Where there’s a will, there’s a way — but for pilot Jacqueline Cochrane, there had to be even more. “To live without risk, for me,” she said, “would be tantamount to death.” One of the biggest risks of her career was pioneering the US organisation, WASPS (Women Airforce Service Pilots). In the heat of WWII, the WASPS proved that not only could women fly, but they could fly furiously well. They trained under the same rigorous conditions as their male counterparts under the hot sun of Sweetwater, Texas, piloting combat planes, ferry aircrafts – they even flew as live practice targets for the men – but were never allowed to enter combat. In fact, until the 1970s, they weren’t even granted military status. Only in recent years has credit been given to these unsung sheroes of the skies, who proved that “Anything you can do, I can do better – and in lipstick.”

America was embarrassingly late to the game. Women in England began ferrying planes for the war effort three years prior. As early as 1914, Russia’s Princess Eugenie Shakovskaya served as an artillery and reconnaissance pilot, and women in general filled not only auxiliary roles, but jobs as snipers, machine gunners, and tank crew members in the USSR. Cochrane wrote the First Lady in 1939 to propose that women pilots take over some of the domestic, non-combative duties as men. Everyone, after all, was doing their bit for the war effort, and the initiative would free up more male pilots for service on the front lines. Eleanor Roosevelt agreed, and Cochrane flew a ferry bomber to the UK to gain some media buzz going about the notion of women taking to the skies.

But the WASP program wasn’t off the ground yet. It resulted from the snowballing of various efforts, like the WAFS (The Women’s Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron), which formed after Cochrane and fellow pilot Nancy Love successfully submitted proposals to Congress for a women’s flight program. From there, the WFTD (Women’s Flying Training Detachment) organisation was created, and finally, in 1943, the two programs combined to form the ultimate super-program: the WASPS.

“They’re civilians, but under Army discipline,” says the narrator of a 1940s TV-spot on the WASPS, which cheerfully points out that their insignia, “a little flying lady,” was designed by Walt Disney, and initially a creature from a Roald Dahl book:

SDASM Archives

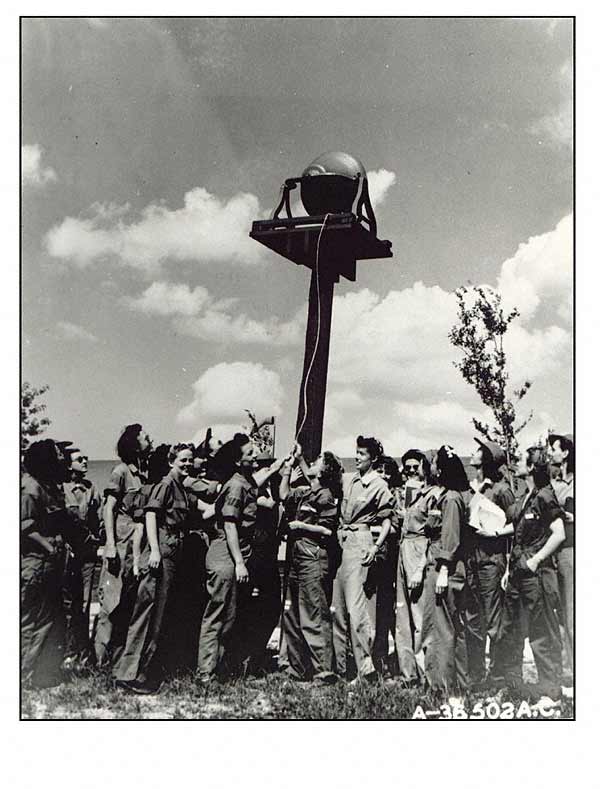

“There’s a bill of congress to bring the girls into the regular airforce,” the narrator continues, “but in the meantime, they must endure the same rigorous training given any soldier. Little girls flying big planes need not only the brain power, but the physical strength.” For the public, the women were a marvel. They graced the covers of magazines, and became beacons of “doing one’s bit” for the war effort by filling the shoes of the men.

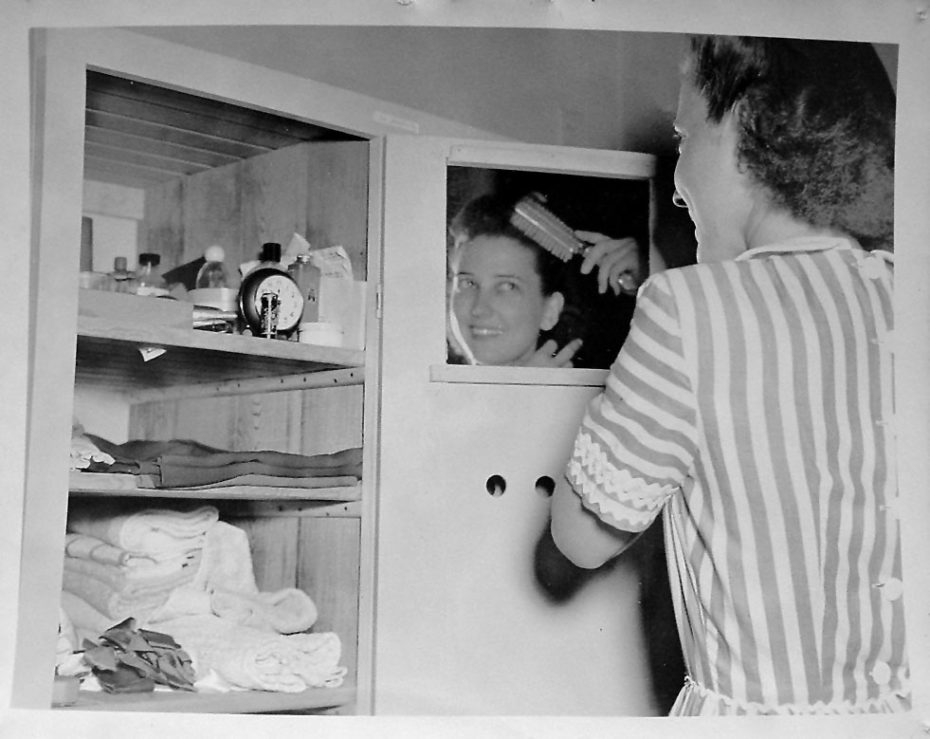

But that was the caveat. Every success the women had was coloured with a sense of novelty, of filling another man’s shoes when, in truth, they were taking to the skies in their own heels. Head to the WASP museum in Sweetwater today, and you’ll hear stories of how the women reapplied their red lipstick post-flight, before even stepping out of the cockpit, to show their male instructors that they couldn’t be shaken.

A young man who’d never set foot in the sky could walk in to the air force and be trained, but any women who were hired as WASPS had to have serious aviation experience: out of the 25,000 who applied, just over 1,000 made it in. You had to want it, bad. Above all, the training equipment was old, and dangerous. Pilot Byrd Granger said the women looked like “a raggle-taggle crowd in a rainbow of rumpled clothing” when they set off to train, which may sound spunky, but the lack of resources for safe training became fatal when pilots like Margaret Oldenburg and Mabel Virginia Rawlinson died due to the shoddy state of their aircrafts.

The WASPS weren’t just seat warmers for combat pilots, they were performing seriously dangerous tasks, like trailer targets for practicing male pilots who sometimes didn’t realise that you didn’t need to gun down the entire plane. Not that that scared the WASPS. “I thought, ‘You know what? I’m not going until I see flame. When I see actual fire, why, then I’ll jump'” former pilot Margaret Phelan Taylor told NPR in 2010, “I was never scared. My husband used to say, ‘It’s pretty hard to scare you.'”

The women flew 80% of all ferrying missions during the war effort, and delivered over 12,000 aircrafts. They’d rise at 6:00am at their Avenger Field base, first for six months of probational training in which they had to learn meteorology, morse corse, and complex physics; map reading, military law, and aircraft mechanics.

SDASM Archives

They had to be between just 21-25 years old, amass 35 hours of solo-flying, and learn all “military courtesies and customs” despite a formal lack of military status. Still, in-training, they were paid $150/month, and once active, $250/month. But if a WASP died during her service, there was no compensation for surviving family members – their remains would’t even be sent home, nor could the US flag adorn their coffin. In total, 38 women were lost in duty.

SDASM Archives

It cost time, money, and eschewing the stigma of swapping the kitchen for the clouds to become a WASP — so when the government stopped the program after the war, it was a serious blow to the female pilots. “As long as they work well,” the promotional video had decreed just years before, “the job of training women pilots will go forward.” It truth, it was more of a, ‘while the men were away, the women could play’ mentality, and once they returned, there was nothing more un-patriotic than letting women “steal their jobs”. In winter of 1944, the program was closed.

Still, many of the WASPs stayed in the skies, if only as flight attendants. Some even volunteered for the Chinese Air Force who were fighting in a war against Japan. But for the most part, their story was slated to fall into legend: they weren’t officially military, but as a military-supported initiative had their files classified as secret for decades to come. It took the 1970s, and the momentum of feminism, to finally see to it that they gained their status; and it wasn’t until Obama’s term that they were reinstated military burial rights and given the Congressional Gold Medal.

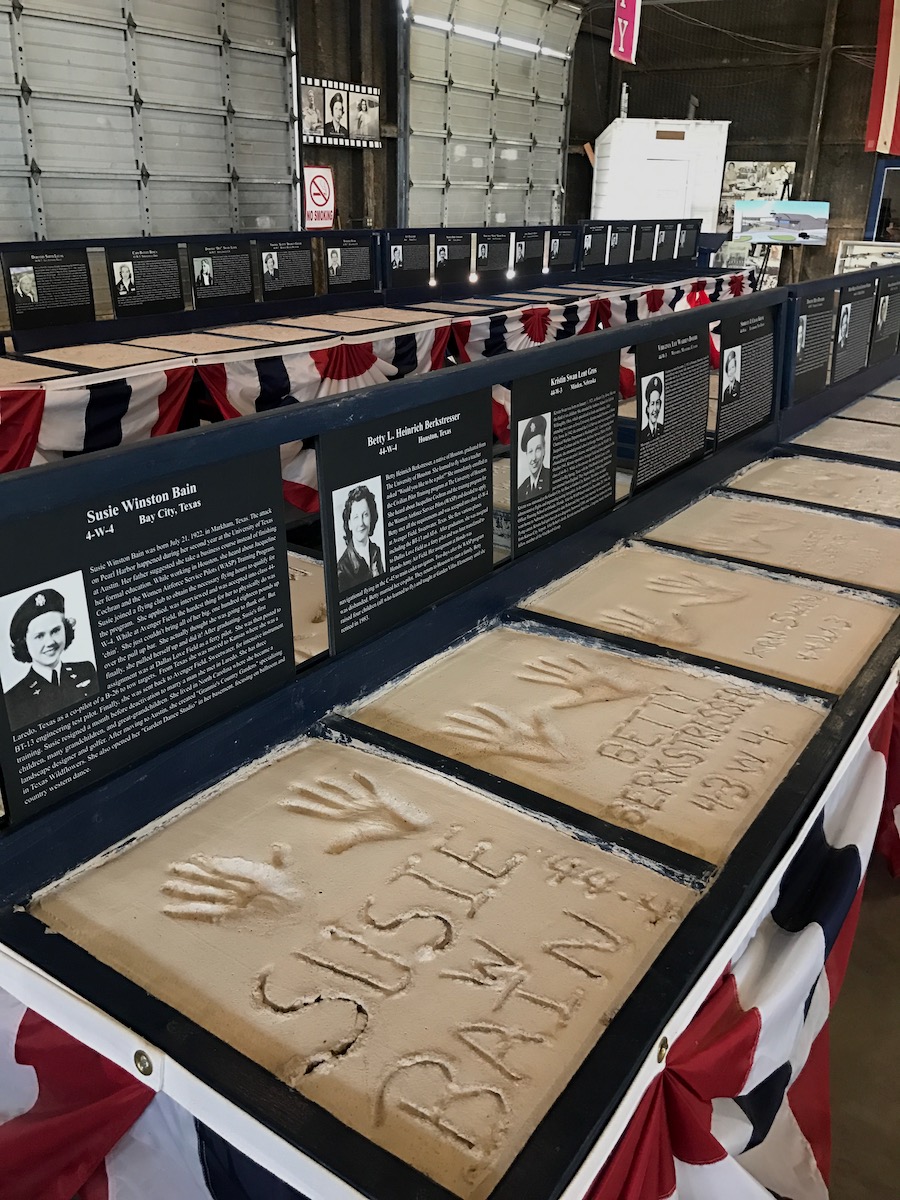

Today, you can head to the WASP headquarters in Sweetwater for yourself — and try and imagine what it must’ve been like to be in one of the greatest invisible troupes of WWII, and walk amongst the handprints of the legendary ladies in a Grauman’s Theater-esque tribute. We sure hope there’s a film in the works about these fearless women…

Learn more about visiting the WASP Museum here.