How many times have you seen you today? The fact is, the modern mirror as we know it today didn’t arrive until 1835, which means throughout most of history, people have been getting creative to know what they look like – if that’s what they were really looking for at all. The mirror’s relationship with reflection made it an object of both spirituality and wealth; a tool for practical science, and vanity alike. The story of how we got to the modern mirror reflects more than just technological innovation: it’s the key ingredient to humanity’s ever-blossoming love affair with itself, equal parts enlightening and delusional.

At its most primitive, the first ‘mirror’ was nothing more than a puddle in nature. The most infamous story is arguably that of the Greek god Narcissus, whose obsession with his watery reflection led to his own doom. Personally, we think he gets a bad wrap and wouldn’t blame a guy for being so fascinated with reflective surfaces in a world where mirrors didn’t yet exist. The earliest manmade mirrors were polished disks of metal or stone such as shards of volcanic glass in Turkey circa 6200 BCE, sheets of bronze for the Ancient Egyptians and pieces of iron ore and copper for the Mayans.

Mosaic mirrors of pyrite (aka “fool’s gold”), were crafted across large parts of Mesoamerica in the Classic period, but because Pyrite degrades with time and loses its reflective qualities, they were often mistaken for paint palettes or pot lids when excavated centuries later. Still, ancient mirrors no doubt would have provided pretty poor image and colour quality, requiring frequent and rigorous polishing to achieve any kind of decent reflection.

This well-preserved ancient bronze mirror, pictured above, from China’s Han Dynasty (currently for sale here) gives us a fairly good idea of what our early ancestors might have been working with – but only the elite would have afforded such expensive objects made by highly skilled artisans of the royal courts.

Some historians think that the rise of proper metallurgy saw the mirror become a tool for warfare, with one legend recalling the Greek inventor Archimedes using mirrors to set fire to a fleet of enemy ships. In fact, mirrors were commonly used for utilitarian purposes in the ancient world and Inca men wore bracelets with small concave mirrors attached for starting fires called chipanas.

In the year 2019, it’s easy to forget just how magical a mirror was, but ask any modern day Wiccan and they’ll tell you it’s right up there with wands and crystal balls when it comes to connecting with the dead. High ranking Chinese, Aztec, Indians and Egyptians all buried their kin with some form of a metallic or stone mirror, whose glow and round shape often evoked the sun and cosmos. Mirrors of Peru’s ancient Huari were discovered buried on the chests of royals, while those buried in the Temple of the Feathered Serpent at Teotihuacan had them placed on the small of their back.

Far from being a personal cosmetic accessory, mirrors were ceremonial, divinatory aids and often used as part of elite costume. If they looked into the mirror, it wasn’t to admire themselves, but rather to communicate with another dimension of deities and supernatural beings. In Ancient Egypt, mirrors would stay wrapped up in a cloth unless in use for protection, as if making sure you shut the door to the spirit world. They believed in the existence of an alternative self – known as the “Ka” – who could be reached with the help of scrying through a mirror.

To “scry” is basically to divinate, and a tradition that endured from the ancient cultures of the Egyptians, Mayans, etc., into the hobbies of the Victorians (Lord knows Victorians love their death). You see, you can scry into a crystal ball as much as you can a mirror, and it was common for mediums to carry a black-painted scrying mirror in their séance tool belt. You could even get started with your own scrying mirror kit here from Etsy.

Of course, mirrors were also just the best tool for making sure you didn’t have a hair out of place. Despite their strong spiritual beliefs, Ancient Egyptians were also one of the first cultures to clearly straddle the line between using mirrors for cosmology, and scrying. The very wealthy would use them to apply that famous Cleopatra cat eyeliner, paint their lips and generally indulge in a little vanity. During the Medieval period, mirrors fell out of favour due its history with the supernatural world. In the Middle Ages in England, “a woman who wore make-up was seen as an incarnation of Satan,” and it was commonly believed that the devil could watch us from the other side of the glass. Even when mirrors were back in our good books, they were among the most expensive items to possess, reserved only for the extremely wealthy up until the 18th and 19th century.

The secrets to mirror-making innovations were guarded in guilds, most notably in Venice, where Venetian glassmakers perfected a superior method of coating glass with a tin-mercury amalgam, producing an amorphous coating with better reflectivity. They also became experts at inserting gold leaf into the glass of a mirror’s back to add an eternal, warm glow your reflection, like the very first Instagram filter in a way.

Industrial espionage in mirror-making was thus … off the chain. The French and English hired spies to steal tricks from the Venetians and bring them into factories like the Saint-Gobain Factory in Picardie, France – one of the last that is still going strong today.

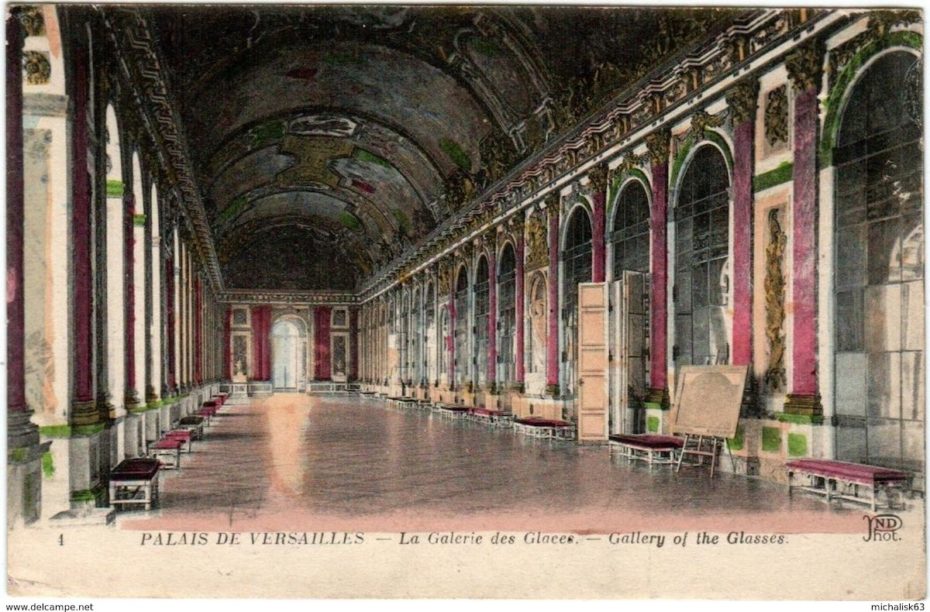

Their work rivalled the Venetians and hit an all-time high when the Palace of Versailles commissioned some mirrors for their hallway. Yes, that hallway:

The mirrors of this period would have often been made in two or three sections, and it’s important not to assume an antique mirror has less value if it was produced in sections, as this was the only means of production at one point in time.

Over time the reflective silver mercury found on the back of an antique mirror glass can corrode, a reaction which occurs due to oxidization, and appears as cloudy spots on the mirrors glass. These spots and a yellow grey colour of the mirror glass reflect its age and authenticity.

It was in 17th and 18th century France that mirrors really began to find their place in interior design. Prior to the high Renaissance, it was unusual to have even small mirrors set into the decor. As mirror glass became easier to produce in larger squares, it would occasionally be incorporated into paneling (or boiserie), which saw the rise of the French Trumeau mirror, set into tall wooden frames with a large section of painted or carved sculptural decoration at the top. They would often include candle holders at the bottom of the wooden framing to reflect light in dimly lit rooms.

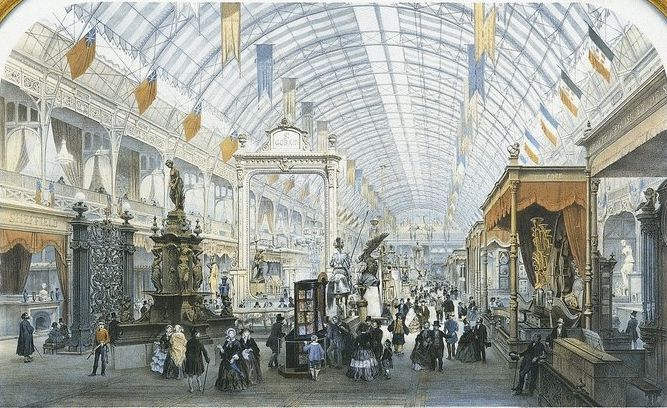

Once the Industrial Revolution was under way, new processes for mirror-making hit a stride that could democratise the mirror. In 1835, German chemist Justus von Liebig had a breakthrough when he replaced their reflective backing, usually a poisonous amalgam of tin and mercury to be handled with the utmost care, with cheap materials like aluminium. That steely, cool reflection is the mirror as we know it today (as opposed the glowing mirrors of Venice and Versailles). As production costs plummeted, Liebig transformed mirrors into less of a mystery and more of a commodity. Still, in 1899 there was a giant mirror on display at the Paris World’s Fair amongst all the other “structures of the future” as true marvel:

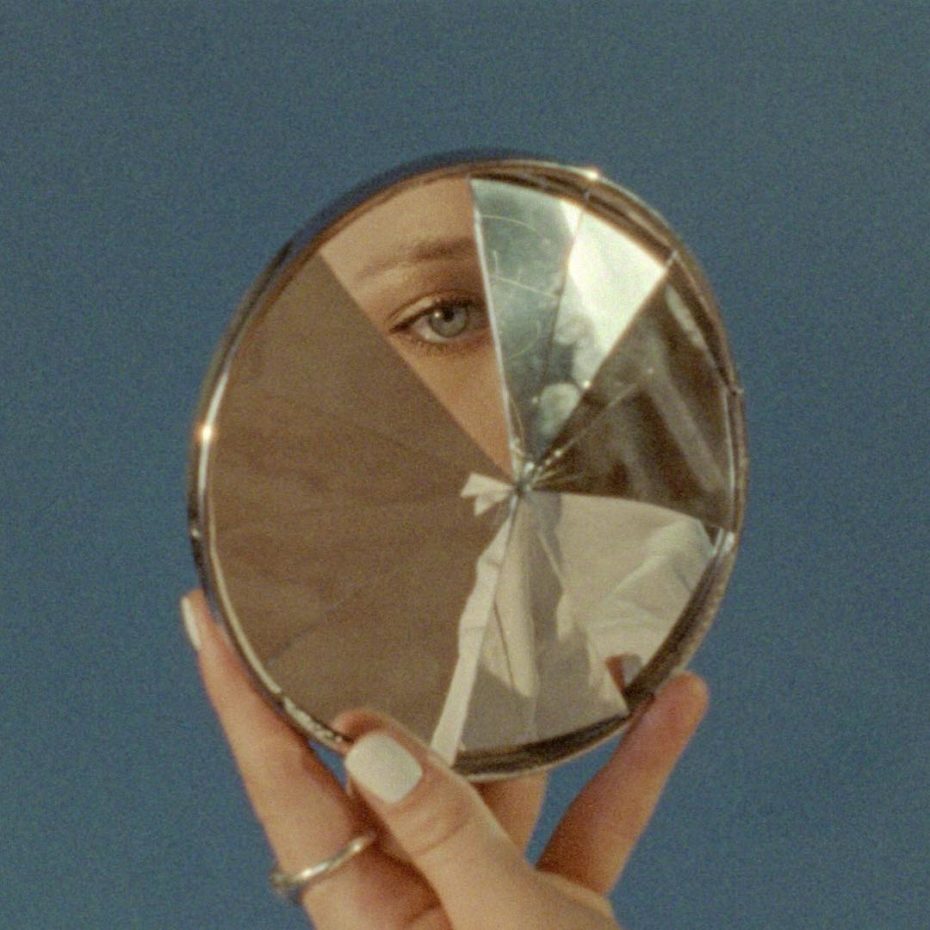

Even today, the quest to perfect the mirror as an accurate reflection of how others perceive us continues. As Dartmouth physicist Marcelo Gleiser explains in his essay, The Asymmetry of Life, “Look into a mirror and you’ll simultaneously see the familiar and the alien: an image of you, but with left and right reversed”. Even Lewis Carroll clocked that fact as the basis for 1871’s Alice Through the Looking Glass, in which young Alice knows the inner workings of the mirror-portal to Wonderland are perverse. Think of it like this: when you flip an image on a computer, it just takes on a weird new air. Well, that’s a simplified, parallel comparison to a rather unsettling realisation: most of us have never seen what we really look like. Unless, of course, you’re the inventor John Walter. Since the 1990s, Walter has become a bit of a sensation with his “True Mirror”, built to show us what others see – and not ourselves – when we gaze upon his looking glass. In the 1980s, Walter says he “first independently discovered that a true image reflection was possible by putting two mirrors together at right angles,” says his site, “It wasn’t a new idea, actually patented in 1887, but no one ever saw it as more than a physical curiosity. A True Mirror is an optically perfect (or as close to possible perfect) non-reversing mirror.”

Walter’s True Mirror travels the world to reveal people as they really are. “You may laugh,” he writes about people’s reactions, “You may cry. You may or may not like what you see. Not everyone gets it”. On the one hand, it’s a little scary to realise so much potential for an existential crisis can fit into one, tiny compact floating around your bag. On the other, in an age where the degree to which we modify, and engage with, instantaneously edited versions of our “selfie” selves, Walter’s invention dares us to peer into the looking glass not to enter Wonderland, but shatter it.

One last fun fact to leave you with – did you know that mirrors made it to the moon? Apollo 11, 14 and 15 missions have left mirrors on the surface of the Moon to calculate the distance between the Earth and the Moon by aiming a laser at them. Scientists have confirmed that the Moon is spiralling away from Earth at a rate of 3.8 cm per year. Going back to our ancient ancestors beliefs, perhaps mirrors might reach us from another dimension one day after all.