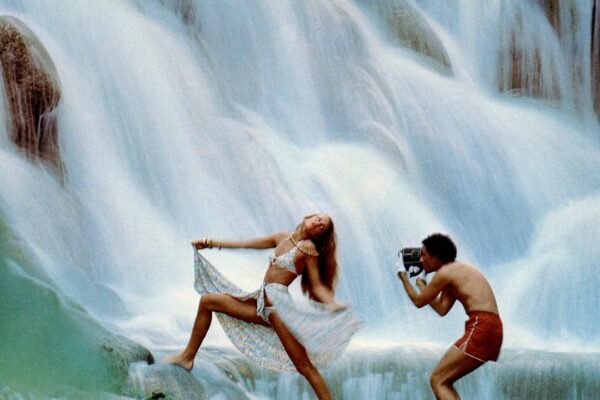

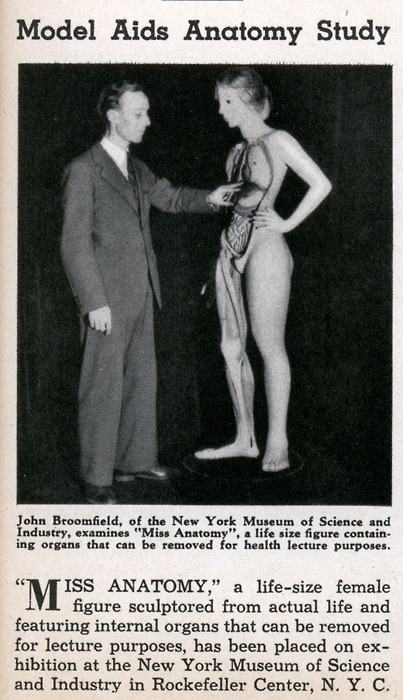

The summer of July 1932 brought an unexpected guest to Brussels, Belgium. The city had become its usual, ephemeral playground for the oddities, treasures, and inventions of the Foire du midi annual fair, but this time it was joined by the curious Dr. Spitzner and his posse of wax humans. The production of dissectible, anatomical figurines had peaked in Europe during 18th-19th centuries, fascinating medical students and public spectators alike as not only tools of science, but a perverse beauty. Consider the crown jewel of Spitzer’s collection, la Vénus méchanique: her hair, perfectly coiffed, spilled over her shoulders while her chest rose and fell with a “breathing” function. Her expression wasn’t lifeless, but serene. Sometimes, she wore a nightgown. She was forever stuck in the disturbing intersection of science and aesthetics…

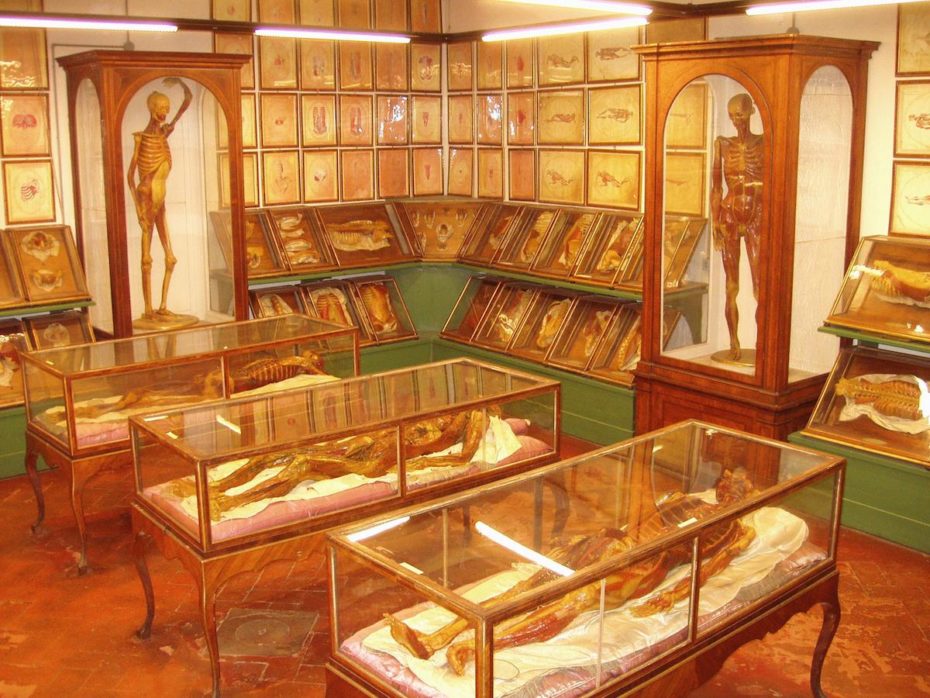

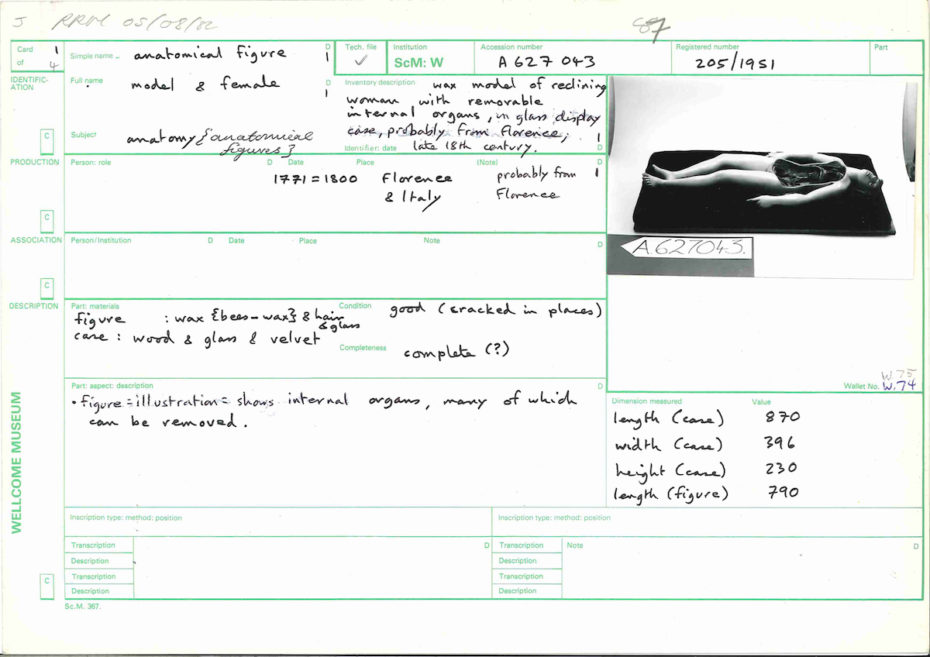

Wax figurines have been used in medical study since the Middle Ages, but wax artists Celemente Susini and Felice Fontana really upped the ante with the birth of the very first Venus, circa 1780. The figure was commissioned by the Grand Duke of Tuscany as the cherry on top of La Specola, Florence’s first public science museum, and a wild wunderkammer that lives on today; its antique halls house not only the Venus and her waxy kin, but the Medici family’s dead pet hippo. But we digress.

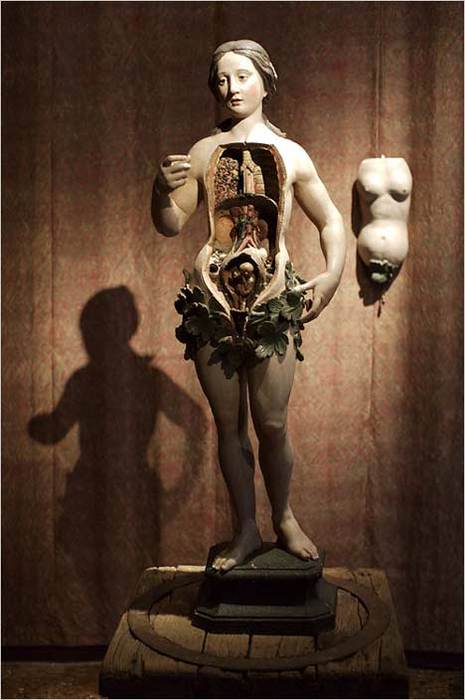

You could say that Susini and Fontana’s Venus offered a means of looking death in the face without truly confronting it. The reasoning was both practical, and ethical; up until the Renaissance in Europe, dissection in the name of science was tricky moral territory for doctors. The Venus, and the throngs of doppelgängers she inspired, was sold as a compromise. Instead, it enabled some rather problematic practices…

In her excellent book, Anatomical Venus, art historian Joanna Ebstein explains that these figures were “adorned with glass eyes and human hair and can be dismembered into dozens of parts revealing, at the final remove, a beatific foetus curled in her womb.” Their backs often arch upwards, as if in a state of ecstasy. The women’s appearances were always Botticelli-worthy, crafted just as much for medical reasoning as they were artistic enjoyment. If a Venus was ‘lucky’, she might even wear a pearl necklace. Today of course, the idea of a female body ‘performing’ for the male gaze, even in death, is chilling at the least, but hardly unfamiliar.

We were curious to know how La Specola presents the figure today, and their site lists the following: “The agony of a young woman is represented in her last instant of life as she abandons herself to death voluptuously and completely naked. The thorax and abdomen can be opened, allowing the various parts to be disassembled so as to simulate the act of anatomic dissection.”

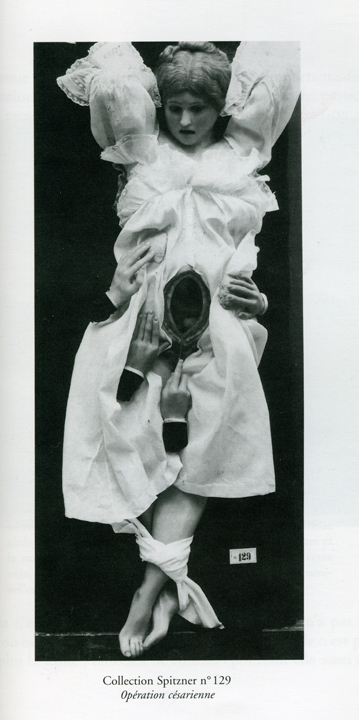

The dangers of marrying sensuality (i.e.”voluptuousness”) with science is the reinforcement of harmful gender norms. These Venuses are always white, complacent, and depicted as weighing under 60kg. They’re spooky, ye olde Stepford Wives, and over time they’ve fascinated everyone from the Marquis de Sade, to the iconic Italian writer Italo Calvino, who wrote an essay in 1984 on the absurdity of a mid-Cesarean Venus from the Spitzer collection, titled, “The Museum of Wax Monsters.”

Calvino called it, “the most incredible example of sadist-surrealist fantasy…[the] model of a patient lies with her eyes wide open, her hair impeccable, her calves tied together, dressed in a long, lace nightgown, which is open only at the part of her body which has been cut open by a scalpel, where the baby appears. Four male hands are placed on her body: fine wax hands with manicured nails, ghostly hands since they are not supported by arms but adorned only with white cuffs and with the ends of the sleeves of a black jacket, as though the whole ceremony was being held by people in evening dress.” Sounds like a scene from the brain of Magritte or André Breton, n’est-ce pas? The wax Venus also fascinated the late Belgian painter Paul Delvaux…

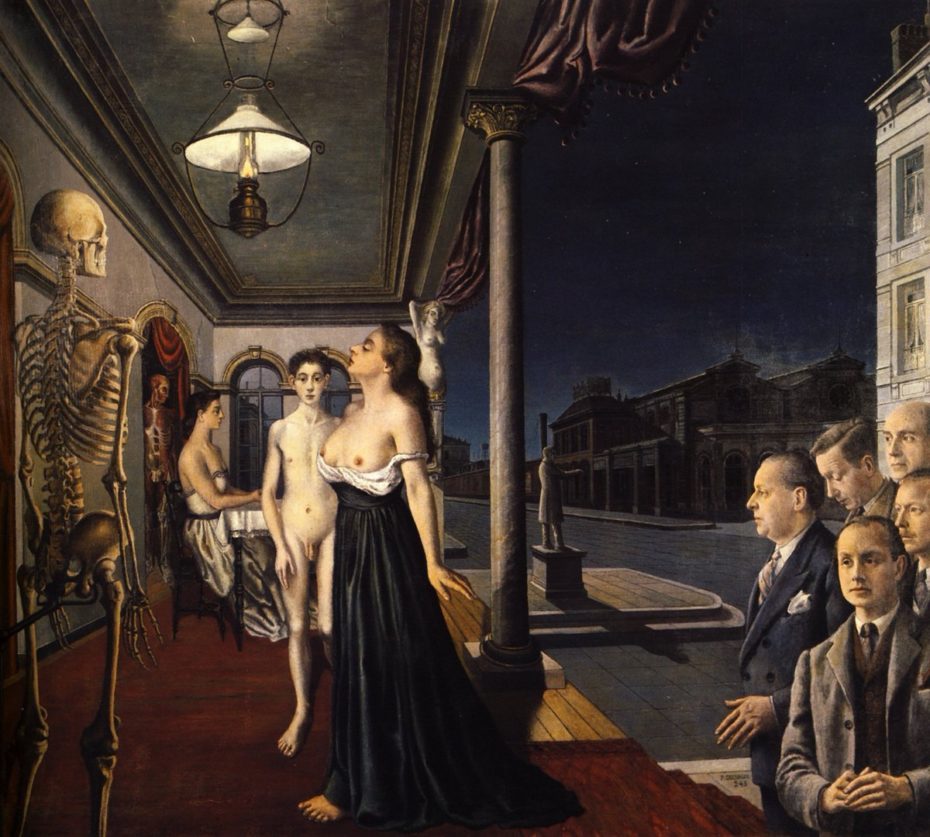

Belgium has always had a flair for the fantastic. It was home to whimsical illustrators and comic book creators like Hergé (Tintin) and François Schuiten (this amazingness), and gave us Surrealist painters like Magritte and Delvaux – the latter of which was obsessed with Spitzner’s Mechanical Venus. Delvaux made regular pilgrimages to see the Venus and the skeletons, which became haunting fixtures of his work:

Over the course of his life, Delvaux would create (and destroy) many canvases dedicated to what he called his “Sleeping Venus” character, fashioned after the mechanical model. Traditionally, Surrealism has been a boys’ club. (Just ask André Breton.) Delvaux didn’t speak nearly as much at length about his issues with women as Breton, but he did become obsessed with an idea of the “unobtainable feminine” when his mother forbid him from marrying the love of his life, Anne-Marie Maertelaere. Enter the big mommy issues, and dark motifs around women and maternity; for Delvaux, a woman resigned – even inactive – was a woman at peace.

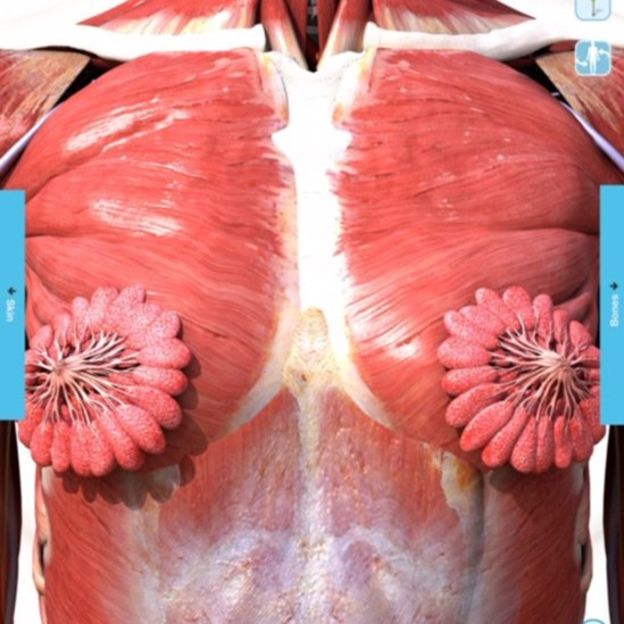

Today, our anatomical models don’t don pearl necklaces. But there’s work to be done on the front of de-stigmatising the female body, as evidenced by the Internet’s collective freakout after a rendering of a female muscular system, complete with milk ducts, went viral on Twitter in April, 2019.

The image has since been proven to have some inaccuracies, but the dialogue it sparked was moving, as people realised that diagrams of the male muscular system were ingrained their brain as the “default” form of, well, being human.