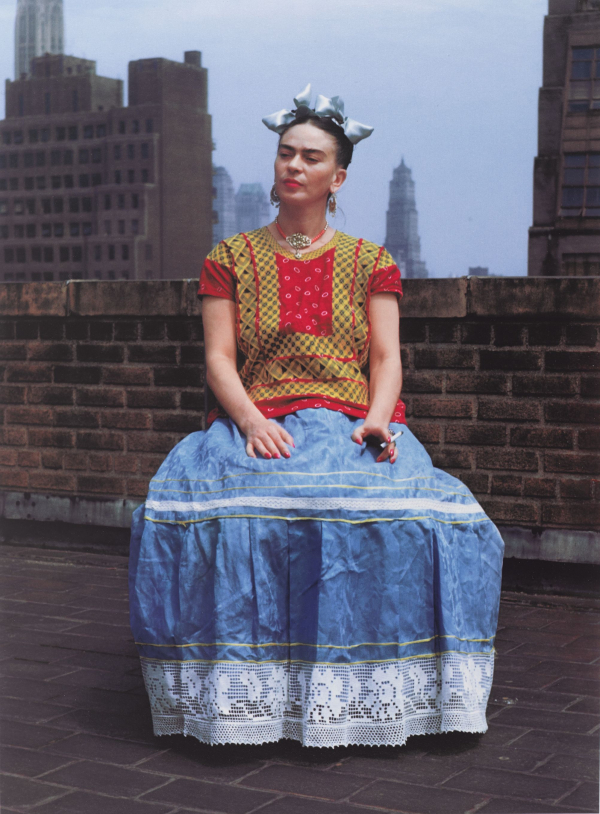

As the 1930s, the Frida Kahlo gained international notoriety as “Diego Rivera’s wife”, gracing the cover of French Vogue. Then, she floored the avant-garde scene with artworks whose vulnerability spoke from the heart while their rawness punched you in the gut. The public ate it up, despite not always knowing how to digest it. Posthumously, and especially in recent decades, her popularity has blown into full on “Fridamania. Frida “merch” exists in almost every corner of the world, with much of it made by heartfelt, amateur artisans. But more of it, is now coming from retail behemoths like Forever 21, Mattel and most recently, the sneaker brand Vans, which released a limited edition collection of shoes inspired by some of the painter’s most iconic works. More than a cult, Frida is now a corporation – literally – and we wanted to find out a little more about what that really means.

We should probably mention: We love Frida and we are consumers of her likeness. We own a “Frida unibrow” mug. At the MessyNessy HQ in Paris, you’re greeted by a Frida Kahlo beaded bamboo curtain over the doorway. Why? This may be a shot in the dark, but for anyone in need of an extra dose of you-can-do-it creative energy, Frida is the perfect cheerleader. She was also the unofficial, patron saint of misfits; “‘I used to think I was the strangest person in the world,” she once said, “Read this and know that, yes, it’s true, I’m here, and I’m just as strange as you.”

Lovely words. Nice enough to print and package up in a nice poster online, which is exactly what’s been happening ever since Etsy and Pinterest took off in the past decade. Here she is on a pair of customised huarache sandals handmade in Zapopan, Mexico:

The shoes, writes shop owner Jorge Zamora, are made by local “artesanias mexicanas.” Thus, a customer’s business also supports the small businesses and artisans of Kahlo’s beloved Mexico, making it an ethical way to cash in on her memory. Then, there’s everything else: Frida sneakers and baby booties; Hawaiian print Frida shirts, and Frida leggings; Frida lamps, oven mits, and iPhone cases. There’s even a t-shirt with her head plastered over the body of fellow cultural revolutionary, Patti Smith. There doesn’t seem to be much control over her image, but that may not be the case for much longer…

“The Frida Kahlo Corporation” has been a business operating out of Panama since 2004. Kahlo had no children of her own, and the handling of her legacy has caused a rift in descendants. In 2005, her niece Isolda (inheritor of her property rights) trademarked and sold the rights to the words “Frida Kahlo,” in turn, helping to create the Frida Kahlo Corp (FKC), which has been attempting to claim total ownership of her likeness ever since, arguably even more aggressively since Isolda’s death in 2007.

On their site they declare “Frida Kahlo Corporation owns the trademark rights and interests to the name Frida Kahlo worldwide”. If you want to print a picture of Frida – who, by law, should be relatively free of copyright as she died 50 years ago – you have to go through them, as some unsuspecting independent retailers have been learning the hard way.

The FKC has been taking measures to have amateur artists removed from platforms like Etsy and issuing threats of lawsuits for the use of Frida’s likeness. Meanwhile their mission statement on their website reads: “We are dedicated to educating, sharing and preserving Frida Kahlo’s art, image and legacy.”. One Etsy seller based in Denver, Colorado who had her Frida dolls flagged and taken down from the platform due to alleged infringement of the Frida estate, has since filed a lawsuit against the corporation this summer.

“I don’t believe that artists should be bullied or threatened into abandoning their art, silencing their voices, and stifling their creativity,” Nina Shope announced on Facebook, who creates homages to Frida with folk-art inspired creations. The dolls feature her signature unibrow, but should FKC really own the legal right to a unibrow? “That is the main reason why I am challenging the FKC’s alleged trademark registration, that has been used as a cudgel not only against me but against a number of other creators and artists.”

The company’s Instagram feed, @realfridakahlo (facepalm), is filled with swish images of Frida merch, from their impressive licensing collaborations with companies like Vans to some rather more perplexing fashion choices that would have most wondering how exactly “her legacy lives on” in a knock-off (of a knock-off) handbag design that was likely manufactured in China. It’s problematic products like these that make FKC an easy target for accusations of tarnishing and white-washing Frida’s legacy.

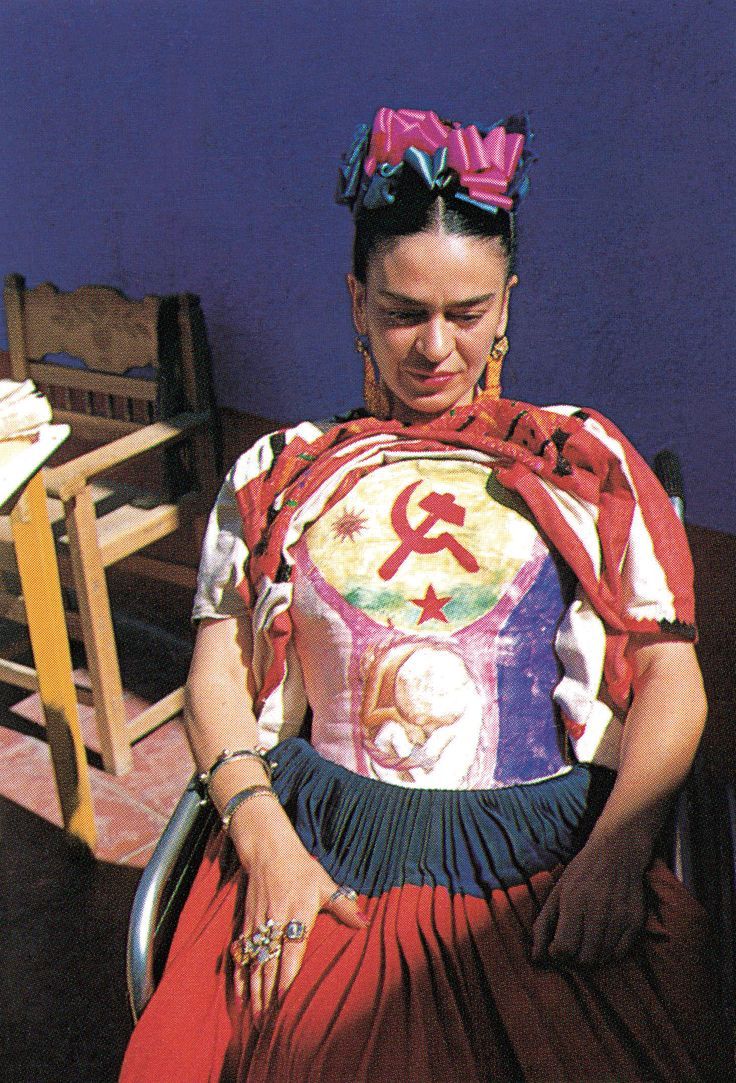

Offering a “Frida Kahlo Graphic Sweatshirt”, mega-retailer Forever 21, licensed to use the artist’s likeness by FKC, is infamous for snaking out of liability for their workers’ horrific work conditions, and $6 hourly wages at factories in Los Angeles, home to one of the nation’s second-largest Mexican immigrant community. Somewhere, Frida Kahlo, the staunch communist, is rolling over in her grave.

The most controversial collaboration occurred in 2018, with the release of a Mattel x Kahlo Corp.’s special edition, “Frida Kahlo Barbie.” The doll was thinner, whiter; with pale eyes and a barely there unibrow. Even her clothes, meant to depict traditional tehuana artistry were inaccurate. Isolda’s daughter Mara Romeo Pinedo, Frida’s grandniece – who has never been a fan of the corporation – was outraged over the doll, took it to court, and successfully outlawed it in Mexico (it’s still available in the US).

The entity claiming the right to control the commercialisation of Frida Kahlo no longer has a family connection to the late artist. Frida’s niece, Isolda, who became a co-owner of FKC in 2005, passed away in 2007, and now, the corporation is suing the family. Last year, the FKC countersued Mara Romeo Pinedo, for trademark infringement. Isolda’s daughter had set up a competing website, fkahlo.com, which doesn’t seem to be doing much at the moment, but interestingly, while FKC’s Instagram account (@realfridakahlo) is not verified, only Pinedo’s account, @fridakahlo, boasts the little blue tick by the text, “Cuenta oficial de Frida Kahlo, en memoria de la gran artista mexicana” and nearly 1 million followers. By contrast, the Frida Corporation has 3,837 followers.

In its lawsuit, the FKC asks for a court order to force Pinedo to shut down her website and social media accounts, as well as at least $75,000 in compensatory damages.

As a woman and a minority, the capitalisation of her identity sneaks into dangerous territory. On every level in which Frida has been made into a doll – not just Mattel – she’s been jammed into a cookie-cutter-mold of her former self, all the while making a profit for the kind of capitalist corporations in ways that the artist wouldn’t have wanted. It could also be argued that Frida’s mainstream stature has only made her more accessible, bringing her story and influence to a new generation of young girls. There are also some positives to be had when one goes through all the Frida Corporation’s partnerships with a fine tooth comb: the lipstick line they made with Republica Cosmetics, for example, is cruelty free. The company’s website touts an affiliation with the KFC for Culture and the Arts, a valuable scholarship source.

The jury is still out regarding the corporation’s ethics, and the ethics of owning the identity of persons in general. Still, the company continues to produce necklaces, bags, candles, and even tequila – you name it, Kahlo Corp has given it Frida’s namesake, and stuck it in every Modern Art museum gift shop.

Most recently, the corporation’s Frida Kahlo restaurant at Playa del Carmen closed after barely a year in business, suffering from devastating reviews: “the wait staff aggressively pushed alcohol, not telling them the cost … over priced and basic … ABSOLUTELY DO NOT go here … the restaurant is a fraud and pulled a colossal bait and switch.”

Kahlo’s creativity lived by its own rules. Her paintings were surreal but not Surrealist, a label she blatantly rejected given the boys club nature of the movement (and its leader, frenemy André Breton). One cannot speak for Frida, but we can look to how her passionate, firm ethics guided everything she ever did. It’s safe to say she would want fans to tap into that energy, rather than appropriate tehuana garb. She hated big cities and big industry, preferring the silent, sun baked agave fields of Mexico. “The most important thing for everyone in Gringolandia,” she said, “is to have ambition and become ‘somebody,’ and frankly, I don’t have the least ambition to become anybody.” Food for thought at the check-out line.