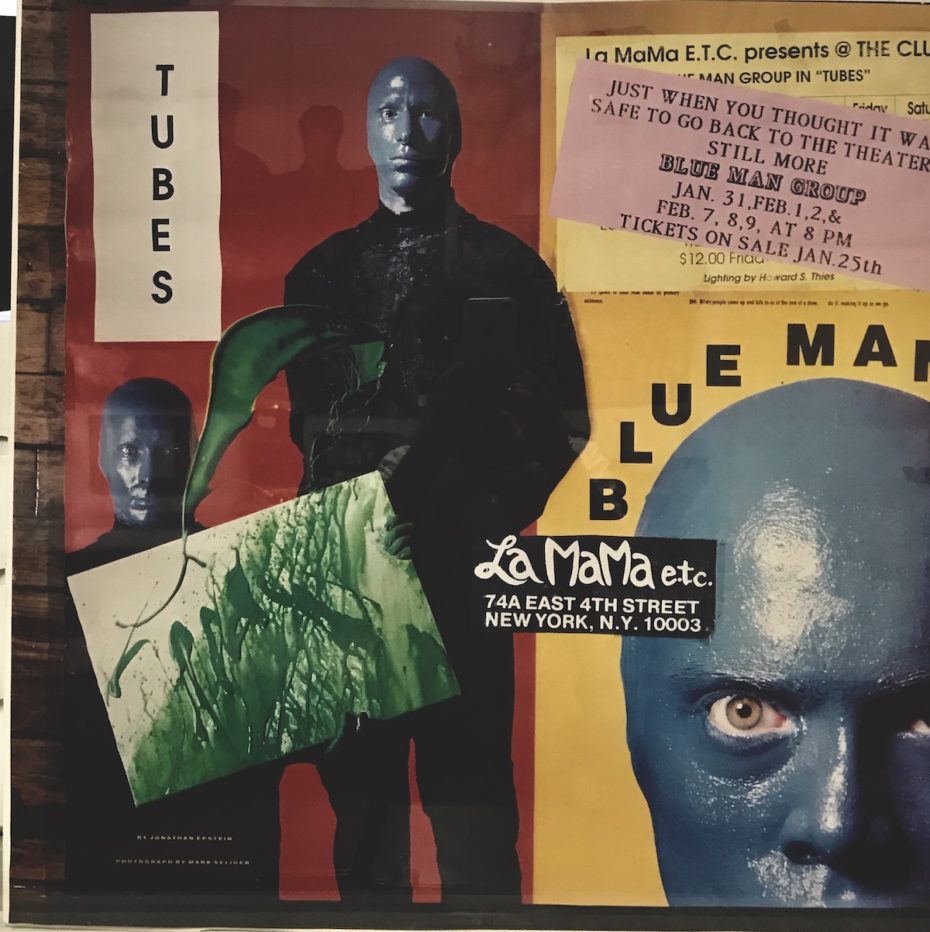

In 1961, New York City was sizzling. Musicians, comics, artists – anyone selling a song or a run-on sentence made their way to Manhattan’s East Village to make it big, or have a hell of a lot of fun trying. There, the streets were electric, and for the the theatre crowd they led to one place: La MaMa Experimental Theatre Club. While Broadway was singing “Hello! Dolly,” La MaMa was howling out of a cage. When most theatre companies were only casting white actors, its late founder, Ellen Stewart, was fostering diverse talents abroad and in the Big Apple. La MaMa was, and remains, the best black sheep of Off-Off Broadway, an incubator for the industry’s biggest icons, from the Blue Man Group to Sam Shepard; Bette Midler to David Sedaris. And if you ask nicely enough, you too can step behind-the-scenes of its whimsical archive….

We knock on the Theatre’s doors on a summer afternoon to meet Ozzie Rodriguez, the Wonderful Wizard of La MaMa who’s been there since its inception in the 1960s.

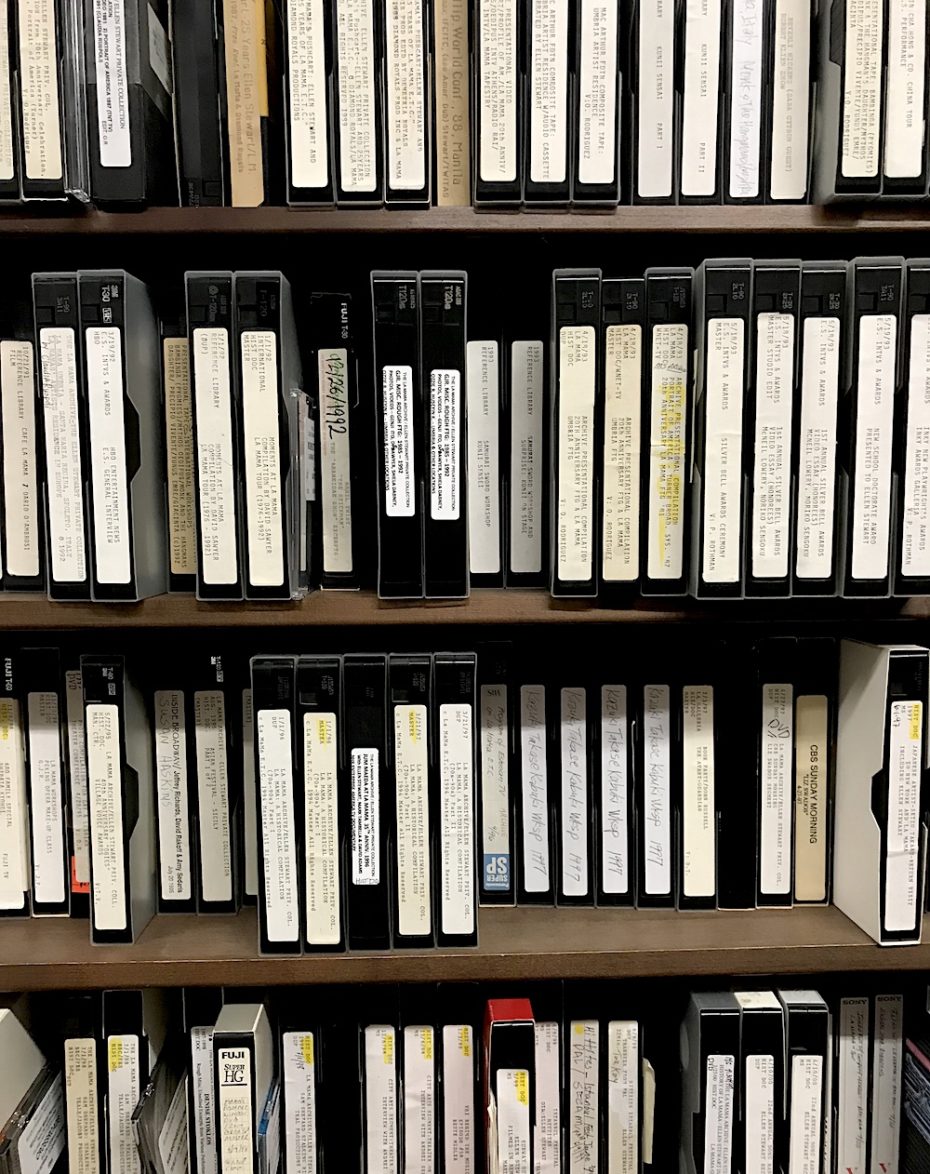

As a storyteller, his tales of bygone New York are fascinating. But as a guide, he’s indispensable, weaving you in and out of rooms wallpapered in puppets, masks, posters and more. They were all expertly saved by Ellen, who had a true talent for saving every last memento from their productions .

Ellen’s life is one that deserves a biopic of its own, and whose origin story at La MaMa set the tone for its spirit of hospitality and collaboration. She moved to New York City from Chicago in 1961 with aspirations to be a fashion designer, partially because New York had a reputation of being more open-minded to the prospect of working with designers who weren’t just white. She got a job at Saks Fifth Avenue, one of the department stores that was bringing the tradition of European glamour Stateside (ex. clients like the Rockefellers, the Morgans and the Du Ponts). Now at Saks, Ellen was just a porter in a green smock, but a fateful meeting with a fabric shop owner in Manhattan’s Lower East Side helped steer her course towards theatre.

One of Ellen’s favourite pastimes was to take the subway, and get off at random to explore the city. One day, she landed at Orchard Street in Manhattan, which was then a Jewish neighbourhood thriving with various mom-n-pop shops, fabric stores, and pushcarts. Ellen was taken with one fabric store pushcart in particular, but resigned herself to browsing as she knew she couldn’t afford any of the pieces. Suddenly, she’s invited in by the owner, a Romanian Jewish man named Abraham Diamond. Seeing her talent and enthusiasm, he gives her scraps of fabric, and a friendship forms – every Sunday becomes a pilgrimage to his home to exchange stories, scraps, and feed one another’s creativity.

Ellen’s designs were soon noticed by the customers at Saks, and she was given her own atelier on the side. Her sewing team was made up of WWII refugees who, knowing little English, started calling her “Mama”. From a porter, to a designer, to a designer with not one but two gowns present at the Coronation of Queen Elisabeth, Ellen was climbing the ladder. When she planned to open her own boutique, she decided it could double as a theatre to help her playwright foster brother and their friends. Diversity and open-mindedness had always been her ally, and the launch of the theatre kept that creative streak hot – new faces, plays, designers, etc. were flowing in.

La MaMa was first born in the little basement of a tenement building on East 9th Street. “We were her baby playwrights,” recalled Jean-Claude van Itallie, “and she sat on us like eggs that would hatch. She told us that what we were doing mattered, and we wouldn’t get confirmation on that anywhere else.” She gave them the go-ahead to be unapologetically authentic, to create a collaborative space for talents in the industry, and that regard she was a true trailblazer. She simply did things no one had done before.

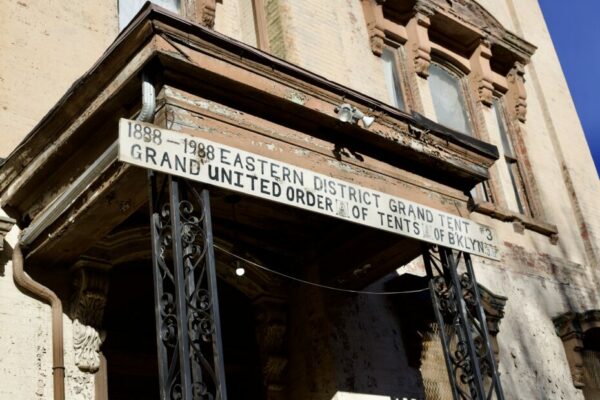

Strange noises and props escaped the theatre, puzzling neighbours. As a black woman with a steady stream of folks going to and from her basement, Ellen was also subject to racism and accused of running a brothel. Still, Ellen and her team found and created new spaces for theatre, and always landed on their feet.

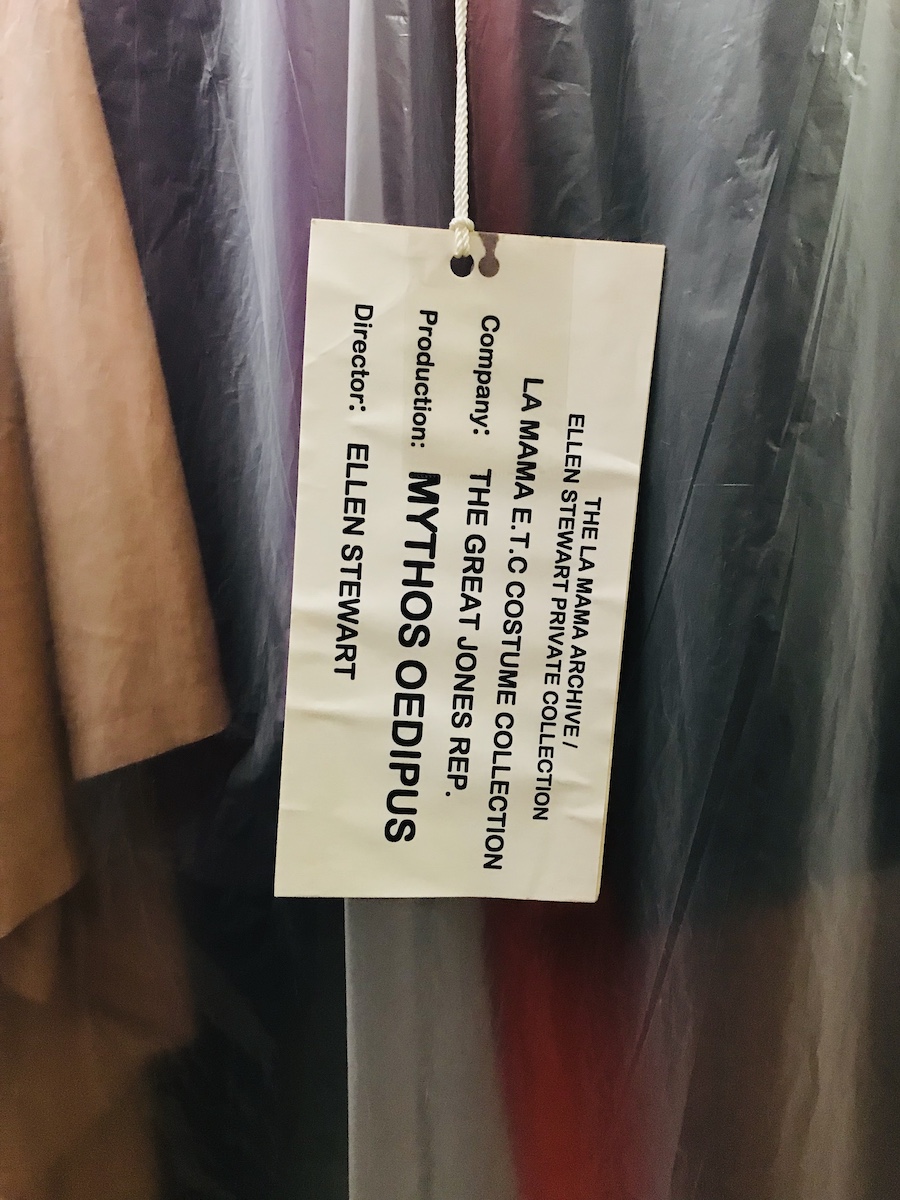

As we delve deeper into the space, Ozzie swings open a set of dark wooden doors for us to walk through – relics of a play, naturally – to yet another set of doors that leads to the exquisite costumes of the plays from what was truly a turning point in the experimental theatre community. That is how the archive by the Bowery unfolds: like a time capsule. Prior to Ellen, mainstream US theatre could feel, well, fairly saccharine. Those abroad knew My Fair Lady, Man of La Mancha, and Hello! Dolly. Ellen’s new artists showed the world that the US was cutting edge.

Ozzie explains that it was all commercial theatre prior, that all of the Broadway concoctions were written by the same small groups of people, with the same stars, again and again. There was little to no representation on the commercial stage for the kind of work La MaMa was doing.

La MaMa was doing not only Medea, but plays with names like “The Affectionate Cannibals” and “Buffalo Meat”. The actors were white, black, brown and everything in-between. Plays were multi-lingual. The most important thing, he explains, was that La MaM was a producing organisation with a truly open-door policy. The playwright, the director, the dancer, the kid on the street-corner who wanted to give prop making a try – they were all welcomed into the laboratory of La MaMa.

Their success was largely due to Ellen’s ability to not only provide a well of inspiration, but a calm in the storm of life into the latter half of the 20st century. Vietnam, Civil Rights, Feminism, Gay Liberation – all of these things, he says, were exploding at the same time with little or no commercial representation in the art world except at La Mama, and all in the same place: New York City, the Rome of the 20th century.

As the the ring leader of her ever-evolving theatre family, Ellen also had to be a powerful communicator. She went out of her way to tour her Resident companies make sure various foreign languages, cultures, instruments, and their traditions found a home with the experimental work of her artists. She was fiercely loyal to her vision, but dolloped every bit of direction with a “Baby…” beforehand. The archive, which was established in the early 1970s, was clever in that way: it became a life-sized encyclopaedia on how to run an Off-Off Broadway company with longevity.

The story of La MaMa is so intrinsically New York, and yet, so much bigger than a single city. Over the years, it’s presented more than 5,000 productions and fostered over 150,000 artists. It’s won dozens of Obies, a Tony, and even had one of its shows go from Off-Off Broadway to, well, on Broadway (a little something called Hair). Walking through the archives, essentially an open diary of sorts, isn’t just like walking into the toy chest of your dreams. It’s a privilege. This is Ellen’s open love letter to the city, the last gesture of her famous hospitality. Whether you’re a theatre junky or not, that’s one lesson we can all benefit from: if someone comes knocking on your door, let ’em in. You never know what kismet awaits.

La MaMa Archives is open to the public Monday-Friday from 1pm -4pm by appointment only. For more information please contact Archives Director, Ozzie Rodriguez at 212-260-2471 or email archives@lamama.org.