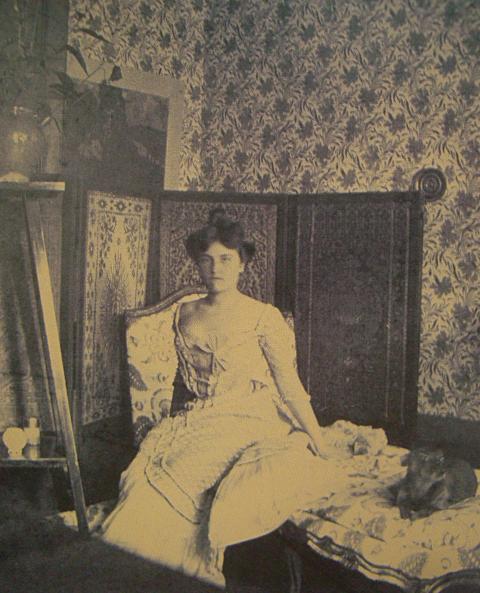

Proust, turned her into a fictional princess and Ravel turned her into music. Renoir and Toulouse-Lautrec couldn’t stop painting her. Picasso was a confidante, Serge Diaghilev of the Ballets Russes, a best friend, and Coco Chanel – her “soul sister”; possibly her lover too. Belle Epoque Paris bloomed with opulence and a languid, if not tangled sensuality – and she was at the heart of its germination. If life, love, and divorce gave her many last names, it’s because Belle Epoque pianist, muse, and overall “It Girl”, Misia, was a collectioneuse of creative credits over a rather tragic life. Today, we’d like to introduce a fashion icon’s closest ally, an artists’ greatest muse, a mysterious woman lucky only in jilted love who inspired everyone around her, and yet history seems to have forgotten her name. Let’s meet Misia…

We have a bit of juicy ground (and quite a few husbands) to cover before we get to Chanel – so let’s take it from the top.

Misia was born Maria Zofia Olga Zenajda Godebska in 1872, just outside of St. Petersburg, Russia, to a prominent sculptor to the Czar (her mother passed away in childbirth) who didn’t have much interest in raising her. So Misia was shipped off to Belgium to live with grandma and grandpa. She grew up playing piano on the knee of family friend Franz Liszt, and was sent to boarding school in Paris.

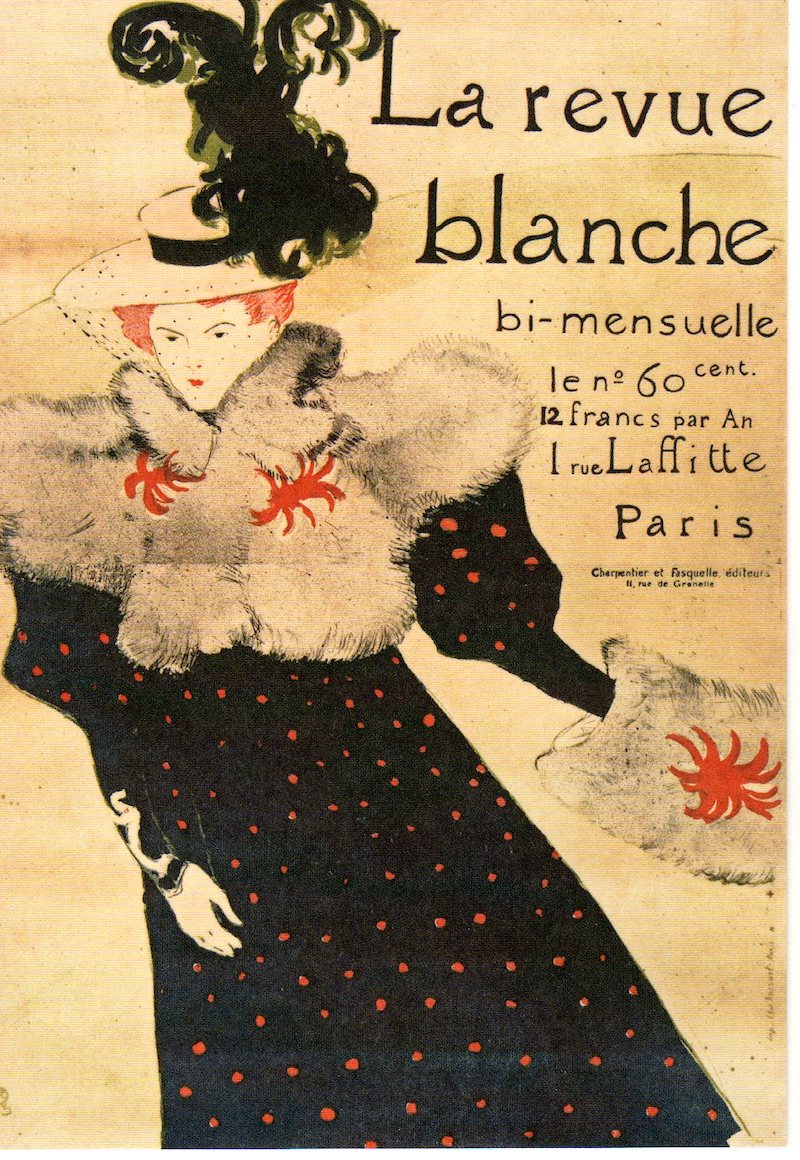

Misia always said she “took only husbands, never lovers,” and the first of her three tumultuous marriages was to her Polish cousin Thadée Natanson, an Editor of La Revue Blanche. The Natansons’ home at the Rue St. Florentine became the happening spot for everyone who was anyone to mingle: Debussy, Mallarmé, Signac, Proust, Gide, and Renoir were regulars at their cocktail parties, and Toulouse-Lautrec was usually behind the bar mixing up his deliciously lethal Pousse-Café (a rainbow cocktail of colourful, layered liquors we’ve yet to try).

It was an ever-evolving cast of characters, but the heart and soul was Misia. To say she was the hostess with the most-ess is a gross understatement; an invite to dine at her house was more coveted than a spot in some of the most renowned Parisian salons. You didn’t just gain high-ranking company with Misia (though that was part of it). You gained a front-row seat to her self-proclaimed, “sexual stir of worldly ambition,” the opportunity to absorb a bit of her ineffable charisma into your next artwork…

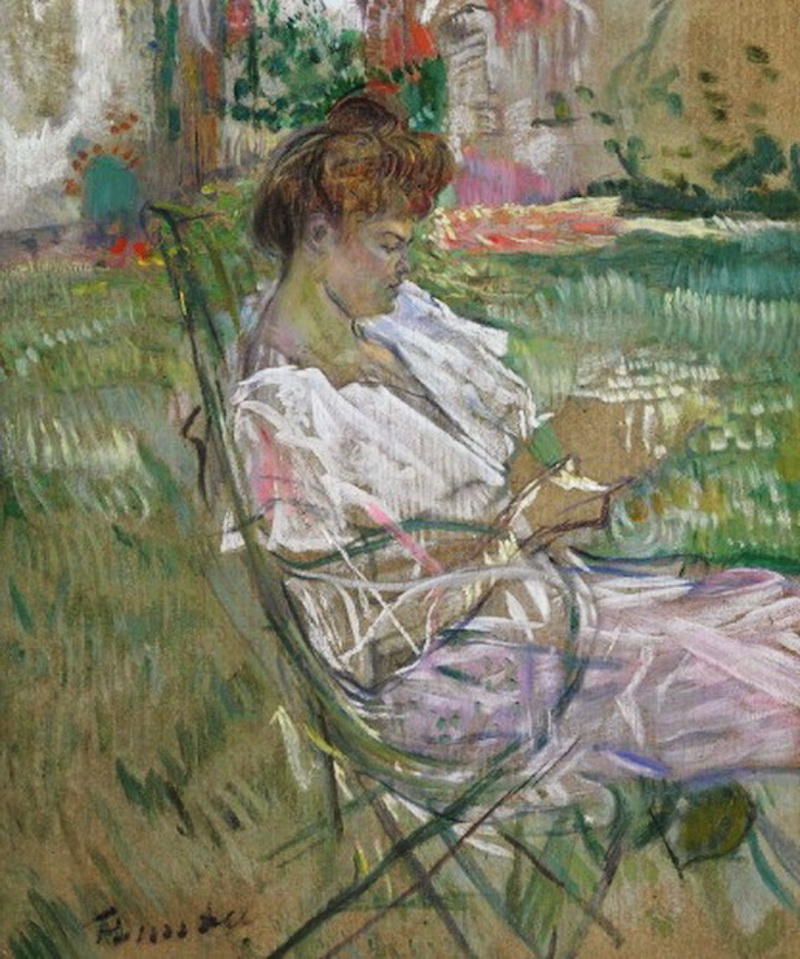

She had numerous admirers, particularly those who ended up collaborating with her husband’s magazine, the Revue Blanche (even a fledgling Picasso got involved). So did the painter Edouard Vuillard, who fell hopelessly in (unrequited) love with Misia. For the rest of his life, Vuillard’s paintings captured his fascination with her through works both tender and intimate. His brushstrokes immortalised her warmth by blanketing her in softness, a golden light, and almost always at her beloved piano.

If there’s one thing we can take away from her character through his works, it’s that Misia was a natural giver – a trait that would become key to her dynamic with Chanel, who understood the power of that trait.

In fact, in the words of her Chanel, “Woman has everything, but Misia has every woman.” Composer Maurice Ravel dedicated La Valse (The Waltz) to her, a song that still sends the spirit twirling into unabashed giddiness. You likely know Ravel, even if you don’t think you do: the emotive score of Luca Guadagnino’s film Call Me By Your Name (2017) is almost all Ravel. No wonder his songs lent themselves so well to a sun drunk love story.

What we wouldn’t give to go back in time for one of those lazy, late afternoon lunches that spills unabashedly into the evening at the Natansons’ apartment in Paris, or at one of their country houses.

Just as the Natansons were solidifying their place as the reigning hosts of Belle Epoque Paris, trouble came knocking. The bi-annual periodical La Revue Blanche wasn’t cheap to produce, and Natanson was desperate for a backer. He found one in newspaper magnate Alfred Edwards, founder of the esteemed Le Matin paper, who was already having an affair with Misia. Edwards demanded that Natanson divorce Misia, or he’d walk on his investment. Thus, in the winter of 1905, Misia became Mrs. Edwards.

It’s hard to say how Misia felt about Edwards in her heart of hearts, but obligation certainly doesn’t set the tone for true romance. Still, after a while she wrote that she began to feel “the agitation which strongly resembles love”, and continued holding court at her new, glamorous apartment on the Rue de Rivoli in Paris overlooking the Louvre’s Jardin de Tuileries. If you want our two cents? We think Misia fell even more in love with her social circle, not Edwards. But even that wasn’t enough for her to endure the her husband’s constant cheating – and when fellow It-Girl Geneviève Lantelme came into the picture, things really got ugly.

Lantelme was a powerhouse. As a rising stage actress, she drew comparisons to the great American actress Ethel Barrymore (As in, Great Aunt of Drew Barrymore), aka “The First Lady of the American Theatre.” She also came from a very impoverished past, and knew when to whip out her claws for something she felt she deserved. In this case, that something was Edwards.

But Misia was also a survivor, and a woman who had made her fame not just as a trendsetter, but a cultural chameleon; when the Nabis painted her bright hats, she bought even brighter ones. When Lantelme dolloped her hair ‘just so’, Misia attempted the same. “I had contrived to get a photograph of Lantelme,” she wrote in her diary, “it adorned my dressing-table, and I made desperate efforts to look like her, dress my hair in the same way, wear the same clothes.”

Even Proust used the mounting jealousy between the two as inspiration for his characters in In Search of Lost Time. It was a low period for Misia, who had found herself battling for the dignity of a marriage she never wanted in the first place. Edwards divorced her and remarried Lantelme, but in an eerie twist of fate, the latter fell to her death from his yacht in 1911.

Just as things were looking rather grim for her love life, Misia met José María Sert, a confident Catalan painter who she declared the one true love of her life. Today, you can see some of his dramatic work on display at Paris’ Carnavalet Museum (re-opening in 2019).

Through Sert, she also formed lifelong friendships with the composer Igor Stravinsky and the founder of the Ballets Russes, Serge Diaghilev, both of which she practically saved from financial ruin during the Russian Revolution. That’s perhaps the most marked thing about Misia’s union with her third husband Sert: it solidified her transition from a hostess of the arts, to a true saviour of the arts as its discerning mother hen.

But heartbreak came knocking once again at Misia’s door in the form of her husband’s newfound love for the Russian princess Isabelle Roussadana “Roussy” Mdivani. The young Roussy was a part of a clan called the “Marrying Mdivanis”, due to their habit of marrying into affluent families. One day, Roussy came knocking on José’s studio door for advice on her own work. “When, after three or four days, I realized that the visits were continuing, I decided to meet this young Princess of whom Sert spoke with such excitement,” wrote Misia, “I realized at once what it was that had captivated [José]. He was right in all that he had said about her. She was exactly as he saw her. She was ravishing”. Something broke in Misia when José met Roussy. For a while, the three tried to live together in a bohemian-inspired ménage à trois at the Hôtel Meurice, but they eventually divorced in 1927. On her own yet again with her heart on the mend, she met Chanel.

Their meet-cute was at a dinner party in 1917, when Misia complimented the up-and-coming designer’s coat. Chanel knew who she was rubbing shoulders with, but Misia knew only that she’d met a woman who was a breath of fresh air in her world. She saw a lady with class, and acerbic bite. Misia said she loved “[her] genius, lethal wit, sarcasm and maniacal destructiveness, which intrigued and appalled everyone.” Above all, she loved her loyalty. Both Misia and Chanel had dealt with their fair share of fleeting men – if anything, they bonded over a shared sense of endurance.

But Misia and Chanel weren’t so much peas in a pod, as they were pieces of a complex puzzle: one fulfilled the other. They met just two years before the untimely death of Chanel’s her lover and muse, Arthur Capel, in a car crash. That pain was numbed through the magnetic, ever giving friendship Chanel found in Misia – that, and the pair’s fondness for morphine — one of the more tragic elements of the relationship (and one visible in Misia’s whittled down frame later in life).

Misia always had the ability to inspire, embody, and then amplify the sensibility of the art she inspired. But nowhere was that talent more present than in her relationship with Chanel, who bedecked Misia in her own empowering designs. There’s something rather serendipitous about Misia – a woman so jilted by men – meeting Chanel, who played a huge role in dressing the autonomous, modern woman. These days, there’s even a Chanel perfume named after her:

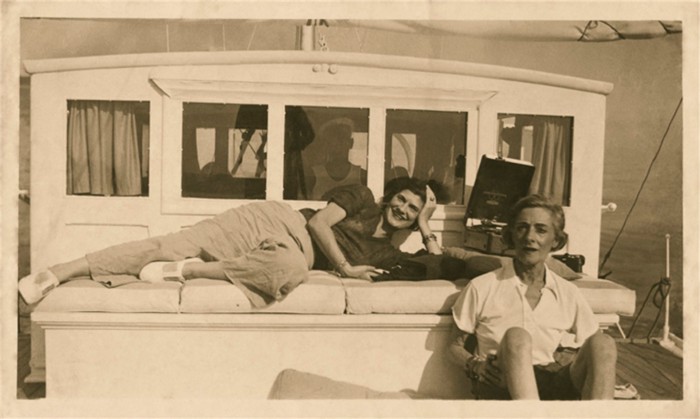

In fact, it could be argued that it was Misia who “discovered” Chanel; if it weren’t for Misia, the road away from being a mere seamstress would have been longer. “Without the Serts,” Chanel later said, “I would have been an imbecile”. The women were inseparable, often escaping to Venice to romp in the sun and forget their troubles. Word about town was that they were lovers. The two ladies diplomatically declared themselves, “soul sisters.”

When Misia passed away in 1950, it was Chanel who made the arrangements for her funeral, who stood guard over the procession, like a watchdog, to decree who could and couldn’t pay their respects. It was Chanel who literally dressed her for death in her own designs, and her own affection. The story of Misia’s life is inextricably bound to, and enriched by the people she loved. But rather than define her by the husbands she lost, let’s celebrate her union with the arts and look out for clues to her legacy. Once you know her face, you’ll find that Misia is in fact everywhere – hanging on the walls of the most prestigious museums around the world. And when you find her – it’s likely that no one else in the gallery will know her name, her story and the life she lived, but you will.