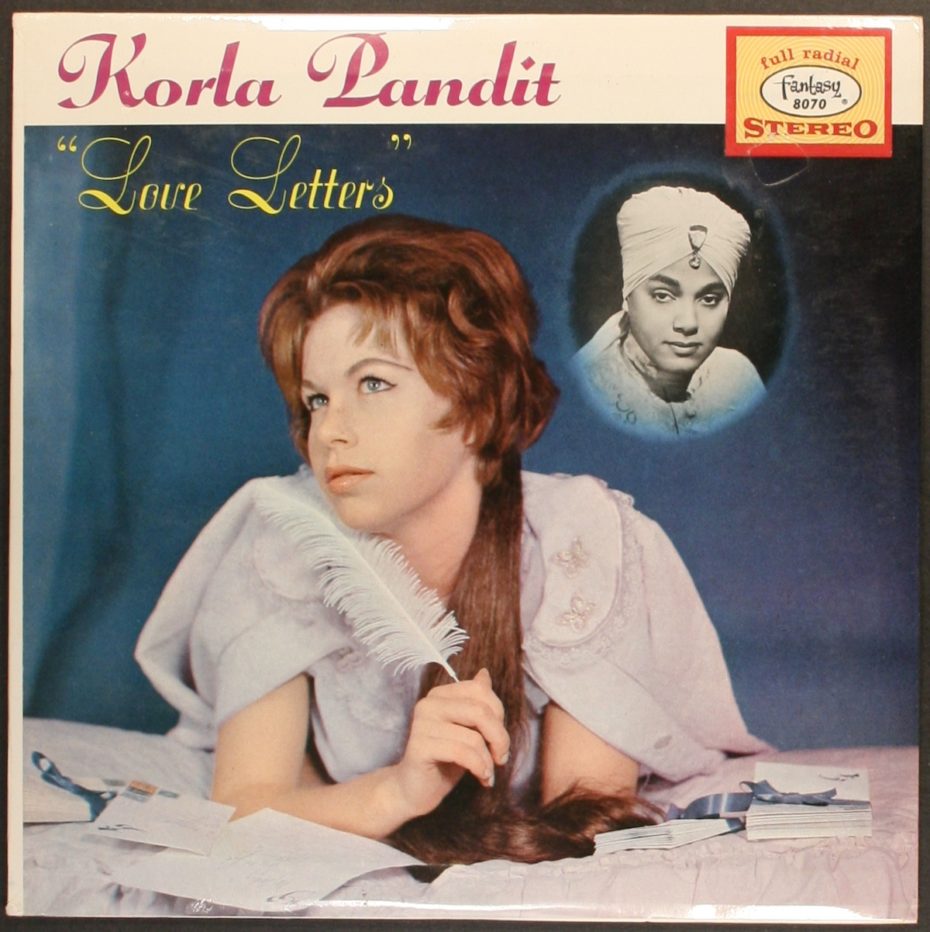

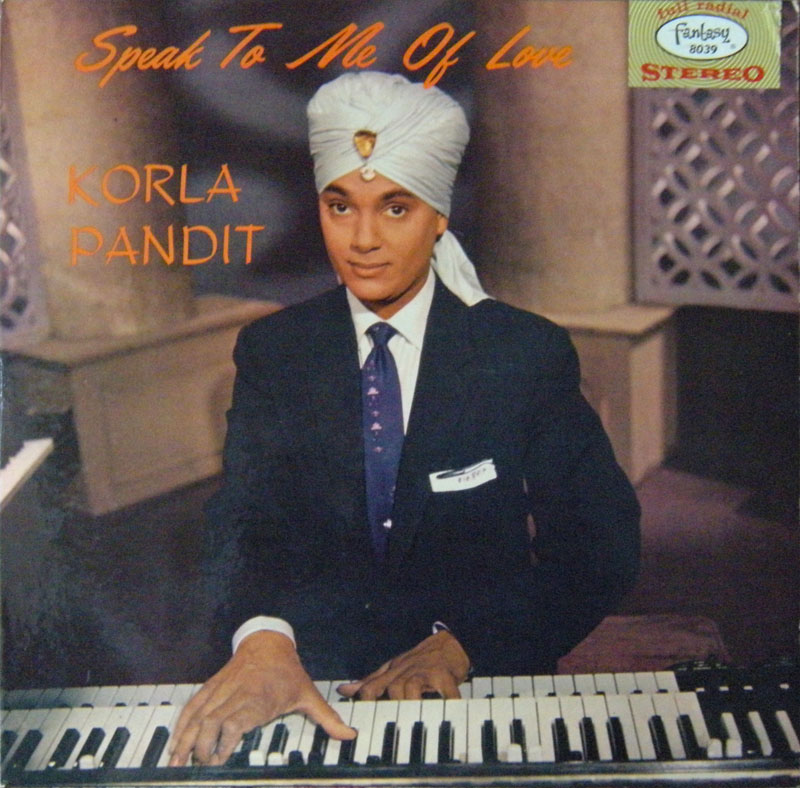

Sex sells, and it sells even better with a dash of mystery. For every housewife in mid-century America, the enigmatic charm of Indian performer Korla Pandit was the ticket to getting weak in the knees before the kids came home from school. In the 15 minutes allotted to The Korla Pandit Program, the performer brought a scintillating new rhythm to suburbia’s ho-hum beat. Every week, he’d grace the small screen and play the sultry sounds of Miserlou with a coy smile, wearing a bejewelled turban, and flashing those soul-searching bedroom eyes. It was all part of his schtick, of course, and one of the most strangest in Hollywood history, given that Pandit wasn’t Indian, but African American. Today, the persona he created opens up a dialogue about race, fame, and surprising flexibility of truth.

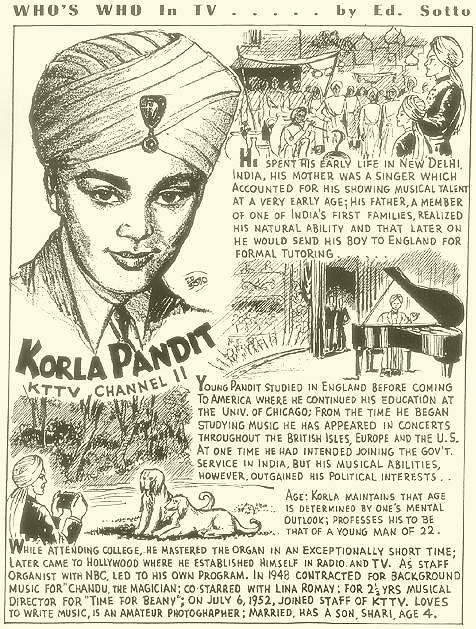

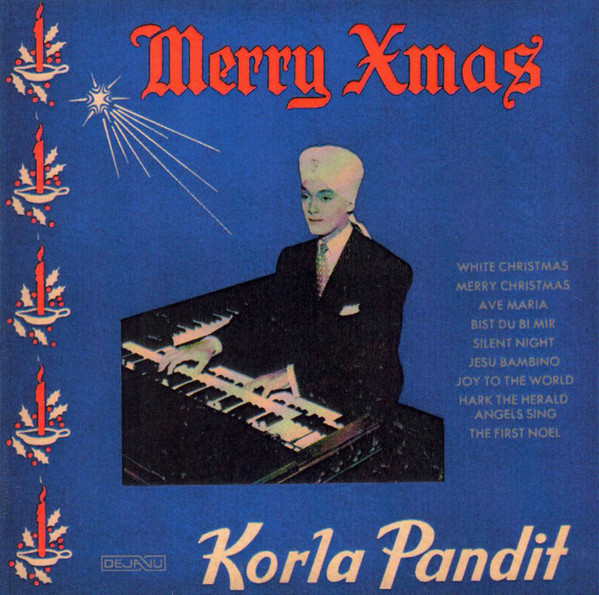

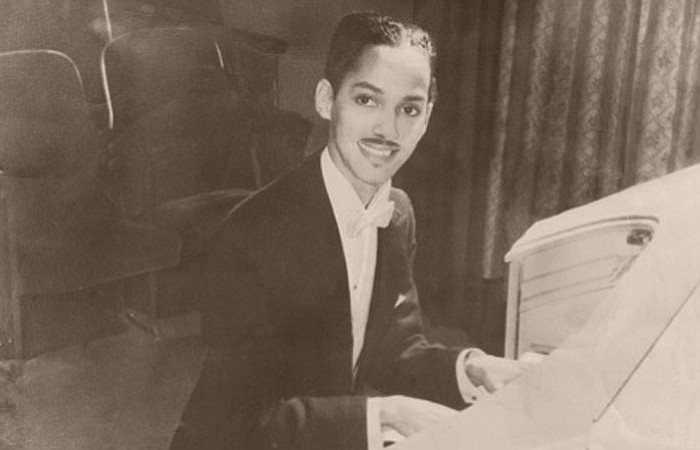

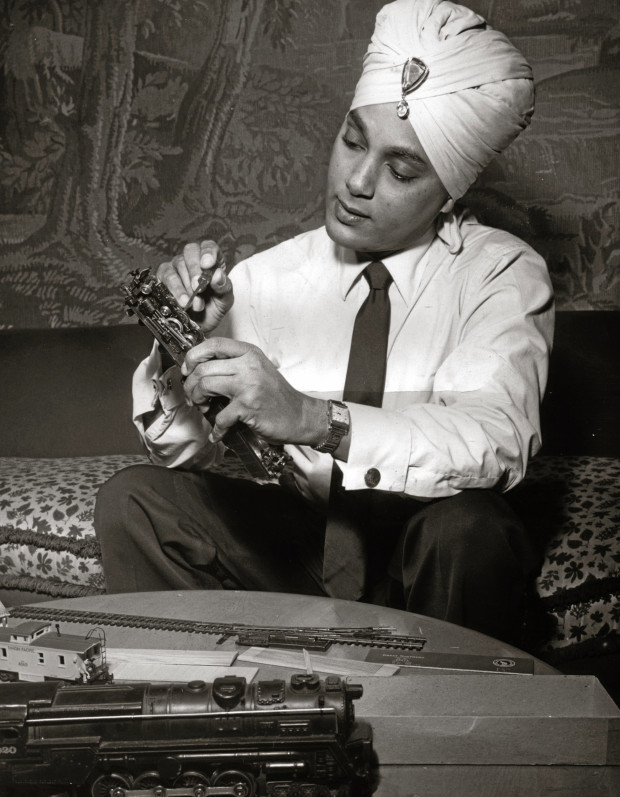

The first thing to know about Pandit, was that he was called the “Grandfather of Exotica.” Now the genre of “exotica” is very specific to post-WWII America, when daydreams of “the Orient” and Shangri-La ran wild. For decades, the performer was lauded as a genius of the genre, playing a mix of contemporary covers and his own mystical tunes. Here he is performing almost 70 years ago:

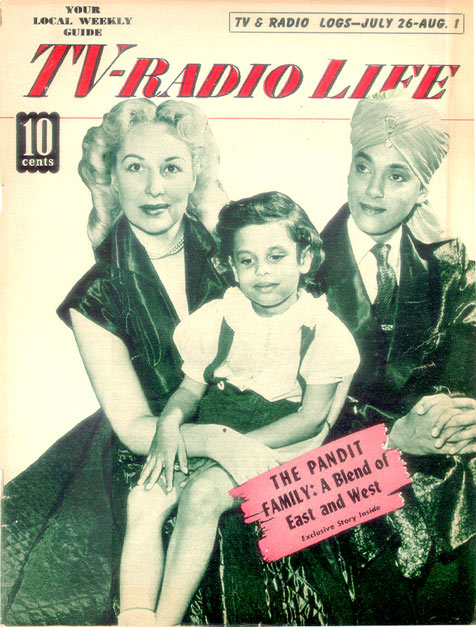

Pandit moved to Los Angeles in the 1930s, edged his way into showbiz, and finally gained fame in 1949 when his TV show premiered. Not once, during nearly 1,000 episodes, did he speak to the audience – instead, he let his eyes, and his music, do the talking. “I never spoke, yet I received letters from around the world [from] people [who] knew exactly what was on my mind,” Pandit said. “I once asked a parapsychologist if it were possible that the technology that transmitted my image and music could also transmit my brain waves and he said yes, it was possible.”

Almost overnight, “he became a phenomenon,” explains John Turner, a friend of Pandit who made a documentary on the musician in 2015. Like everyone else outside of his immediate family, Turner believed Pandit’s story – he also believed in his talent to connect with people from his core, and said “he was breaking the Fourth Wall” with a gaze that in saying nothing said oh, so much. As a 1975 article in The Independent Journal said, “[Pandit is] a puzzle inside an enigma wrapped in a turban.”

His fable was as follows: Pandit was born in New Dehli as one of six children. His father was a respected government employee, hailing from the upper ranks of India’s caste system (as a Brahmin man); he even boasted family relations to President Nehru. His mother was a famous French opera singer. “Pandit was a child prodigy,” reported The Los Angeles Times in a 1988 interview with Pandit, “[his] natural gift was nurtured with musical training in England and at the University of Chicago where he enrolled at the age of 13. His education in the ways of the world commenced in Los Angeles when he found himself part of the birth of a new form of entertainment called television.”

The exotica genre was born from a kind of messy fetishism, and Pandit was put on its pedestal. To our eyes, he seems rather demure. Still, in 1950, it was remarkable to see a non-white man host his own show – not to mention, it was a damn good one. Pandit played the organ with his hands, wrists, and elbows in a state of calm, but somehow, complete rapture. As one man in Turner’s documentary says, it tickled a special chakra.

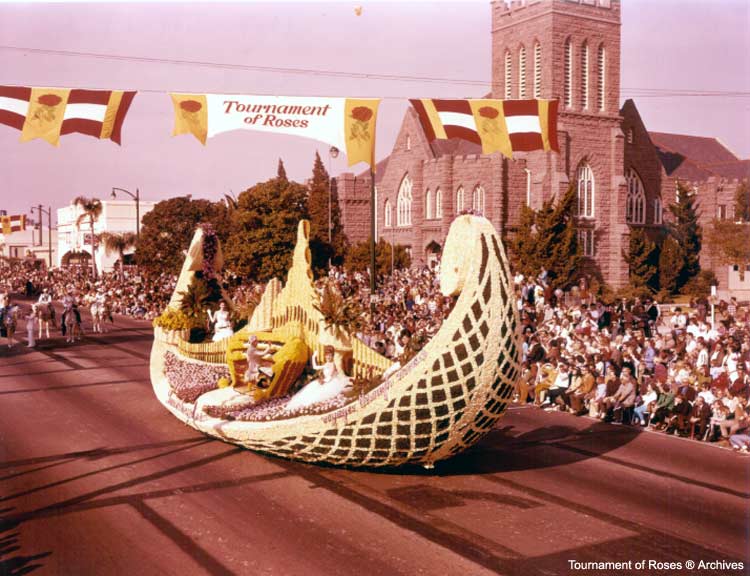

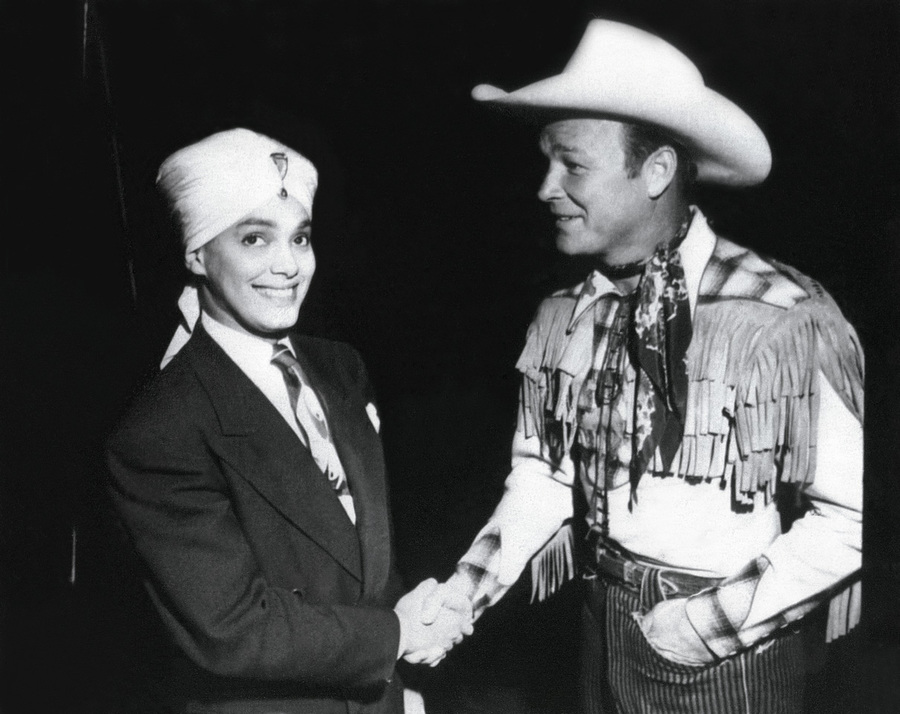

Over the next few decades, Pandit became a household name in Hollywood and beyond. He was pals with Bob Hope, Errol Flynn, as well as “fellow” cultural Indian icons like yogi Paramahansa Yogananda, and the actor Sabu Dastagir. He even got his own float at the 1951 Rose Bowl Parade, where he played an organ made out of flowers. When he finally passed away in 1998, it was still as Pandit – the role he played to the grave.

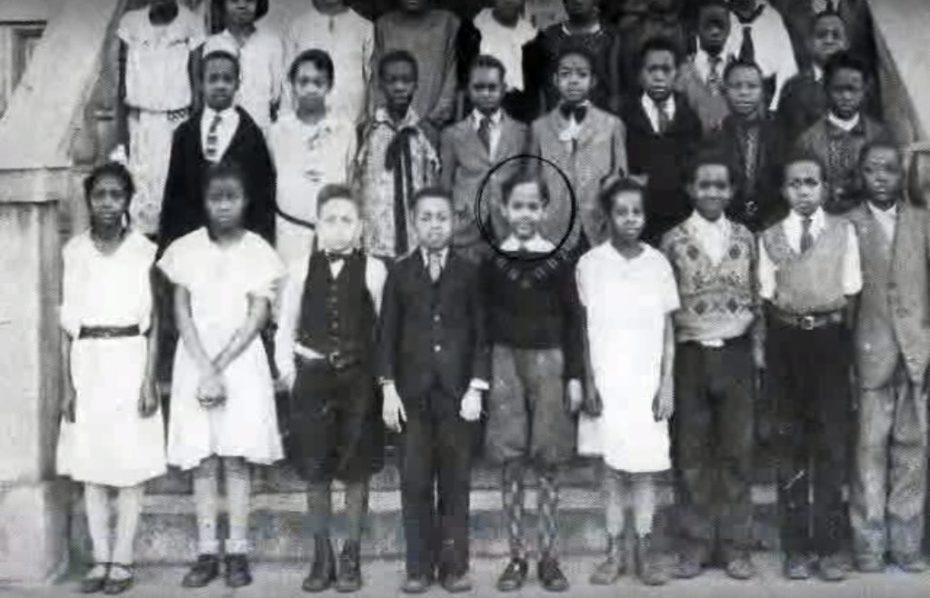

Two years after his death, LA Magazine reported an extensive piece on his true roots. It turned out that Pandit was an African American man, “John Roland Redd,” and grew up as the son of a baptist preacher in St. Louis, Missouri. When he moved to Los Angeles in the 1930s, he knew he’d have better luck in the music industry by passing as latino, so he crafted up a clever anagram: “Juan Rolando.”

“Rolando” was getting as many gigs in and out of the music and showbiz industry as possible. But it was the meeting his life’s love, Disney animator Beryl June DeBeeson, that led to Pandit’s creation. They met through his sister and her roommate at the time. The two had to marry in Mexico, as interracial marriage was still illegal,

There was a popular mid-century movie, explains Turner, that came out at the time, in which an African American man very clearly passes as an Indian man – and it almost certainly planted the seeds for Korla Pandit, whose story did have a few kernels of truth; like Redd, he was one of six kids. He was a prodigy on the piano. He believed in the healing power of music.

One of Korla Pandit’s first gigs was doing effects for a TV puppet show after meeting television pioneer Klaus Landsberg. It was Landsberg who helped him get his own show on KTLA, and it was Landsberg who decided Pandit’s high-pitched voice – and midwestern accent – perhaps wasn’t the best things to highlight.

After years of loyalty to Landsberg and KTLA, Pandit asked for a raise. He was making not nearly as much as his white contemporaries, but had three times the talent. When Landsberg refused, he walked, and found new work playing with another up-and-coming guy on the nightclub circuit: Liberace.

In some ways, Pandit made Liberace. The knack for eccentricities, the ability to gaze up from the piano and into the audience’s soul – these were all skills Pandit said he passed on. Unfortunately, the downsides of the showbiz industry – namely, the creative control it had over artists – soured Pandit’s career. He said syndication companies also held their talent on a tight leash, often refusing to pay them, prompting them to churn out hits . “I could see where things were headed then,” he said about stepping out of the limelight, “I refused to allow them to use me to rob people. I refused to do business with them so they hired Liberace instead.”

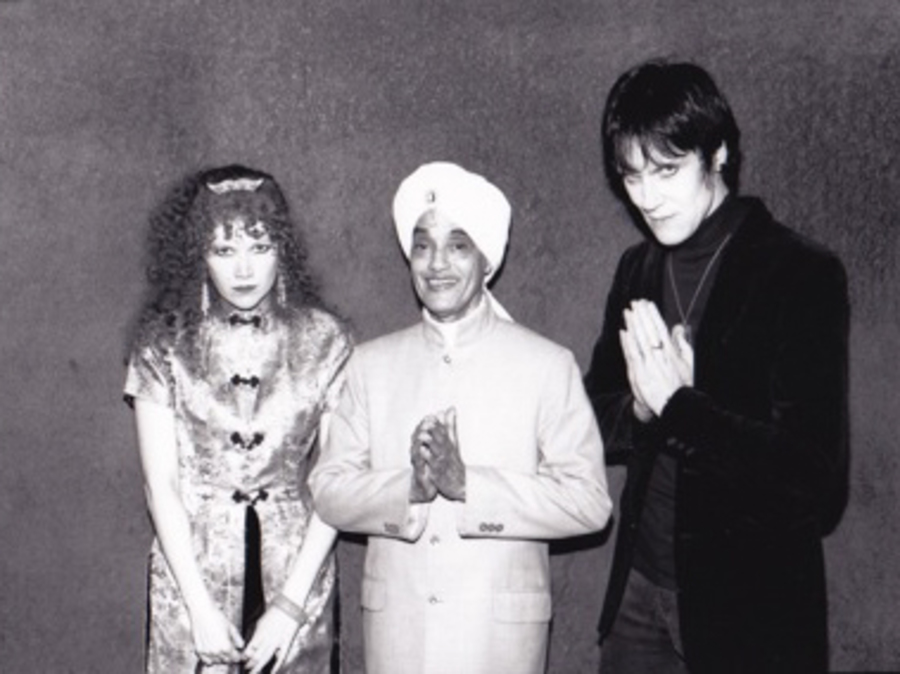

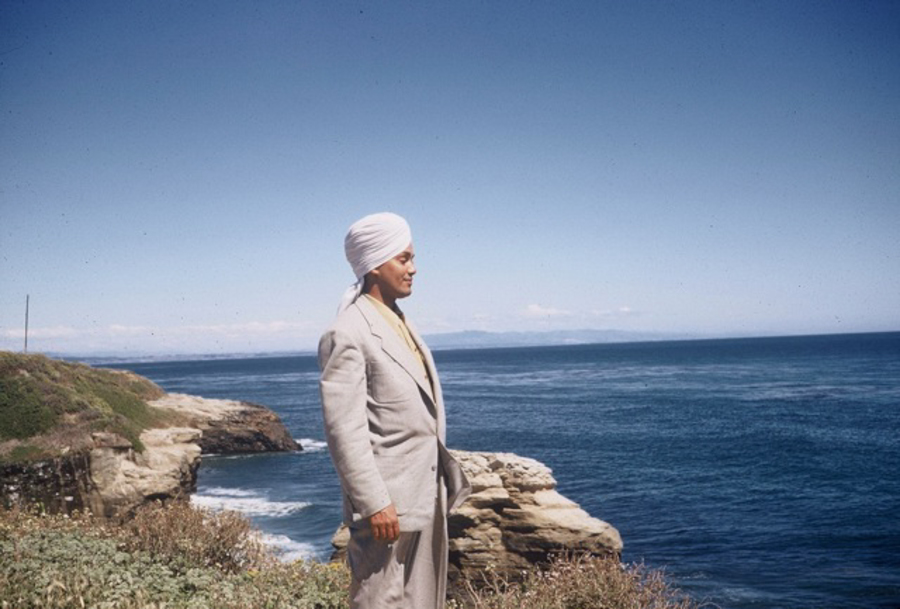

Pandit lived out his years in the Bay Area as a beloved local figure, and his last show at the legendary Bimbo’s 365 venue was a sold-out, standing ovation success. When the truth started to seep out after his death, those who hadn’t been familiar with his story all asked the same question: was the industry really so ignorant to his true identity? In all likelihood, no. But it was the kind of secret that was lucrative for everyone to keep, and in an industry that favourited reinvention, Pandit’s story was hardly unusual.

When Turner decided to go ahead with a documentary on his friend’s life, it was never with malicious intent. “We wanted to give Korla his props as the first African-American to have a television program,” he told NBC upon his documentary’s release. “He was talking about the universe of music being the universal language of love. He sincerely did believe in [its] being a tool to better the universe.” In that sense, Korla Pandit was the realest thing in the world.

Be sure to check out Turner and Eric Christensen’s 2015 documentary, Korla, available to stream on Fandor.