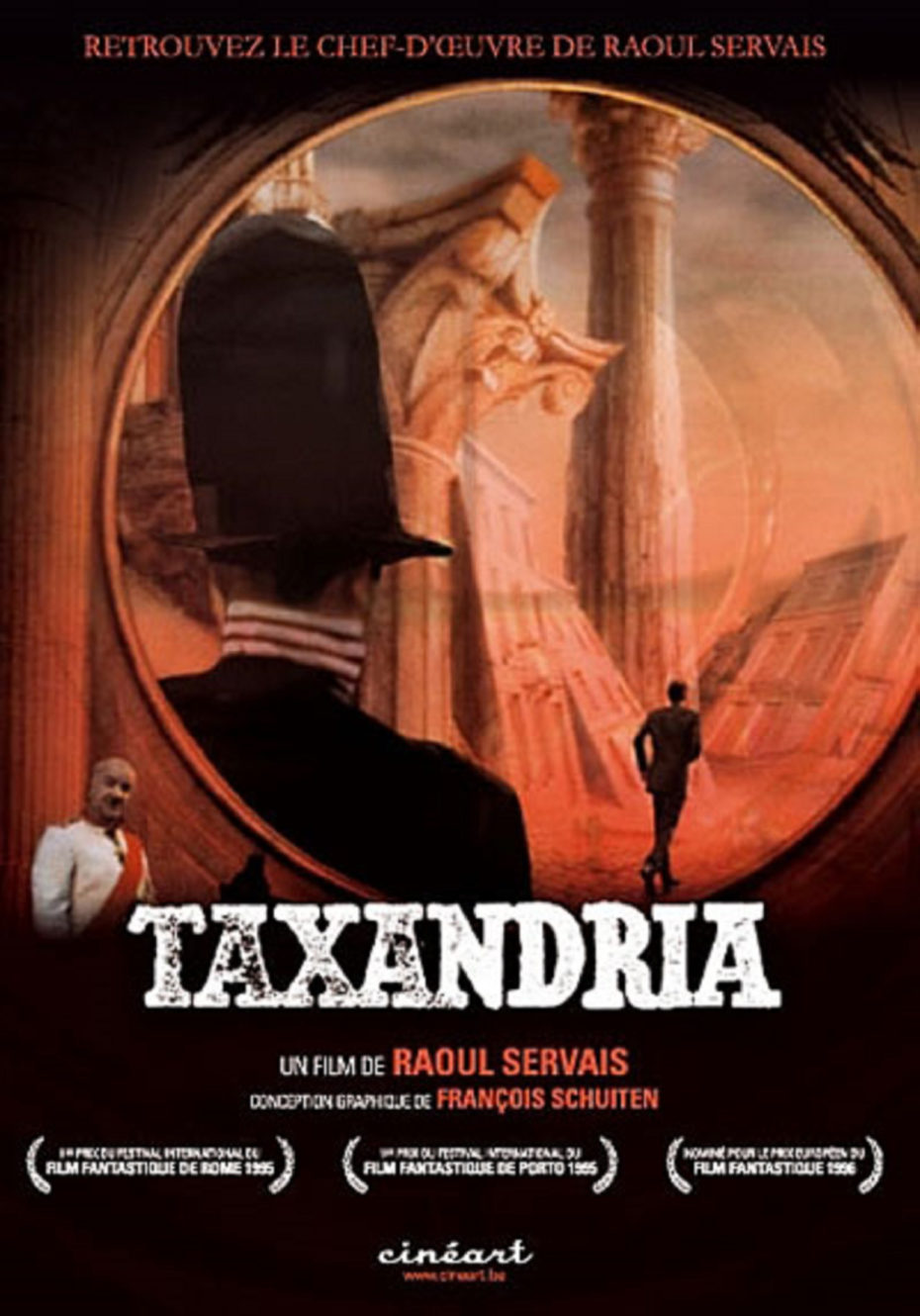

Our dreams have always remained an ineffable, un-shareable experience – the kind of thing we can describe, but never quite convey to the fullest. Then, we saw Taxandria. The 1994 film by Belgium’s Raoul Servais is the closest we’ve felt to stepping inside a world that feels just as slippery, strange, and intuitive as our dreams. Not only because it was born from the brain of a Surrealist filmmaker of Magritte’s inner circle, but because it pioneered trippy animation techniques that created a world apart from reality…

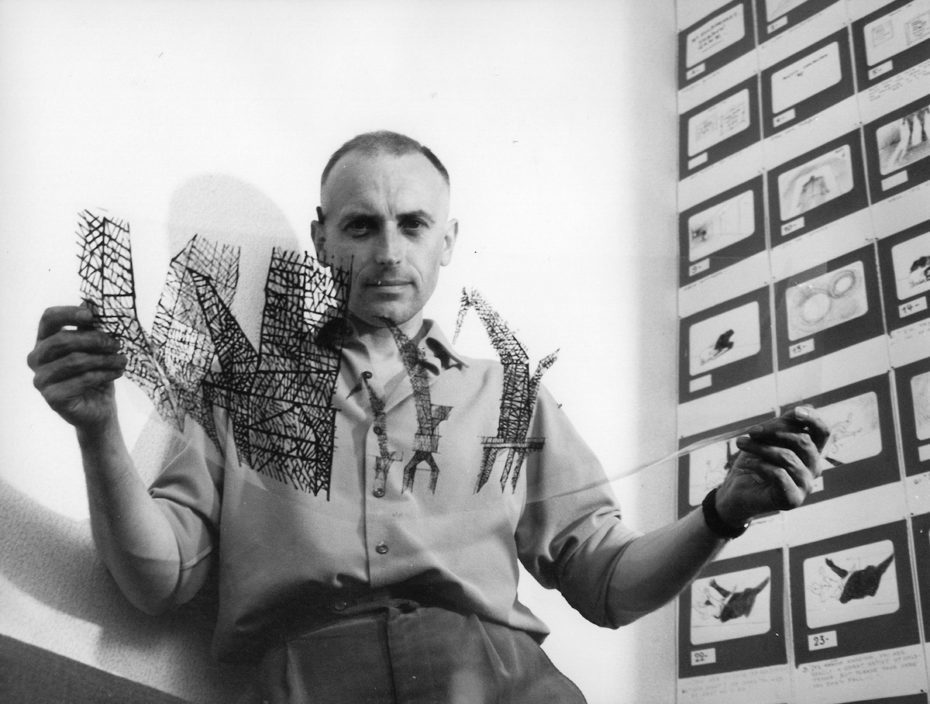

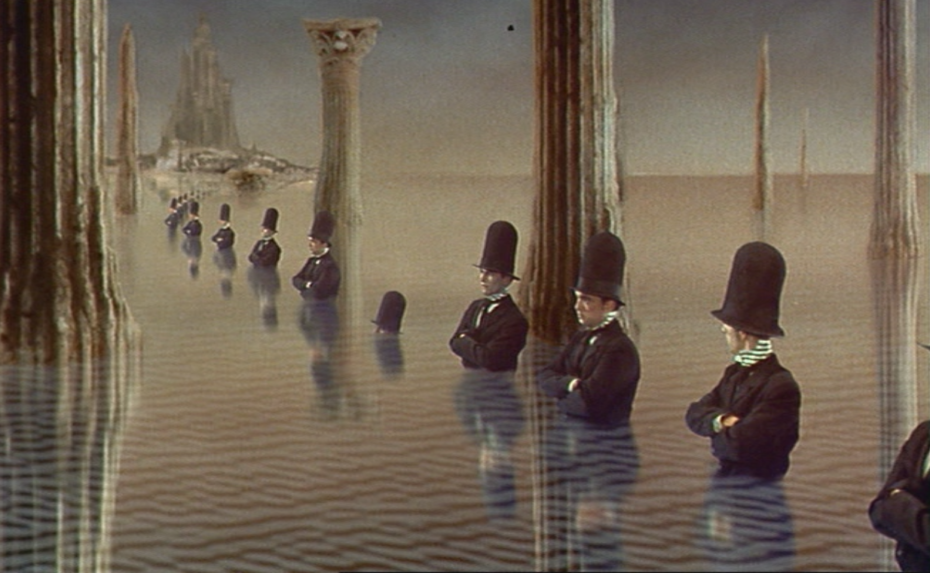

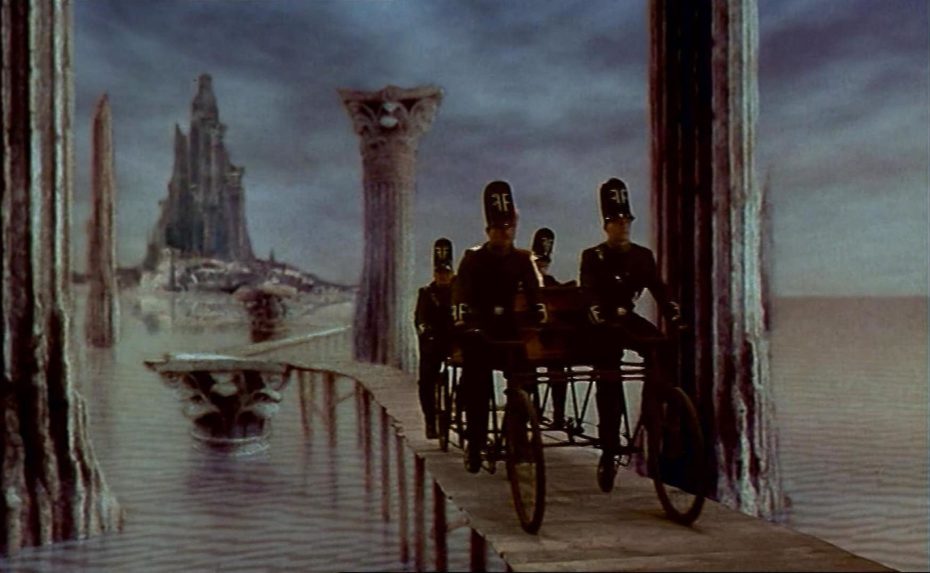

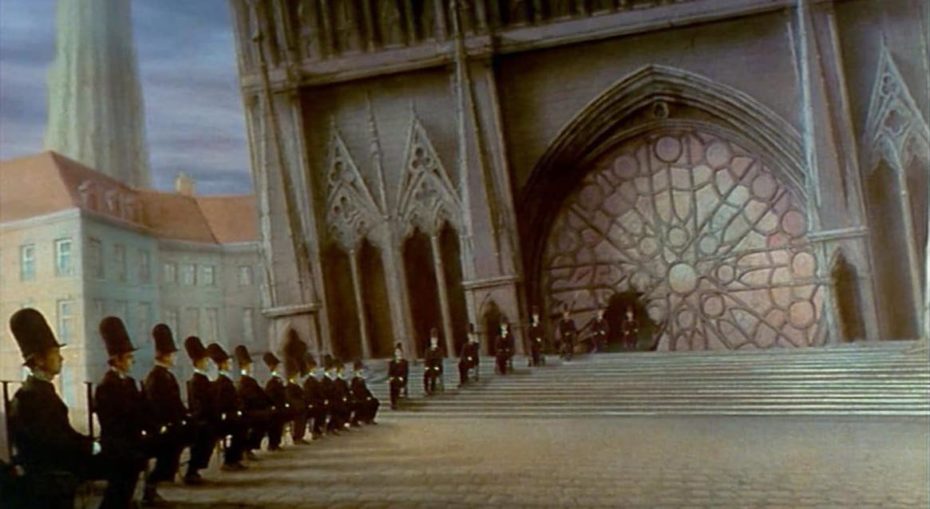

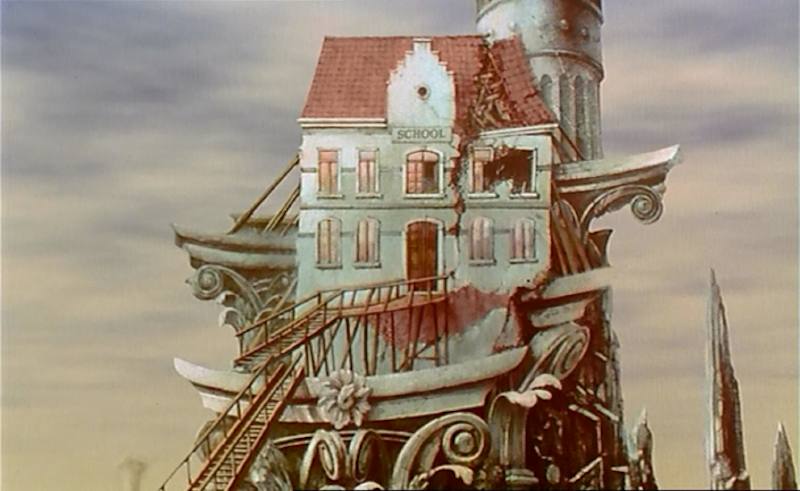

Glance at a still of Taxandria, and you’re likely to think you’ve found a vault of long lost Surrealist paintings – which wouldn’t be completely inaccurate. Servais was heavily inspired by the Belgian surrealists, including Magritte, Ensor and Paul Delvaux and brought their paintings to life in Taxandria. The film perfected his technique of “Servaisgraphy”, a mixing of his own animation, as well as live images and actors.

“I created [the Servaisgraphy] system [for the whole film],” Servais said in an interview, “though, for various reasons, it was only used for the sets. The compositing itself was done using computers. Unless I am mistaken, until Toy Story, Taxandria used more digital images than any other feature film.” The movie was filmed in Budapest in 1989, but took five years in post-production until it was ready for release.

The plot of the film is rather dizzying: an eccentric lighthouse keeper shows a curious young prince the way to the kingdom of “Taxandria”, where everyone lives in a state of the “eternal present”, wherein no technological progress can be made as per the local dictator’s decree. They have no past or present, women are kept away from men and everything is stifled by a bloated absurd, Kafkaesque bureaucracy. The Prince meets an inventor named Aimé who dreams of flying away, making new inventions and yearns to learn about his country’s past. Love, time, the black humour of endless bureaucracy – they’re all fodder to be picked apart through Servais’ gaze…

The whole thing is a mood board of dystopian Art Nouveau, bendy buildings reminiscent of Christopher Nolan’s 2010 Inception, and steampunk fantasy. You may also notice a similarity to the work of fellow Belgian artist François Schuiten’s Obscure Cities (Les Cités Obscures). As it turns out, François was the film’s production manager. In fact, throughout Schuiten’s cult graphic-novel series, characters refer to the vanished city-state of “Taxandria” which was accidentally removed from the planet during a failed scientific experiment.

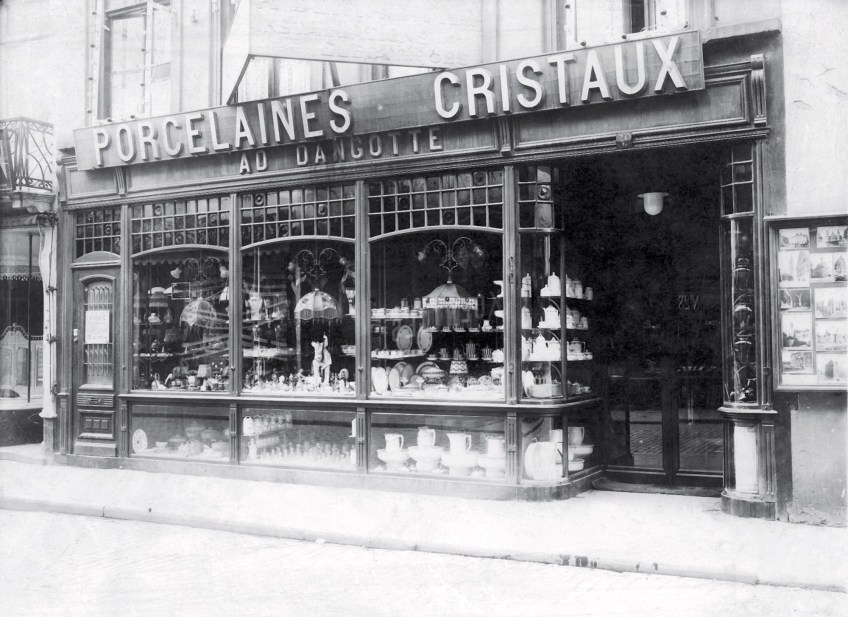

Taxandria may have come out in the 1990s, but the seeds for its message were sewn in Servais childhood in Ostend, Belgium. He was born and raised inside the a fine crystal and porcelain boutique owned by his charismatic father.

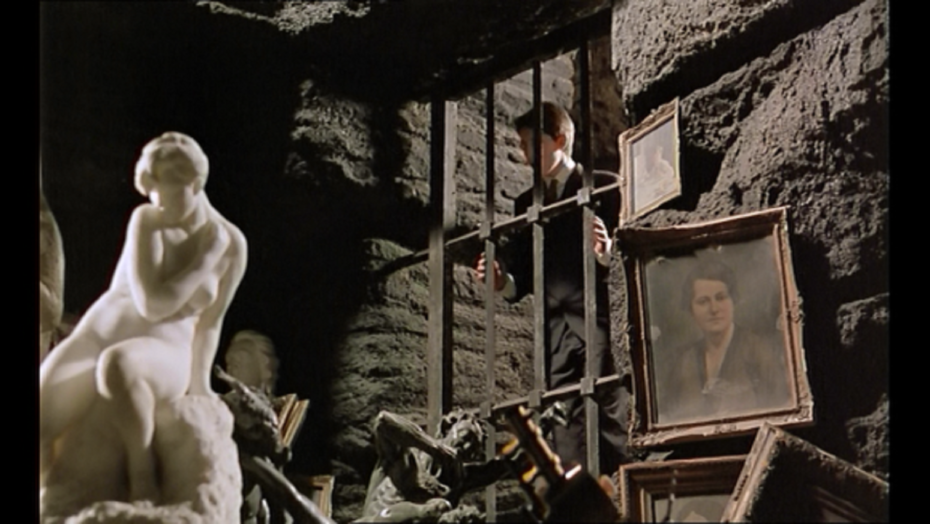

It was located in a larger, 18th century building that had been broken up into various commercial units, but once upon a time, his father said, Napoleon Bonaparte stayed there when visiting local troops. “The halls of the house were full of mystery,” explain’s Servais’ estate, “There were huge basements, and even a secret passageway. A world of fantasy unfurled before him.”

Together with his dad, Servais would make tiny table projectors and watch Felix the Cat cartoons on Sunday. The whimsy and imagination of those years spent in the crystal shop is clearly echoed in Taxandria’s fantastic, if not broken, architecture…

If the crystal shop years gave Taxandria its whimsy, then the effects of World War II coloured its decline into a dystopia. The family shop was bombed, and the business never recovered. Servais’ fantasy world endured, but it was shell shocked, running a shade darker than it did before. He studied applied arts at the Fine Arts School of Gand, where his creativity exploded; posters, murals, stained glass, tapestry – he dabbled in everything, especially film, and found a mentor in René Magritte. In the years to follow, his artistic style developed into a vision that’s equal parts fantasy and terror.

At its core, says Servais “the basic message [of Taxandria] was retained: a warning against intolerance and authoritarian ideology.” Most critics don’t know the film, which received little publicity abroad, but it has gained a small cult following over the years. As for the big question: is it any good? If you’re in a creative rut – look no further for fresh inspiration. Unfortunately it’s not on Amazon Instant Video, Netflix, or Hulu. But it has been wonkily uploaded to YouTube! Enjoy: