© Derry Moore

As a decorator, the late Madeleine Castaing embodied over-the-top luxury and la vie bohème. As a patron, no – diva – of the arts, Castaing’s eye for excellence helped sponsor some of the greatest artists of all time, from Soutine to Modigliani. During the height of World War II, she opened an extravagant boutique behind the Boulevard Saint Germain and held court there as the queen of interiors, well into her nineties. It became a legendary place and increasingly eccentric; like a Ms. Havisham’s Parisian lair or a portal into the pages of a book by Proust. Today, saying you’d like a room done in “le style Castaing” isn’t just decorative shorthand for elegance with a big kick of personality, it’s a challenge to a designer; a reminder that the best luxury shouldn’t just be bought, but brazenly assembled from the imagination.

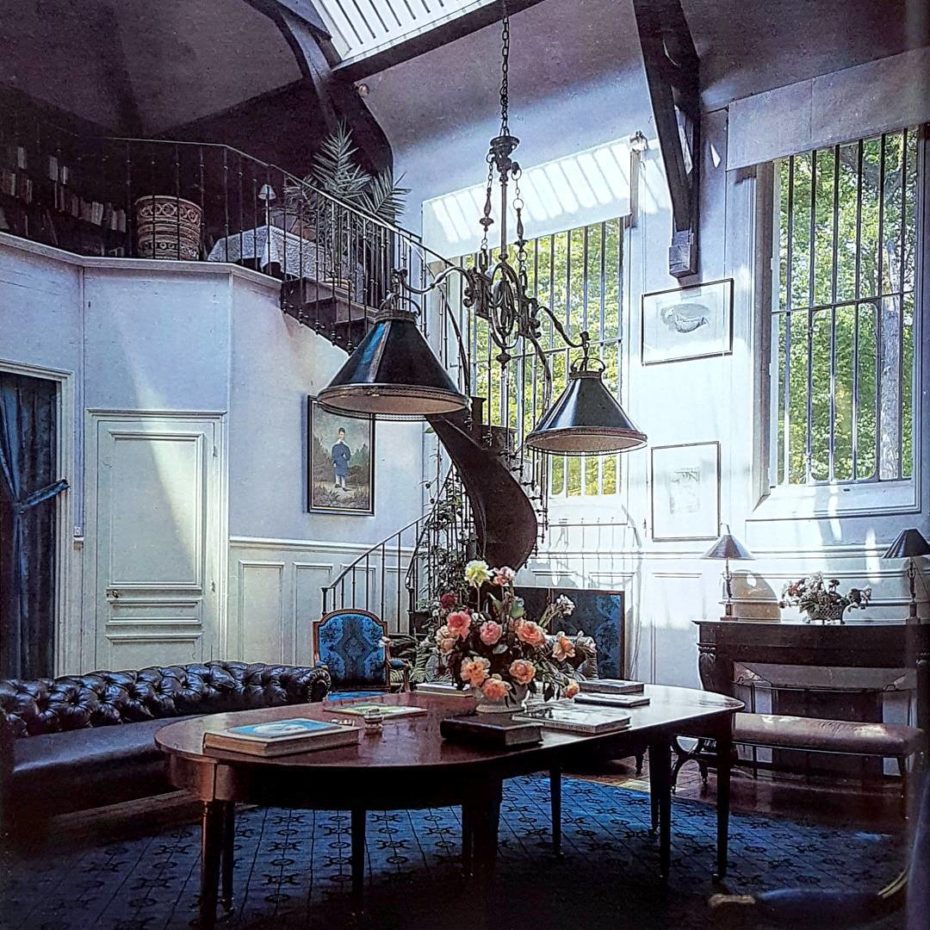

Castaing, née Marie Magistry in Chartres, was born into a comfortable social class, to an engineer father who designed the Chartres train station. At 16, she met affluent art critic and heir to a provençal wine fortune, Marcellin Castaing. He bought her a house in Chartres outside Paris that she had admired since she was a little girl, the enviable Maison de Lèves:

At first Madeleine was content as an affluent housewife, she briefly dabbled in silent films as an actress, but luckily, her husband’s fortune blessed her with the luxury of exploring what would become her true passion…

These days, socialite-turned-interior-decorators are a dime a dozen. What makes Castaing the queen of them all, after all these years, wasn’t just the sincere joy, or theatricality she brought to the endeavour – it was her seriously sharp eye for talent. She knew Soutine was what the 20th century needed. She knew Cocteau was a talent worth fostering. She invited them all into her home in Lèves, a sprawling country estate located an hour-and-a half southwest of Paris.

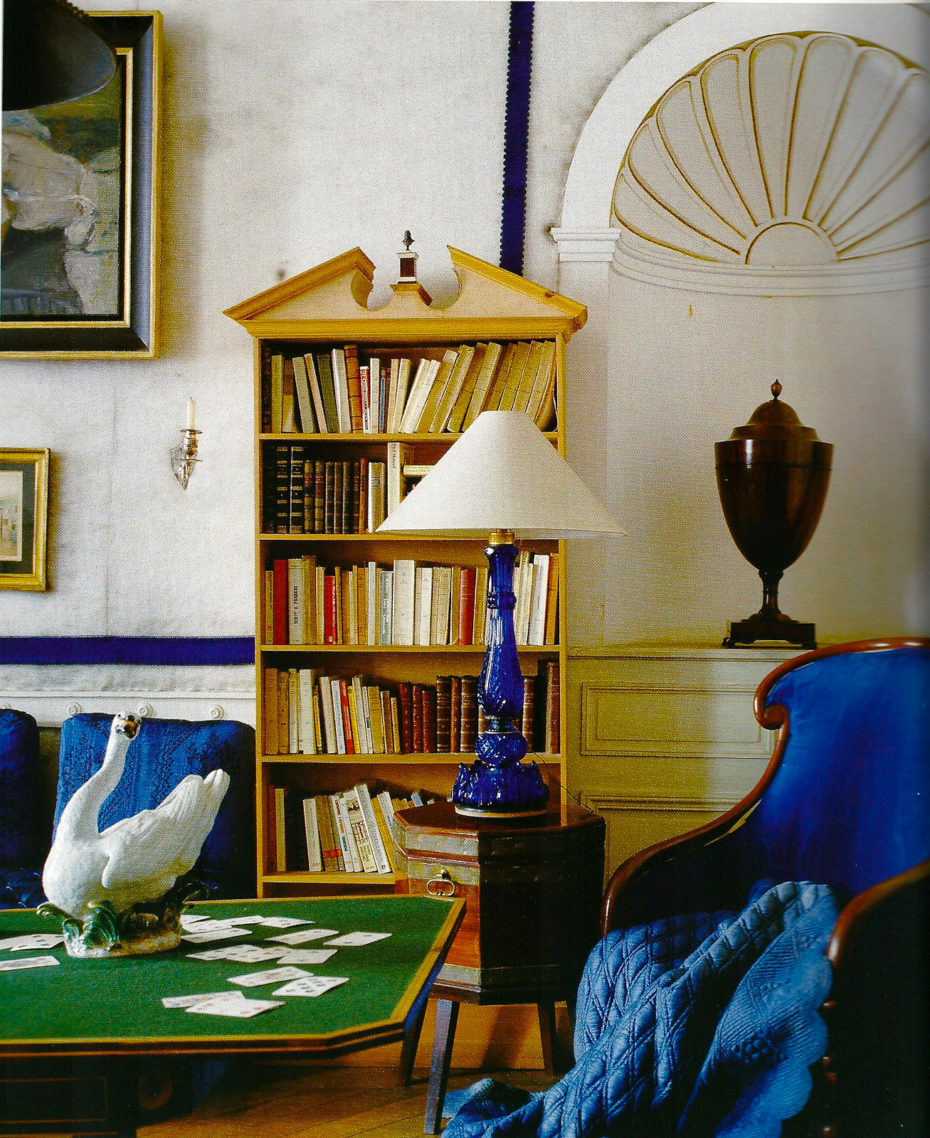

The Castaing colour palette consisted primarily of reds, greens, black, her signature Bleu Castaing – and wall-to-wall leopard carpets. On the drawing board, one would think she was mad. Napoleon III furnishings, English country antiques, and faux leopard Ottoman Empire carpet? In the same room?

On paper it was a cacophony. In reality, it was a symphony of culture and history. If she made it look effortless, it was because she was never trying to be fashionable. She was just trying to be herself. “When I decorate, I’m making portraits,” she once said, “which explains why some of them are so very awful”. We beg to differ.

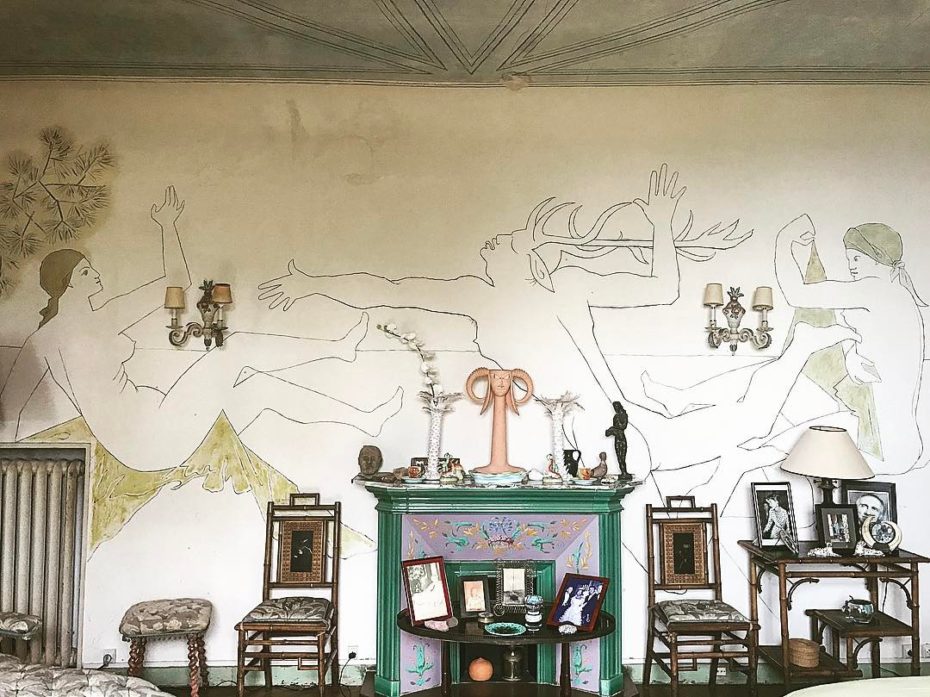

Bathroom of Jean Cocteau’s Villa Santo-Sospir, decorated by Madeleine

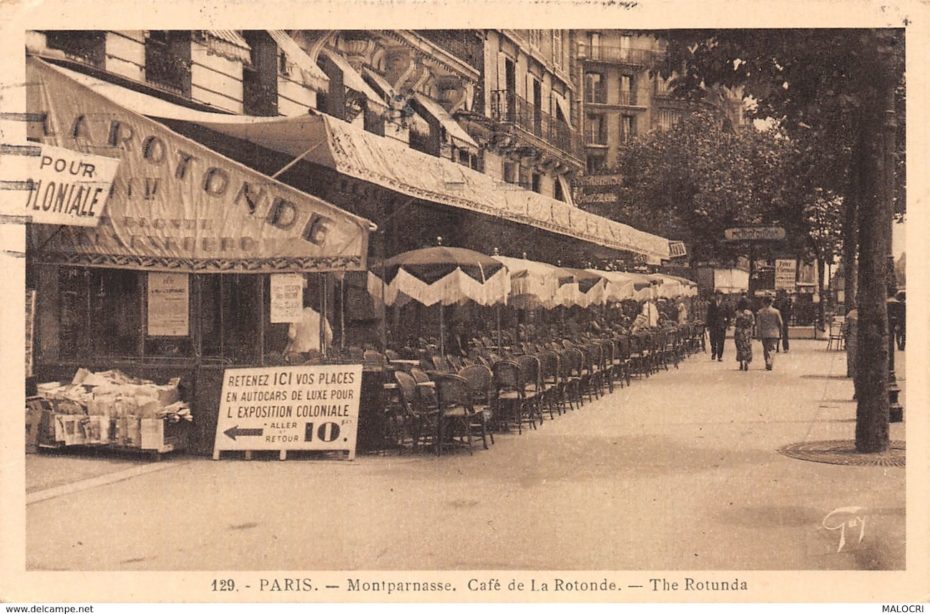

Madeleine perhaps had the most fun in Paris during the roaring 20s, scouting new talent on the boulevards of Montparnasse. It was the hot drag for bohemians, and the Café de la Rotonde – a favourite of the Catsaings – offered a front row seat:

There, she met Erik Satie, Andreé Derain, and Marc Chagall; Pablo Picasso, Henry Miller, and Jean Cocteau. She became a staunch supporter of Amedeo Modigliani. The writer Louis de Vilmorin was a dear friend, and the protagnost of her novel Julietta (of the same name) became an incarnation of Castaing, and her legendary love for Marcellin.

The relationship between Madeleine and Chaïm Soutine is one of the most intriguing artist-muse-patron dynamics in modern history. Their first encounter at la Rotonde was wonderfully awkward: so taken was Castaing with the painter, that she tried to buy one of his paintings on the spot, without even seeing it, for 100 francs. Soutine found it insane. Insane, but flattering. Both were young, beautiful and bright when they met, and some historians think they pined for a romantic relationship in secret. They were certainly inseparable, with Soutine even living with Castaing and her husband. At night, the troubled painter allegedly wandered the halls with a carving knife, slashing his own works. But in one video interview, Castaing recalls how the three of them would sit by the fireplace, talking into the hours of the morning about art.

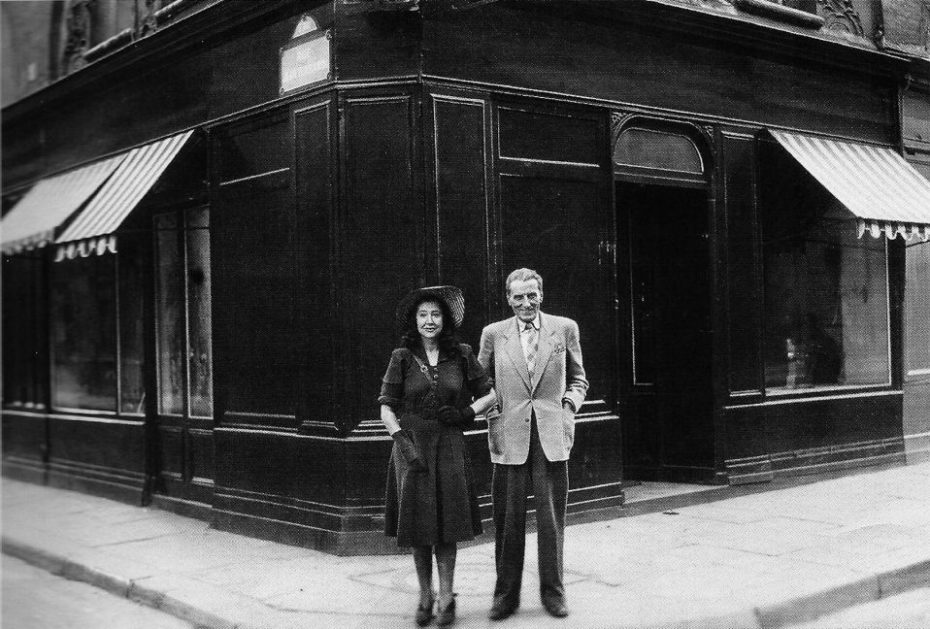

Having made a name for herself as a decorator by the 1940s, Castaing decided to open her own Left Bank boutique. A natural evolution of things, if you don’t count the fact that WWII had put a violent halt to so many other creatives in Paris. After the Nazis confiscated her beloved home in Chartres, she defiantly set up shop on the corner of rue Jacob and rue Bonaparte, and to stand out from the crowd, painted the exterior a dramatic shade of black.

Inside, it looked as if she’d sprung open her trunk of treasures collected from flea markets and faraway places. “Paris was sad, and empty,” she said about her decision to open a store during such tumultuous times, “The interiors were sad. You had less of a right to express yourself. I had to do it.”

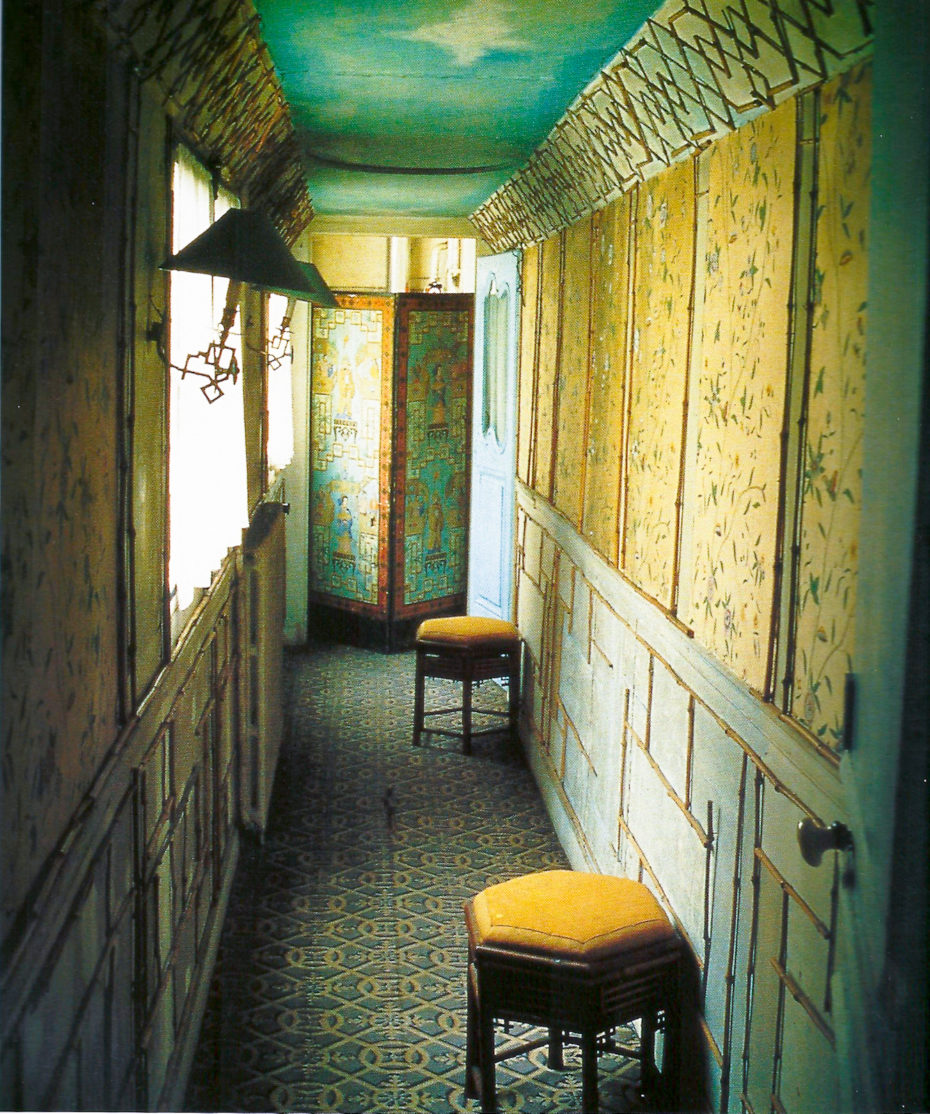

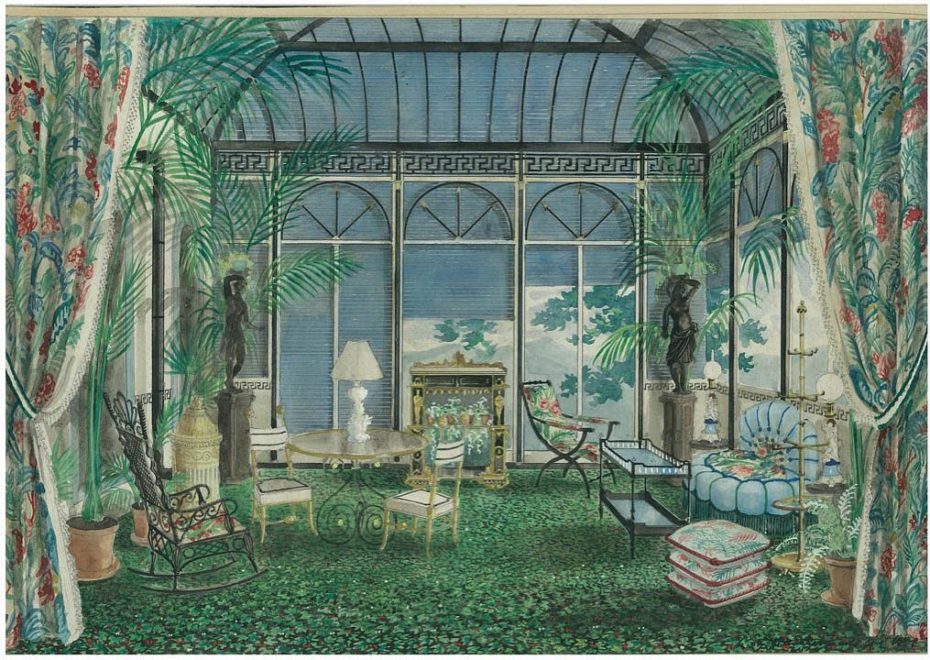

One of her most notable clients was none other than the multi-talented artist Jean Cocteau, who enlisted her to decorate his home, La Villa Santo-Sospir, at Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat:

A blank canvas was never an option for Castaing, who had to find a way to complement – but not overpower – the artist’s self-proclaimed “tattoos” that adorned the walls.

Scenes from mythology, his own unconscious, and homages to the sea were all prevalent themes. “When I was working at Santo-Sospir,” he once said, “I became myself a wall and these walls spoke for me.” Caistaing’s decor made for the perfect collaboration:

She insisted on living for 24 hours with a client, to understand what they’d need from her. “I want to put life into interiors,” she explained, “that’s what’s the most important. I have to do a long psychological study [of the client].” Together, they’d go to cafés, museums, walks about Paris. They’d tell her their life story, and she’d seamlessly translate it into furniture.

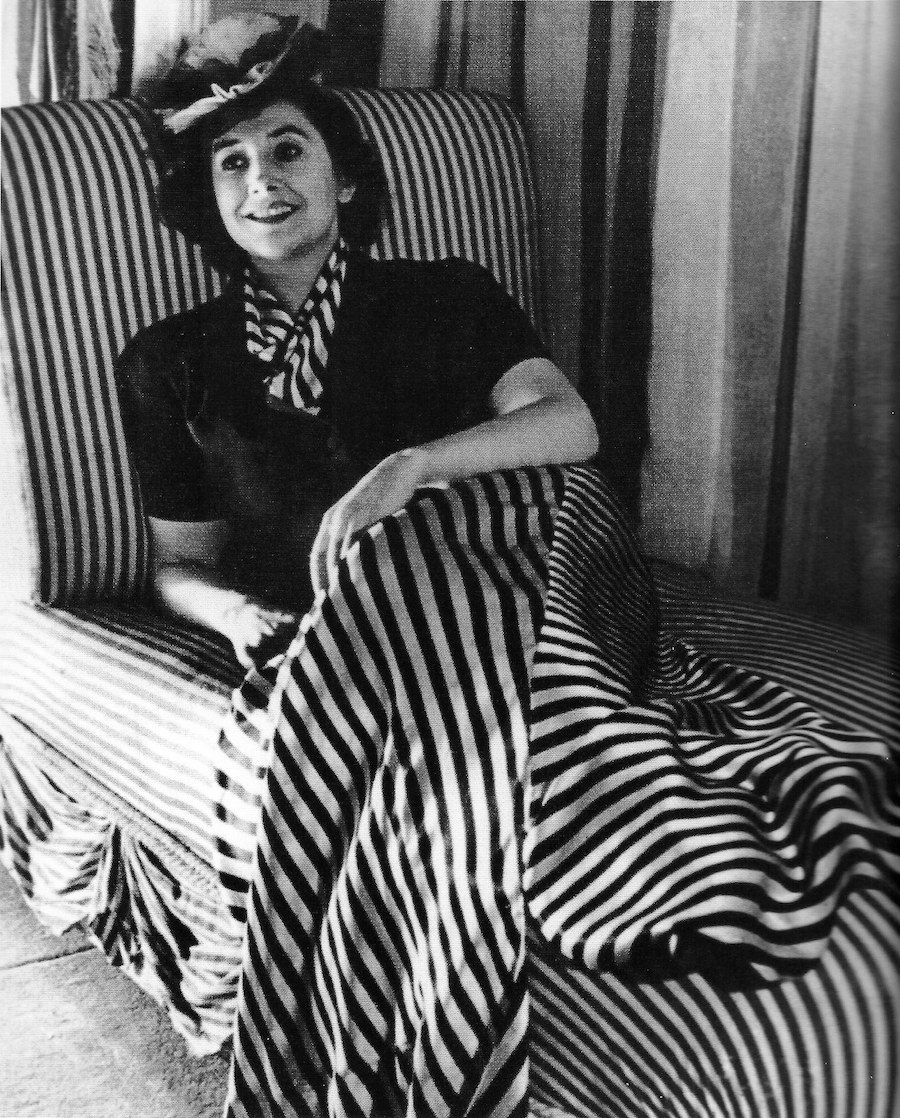

Her fashion and beauty choices adopted the same principals of her decorative technique, becoming all the more whimsical. She’d wear Raggedy Anne Doll-level eye makeup, and Clara Bow lips. She started rocking a wig over her own hair, and fastened it down with a visible chin strap.

As she grew more eccentric in her old age, her black boutique on Rue Jacob was often mistaken for a funeral home, which made it all the stranger when Castaing beckoned in confused passer-byes with her signature enthusiasm, chatting with them for hours on end.

Behind the facade, the furniture inside was falling apart, the winter garden was overgrown and Madeleine became somewhat notorious for refusing to sell to important clients or decorators she disliked.

Twelve years after her death, the Castaing empire at Rue Jacob finally went out of business and Sotheby’s held a once-in-a-lifetime auction selling the contents of the shop, her apartment above the shop, and her neglected home in Chartres.

Madeleine’s former stronghold on Rue Jacob was sold and replaced by the flagship store for French bakery Ladurée. And just like that, her eccentric world on the Left Bank disappeared. Two years after her death, a movie starring Jeanne Moreau, The Proprietor, was filmed in the apartment about her shop where she lived from 1946 until 1992. Today it’s the home of director Ismail Merchant.

It’s a beautiful thing when a person’s home invites you to step into the collage of their life, as it was in reality and their personal fantasies. Anaïs Nin once said, “luxury is not a necessity to me, but beautiful and good things are.” Castaing embodied that philosophy, and was just shy of 100-years-old when she died in 1992, leaving a legacy that’s given an education to today’s designers: luxury is empty until its cultivated from a life well lived.

Making a house is creating. I make houses like others write poetry, make music, or paint. A house is more of a likeness than a portrait. Don’t be intimidated by audacity; be audacious, but with taste. You also need intuition, originality, vigor. Avoid reproduction, that easy and banal method. Don’t get taken in by fashion. A secret: love your house.

Madeleine Castaing (1894-1992)