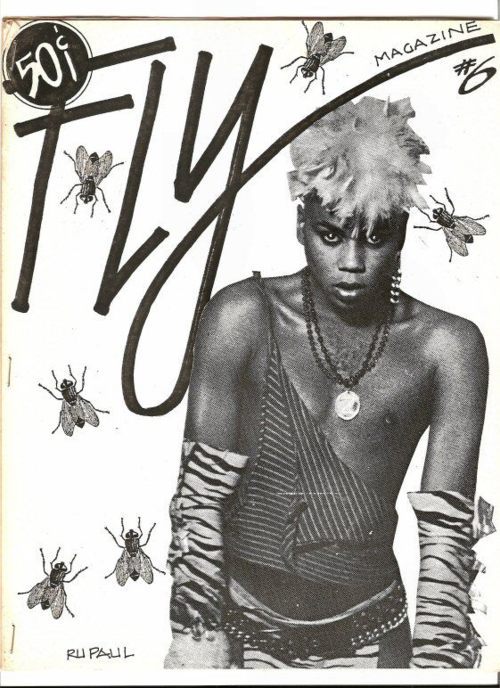

Hoist up your garters and fasten your wigs, because we’re voguing our way back in time to the origins of drag ball extravaganzas: those champagne and lipstick fuelled soirées where drag queens, cross-dressers, and everybody in-between gathered to unfurl their fabulousness in style – and just like on the main stage of the hit TV show competition, RuPaul’s Drag Race, they were taken quite seriously. “The most beautiful costumes are greeted by a sign of the ceremony master with a thundering fanfare,” said the late LGBTQ activist Magnus Hirschfeld (and founder of the world’s first sexology institute), who understood the double function of a drag queen’s dance floor: turning out looks, and turning up social justice. So in prep for this week’s big Drag Race finale, we give you some of history’s grandest balls and non-binary dames. Some identified as queens, others were transvestites, transgender, or just queer, but all of them paved the way for the drag scene we have today. In the words of RuPaul: Gentlemen, start your engines – and may the best woman win.

For as long as humans have been wearing pants, there have been gender-bending performers and community figures. Ancient Egyptians actually had three genders, and they all wore makeup (but we digress). The point is, by the late-17th and early-18th century we really start to see the roots of a unique, queer ball scene. The Sun King encouraged cross-dressing at his parties, and documents from the 1620s recall Portuguese faschonos, aka Baroque drag queens, throwing wild Gaia Lisboa (gay Lisbon) parties. Spain of course had carnival, which not only spilled onto the streets in broad daylight, but let members of the royal cabinet participate in drag. And then, there was Berlin…

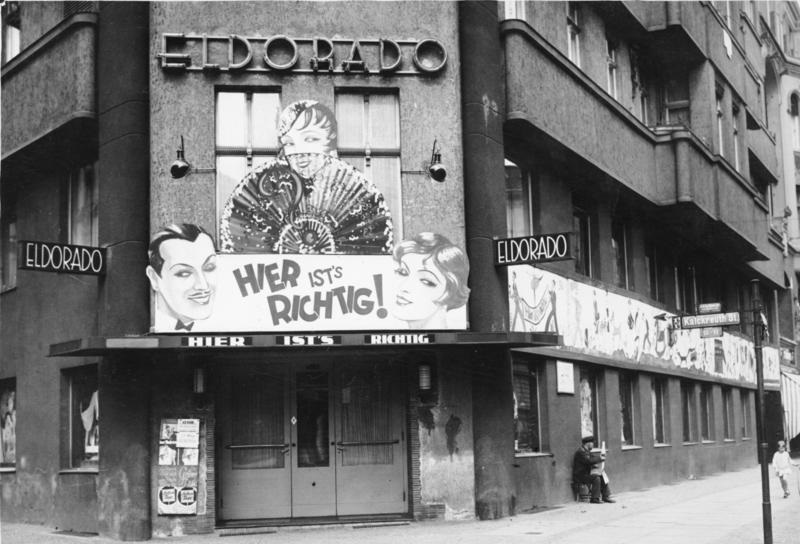

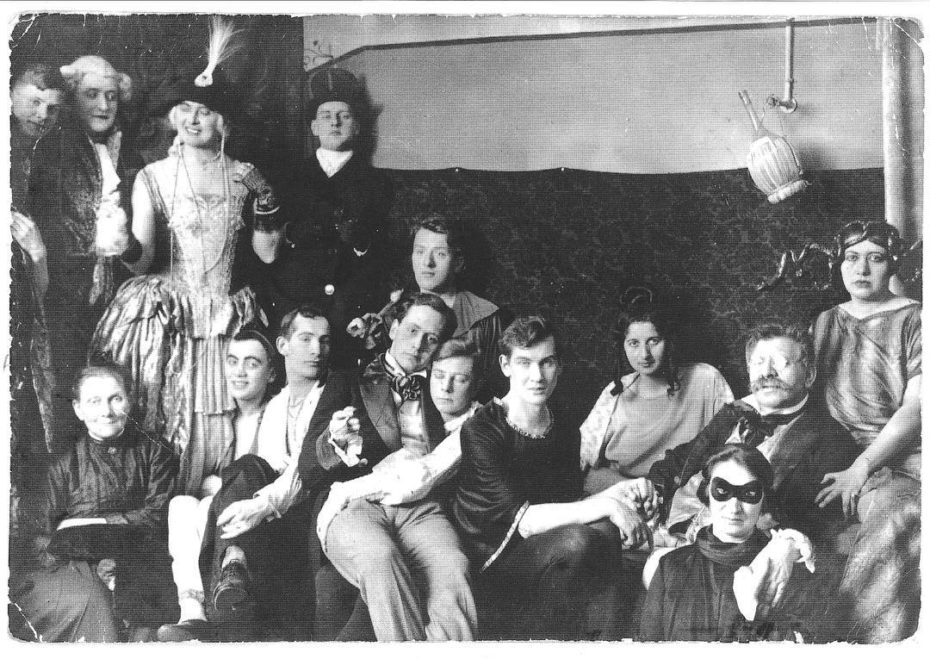

In Berlin, the sheer number of cross-dressing balls that occurred in the late-19th century up into the 1930s was astounding. Known as Urningsballs or Tuntenballs, they were elaborate gatherings that drew crowds of hundreds from all across Europe, despite the fact that it was still illegal to be gay in Germany. These ballrooms became fleeting community spaces for “uranians” (shorthand for those believed to be of a third sex, with a female psyche in a male body), and held court at the Dresdner Straße, Deutscher Kaiser, Dresdener Casino, the El Dorado, and other sprawling venues.

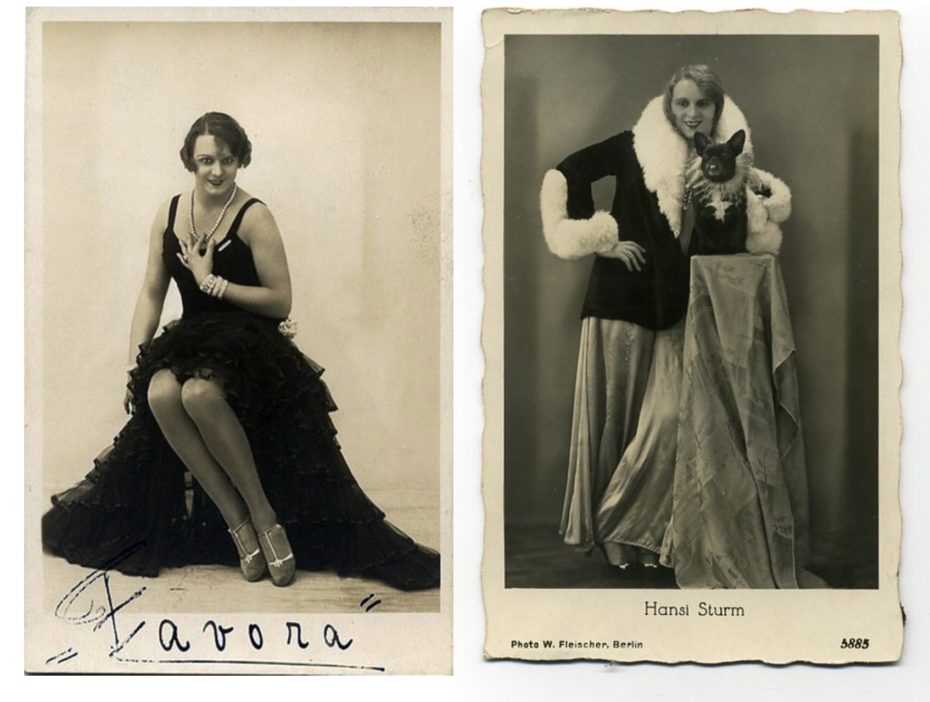

One of the stars in this scene was Hansi Sturm, who became quite the celebrity in Berlin, well-loved both within and outside of the ballroom scene and his postcards were widely distributed. After dark, the married father of two became the singing and dancing ‘Miss Eldorado’, best known for his entertainment act that finished with him throwing his fake breasts into the audience.

“During the high season from October to Easter, these balls are held several times a week, often even several a night,” wrote Hirschfeld, who also loved and participated in the balls, “[men] come in fantastical costumes, a large part in evening gowns, some in simple, others in very elaborate toilets. I saw a South American man in a robe from Paris, its price had to be over 2,000 francs.” Their period-inspired threads were often so heavy that they wouldn’t just sweep the floor – they’d drag. You see where we’re going with this, right?

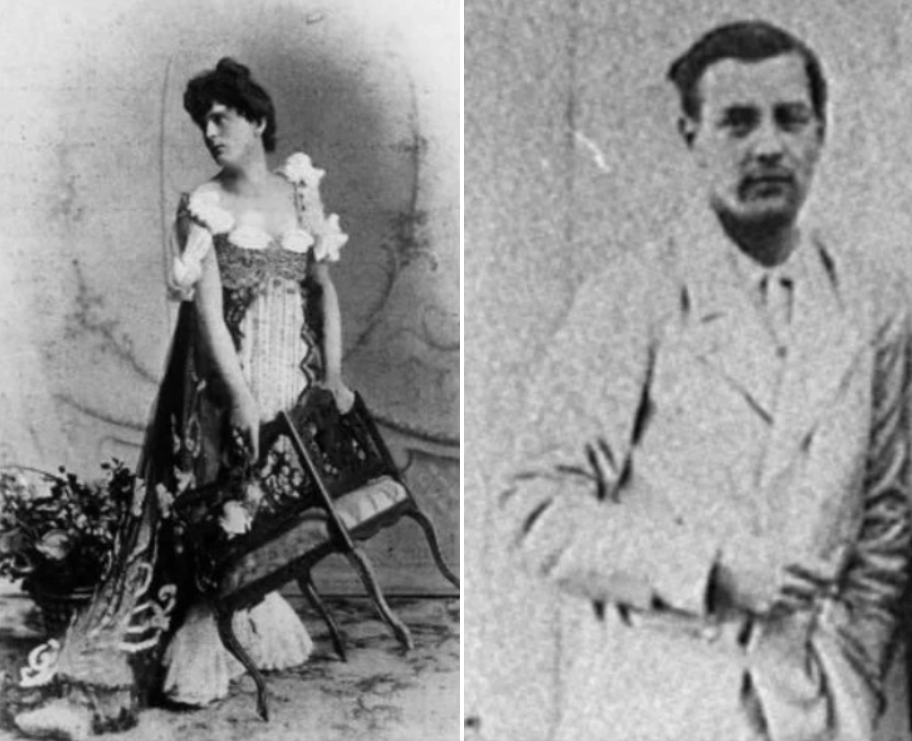

It was actually considered embarrassingly poor form to turn up at a ball without going all-out in your drag – even a trace of facial hair was, as Hirschfeld said, a “Most distasteful and repulsive [sight]…[these] gentlemen that, in spite of coming ‘as women’, keep their stately mustaches or even a full-beard.” At least he could count on Hermann von Teschenberg, a female transvestite, pal of Oscar Wilde, and staple of the ball scene to always turn out a full look:

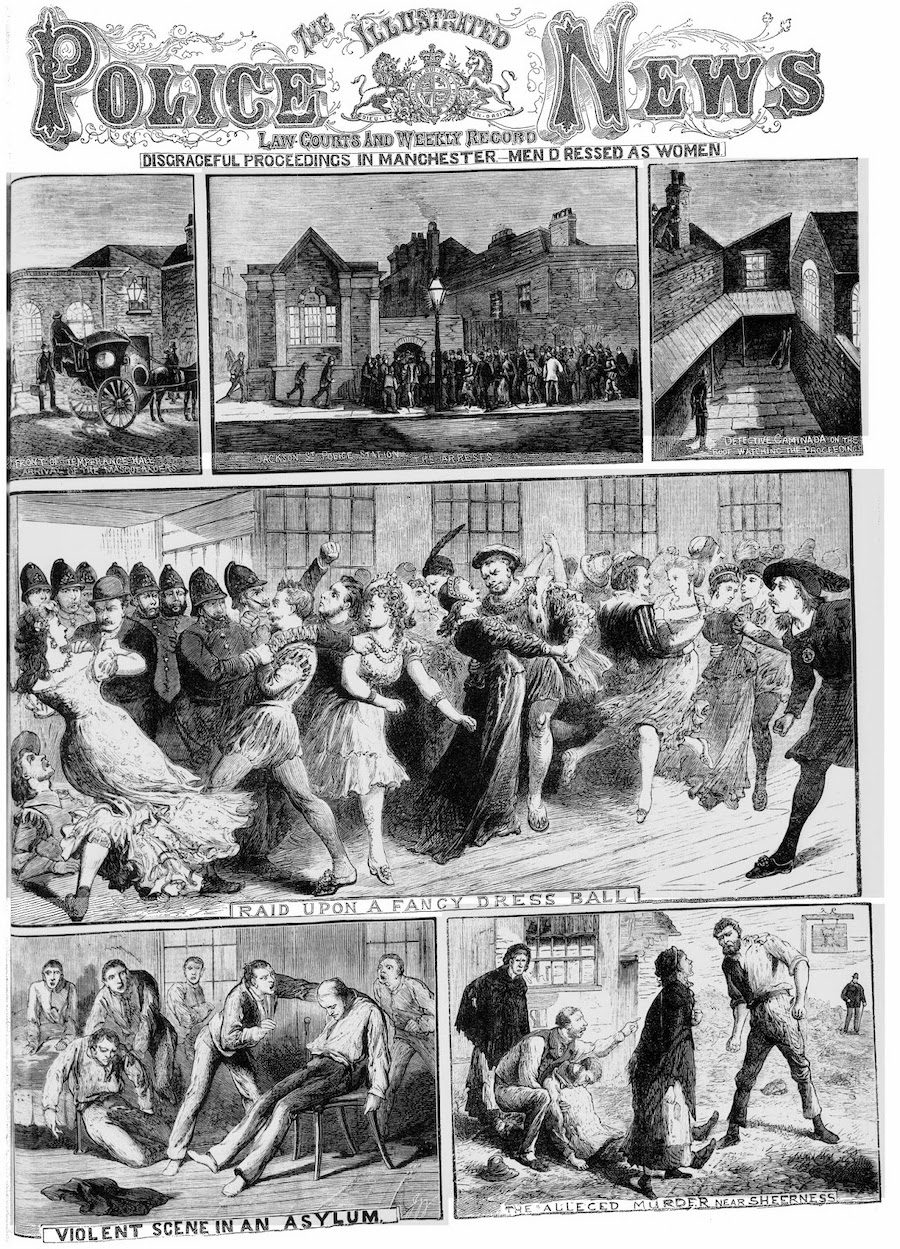

Still, that didn’t mean the community members like von Teschenberg weren’t persecuted for simply being themselves in Berlin, other big cities where queer scenes thrived. “Almost always, several secret policemen are present that make sure that nothing disgraceful happens,” Hirschfeld noted about the balls. In fact, just across the pond in Manchester a few years earlier the police raided what sounds like an otherwise epic ball at Temperance Hall, where folks came in epic couple-drag (ex. King Henry VIII and one of his ill-fated queens, Romeo and Juliet) until a detective used the password, “sister”, to shut it down and take everyone to court.

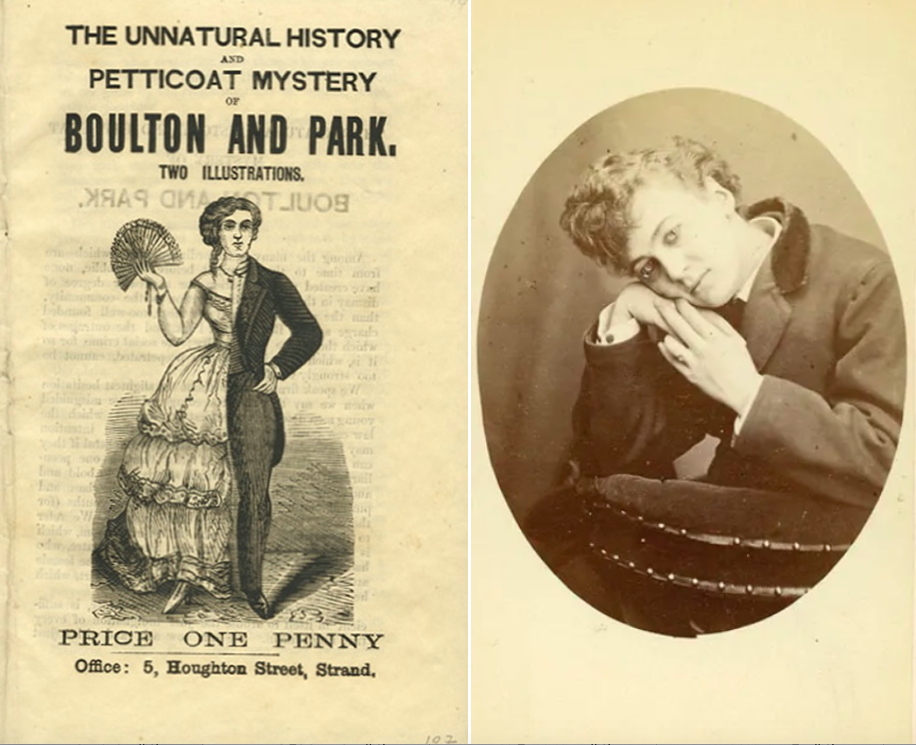

Meanwhile, in nearby London, there was the infamous case of Frederick Park and Thomas Boulton or “Fanny and Stella”. Now believed to be female transvestites, they began their careers on-stage as drag performers with their act, Stella Clinton (or Mrs Graham) and Fanny Winifred Park. Eyebrows began to rise, however, when they consistently wore women’s clothes to swish gatherings at the West End and other social events. In 1870, during an otherwise normal night at the theatre, they were both arrested by the police and thrown into court for “supposed homosexual acts”. The only thing more painful than their kamikaze trial? The public crowds it drew.

Now Fanny and Stella’s spotlight was clearly cut a little too short, so let’s just take a moment to drink in some of their most iconic looks, from Stella’s signature countryside shepherdess get-up, to their ensembles as croquet playing cuties…

Still, the queer community persisted, championing for the right to wear whatever they pleased, and love whoever they loved. “There is nothing wrong [in who we are],” declared a British queen called “Lady Austin” in the 1930s, “You call us nancies and bum boys but before long our cult will be allowed in the country.” In fact, up until the war, ball culture thrived across Europe and America alike. Queens in Paris participated in the “Carnaval interlope“, a drag competition with impressive hosts like Josephine Baker. In other words, kind of the original version of Drag Race.

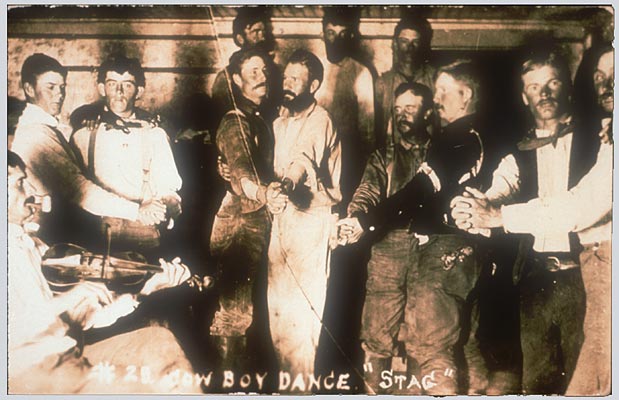

In America, ball culture had a slightly different story. In the wild, wild west where women were far and few between, pioneer towns would throw “Stag Parties” where men let loose with one another on the dance floor and sometimes came dressed as women. Yee-haw.

Cross-dressing in the States was also common in 19th century débutante balls, or on college campuses. One thing led to another, and what began as a bit of costumed fun snowballed into an entire queer scene. Almost always, balls were topped off with a “Parade of the Faeries”, in which the queens did one final prance for the judges in their looks, and were rewarded a cash prize judged by a panel of literary stars and show business personalities. Literally a 100-yr-old version of Drag Race.

But of all the places to take drag into the future, NYC was really the place to be. Many of the balls were able to gain police permits in Manhattan – one of the true epicentres of big ball culture – where they were thrown at illustrious locations like Madison Square Garden, Webster Hall, and the Astor Hotel. Above all, the important thing to realise about American ball culture is its vital connection to black communities.

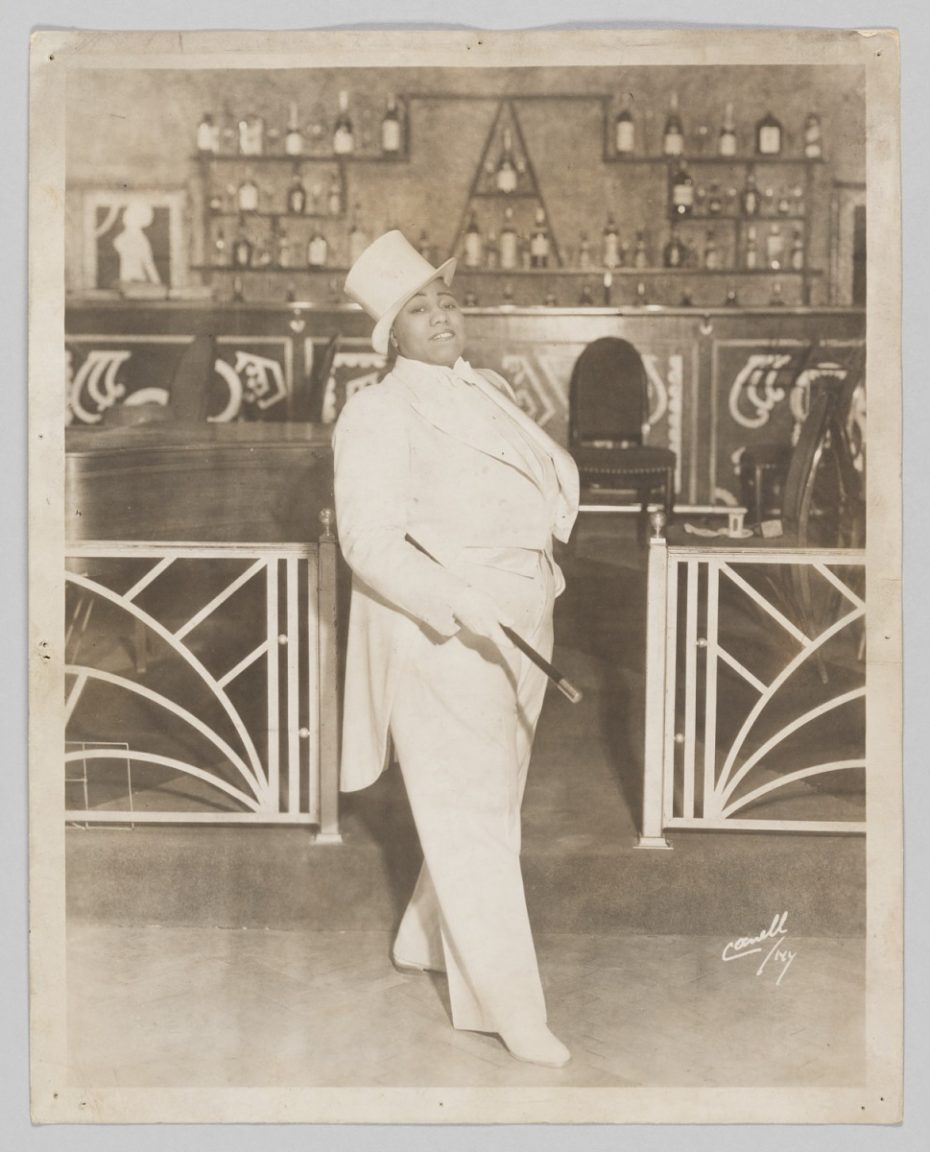

Sure, there were balls in Greenwich Village, but it was Harlem that hosted the biggest biennale ball: the Masquerade and Civic Ball. Now this wasn’t your average, underground drag ball – it endured as one of the it-parties of the city into the 1920s. And you didn’t have to be rich or poor, black or white to attend – you just had to have lipstick. Sadly, it was prohibition that temporarily stifled New York City’s drag culture. But isn’t that always the case with marginalised creatives during oppressive social periods? These queens were tough broads. In the face of bigotry, they clapped back with even bigger, better drag. That RuPaul has successfully brought the pageantry of drag to millions of small screens isn’t just amazing – it’s long overdue. So let’s raise a glass to the drag stars past and present, from Fanny and Stella, to Harlem’s Gladys (above); from Mama RuPaul to the queens whose names history has forgotten.