It was a flourishing trade in human flesh. A quest headed by art suppliers so ruthless in seeking out the perfect pigment, that it makes Dorian Grey’s creep-level look like amateur hour. It was the business of making “Mummy Brown,” a paint colour that quite literally required the ground up remains of mummies to achieve a warm, fleshy ochre that’s definitely been living in some of your favourite paintings. Mummy Brown was sold well into the 20th century, in fact, its story unhinges a whole ‘Pandora’s Box’ of longstanding abuse of ancient human remains as “material” for Westerners: as souvenirs, and museum pieces; as apothecary fodder, and black market trading.

Ever wondered why we call them “mummies” in the first place? Early archeologists found that Egyptian mummies produced a semi-solid form of petroleum called bitumen that’s used in asphalt, thought to contain healing medical properties (dabs of it were applied in ancient burial rituals to the mummies’ cloths). In Arabic, the word for the mineral is mūmiyā, hence the evolution into “mummy”, and the birth of the newest capitalist craze for those on the continent: breaking off a piece of that sweet, sticky bitumen and taking it to the bank…

One of our planet’s first historians, Pliny the Elder, praised bitumen’s medical ability to cure toothaches, bone fractures, pretty much everything under the sun: your One-a-Day vitamin, a thousand years ago. Westerners were enamoured by the idea that ancient mummies from the Middle East – be it people, cats, dogs, etc. – could provide an alternative source for the increasingly rare substance. There was an exoticized, spiritual healing element born out of the idea of eating ancient mummy bones – which, by the way, apparently smelled like garlic and ammonia.

You could literally head to Cairo, ask for the mummy man, and be led into a grave to pluck bones to your heart’s content. Germans, British, and French traders were all trekking to the Cairo to buy or barter for their own piece of the mummy market. Even Shakespeare’s son-in-law, a physician named John Hall who owned an apothecary, recorded his use of ground mummy bones to treat patients.

In the 16th century, a man named Abdel Latif wrote, “For half a dirhem I purchased three heads filled with the substance [of bitumen]”. When Napoleon invaded Egypt in the 18th century the hype really kicked in, and tourists started bringing home mummies as souvenirs.

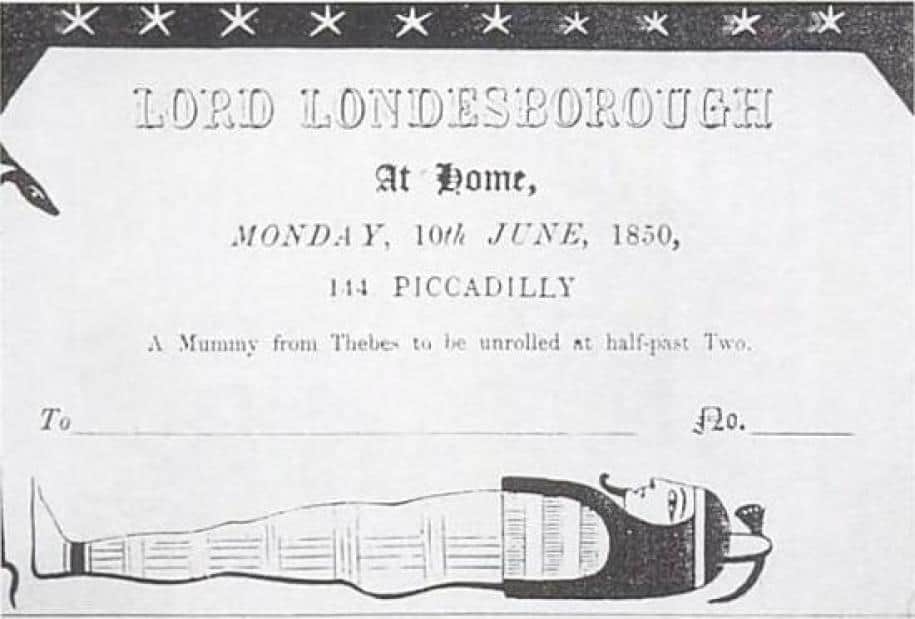

If one of your friends had just visited Thebes, you’d cross your fingers to snag an invite for their inevitable mummy “unwrapping” party:

“Two white eyes with great black pupils shone with fictitious life between brown eyelids,” wrote one Frenchman named Théophile Gaultier about his experience at an unwrapping party in 1857, “They were enamelled eyes, such as it was customary to insert in carefully prepared mummies. The clear, fixed glance, gazing out of the dead face, produced a terrifying effect; the body seemed to behold with disdainful surprise the living beings that moved around it. The mummy was placed upright to allow the operator to move freely around her and to roll up the endless band, turned to the yellow colour of écru linen by the palm wine and other preserving liquids….”

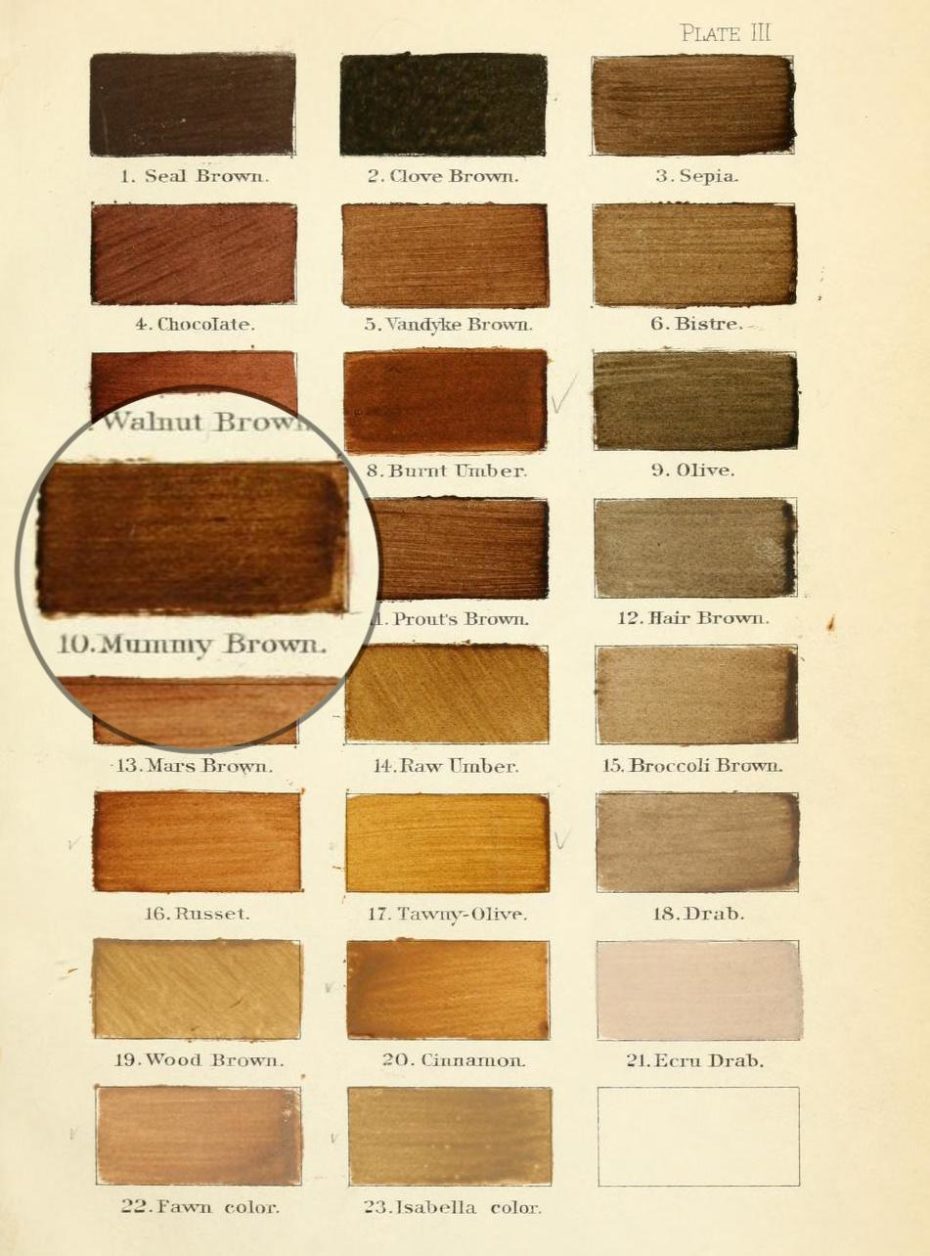

Mummy mania was in full effect. But as with every rising trend, the knock-offs began to roll in. Merchants sold the distorted remains of condemned criminals, and even birds and camels as ancient mummies. This relentless popularity of mummies is likely what led to their use in paint formulas: now, you not only had the novelty of consuming a mummy’s remains for supposed healing purposes, but you could paint with one. Pre-Raphaelite artists such as Martin Drolling and Sir Edward Burne-Jones were notable pioneers of painting with Mummy Brown. Needless to say, it makes Burne-Jones’ tragic works “The Last Sleep of Arthur” and “Clerk Saunders”, which portrays a woman being visited by her dead lover, run a shade darker that we ever could have imagined…

But were these painters entirely aware that Mummy Brown was actually made of mummies? The 19th century obsession with parlor-trick esoterism, Egyptology, and spiritualism meant that the name for such a colour was hardly shocking. For many artists, it may have been understood as a mere marketing ploy.

Simply put, if you were making it as a prolific and trendy artist, you were likely using Mummy Brown (or getting as close to the colour as you could get). On a side note: you can looks at many old paintings and gauge the importance of its content or client by the colour palette alone. The lush plum of “Tyrian Purple” was made of predatory snails, and great for dressing portraits of royalty. The blue of “Lapis Lazuli”, which was ground from the stone itself, was more valuable than gold. There was even “Dragon’s Blood”, a bubbling, bright red hue believed to be a mix of elephant and dragon blood. Casual.

Still, Mummy Brown crosses the line from the extravagant, to the disturbing. As viewers, knowledge of its pervasiveness can change how we interact with paintings we’ve known our whole lives. Consider Eugène Delacroix’s 1830 masterpiece, “Liberty Leading the People”. There’s that iconic flag waving in bleu, blanc and rouge, but it also contains a whole lot of brown shadowing – the kinds of things Mummy Brown was great for. Delacroix, too, was a noted fan of the pigment.

In the 18th century, Paris had a paint shop called “A la Momie” (To the Mummy), and the aforementioned Martin Drolling said he made his pigment from only the finest mummies: preserved French royals. There are rumours that the British fine arts supply company Winsor & Newton, which is still around today, specifically sought out mummy heads to make their shade “Caput Mortuum,” and another British company, Roberson and Co., advertised “Mummy Brown” in their catalogues until 1933. As one of the pre-imminent pigment suppliers, they had clients like Winston Churchill using their paints. When asked about the Mummy Brown pigment in 1964 by Time, the company’s director said, “We might have a few odd limbs lying around somewhere. But not enough to make any more paint. We sold our last complete mummy…”

So what put an end to the madness? For one, the paint’s lack of a viscosity meant it dried rather too quickly, and eventually cracked over its surface. There was also some ambivalence about what the shade was bringing to the table that other browns couldn’t, and the fact that ammonia and whatever else is found in human remains would soil the colour over time. The proverbial nail in the paint’s sarcophagus came when Burne-Jones was shooting the breeze with some artist pals, who politely told him that Mummy Brown was indeed made of humans. Disgusted, he ran to his studio and retrieved his brown paint tube and buried it in the ground.

The episode was described in detail by Burne-Jones’ nephew, an aspiring writer who the world knows very well today as Rudyard Kipling, author of The Jungle Book. “He [Burne-Jones] descended in broad daylight with a tube of ‘Mummy Brown’ in his hand,” he writes, “saying that he had discovered it was made of dead Pharaohs and we must bury it accordingly. So we all went out and helped – according to the rites of Mizraim and Memphis.”

The story of Mummy Brown opens up a discussion that’s very relevant to the topic of what, and how, our museums and cultural institutions decide to acquire their pieces. On the one hand, the excavation and study of mummies has helped illuminate our past, and in doing so, equipped us for the future. The remains of King Tut revealed he’d suffered not only from Malaria, but certain genetic diseases that we can now trace from the area of his burial. Still, what are the ethics of unearthing a grave? Ancient Egyptian Mummies never intended to end up at a museum in Brooklyn. It all begs the question: does our respect for the dead have an expiration date?