You know the daguerrotypes. Stiff scenes of Victorian families in too much clothing, expressing about as much enthusiasm for one another as one would have for a lamppost. That’s why we did a double – no, triple – take when we found a small selection of Victorian breastfeeding portraits in the depths of the web. How is it these women, for whom showing an ankle was rather scandalous, could suddenly feel comfortable exposing their bosom for the minute long exposure time needed for a daguerrotype? What was early motherhood really like for women in the Victorian era?

So. Many. Questions. Lest we should ever forget, women, especially mothers and wives, had little to no ownership of their bodies in the Victorian Era. The minute a woman married, she became “chattel, or property belonging to the husband”, and if they divorced (not likely), he automatically got the kids. In the UK, the 1839 Custody of Infants Act finally gave mothers access to their children if they were deemed of totally “unblemished character”. It also wasn’t until the 1884 Married Women’s Property Act that women were finally declared “an independent and separate person” by the court. Fun times.

Who were these breastfeeding snaps intended for? The moral bar of the era was set even higher for Victorian mothers, who had to embody chastity, patience, and a giving nature. The biological concept of motherhood was something you quite literally wore on your sleeve – the bigger the bustle, the better the child bearing hips.

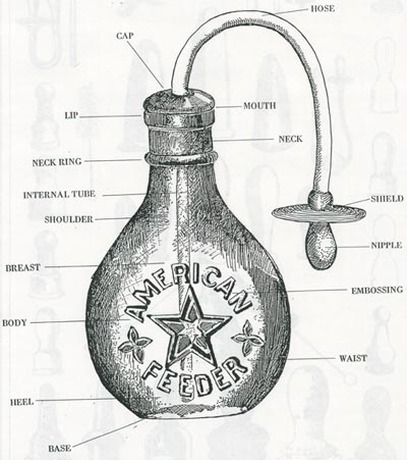

The act of breastfeeding was emblematic of a mother’s love, and for that reason the above daguerrotypes became intimate keepsakes. They weren’t put out on the mantle, but they were still prized as a testament to the notions of balanced motherhood and family in an era when bottled formula was on the rise, but rather controversial; Queen Victoria was a big fan of the bottle, writing, “I think much more of our being like a cow or a dog at such moments” about breastfeeding.

Still, other doctors warned against bottle feeding, saying that it caused Rickets by not providing adequate Vitamin D (up for debate), and bottles earned the nickname “Murder Bottles” due to the amount of bacteria they carried in their rubber, hard to clean tubes. Eventually, better knowledge of sanitation and food preservation led to more nutritious infant formula at the end of the 19th century, but even then, Catholocism favoured breastfeeding. In the manual In Mother and Child: Practical Hints on Nursing, the Management of Children, and the Treatment of the Breast (1868), author Charles Vine writes, “It was beneficently ordered by the Creator that the child for a certain period after birth should be dependent on the maternal nourishment for its support.” The pains of teething were often assuaged with a nipple shield to be applied over the breast either during or after feeding. Usually, they were made out of lead (and terribly toxic) or rubber.

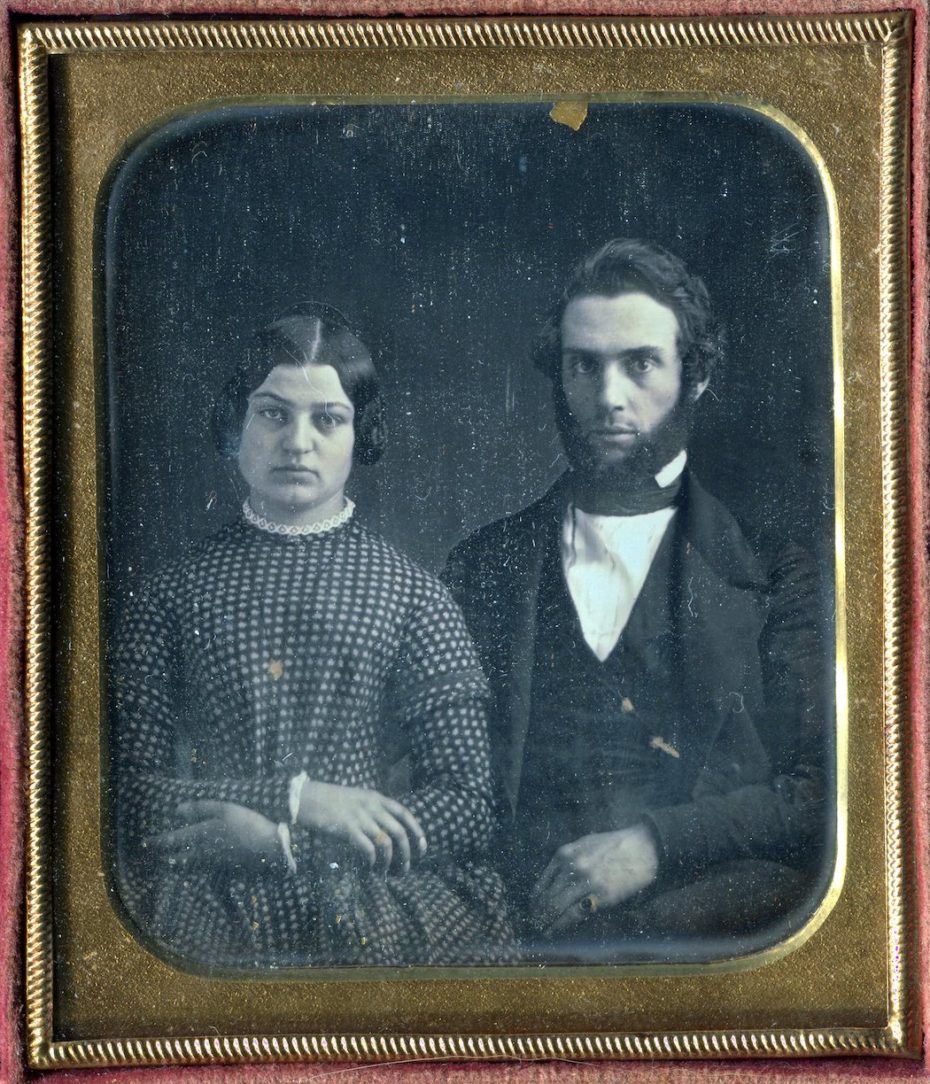

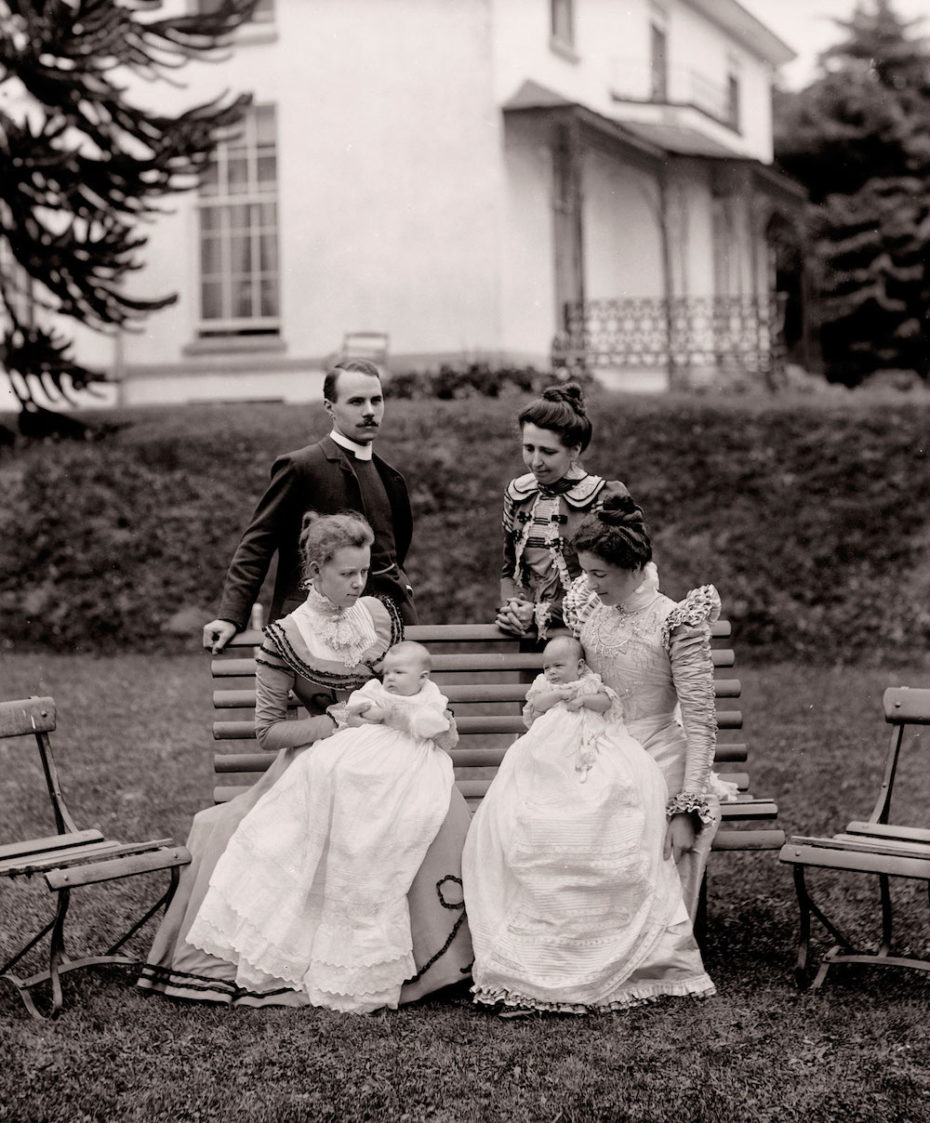

Typically, the middle to upper class used bottles or employed wet nurses, the latter of which even sat with the babies they tended to for portraits. Both wet nurses and nannies were extremely important fixtures of the well-to-do home, and spent more time than anyone with the baby.

Victorian mothers of a higher social standing were encouraged to see their baby but once a day. The widely read Cassell’s Household Guide encouraged an extremely cautious environment about what was said around the baby. As the purest of beings, a baby was intended to be sheltered from the happenings of the outside world and its adult scruples, quite literally kept our of earshot of adults in a sparsely decorated nursery.

That notion of restrained, and highly controlled visibility defined the Victorian Era. Christening gowns were long, not only to keep the baby warm during a baptism but to show off a family’s prominence.

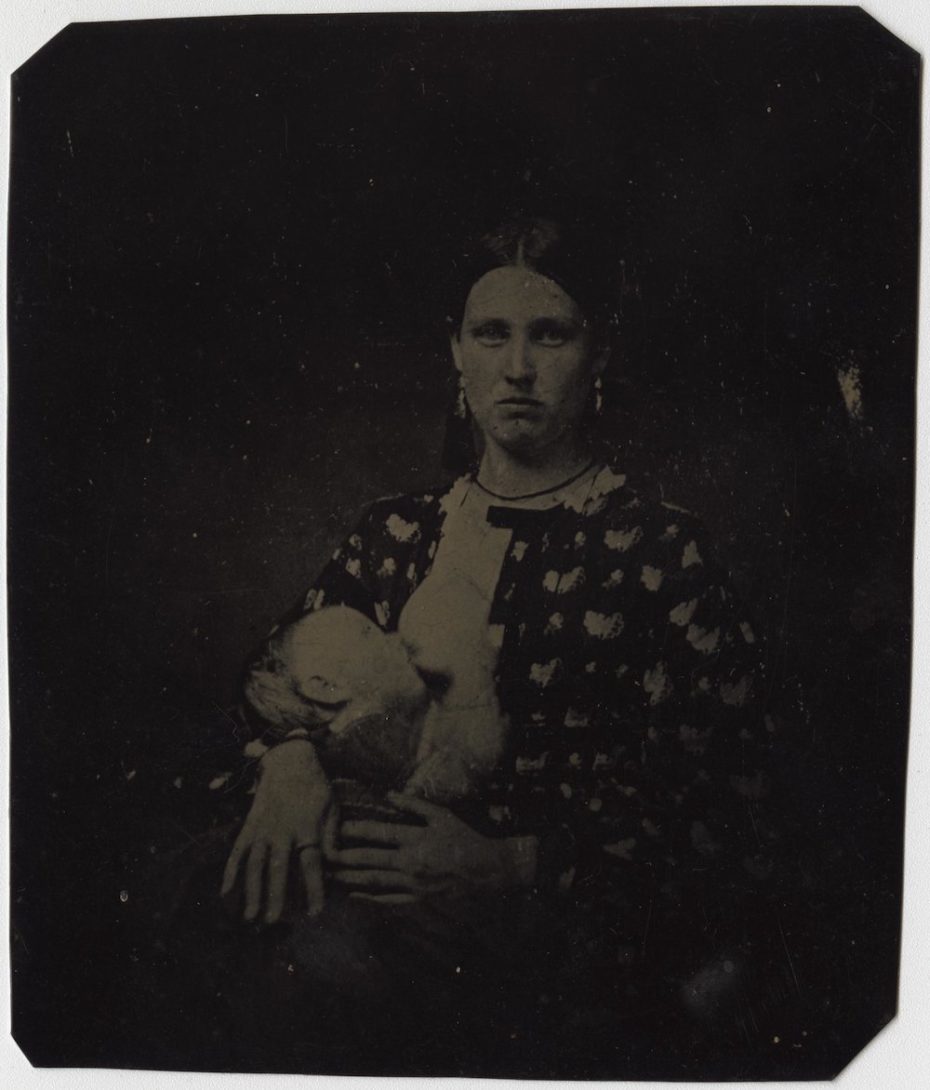

Baby portraits were often taken with mothers draping their bodies in fabric to pose as a faux armchair of sorts (the effect is rather eerie):

The actual birthing process often took place at home or in “lying-in” hospitals. One manual, Gunn’s New Domestic Physician (1861) wrote that “during labor [a woman] should always be well oiled or greased with lard, as it greatly assists and mitigates the suffering, and lubricates the parts of passage.” Childbirth was partially numbed through a sleeping draught known as “laudanum,” which was laced with opium, but other than that anaesthetics and hygiene weren’t top notch. Mortality rates were high for mother and child.

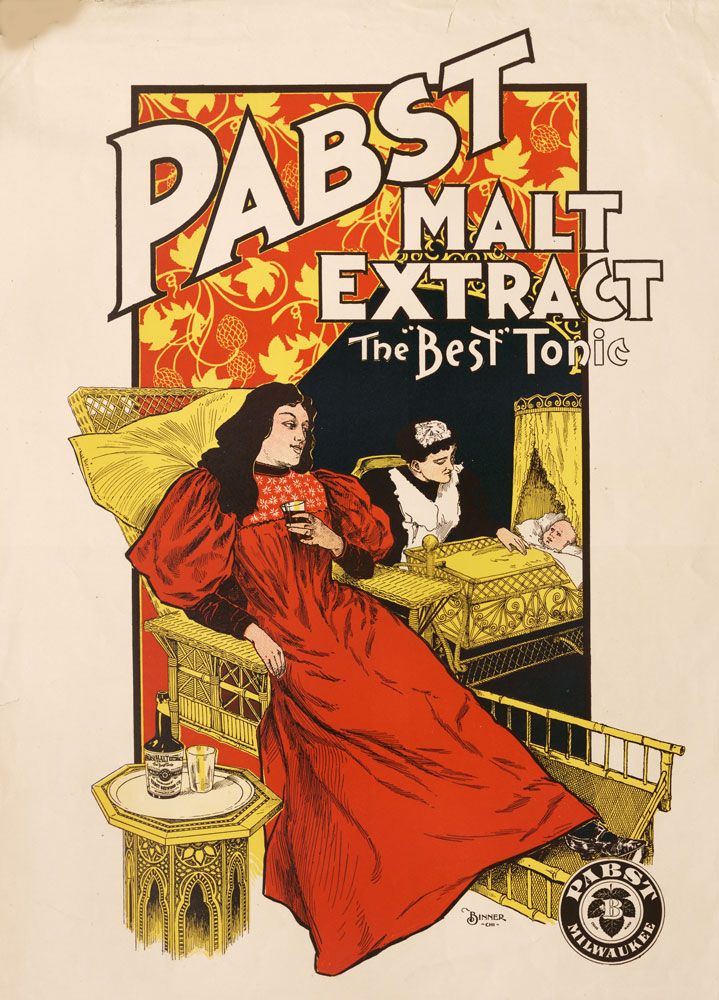

After giving birth, too much physical exertion was seen as dangerous for “the fairer sex” and a woman was meant to be kept in bed for nine days (whether she liked it or not). She wasn’t even allowed to eat much food other than fruit and gruel – but it was ok to have a bit of malt liquor or beer, the latter of which was considered to enhance the quality of breastmilk. Nährbier, which translates to “nutritional beer” was produced in Germany into the 20th century and targeted at young mothers.

Gradually, folks realised hitting the sauce wasn’t the best thing for mom’s breast milk. But they could prove to be rather sympathetic to women in postpartum depression. If you were a woman of a decent social standing, you’d be given the time and space to heal in a pastoral environment (i.e. the country estate) to get ready for the next stages of motherhood.

With the development of better infant infant formula – and the squeeky clean, type-A 1950s nuclear family – breastfeeding gradually became stigmatised, particularly in public. In fact, up until the 1990s, governments slacked on providing public breastfeeding spaces, and it wasn’t until 1999 that women in the States were allowed to breast feed on Federal property. Overall, the Victorian Era is painted as an oppressive time for women (and very rightly so on many fronts). But it’s important to keep digging out the kernels of progress from the period, to keep our own in check.