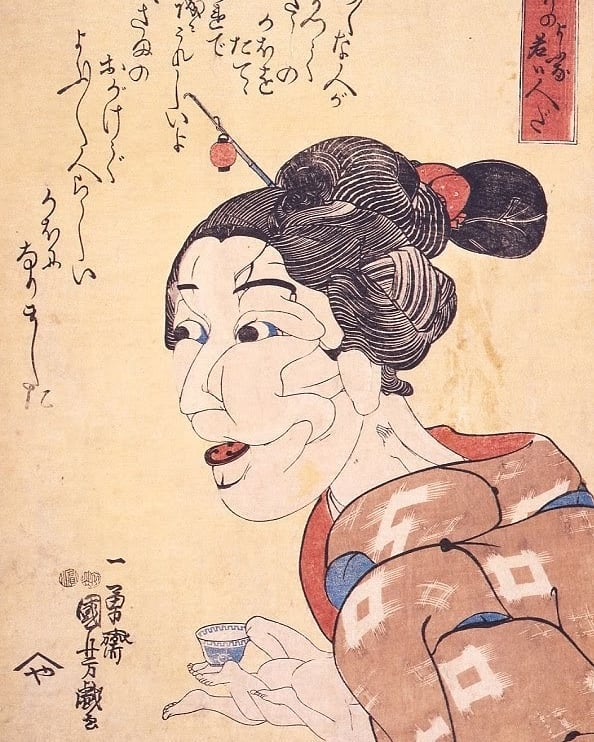

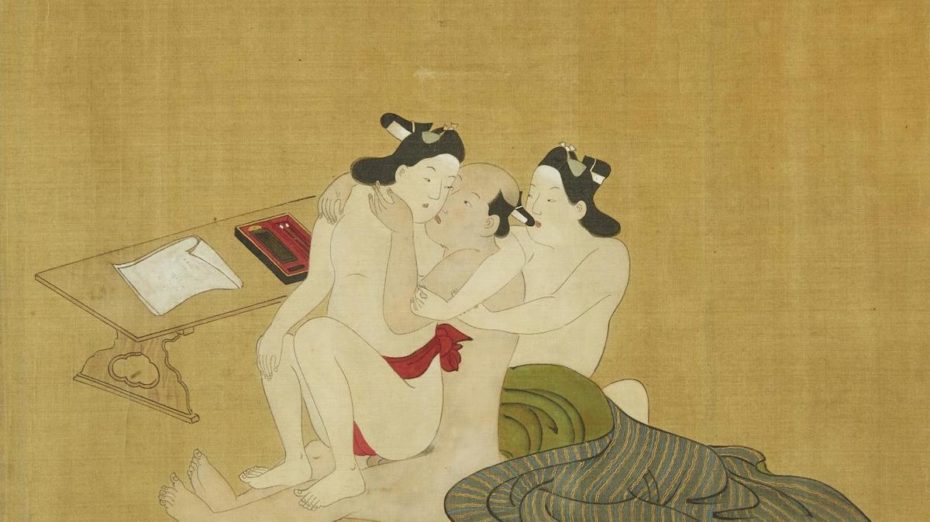

At a glance, the picture looks perfectly innocent: a 19th century, posh portrait of woman sipping tea. Upon closer examination, we learn she’s made up of entangled copulating bodies. Welcome to the fascinating world of ye olde Japanese erotica. Known as “shunga” (春画), the genre flourished in the Edo period (1600s-1800s), and the artworks didn’t just dabble in the strange, niche and fetishised realms of erotica. They rejoiced in the diversity of pleasure: shunga could be non-binary, funny, and tender; historical, luxurious, and even spooky. Though they varied in surrealism, they always fought the same, commendable battle: showing that sex and pleasure was worthy of nuanced narrative. As such, it opened up a wacky, inclusive place for Japan to get hot and heavy…

Shunga, which literally translates to “Picture of Spring” (and a classic sex metaphor) was a blanket term for Japanese erotica, which, as we’ll see, can turn from fairly tame to utterly bonkers in the blink of an eye. Historians can trace it as far back as the Heian period (794 to 1192 A.D.), but it was the dawn of Edo Period’s woodblock print that made owning art, and thus, good ‘ole smut, a possibility for folks everywhere on the social ladder.

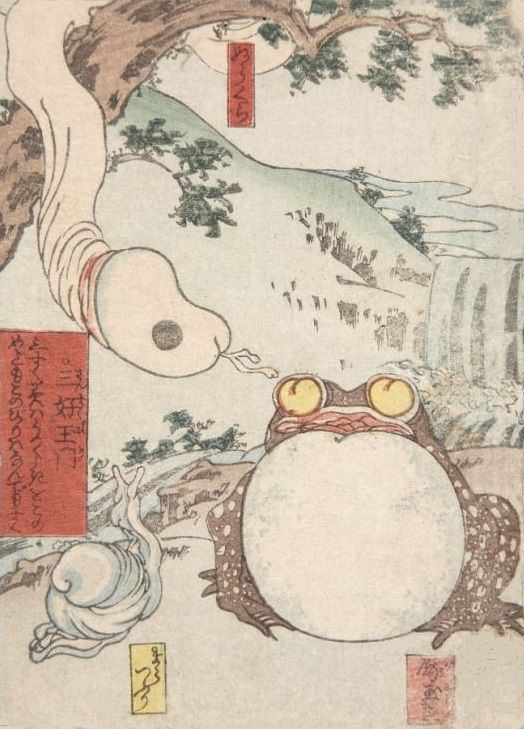

Even if you’ve never heard of the Edo Period, you’ve likely seen one of its most iconic woodblock prints, by Katsushika Hokusai – but here’s another one of the great Hokusai’s famous works, this time of the shunga genre. Be warned: this one really rips the band-aid off for our ensuing journey into shunga insanity, so hoisten your eyeballs in their sockets:

At first, shunga was only available to the upper crusts of society, but as cheaper production and wider distribution got underway, it was able to hit its famously, eherm, eclectic stride and blossom in accordance with its growing, diverse audience. There was truly something for everyone when it came to the art form. Into some old school, courtly love? You got it. Seeking snake phalluses, octopuses, and skeletons? Shunga had something for you, too.

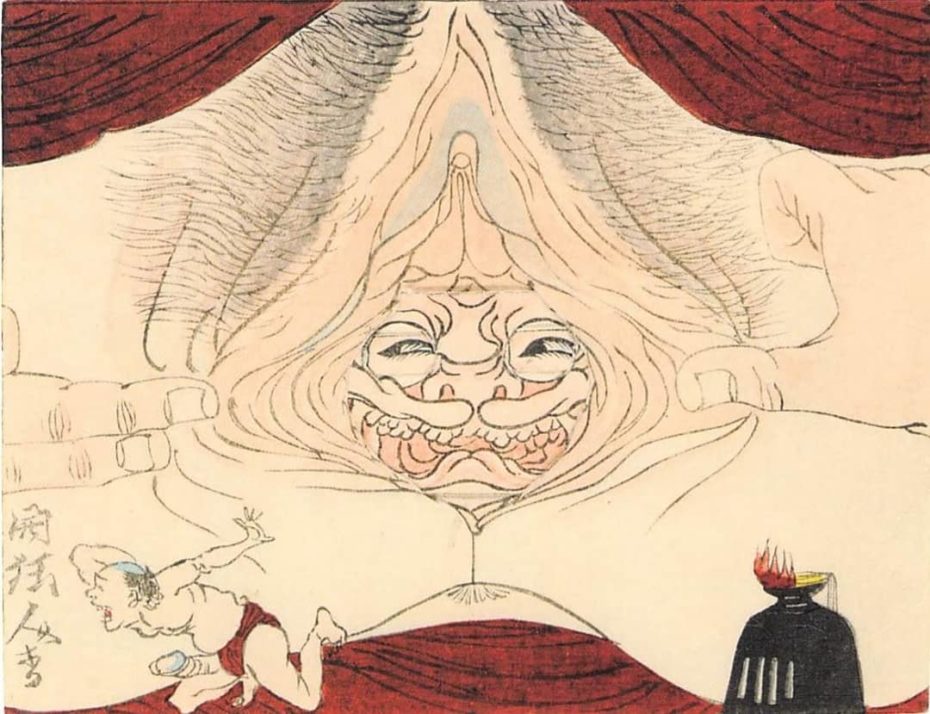

Often, it f und ways of retelling ancient myths and parodying current events. Blabbering politicians, haughty courtesans, fabled sea monsters and gods – they all found their way into shunga, especially at the hand of the artist Utagawa Kuniyoshi, one of the last greats of the ukiyo movement. His 1836 collection, Ghost Stories: Night Procession of the Hundred Demons was populated with a world of mind-boggling demons depicted in the form of genitalia.

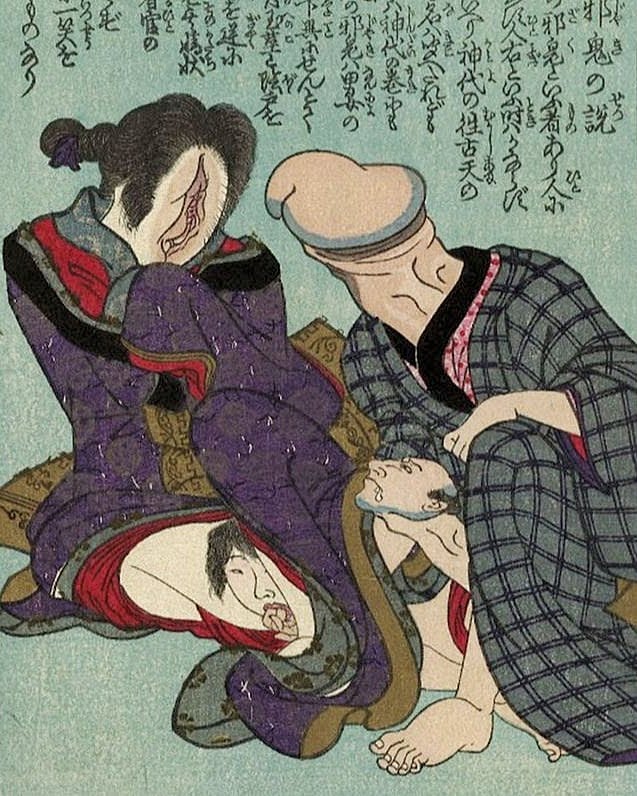

Shunga even lent itself to wartime propaganda by, shall we say, “reconciling” the sparring parties:

Why was the highly stylised erotica taking off so quickly? Well, largely thanks to the dawn of the Edo Period, which was kind of like antique Japan’s peak “Viva Las Vegas” years – and the city of Edo, AKA present-day Tokyo, was the epicentre of it all. The Tokugawa Shogunate had risen to power, uniting the previously warring clans. Suddenly, peace was the word. Samurai got day jobs. A new school of art called cstarted preaching the concept of an imagined, “floating world” (the literal translation of the word) in which hedonism, style, and intellect were interwoven. It all played out in the Yoshiwara Red Light District, through its colourful cast of Kabuki theatre actors, Geishas, brothels, bathhouse goers, and artists. For all of its ridiculousness, the delicate brushstrokes of shunga still encapsulate the preciousness of that sexual and cultural renaissance.

Most shunga artists used fake names until the 18th century until printing censorship laws relaxed. Most were made by men, but they were also marketed towards women and given to brides-to-be as almanacs for self, and shared pleasure. In that sense, they were seldom pigeon holed into a notion of sex for sex’s sake, but meant to nourish a person’s life on multiple levels; often they were considered good luck charms, believed to keep fire at bay, and a soldier safe in battle.

It’s impressive enough to see the two ends of the erotica spectrum co-flourish, from the niche tentacle fantasies to visions of generic courtly love. But things get even more interesting when we consider that female and male queer couples, as well as a kind of third gender, wakashu, were represented. This latter category was an especially curious aspect of life in Edo Japan, as the wakashu were (typically young) men who took on a non-binary gender role to please both men and women in erotic contexts. Male to female cross-dressing was also prevalent, from the streets of the Red Light district, to the stages of Kabuki theatres.

With the rise of photography shunga began to lose its intrigue for the public. The onset of Western influences in the 20th century also ushered in a wave of heteronormativity, and an exotisized gaze that wrote it off as nothing more than confusing pillow-book smut. Still, the legacy of shunga on erotica, both written and graphic, has proven immense with the passing of time. Writers like Henry Miller, Anaïs Nin, and D.H. Lawrence took many notes from its range and narrative depth. The art form’s capacity for story telling, as well as humour, was so much more than a party trick: it helped jump start open conversations on sexuality.