It began with a glance, as so many love stories do. Bernard Boursicot was your average, unremarkable accountant at the French Embassy of 1960s Beijing. Shi Pei Pu was anything but forgettable, a rising opera star in the city who enraptured her soon-to-be lover, and eventual father of her child after a chance meeting at a party. Soon, the wheels were in motion for happily ever after – until they not only came to a screeching halt, but fully derailed. Suddenly, the headline, “Chinese Spy Pretends to Be Woman, Fools French Man” dominated the papers, unveiling a shocking truth: for decades, Boursicot and Pei Pu had been spies for the Chinese government – and Boursicot not only claimed ignorance to the espionage, but to the fact that Pei Pu was a man all along. In the decades since, many have tried to untangle the intricacies of this lovers’ scandal. How could Boursicot not realise Pei Pu was a man? What about their supposed child? Time has made their saga no less fascinating, but it has turned it into the kind of snapshot we never thought we’d have of China’s history: a cautionary tale of its transition into communism as it related to the creative, gender, and sexual identities of those inside its borders.

There’s actually a term for the kind of ruse Boursicot found himself in, one many of us have seen played out in 007 films: a “honeypot trap” of enemy seduction. Bond, of course, rolled fatal love affairs right off his shoulders. But Boursicot was no Bond, and understanding who he was before he moved to China is crucial to understanding how he became such a prime target for a honeypot trap…

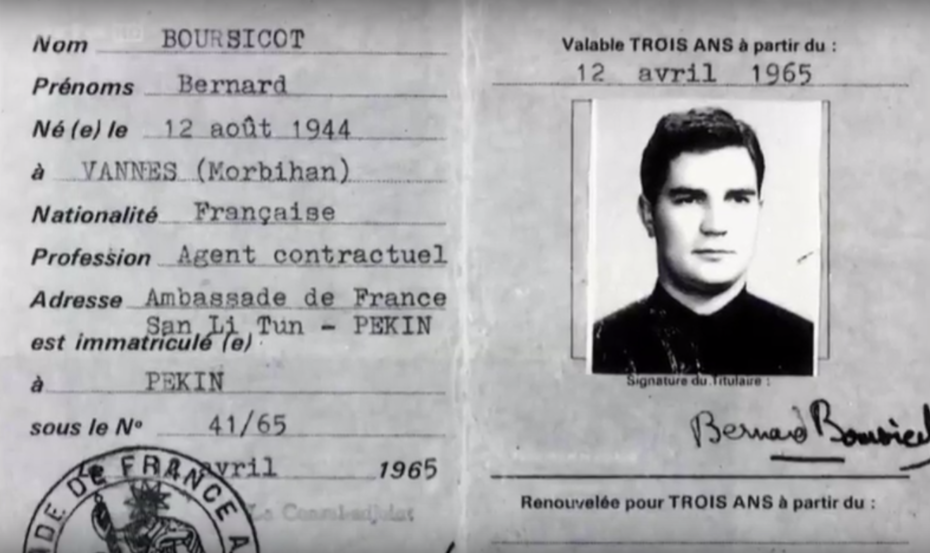

Boursicot, who now lives in a nursing home in his native Brittany, was a provincial boy with daydreams of the Amazon jungle. A lover of art and cinema, he moved to Paris and became friends with the legendary late cinephile, Henri Langlois, who could tell Boursicot was ready for adventure, and told him to apply for a job opening at the French Embassy in Peking (current day Beijing), China. It was a small gig, but one that would allow him to live out his travel dreams on the exotic stage of ‘the Orient’. He leaves for China immediately.

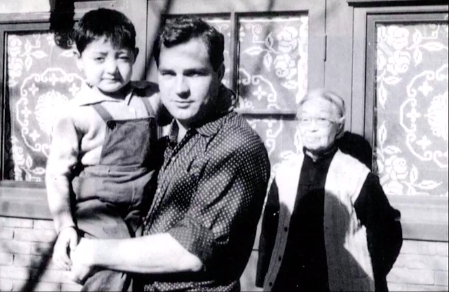

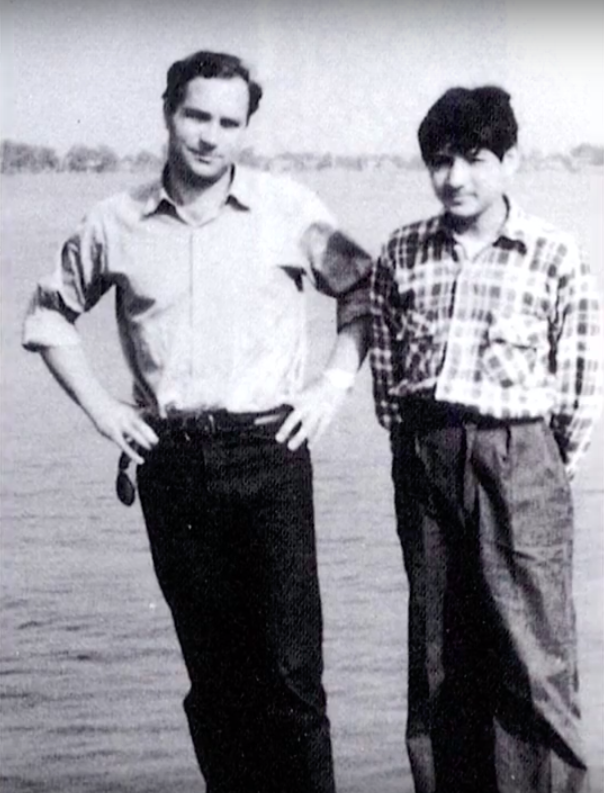

You could argue that Boursicot was built for self-deception. Naïve, and romantic. A high school dropout, but a voracious reader. He wasn’t very articulate, and didn’t have many friends – let alone lovers. When he arrives in China in 1964, the 20-year-old doesn’t know what to make of his environment, but he’s intoxicated by it all – the language, the landscape, the locals. “I felt like I was on another planet,” he told the French-German television chain, Arte, in 2016. The Peking Opera embodied all of that romance, opening up a world of stories, songs and characters unlike anything he’d known back in Brittany. Notably, its rising star Pei Pu.

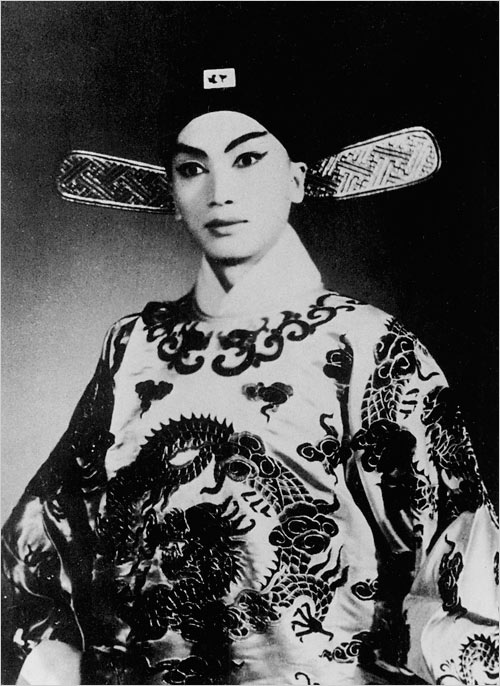

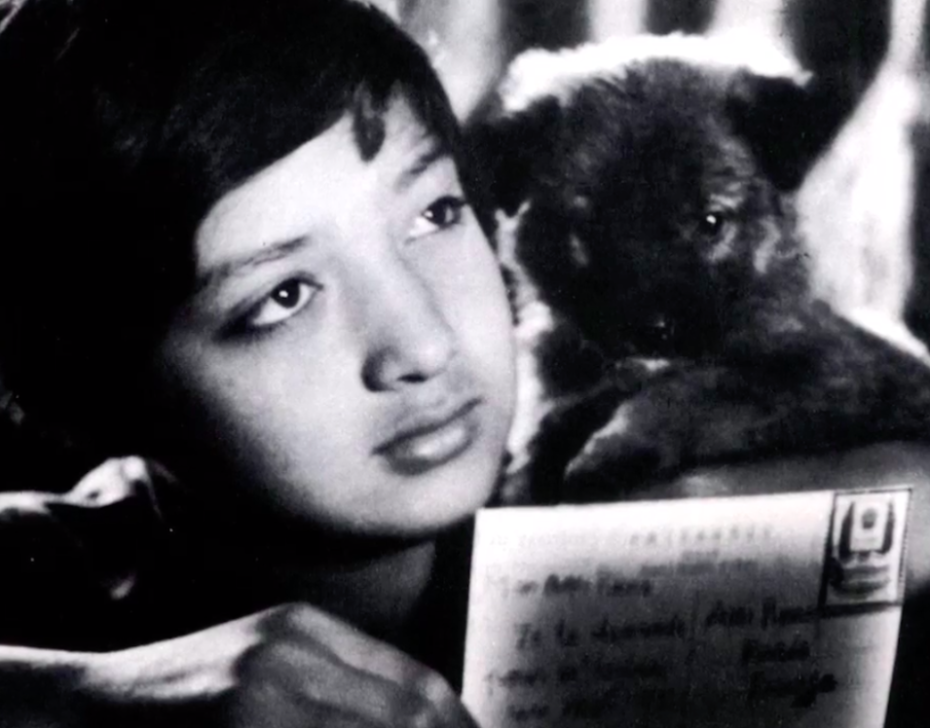

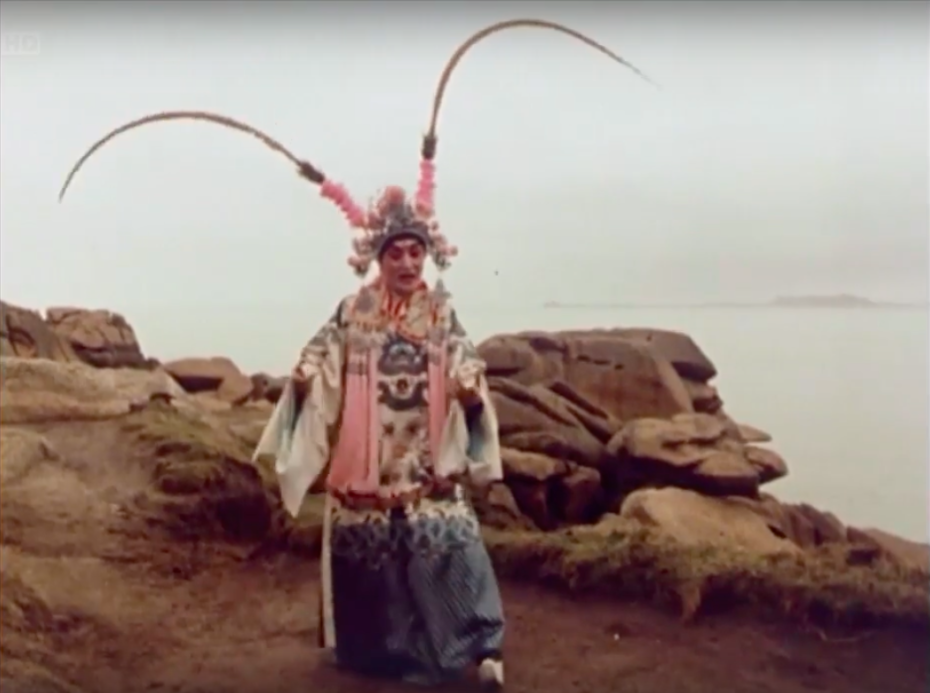

“She didn’t dress like everyone else,” Boursicot explained, “She was particularly seductive, and a wonderful storyteller”. She was witty, and spoke fluent French. After introducing herself to him at a Christmas party, Pei Pu tells him her life is a lot like that of the famous Madame Butterfly – an opera she says she’s starred in – because, like the title character of the play, she also has to shift between disguises: a woman by nature, but a man by disguise. Why? Boys, she says, are more valued in traditional Chinese culture, so she often adopts the appearance of a man in public. Boursicot believes her, and a romance unfolds.

Lest we tangle the details: at this point, we have a man pretending to be a woman pretending to be a man, to seduce another man who may also be gay. In later interviews, Boursicot vaguely explains that his first and only sexual encounters were brief, and with men, before changing the subject. Pei Pu meanwhile never confirmed what exactly his/her/their gender identity was – but it was likely fluid. In one 1988 interview, Pei Pu explains, “I used to fascinate both men and women. What I was and what they were didn’t matter,” and in another, says, “I never told Bernard [Boursicot] I was a woman. I only let it be understood that I could be a woman. I thought France was a democratic country. Is it important if I am a man or a woman?” The closest we can come to an intimate understanding of Pei Pu, says playwright David Henry Hwang, was that “he was, above all, a performer”.

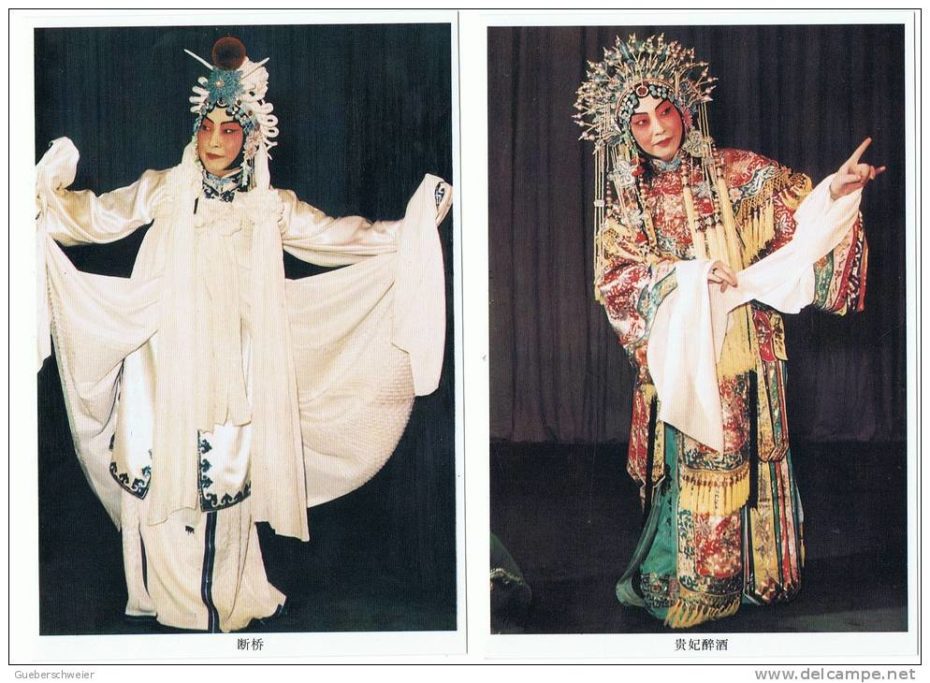

Hwang later composed the Tony-award winning Broadway musical, M. Butterfly about the Boursicot-Pei Pu scandal. “When I offered a percentage of the play’s royalties to its real-life inspirations,” he told Time in 2009, “Shi instead demanded a recital at Carnegie Hall, a wish as grand as it was unfeasible”. Pei Pu’s identity and gender were inextricably bound to his showmanship, or at least to the kind of creative expression the world of the stage offered. Almost always, female roles were played by men in Chinese theatre, carving out a public space for gender ambiguities to be explored and celebrated. “It was sad because in China, homosexuality was frowned upon,” Pei Pu later said, “I had two professors who fell in love: later, the one who was the ‘lady’ was beaten to death.”

When Boursicot and Pei Pu meet, it’s at the dawn of a new age for China. Mao Zedong’s brand of communism squandered those who lived on the fringes of society. Individual expression was diluted through a sieve of Red Book-appropriate propaganda. Thus, when Boursicot arrives, he’s fascinated by what he sees as a new, neutral gender norm: short hair (for men and women) is the rage, and the plain “Mao Suit” is the country’s new uniform.

After just a few months together, Pei Pu tells Boursicot she’s pregnant. The news falls rather serendipitously, just as Boursicot is fired from his job at the embassy. The two are heartbroken, Boursicot later recalls in interviews, and when he calls Pei Pu in tears from the airport, she assures him she’ll still be there, waiting for him to return. After all, they’ll have a child to raise.

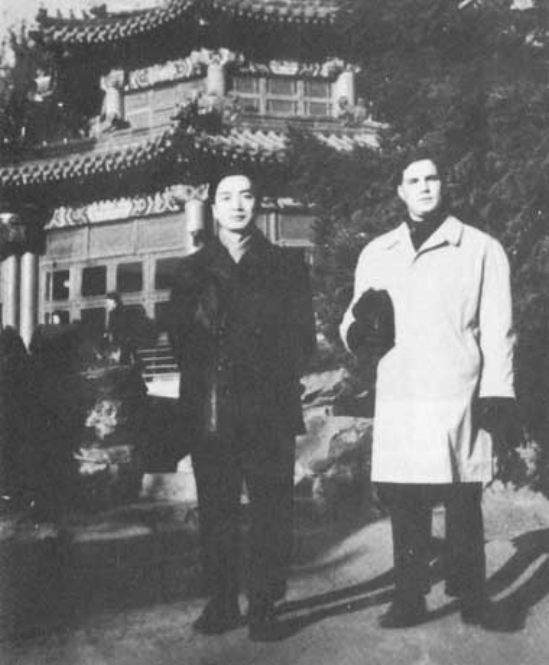

Boursicot stays in contact with Pei Pu, who tells him their son, a now four-year-old named Shi Du Du, has been sent to a village by the border of the USSR for safekeeping during the Cultural Revolution. A photo of the boy is enough to assuage his questions – little “Du Du” even looks like him. When Boursicot returns to Beijing, the tension in the air between the Red Guard and foreigners is nearly tangible: China was closing its gates to the rest of the world, and Boursicot got in by a hair, if that. Over the following years, he’d have to take a job at one of the hardest French Embassy posts ever, at a village in Mongolia (where the winters reach -40 celsius) just to be able to take the train in to visit Pei Pu in Beijing.

At this point, Bouriscot had been asked by Chinese officials to relay documents from the Embassy to two officials on a regular basis, using his relationship with Pei Pu as leverage. Bouriscot willingly, even enthusiastically, agreed, and over the next decade he quietly shuffled thousands of documents back and forth. “For me, it didn’t feel like betrayal,” he said, “It felt like I was serving China. I still don’t understand that…how can sharing information between two countries you care for be harmful? I felt I was helping each one.”

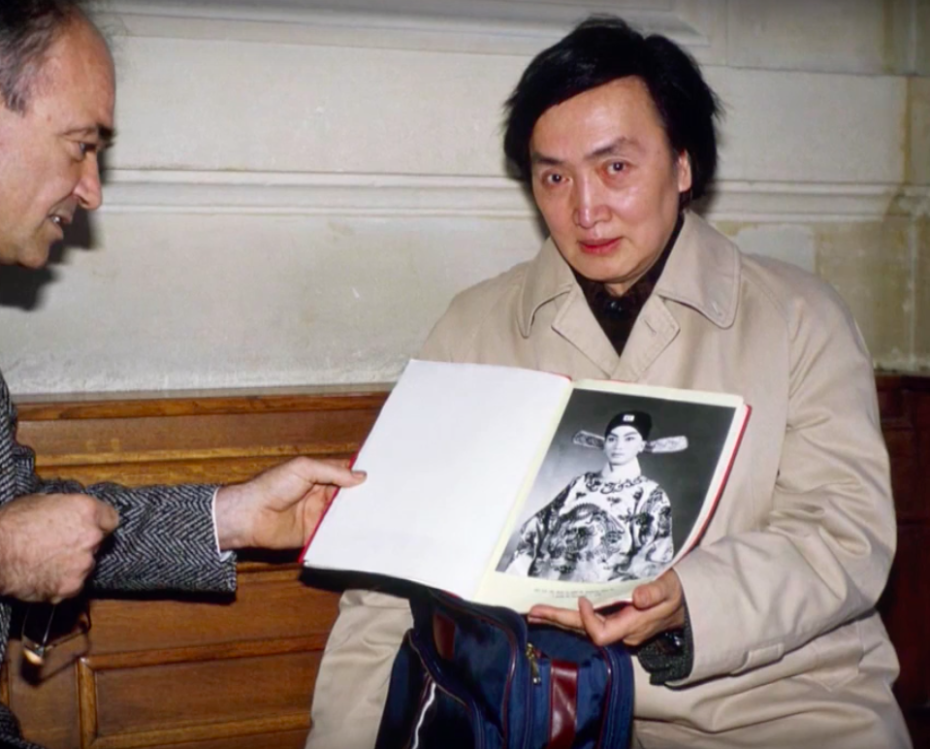

After decades of media interviews, it’s now clear that Boursicot and Pei Pu had reached a more platonic relationship when he was stationed in Mongolia, and that Boursicot enjoyed a number of relationships with men and women. His visits to Beijing, authorised every six weeks, were primarily to visit the young Du Du. Then, in 1982, the family of three finally came to Paris. At first, things went smoothly – Pei Pu was welcomed as “Monsieur Shi” and given opportunities to perform in theatre and on French TV, becoming a bit of a celebrity:

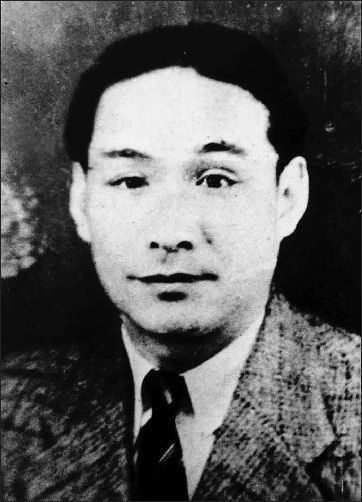

The Direction de la Surveillance du Territoire became suspicious of Bouriscot and Pei Pu’s relationship, questioning them and ultimately bringing them both to trial in 1986 for espionage. Pei Pu said she’d no idea Bouriscot was relaying documents, only that he’d meet the same man outside of her home in Beijing for “lessons about Chairman Mao.” Bouriscot also appeared flabbergasted. The real shock, however, came when a court-ordered physical examination proved that Pei Pu not only had male sexual organs, but that the young Du Du had been sold to the Chinese government by his poverty-stricken family to play the role of Bouriscot and Pei Pu’s child. Both men received a six year prison sentence. Pei Pu was pardoned after one year due to health complications. Bouriscot, still behind bars, attempted suicide.

Bouriscot said he had honestly believed Pei Pu was a woman, if not because he was so in love with him for so many years. The court’s defense argued that his lack of sexual experience, combined with Pei Pu’s ability to “tuck” his man bits, made this fantasy a liveable reality, particularly once Du Du was thrown into the mix. “I know, I know, in the newspapers I am this fat, stupid man who made love to a woman for 19 years and did not know,” Boursicot told tabloids, “But this is not the way it was. And when I believed it, it was a beautiful story.” Don’t forget, this is during an era where people still believed Liberace just “hadn’t met the right girl yet”.

The media blitz was relentless, painting Bouriscot into either a thick-headed pervert or a cunning spy, even when his defense proved that “[the] case is absolutely at the bottom of the ladder in the spying world,” with many of the “classified documents” having been low-grade catering requests, or details on upcoming theatre productions like Carmen. “I like to think I’m the hero of this story,” Bouriscot said, “even if I’m an idiot hero.” In 1993, a thorough investigation by The New York Times showed that he had given his entire life to Pei Pu. Rolex watches, fancy electronics – loving Mr. Madame Butterfly was quite the expense, even aside from the cost of espionage. Pei Pu, by contrast, held his own with interviewers, consistently justifying his actions by saying he simply let Bouriscot see what he wanted to see. It wasn’t a hard task for him. “I got the nickname ‘Jade Beauty’ [in the theatre],” he said, “because I was so cold.”

Pei Pu lived out his days as an opera singer and voice coach in Paris until his death in 2009. He and Boursicot spoke on occasion, but not often, with the latter finally coming out as bisexual. Little Shi Du Du still lives in Paris, but Boursicot now lives in an assisted centre in Brittany, longing for those early days in China, even after everything he’s been through. “I hope to go back,” he told reporters in 2017, “I miss it.” His story no longer belongs soley to him – it’s moved on to Broadway, even to Hollywood. It’s become a vehicle for expression about the fatal power of love, survival, and the lies we sometimes tell ourselves in order to live.