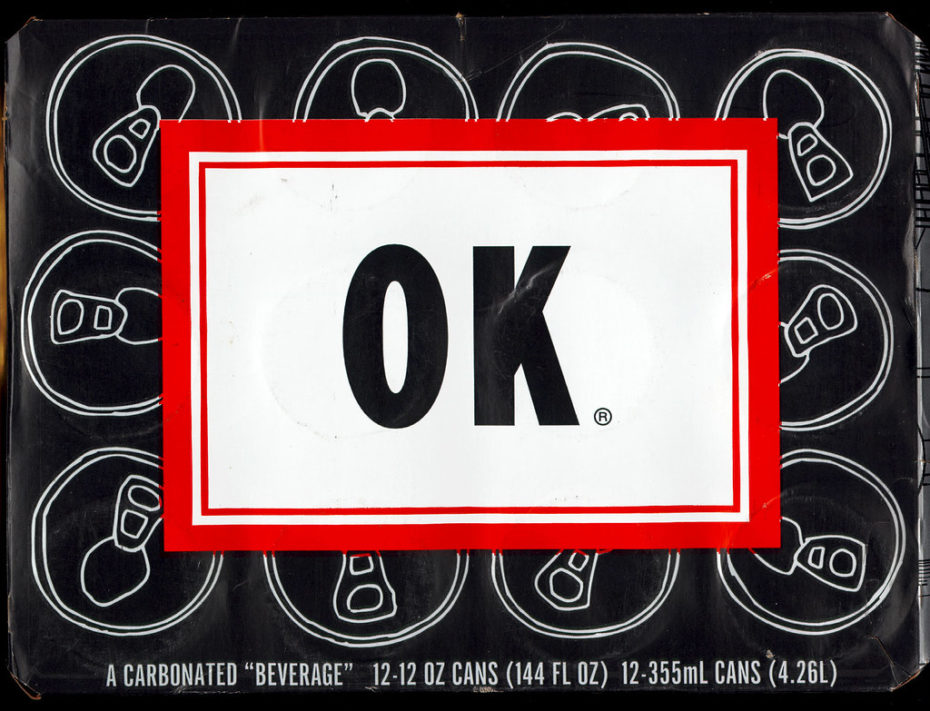

No one quite knew what to do with Generation X (born from the late 1960s to the early ’80s), but marketers were especially stumped at how they could appeal to this new, generation of globalisation that was disillusioned with the status quo. The heart of the matter was, and remains, incredibly subversive – a challenge to dive head-first into a risky marketing ploy that raises eyebrows even today: could such a blatant anti-advertising message be profitably used by advertisers? In 1993, Coca-Cola tried with a new, intentionally drab soft drink called OK Soda. “It underpromises,” Coke’s projects manager said, “It doesn’t say, ‘This is the next great thing.’ It’s the flip side of over-claiming.” It was supposed to be the marketing world’s greatest reverse psychology triumph, a mastery of consumerism over postmodern disillusion. But things didn’t quite work out at planned, and retracing the lifespan of OK Soda is reveals not only an embarrassing snapshot from Coke’s past, but a window into what consumers really (don’t) want to hear.

Let’s dive head first into a commercial, shall we?

When they were looking to introduce a new beverage, Coca-Cola’s special projects manager Brian Lanahan told Time Magazine that they chose the name “OK” because it didn’t sensationalise the product. It spoke the truth, even if the truth wasn’t pretty – which is what the 1990s were all about. The drink’s slogan was, “Everything is going to be OK.” Not great, and not even alright. Just, “OK”. If the ’80s was one big, cocaine-fuelled party, this was its inevitable hangover. Grunge music and The Matrix reigned supreme. The internet was finding its footing, while still scaring the sh*t out of everyone, even king of weird, David Bowie, who quite elegantly summed up what everyone was feeling in a 1999 interview with the BBC. “It’s an alien life force,” he said, “I don’t even think we’ve seen the tip of the iceberg. I think we’re on the cusp of something exhilarating and terrifying.”

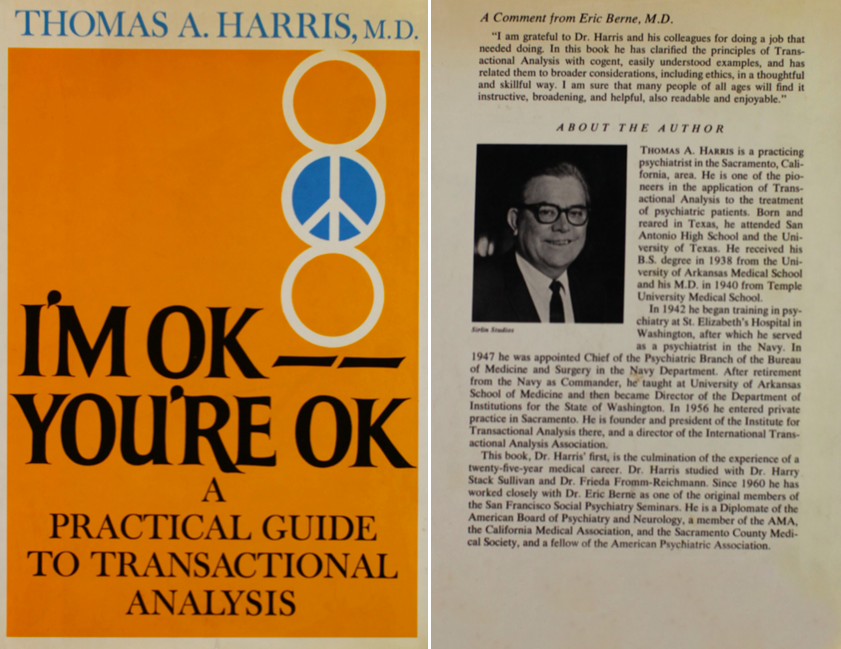

The name of the product was also deceptively simple. Not only were “OK” and “Soda” rather banal words, but statistics had shown that they were also the most widely recognised on an international level. Inspiration was also found in the hit 1967 self-help book, I’m OK – You’re OK, by Thomas Anthony Harris, which said most of our anxiety stems from feelings of defencelessness in childhood, in which we internalise the idea that “I’m Not OK-You’re OK” that he broke down into “4 Life Positions”:

- I’m Not OK, You’re OK

- I’m Not OK, You’re Not OK

- I’m OK, You’re Not OK

- I’m OK, You’re OK

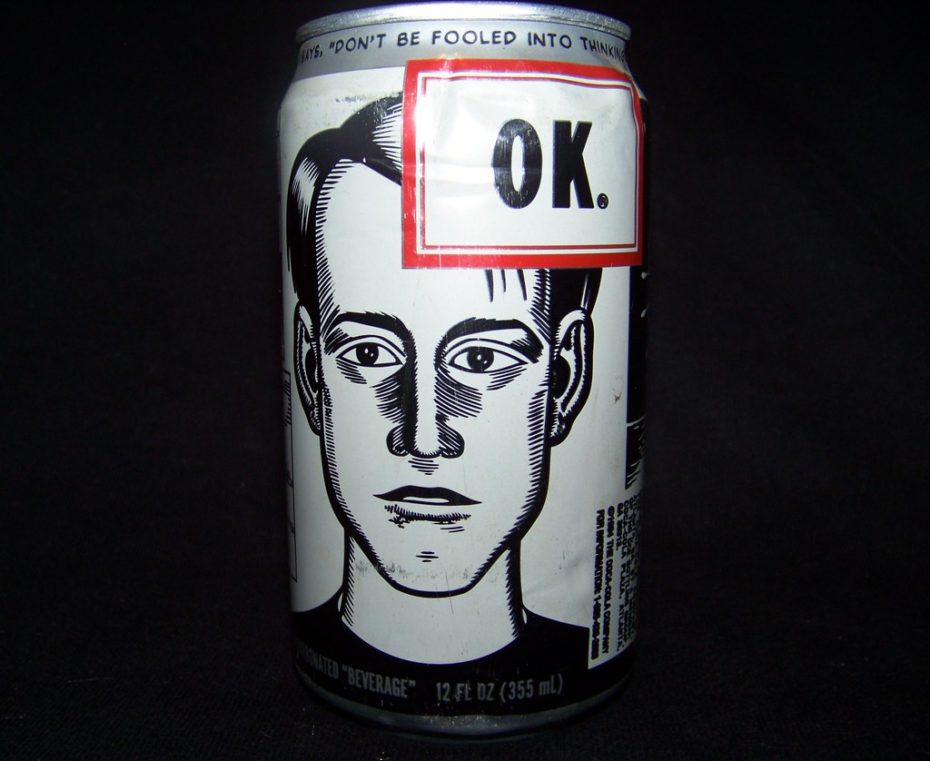

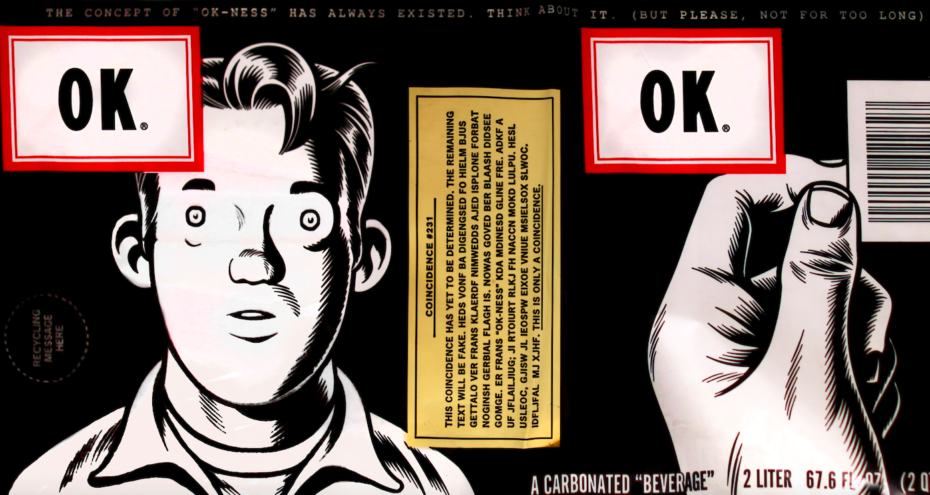

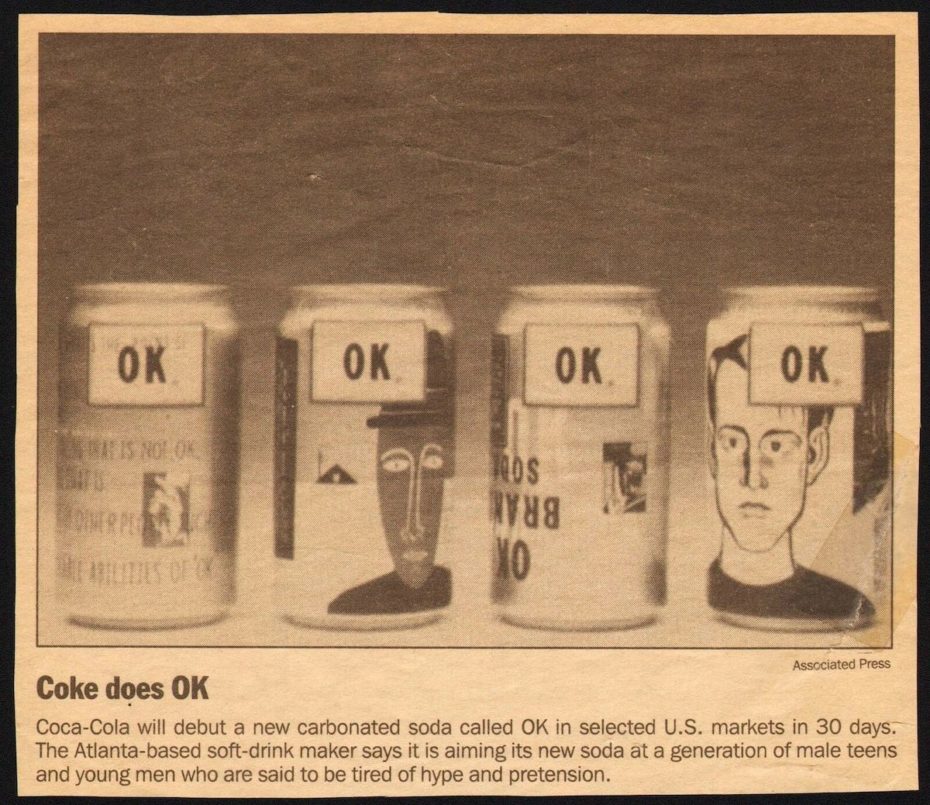

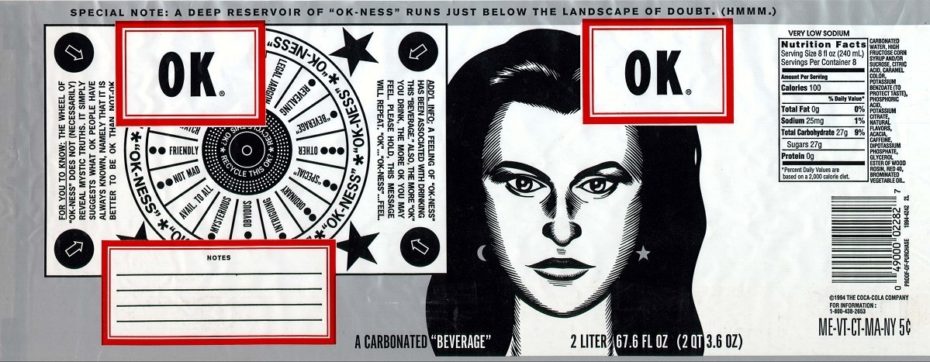

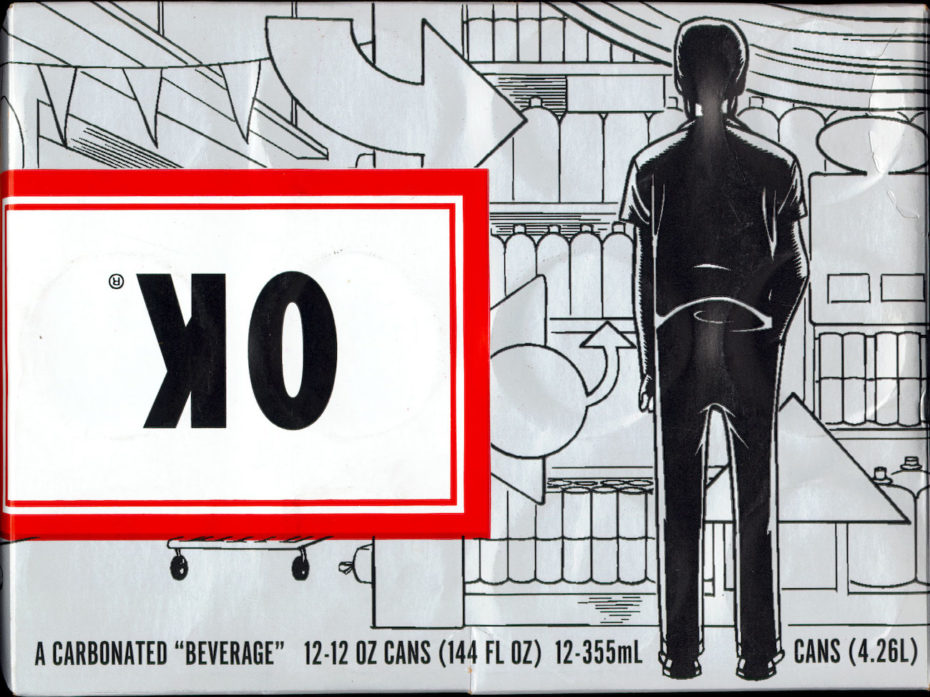

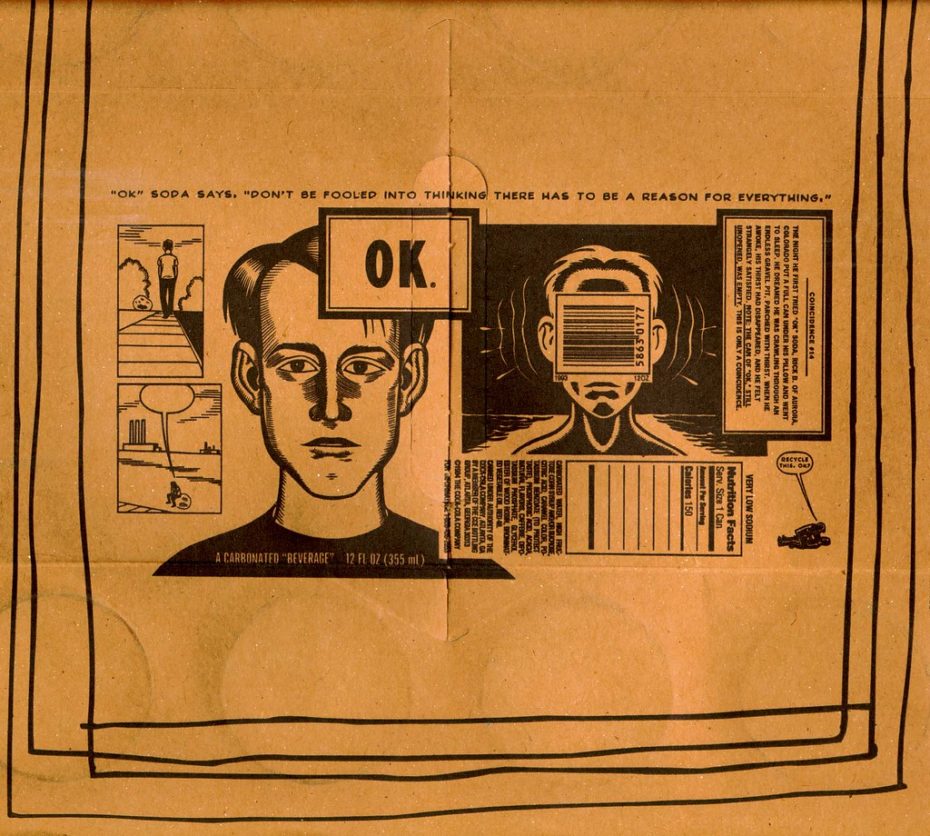

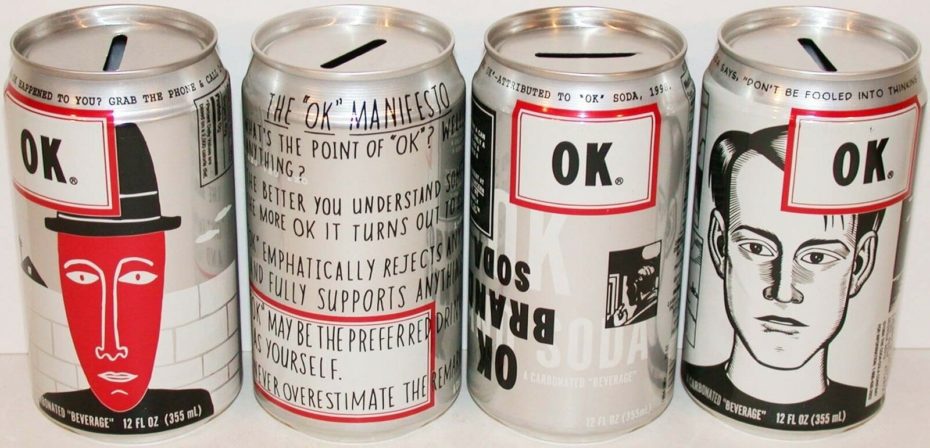

Thus OK Soda was burst onto the market, and unlike the bottomless well of optimism found in the flower power generation, tapped into the intentional apathy and skepticism – think Julia Stiles in Ten Things I Hate About You — that signalled Gen X’s way of expressing hatred for The Man™. The cans were dressed in the drawings of legendary alt cartoonists Charles Burns (Black Hole 1995-2005) and Daniel Clowes (Ghost World, 1993-97), the latter of which said he used Charles Manson’s face as a model for one of his designs.

It also had its own lengthy manifesto, reminiscent of Harris’ book:

- What’s the point of OK? Well, what’s the point of anything?

- OK Soda emphatically rejects anything that is not OK, and fully supports anything that is.

- The better you understand something, the more OK it turns out to be.

- OK Soda says, “Don’t be fooled into thinking there has to be a reason for everything.”

- OK Soda reveals the surprising truth about people and situations.

- OK Soda does not subscribe to any religion, or endorse any political party, or do anything other than feel OK.

- There is no real secret to feeling OK.

- OK Soda may be the preferred drink of other people such as yourself.

- Never overestimate the remarkable abilities of “OK” brand soda.

- Please wake up every morning knowing that things are going to be OK.

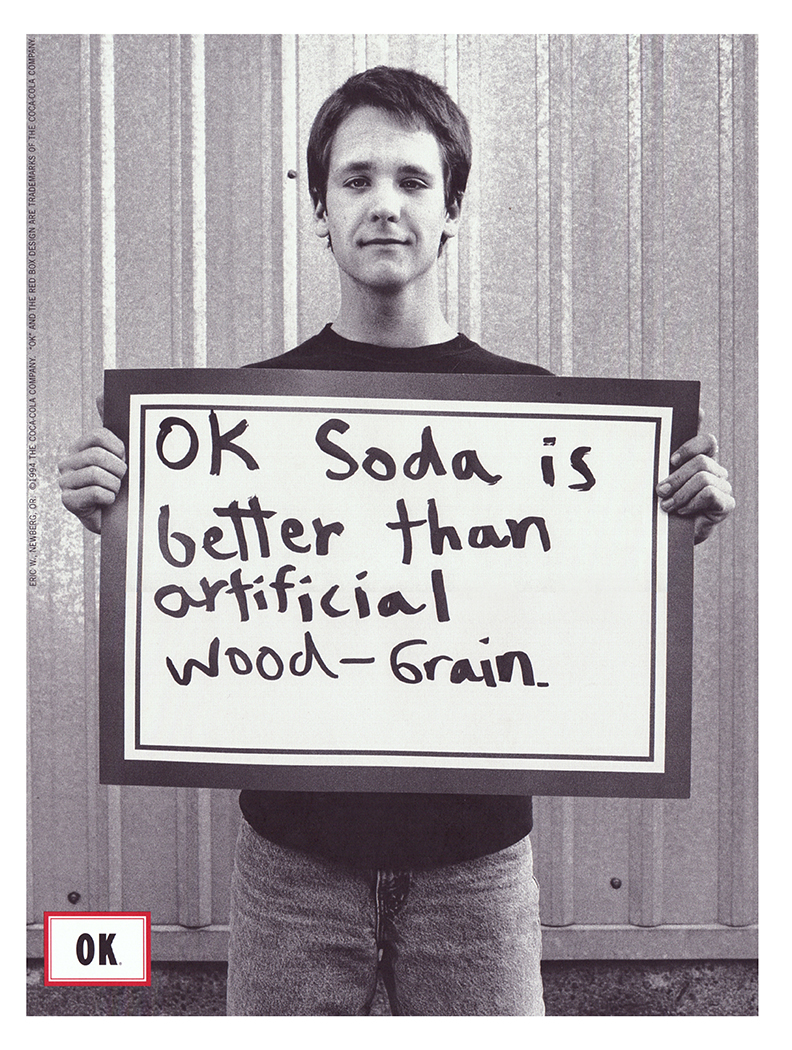

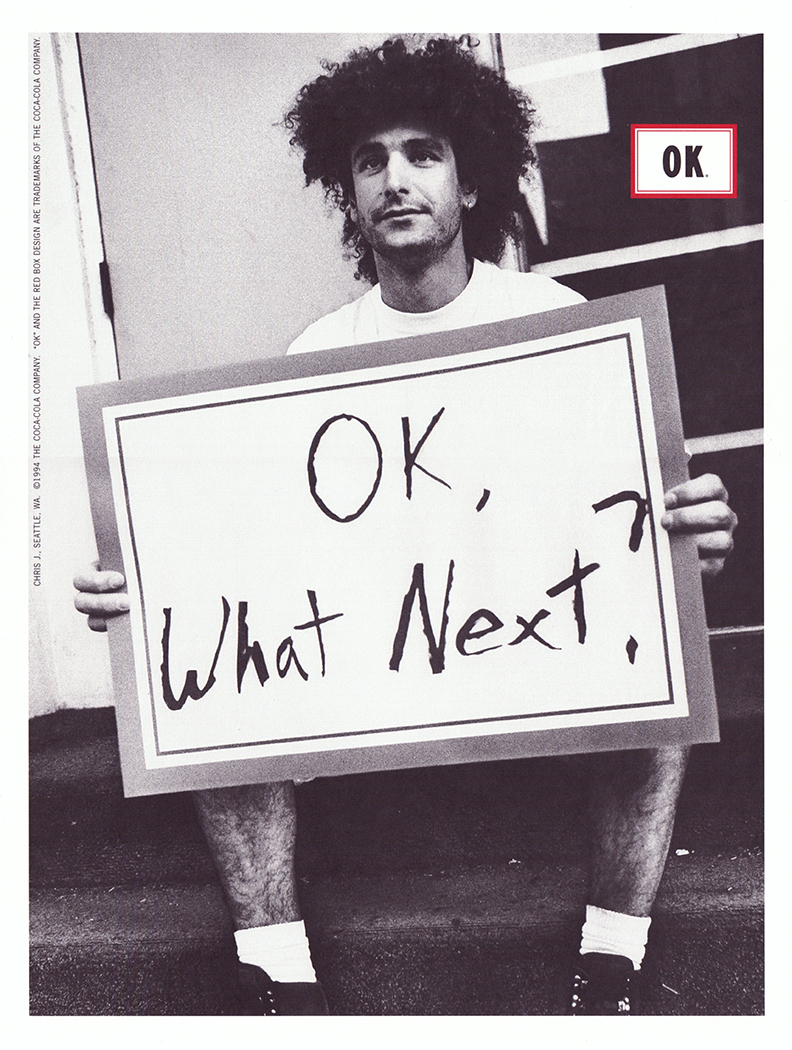

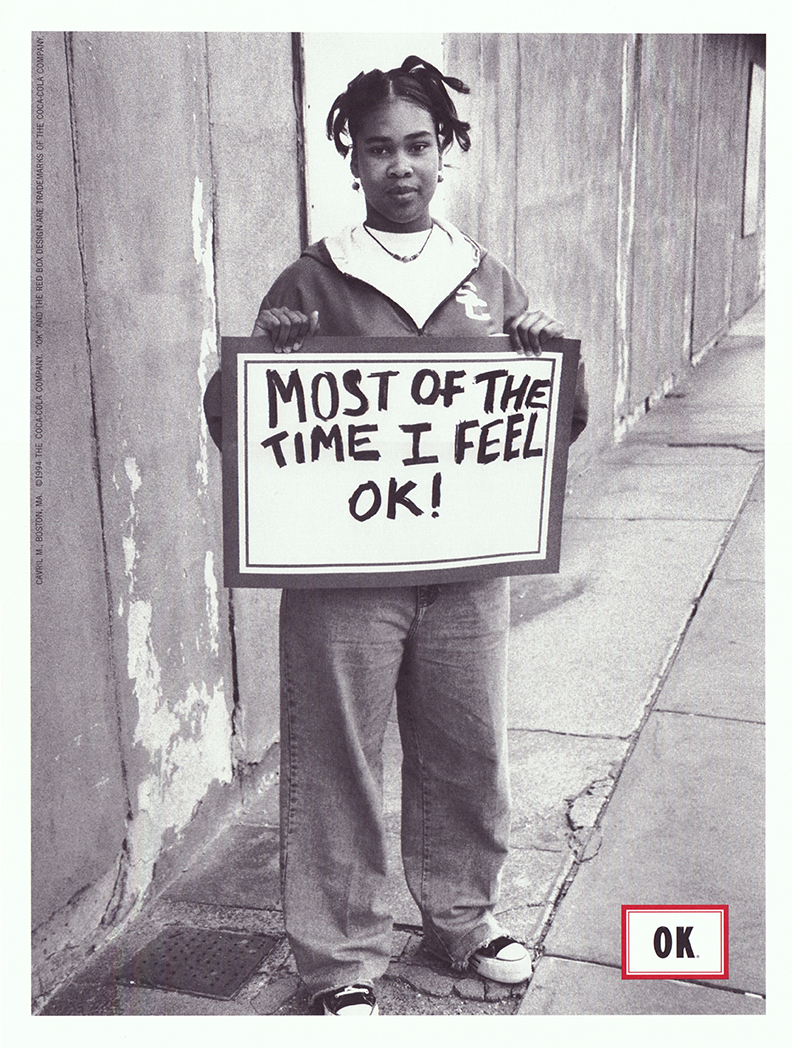

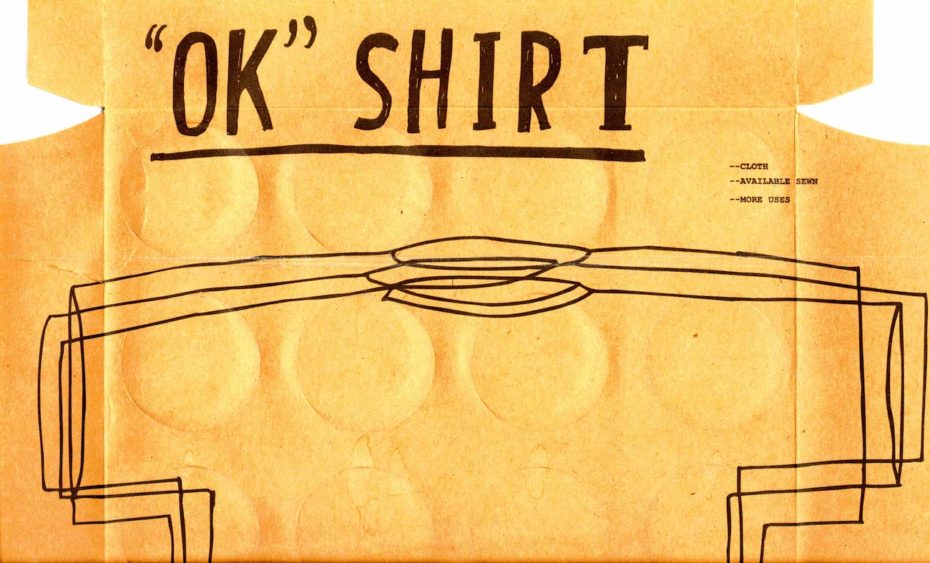

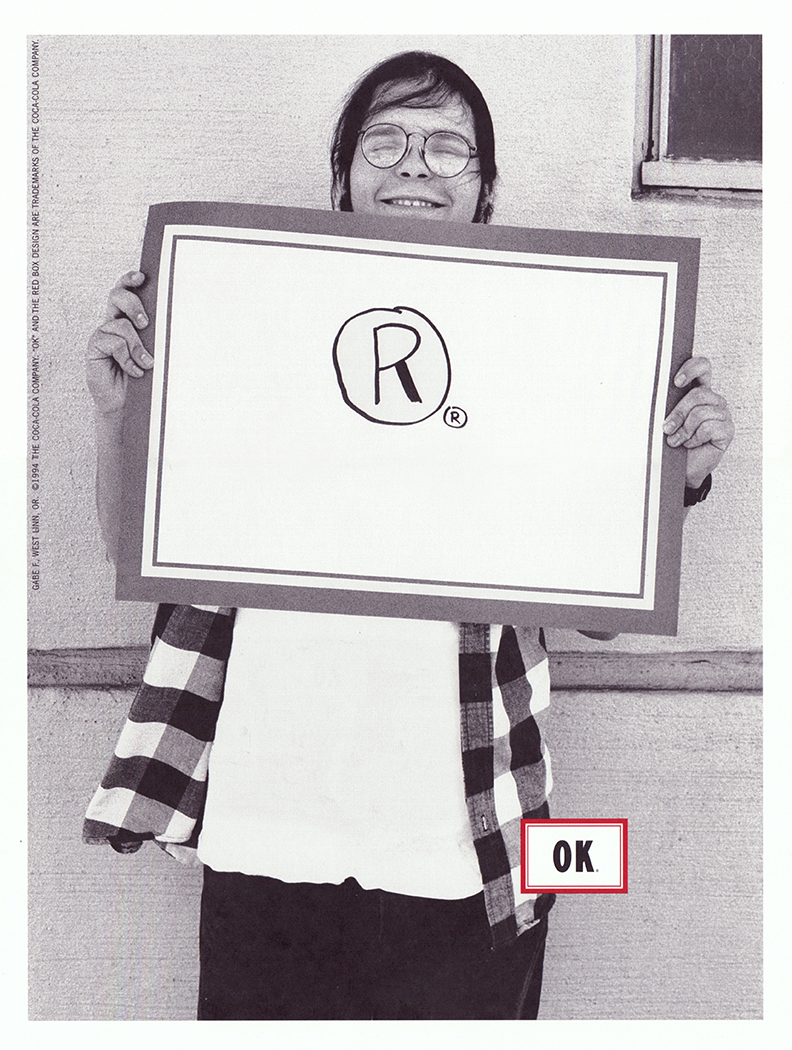

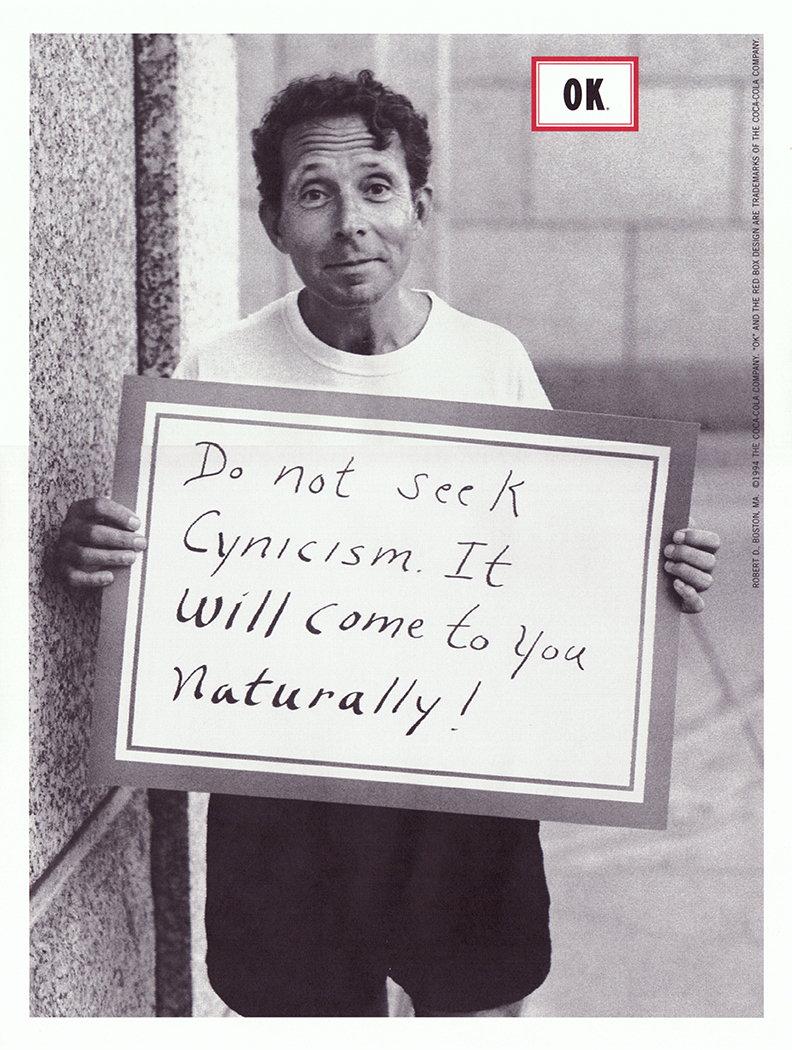

There was a number (1-800-I-FEEL-OK) you could dial to spill your own thoughts, and cryptic coincidental texts like the following, called “Coincidence #3”: “James S. of Little Rock, Arkansas drank a can of “OK” and found he could not only dangle a spoon from the end of his nose, but also a fork, and after several cans, sometimes a knife as well.” Consumers could also win the occasional “prize can” with a peel-able top revealing free merchandise, or find notes in their twelve-packs for free t-shirts reading, “OK Soda says, ‘Don’t be fooled into thinking there has to be a reason for everything'”. Magazine spreads also featured pictures of consumers with their own handmade, “OK” signs.

To say things went poorly would be an understatement – the drink was pulled from shelves by 1995 after just 2 years because it failed to sell. For one, it was a crummy product, and aptly marketed as tasting like “carbonated sap”. Most importantly, Coke’s marketing man, Sergio Zyman, had simply underestimated Americans’ thirst for optimism. When it comes to commercials, traces of postmodernism can come across as loveable (i.e. when a commercial self-references itself, or an actor breaks the 4th wall), but engulfing an entire product in it proved excessive – especially because that postmodernism struck grim tone, rather than, say, the fun Dos Equis guy.

Decades later, OK Soda’s story endures as one of the biggest advertising fails ever – but it was also pretty brazen. Innovative marketing teams have to have one foot in the trending present, while anticipating what consumers are looking for on the horizon (more easily said than done). Luckily, OK Soda’s cult following has aged well, and today its empty cans go for a small fortune for collectors (ex. These four on eBay are going for $249.99).

What do you think of OK Soda? Would the campaign speak better to consumers today?