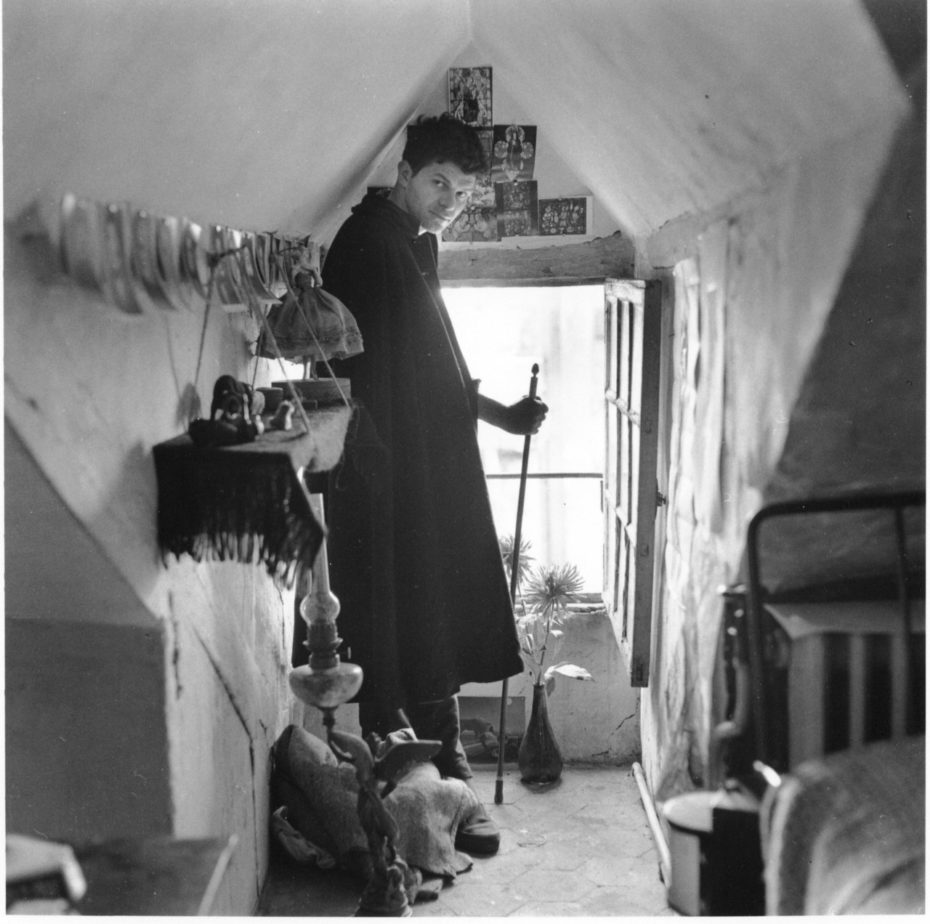

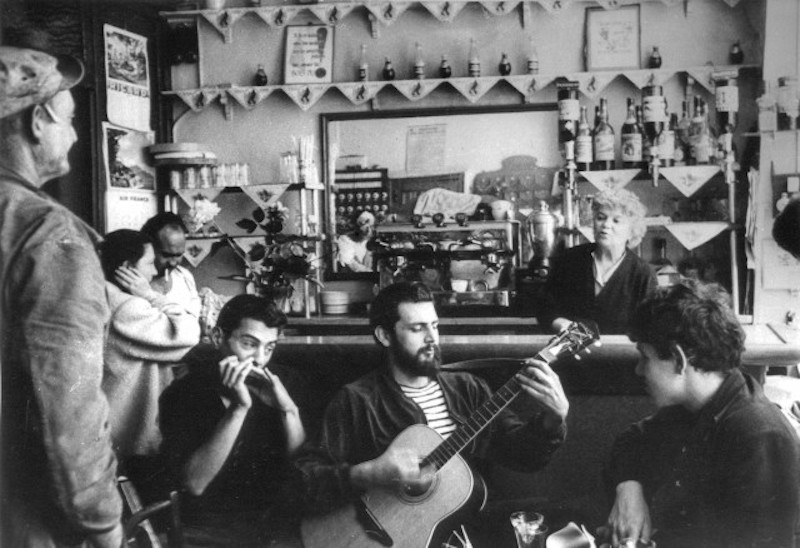

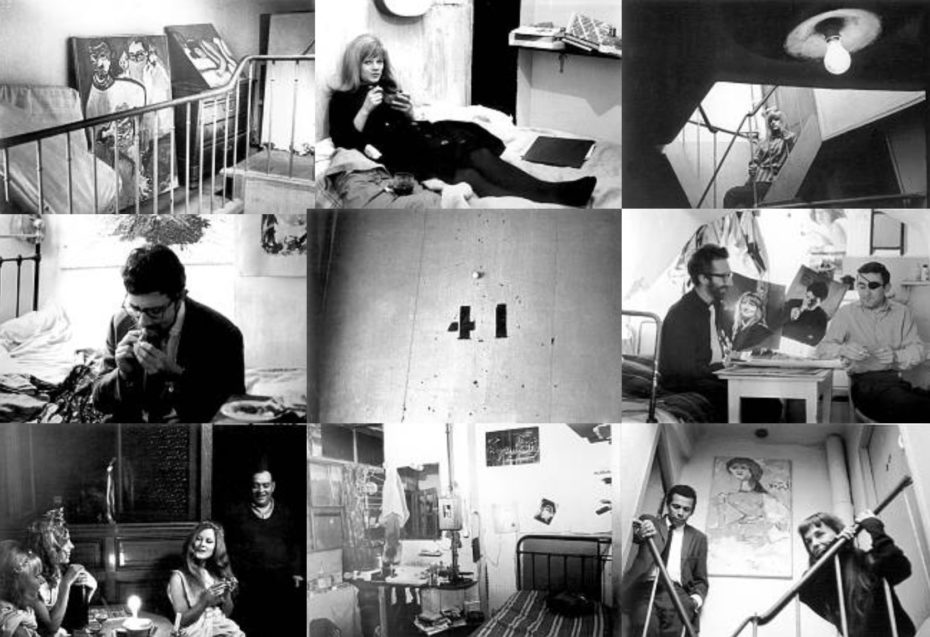

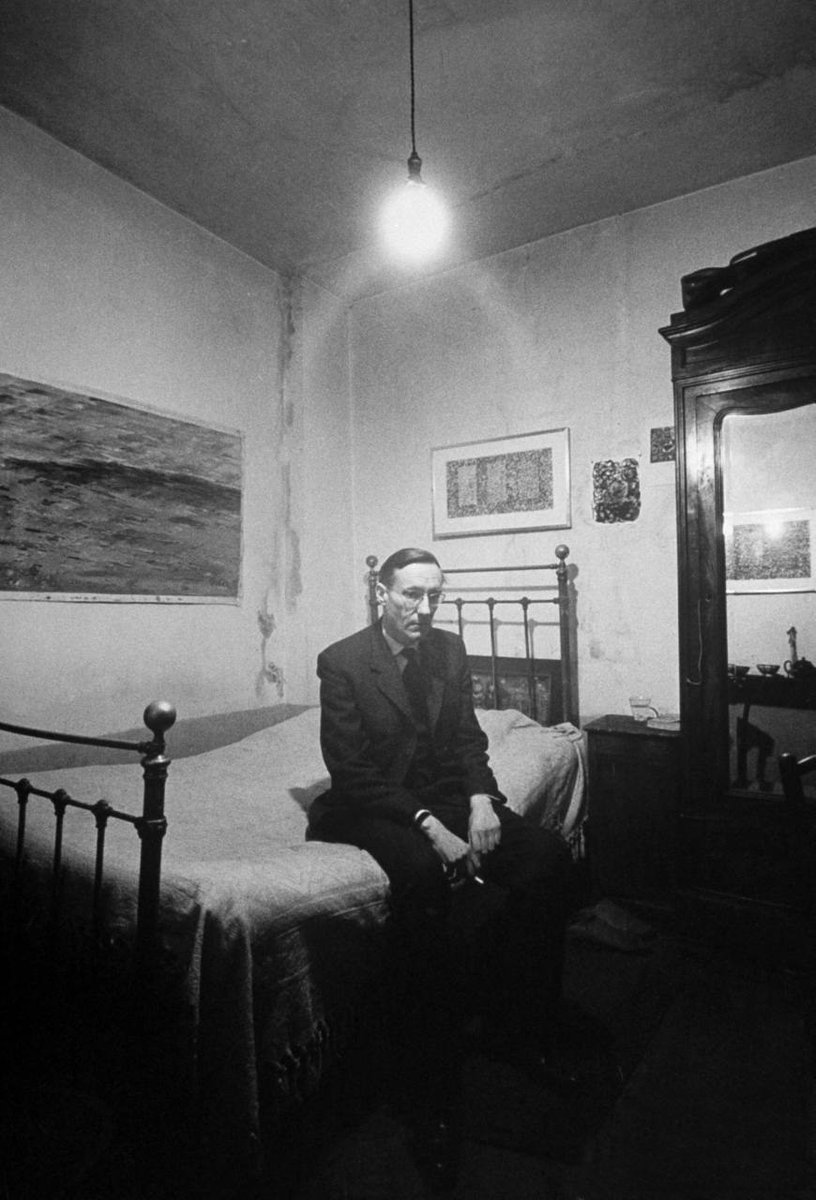

“I lay there on the floor, he makes love to Nanette all night, as she whimpers,” wrote Jack Kerouac, recalling the night he slept in Room 41 of a Parisian “fleabag” in the Latin Quarter that his friend and fellow poet had christened “The Beat Hotel”. Gregory Corso, the youngest of the inner circle of Beat Generation writers, would also introduce Allen Ginsberg , his lover Peter Orlovsky and William Burroughs to the Left Bank lodging house at 9 rue Gît-le-Coeur that barely met minimum health and safety standards. Bed linens were changed once a month, hot baths were only available on Thursdays, Fridays and Saturdays (from a single bathtub situated on the ground floor), and the rent cost $30 a month. When artists and writers were strapped for cash, Madame Rachou, the “patronne” would let them pay rent with paintings or manuscripts. Clientele were also permitted to to paint and decorate their rooms however they wanted. Writer William Burroughs, a troubled but primary character of the Beat Generation, who completed the final pages of his seminal novel Naked Lunch while drinking at the bar of the hotel, called Madame Rachou the “perfect landlady” with “inflexible authority”. The widowed Parisian became an unwitting mother figure to an international movement – one that influenced post-war American culture and politics – all from her rundown little boarding house in a back alley behind the Seine they called, The Beat Hotel.

“The main entrance of the hotel. The door, which was never locked, made a penetrating screech as it crashed shut, the sound of which could be heard on the top floor. Attempts to shut the door quietly would bring Madame Rachou out of her room to investigate”.

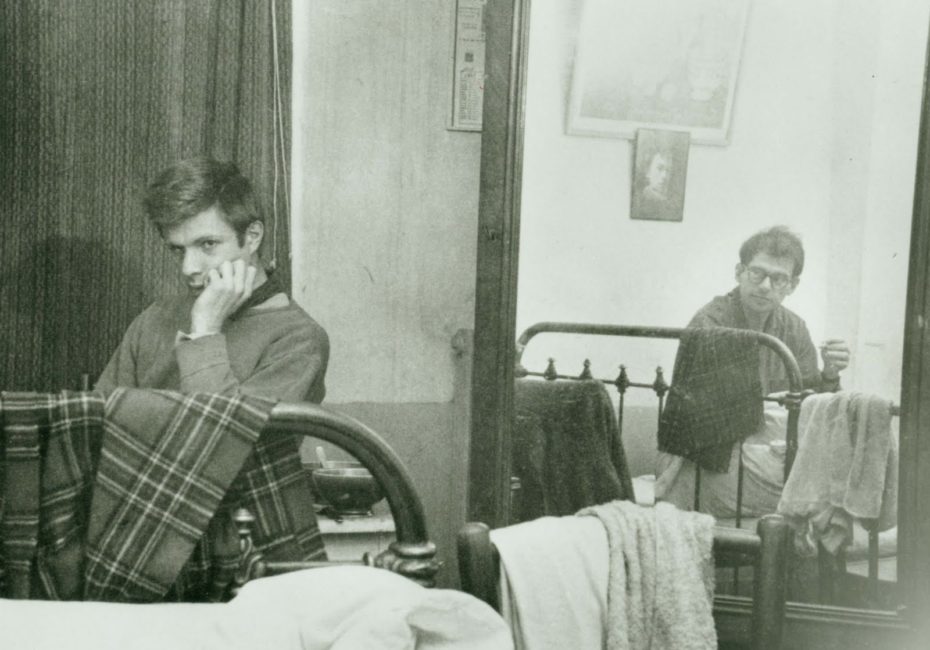

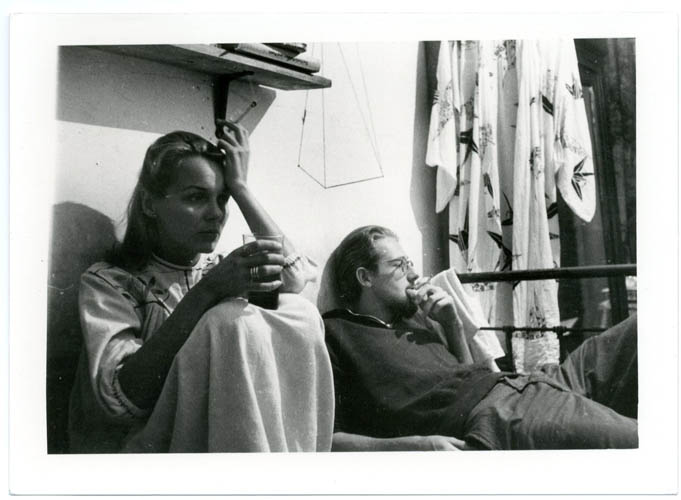

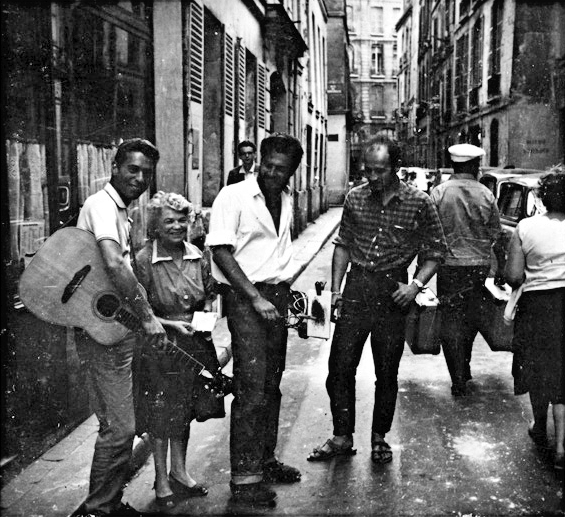

Photographer Harold Chapman lived at the Left Bank guesthouse for nearly 10 years, documenting the lives of its bohemian occupants.

“For a short time, I had an improvised dark room in an alcove no larger than a small wardrobe, blacked out with two blankets which I nailed up to the walls at night,” recalls Chapman of his most significant period. “I printed with an enlarger bought in a flea market, which stood on a couple of orange crates nailed together. I washed my prints in the sink and hung them up to dry on a clothes-line in the room. My films were scraps given to me by a cine cameraman.”

Many of the tenants used the hotel as their creative haven and studio. Painters stored some of their work on the top landing. Ginsberg wrote a part of his poem Kaddish at the Beat Hotel and Corso wrote the mushroom cloud-shaped poem Bomb.

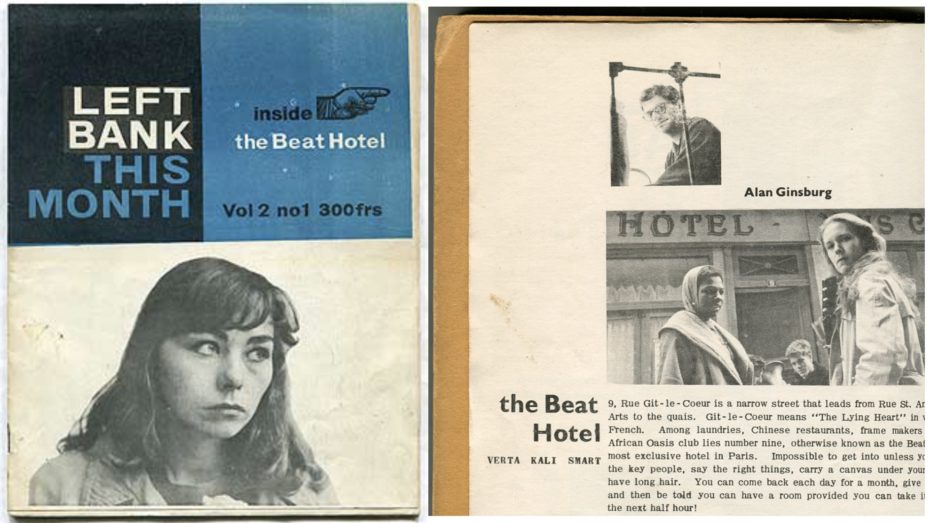

Before the band of Americans had come along, the 42-room hotel at 9 Rue Gît-le-Cœur didn’t have a proper name, until Gregory Corso gave it one. African American writer and tenant, Verta Kali Smart, wrote a cover story about “The Beat Hotel” for a long-lost ex-pat magazine called “Left Bank This Month”. The article was likely the first time the hotel’s nickname was published in print, making it official.

Verta wrote that the flophouse was near “impossible to get into unless you know the key people, say the right things, carry a canvas under your arm”.

Not everyone made it at The Beat Hotel of course. Harold Chapman remembers “Kaja”, a poet, writer and painter from New Orleans who came to Room 29 one evening and asked “Do you want to photograph the face of suffering?”

The hotel continued to gain fame as the Paris headquarters of the beat generation. Back home in America, the “extended family” of writers and artists were earning a reputation as the new bohemian hedonists, and Madame Rachou’s guesthouse was dubbed a “flea-bag shrine” by international journalists. Beat writer and resident Harold Norse defended her humble Left Bank establishment, declaring that “the flea-bag shrine will be documented by art historians”. He wasn’t wrong.

As a young woman, Madame Rachou had worked at an inn which operated similarly to her Beat hotel, welcoming emerging artists and writers to stay. Those emerging artists had included Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro. One might go as far as to suggest Madame Rachou was a bit of an unsung Sylvia Plath or Gertrude Stein for the Beat Generation.

When the Beat Hotel closed its doors in 1964, photographer Harold Chapman was the last guest to leave. “In January 1963, after 32 years, Mme Rachou ‘the blue-haired old mother of us all’, retired and moved to a flat nearby. The hotel had been sold, the handle of the cafe door had been removed, and a notice in the window read: Closed; for alteration. The Beat Hotel had ceased to exist.”

Today at 9 Rue Git-le-Coeur, there is a small 4-star hotel, “Relais vu Vieux Paris” with a plaque outside commemorating the famous guests of the original Beat Hotel.

Discover more of Harold Chapman’s work with the Howard Greenberg Gallery.