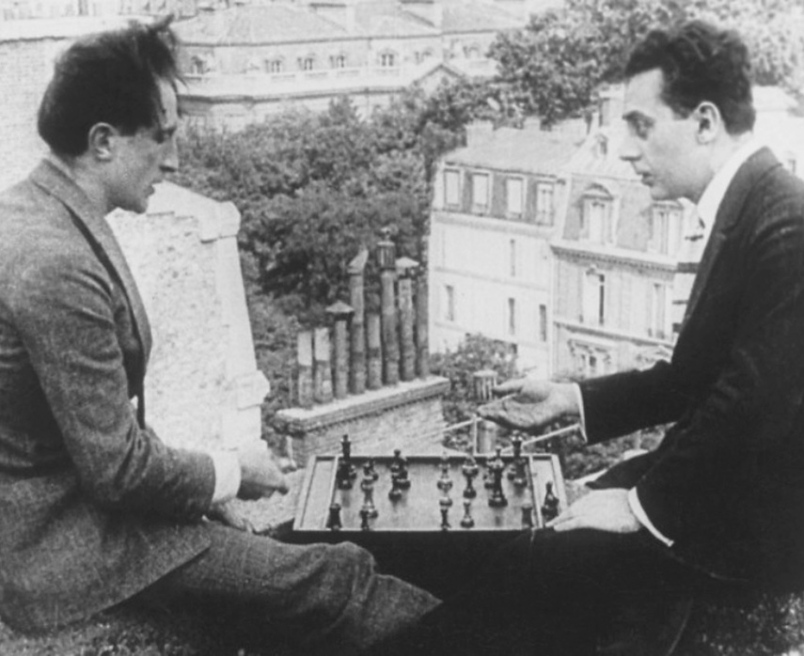

It’s a question we asked ourselves recently in a Messy Nessy editorial meeting after finding yet another photograph of the 20th century artist playing chess in some unusual, avant-garde manner. Discovering a person’s hobby can be so deliciously voyeuristic. It’s a window into the way they switch-off from the world, and one made all the more intriguing by a person who seems, well, inseparable from their vocation. Sylvia Plath loved beekeeping, Da Vinci played the lyre and Marcel Duchamp? Well, it turns out he played chess. In fact he was so obsessed with playing chess, that after he stayed up all night during his honeymoon studying the game, his wife glued the pieces to his chessboard. They were divorced three months later. The game never ceased to enchant his brain and ultimately the Dadaist leader quit the art world and devoted the rest of his life to playing the game of life.

“I am still a victim of chess. It has all the beauty of art – and much more. It cannot be commercialized. Chess is much purer than art in its social position.”

Marcel Duchamp

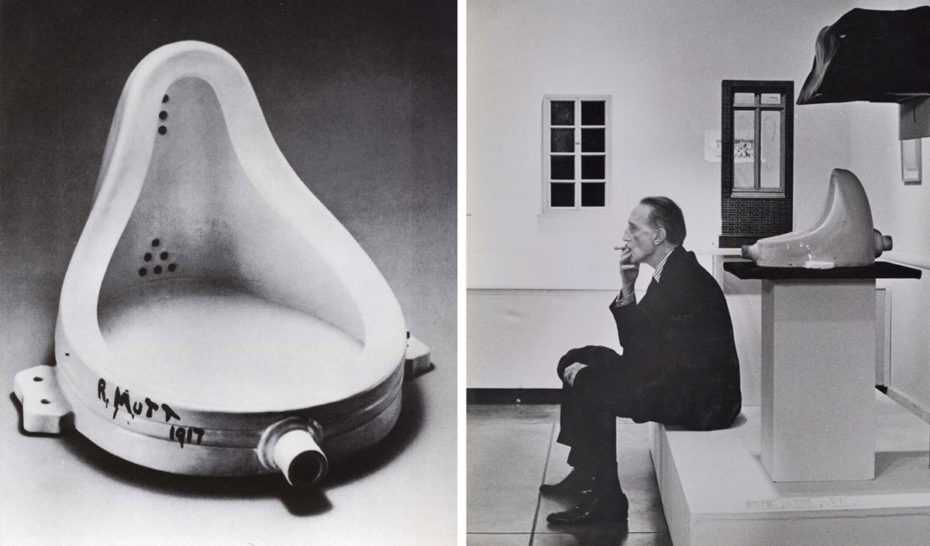

One of the most famous and controversial artists of all time, you know Duchamp, and Dada, even if you don’t think you do. That iconic urinal sculpture that became one of the most influential artworks of the twentieth century? That’s Duchamp (at least partially). At its core, Dadaism lived in a sense of disillusionment, and dark humour. Works reflected the absurdity of the violence left in the wake of WWI, which Duchamp escaped from and made New York City his new home. The artist’s “Readymade” works, which were usually assemblage pieces fashioned from everyday objects (i.e. your toilet), challenged the old, conservative, academy-based art world.

In the midst of a world that wasn’t making sense, there was chess. For Duchamp, unfolding a board and strategising offered a logically gratifying – and stimulating – conversation. “The [only] problem,” as he later said, “is that chess is a school of silence.” So he turned that silence into a gift. After all, peace and quiet was a luxury in New York City, and chess was selling it cheaply. “

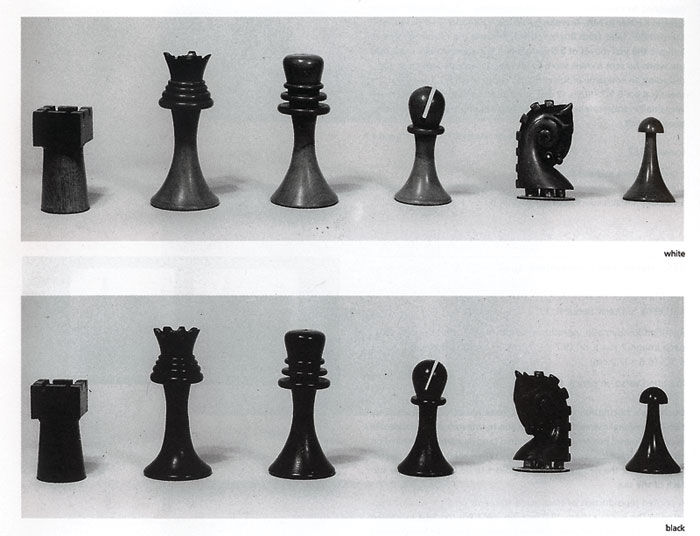

The Chess pieces are the block alphabet which shapes thoughts,” he said, “and these thoughts, although making a visual design on the chessboard, express their beauty abstractly, like a poem.” The game soon became a regular motif of his work.

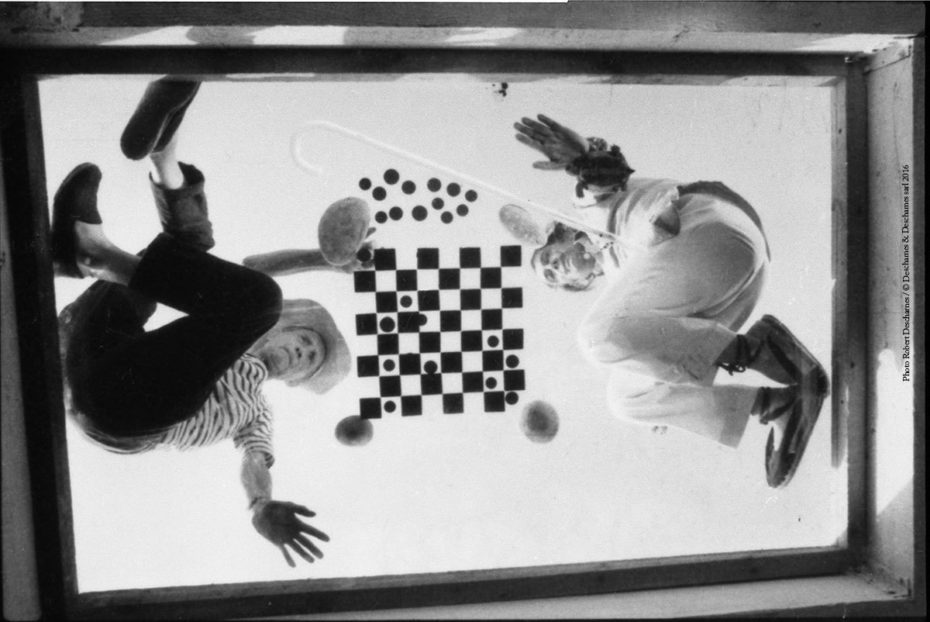

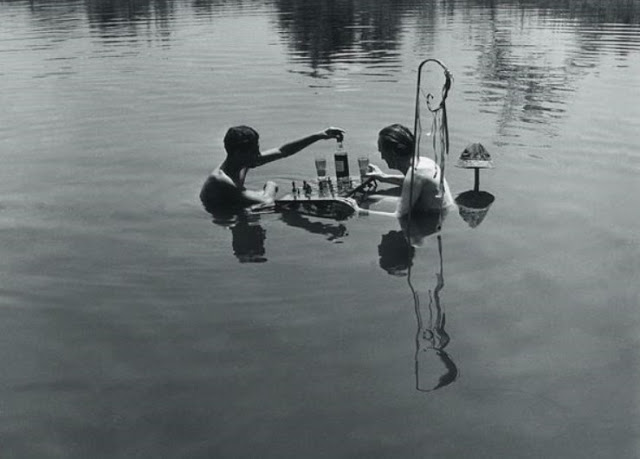

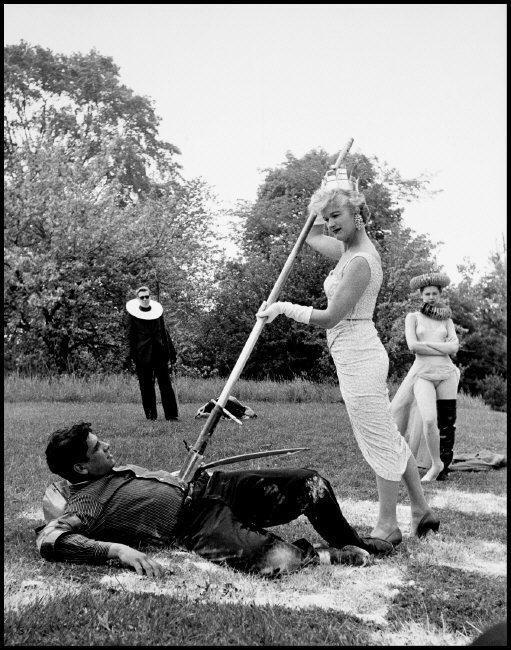

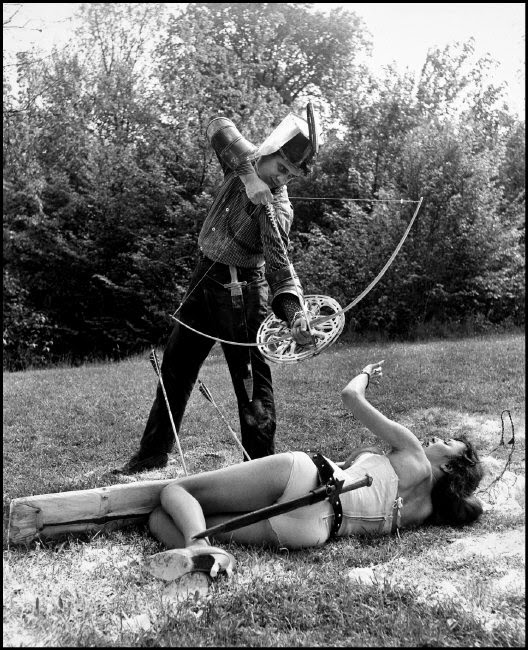

He designed his own set, as well as a large, mock-board that was put up on the wall in his studio. He played life-sized games on Connecticut lawns, or while swimming in lakes.

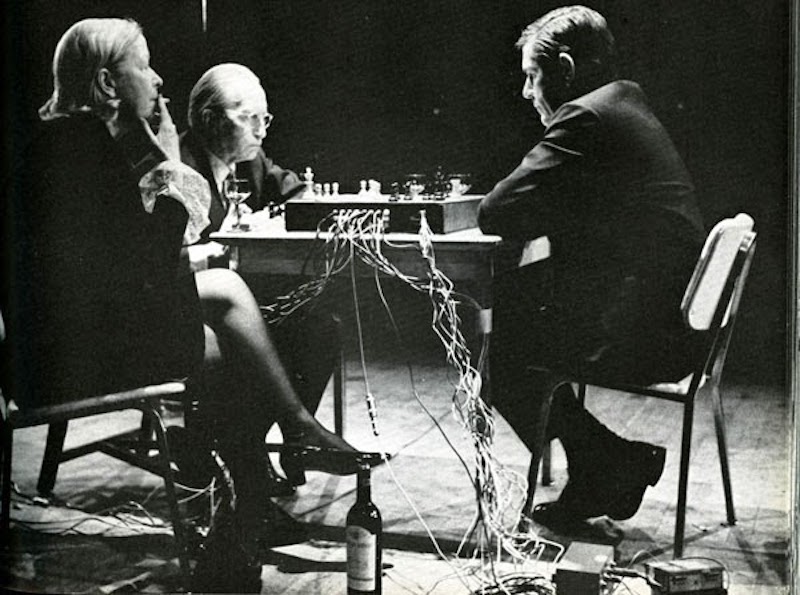

He was eager to play in any circumstance he could, which is precisely how composer John Cage used it as a premise to get to know him better. Cage was a composer and a leading figure of the post-war avant-garde in America. Like Duchamp, he savoured silence, and put out his most famous track in 1952, 4′33″ – as in, four minutes, and thirty-three seconds of complete and utter silence. Naturally, Duchamp was intrigued when he asked to learn chess under the master, and the two played a public game that doubled as performance art (called, “Reunion”) in 1968. It was no contest, and Duchamp won in a matter of minutes (Cage went up against his wife instead. And also lost).

Still, the board’s squares provided a fun electronic and visual experience, as each move activated a sound and image that was projected to the audience.

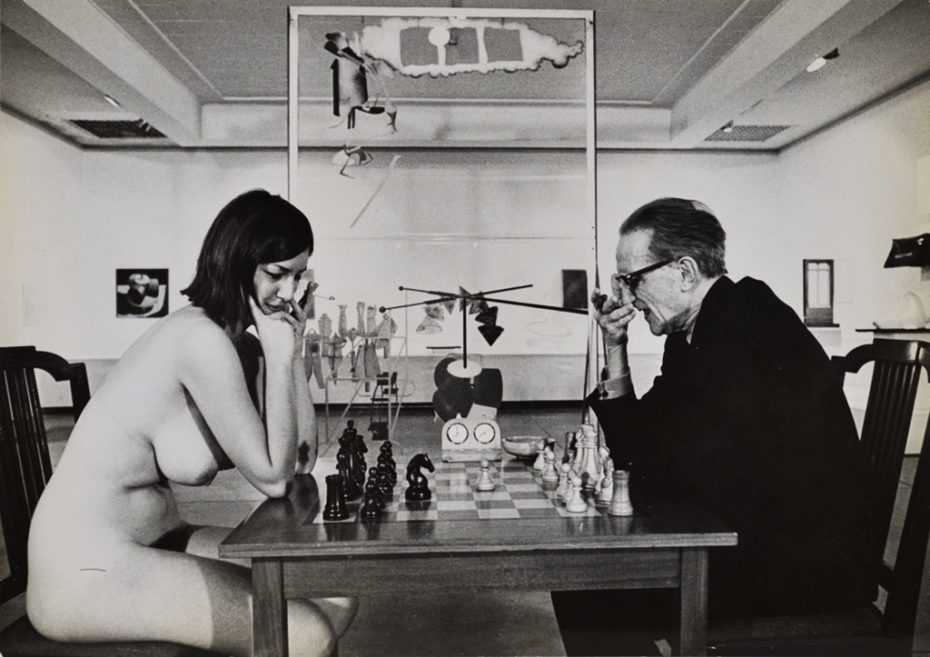

In the 1960s, he went up against the renowned writer Eve Babitz while the latter was totally naked. A student climbing the ranks in the creative world at the time, Babitz proposed the idea to Duchamp in order to get back at her lover, the legendary gallerist Walter Hopps. Mr. Hopps was a married man when they were together, and consequentially didn’t invite her to the opening night of Duchamp’s show at his gallery as the missus would be there. So Duchamp and Babitz found a clever way to give him the middle finger…

Almost religiously, he’d head to chess nights at the apartment of art patrons Louise and Walter Conrad Arensberg – but when chess developed more and more into a “scene” amongst the Dada set, he travelled as far as South America to plunge himself into study of the game with a renowned tutor.

The game gave his brain an ice bath from the piping hot energy of the Manhattan art scene. Chess players, he said “are madmen of a certain quality, the way the artist is supposed to be, and isn’t, in general.” Duchamp always had an element of chill that most Dadaists didn’t, and at many moments his love of chess surpassed even his desire to make art.

“Nothing in the world interests me more than finding the right move,” he wrote to friends in 1919, “I like painting less and less.” In 1923, he officially declared his art career over (eventually, he’d resurface with new works).

“While all artists are not chess players,” Duchamp once said, “all chess players are artists.” And when an artist for whom the very task of living is considered, well, an art, a simple hobby became a profound extension of his genius. Or at least, one hell of a check-mate.