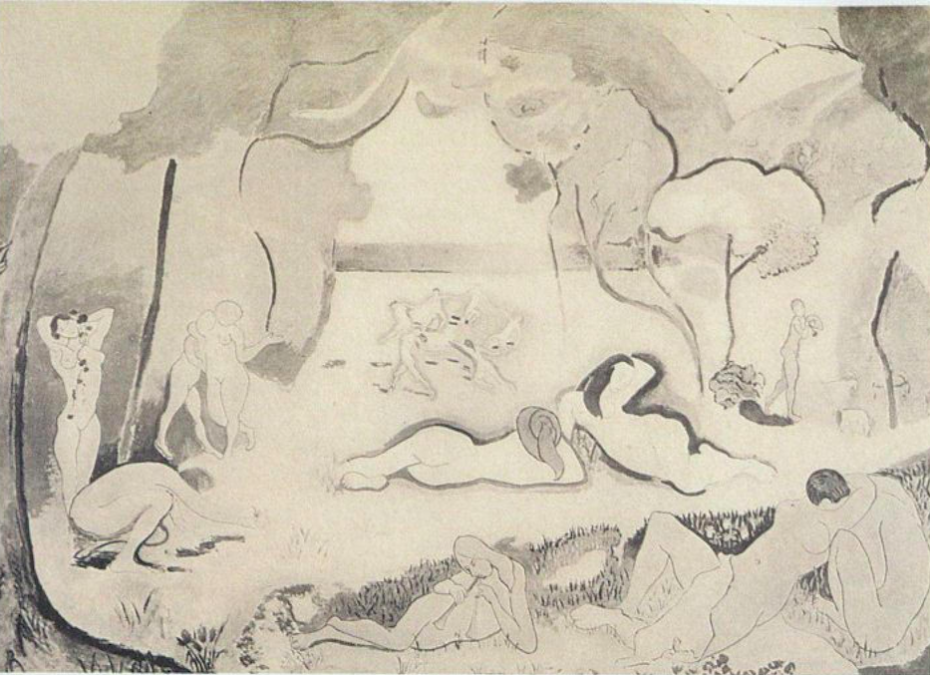

In 1908, Gallery 291 brought in prints of a French artist, then unknown across the Atlantic, for a solo show – Matisse’s first American exhibit. “Here was the work of a new man,” said an elated Steiglitz, “with new ideas – a very anarchist, it seemed, in art. The exhibition led to many heated controversies; it proved stimulating”. In 1910 Cézanne followed suite, and in 1911, Picasso. Stieglitz delighted in saying that while the critics called the Spaniard’s works, “the gibberings of a lunatic,” he thought they were “as perfect as a Bach fugue”.

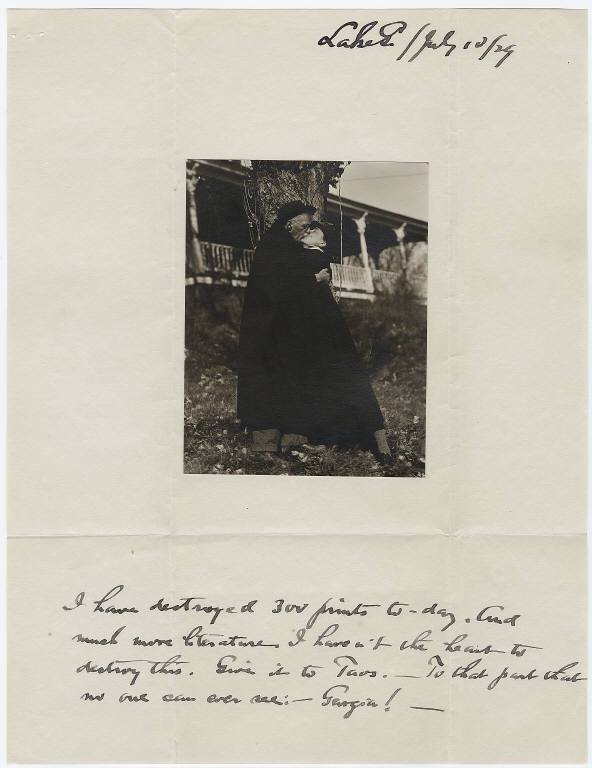

It’s near the epilogue of Stieglitz’s glory years that we come across the artist who was, for many, his most thrilling find – and the greatest love of his life: Georgia O’Keeffe. Now at this point, O’Keeffe was a relatively unknown, Midwestern art school teacher. But in 1916, a New York City friend had shown Stieglitz O’Keeffe’s charcoal drawings – and he liked what he saw so much, that he gave O’Keeffe her first solo-show (one of the last shows at 291).

What began as a professional correspondence between the two soon blossomed into a romance. Their letters up until 1946 totalled over 25,000 pages, with some stretching over 40-pages long. “How I wanted to photograph you — the hands — the mouth — & eyes — & the enveloped in black body,” he wrote her in 1917, ” the touch of white — & the throat — but I didn’t want to break into your time.”

Her works were the perfect bookend to his career, and one of the last grand offerings of 291 to the world, which had hosted 61 exhibits in less than a decade and become a vertiable mecca for modern art. But you’d never know it from the looks of 291 today as the very building itself has been wiped clean from Manhattan.

The decline of the gallery came with the mounting tensions of war with Germany. Suddenly, Stieglitz found that having one foot in Europe – Germany, in particular – and the other in America was divisive amongst his friendship group; he didn’t sympathise with the German war efforts, but he couldn’t deny his ties with, or affection for, the country of his heritage.

Come 1917, just two months after the US declared war, the gallery closed up shop forever. Until that time, Gallery 291 had continued to outdo itself with every new exhibition. One thing that never changed was the intimacy of the gallery, which Stieglitz felt was crucial to the success of a show.

“I have found in “291” a spirit which fosters liberty,” wrote the building’s elevator operator Hodge Kirnon. “[It] defines no methods, never pretends to know, never condemns, but always encourages those who are daring enough to be intrepid”.

So here’s to starting movements out of tiny apartments. Here’s to being curious and finding treasure, beauty and inspiration in the most unlikely places. And here’s to the words of the eternal godfather of 291, the man who dared to show Picasso in a 5th floor attic: “Give every man who claims to have a message for the world a chance of being heard.”