They’re performers. Dandies. Men with a streak of the mad poet. Writers, dancers, and professional party boys. Though these eccentrics span across generations, all share a brazen commitment to being themselves that’s made for some of the most memorable menswear moments in the 19th and 20th centuries. Long before fashion was giving the middle finger to the gender binary, these men were swapping suits for sequins, and wrapping themselves up in what looked like an Aladdin’s cave of Persian rugs. From the heels of revolutionary France, to the intergalactic landscape of Afrofuturism, we present the sartorial stories of our top five painted peacocks…

Henry Cyril Paget, the Fabulously Reckless Socialite

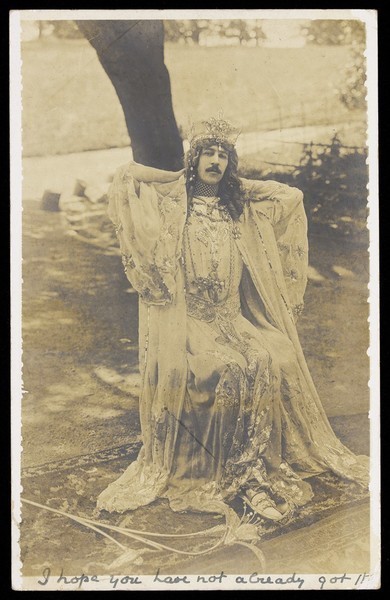

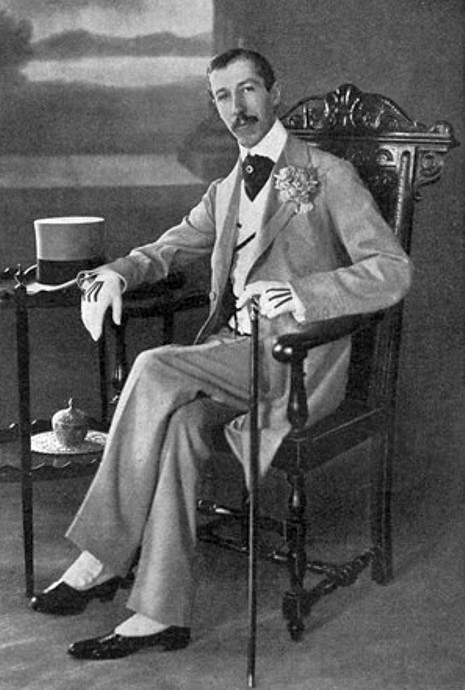

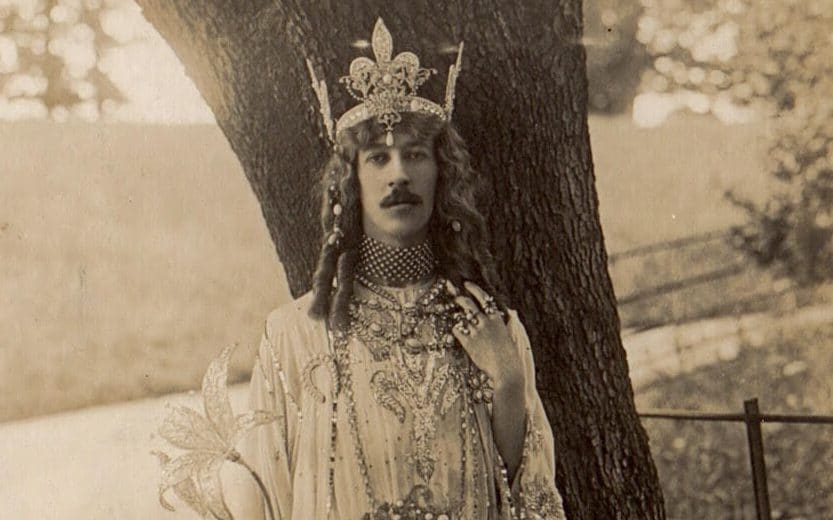

Once upon a time, there was a young British man who owned 30 pairs of fine silk pyjamas, 100 dressing gowns, and a car with perfume-filled exhaust pipes. His name was Henry Cyril “Toppy” Paget, the 5th Marquess of Anglesey. In 1898, Paget inherited a whopping $70 million dollars from his family’s mining business – and with that money, he found unbridled freedom to literally outfit his dream life…

He renamed the family estate of Plas Newydd (in Wales), “Anglesey Castle”, and transformed it into a theatrical wonderland. The chapel became a 150 seat venue called “Gaiety Theatre” (complete with electric stage lighting), and Paget used his money to entice the best actors to perform with him in productions. No matter what was on the program for the evening, they always had to leave room for him to perform his signature “Butterfly Dance”. Was it vain? Probably. Fabulous? Undoubtedly. That’s what made him so hard to deal with in the upper echelons of society.

Paget was still married when he inherited his fortune, but eventually divorced his wife. They claimed the marriage was never consummated, and his wife said the closest they got to physical intimacy was his asking her to pose in nothing but diamond necklaces. Once the divorce was finalised, Paget really upped the ante on his dandyism, buying his weight in furs, pearls, and pimping out his charabanc (an early horse-drawn car). With his towering, slender physique covered in precious fabrics and gems, Paget looked rather like the kind of mythical, ancient figure you’d find in the corners of a medieval tapestry.

The rest of the story is a classic, tragic tale of how Paget burned a hole in his silk-lined pockets. When he died at 29 years old in Monte Carlo, it was with debts of almost $75 million, and his possessions – namely, his clothes – were so vast they took 40 days to sell at auction.

Generally, there are two ways history looks at Paget’s legacy. One is from the perspective of the stick-in-the-mud family members heartbroken not only from his reckless spending, but from his gender non-conforming identity. Plus, they said he was a huge narcissist. Which, to be fair, was probably true. How else does one justify owning 260 pairs of white gloves?

The other, more recent retelling of his legacy is that of a charismatic (but foolish) man who had the courage to celebrate his individuality. Rather than conform, he broke out spontaneously into “sinuous, sexy, snake-like dances” in his bedazzled baroque heels. These days, the locals of his old township refer to him lovingly as “Lord Gaga”. In a time and place where coming out was a crime, Paget wore his gender identity on his sleeve with feminine and androgynous gowns.

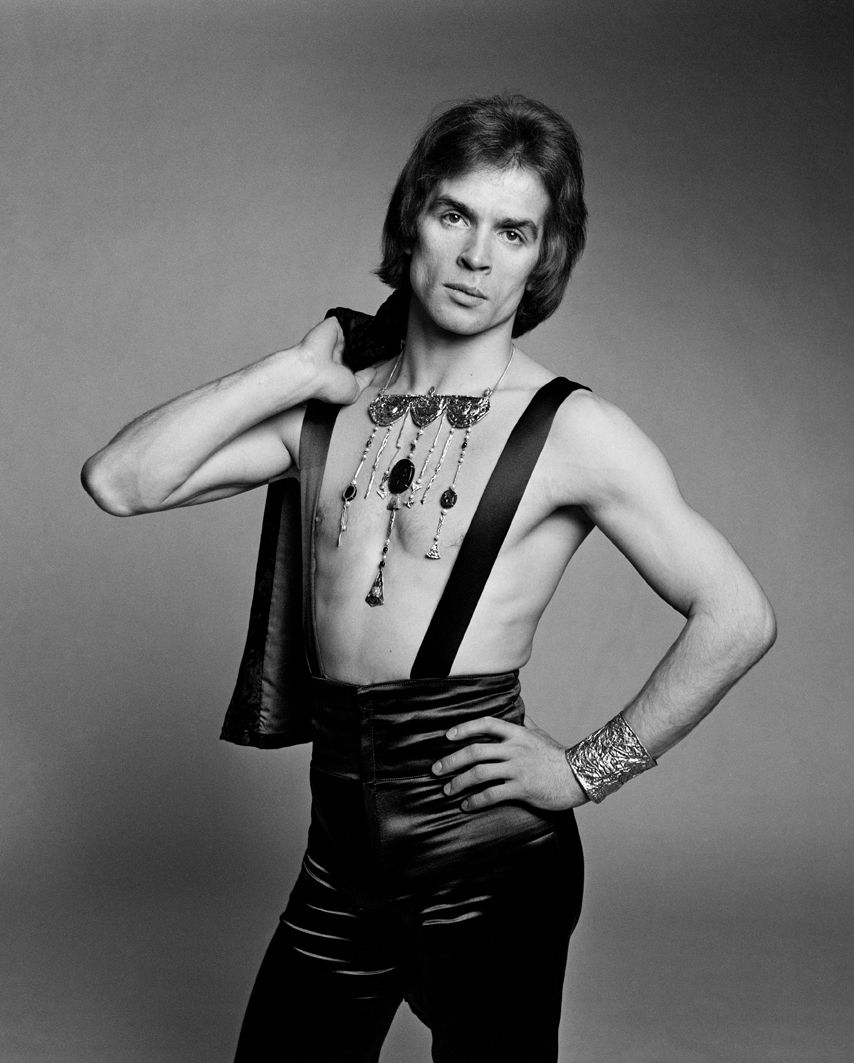

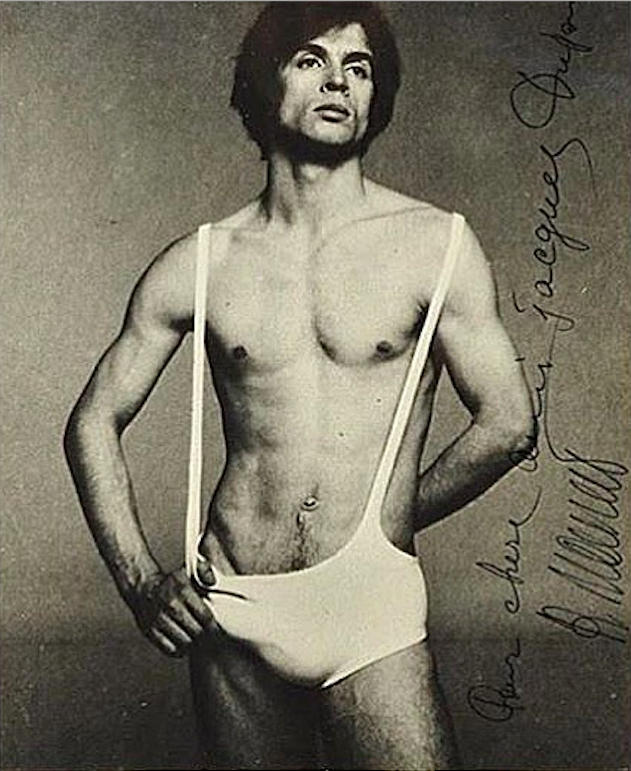

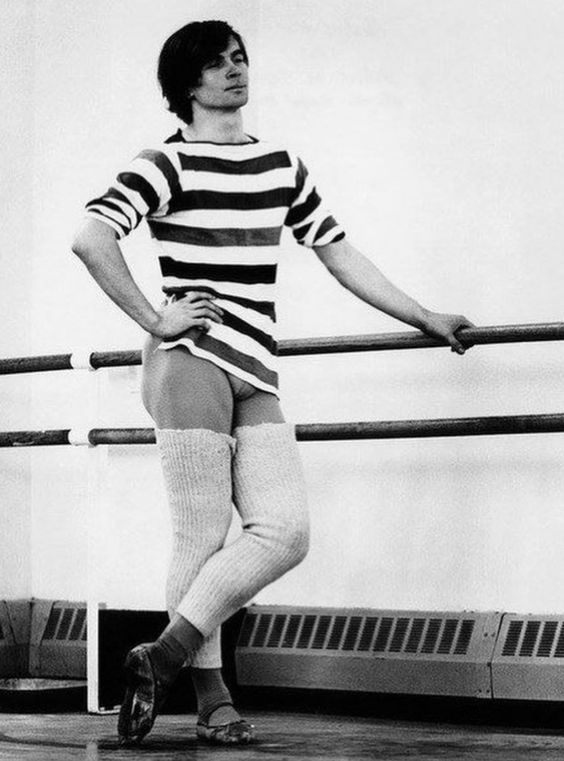

Rudolf Nureyev, the Mick Jagger of Ballet

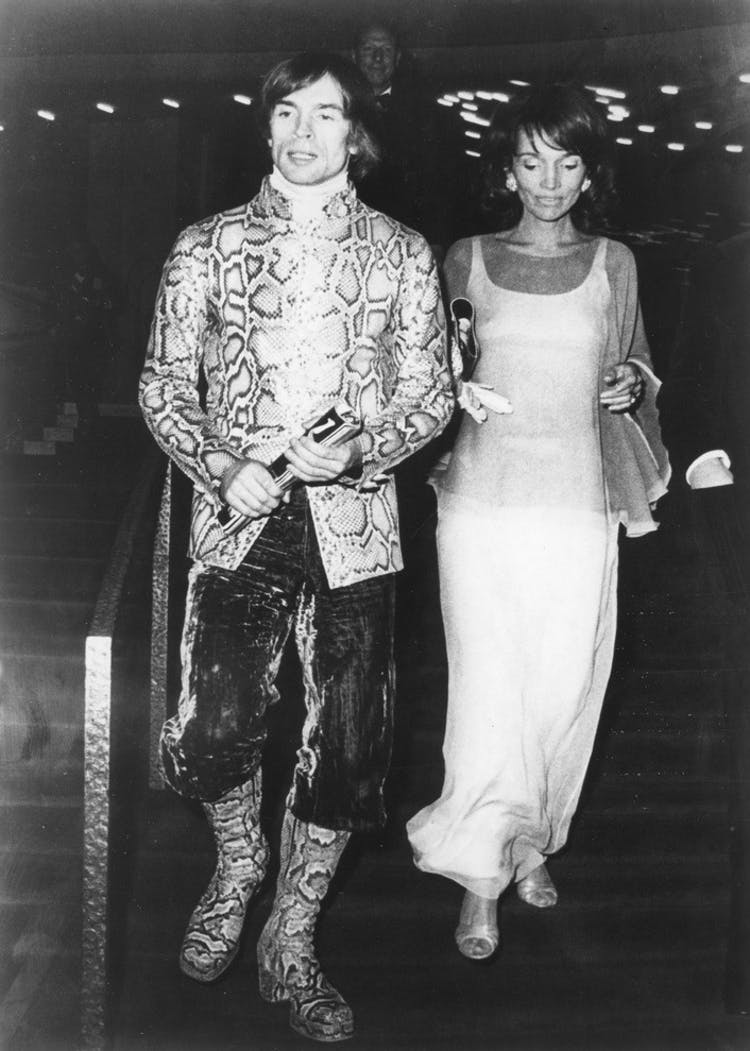

Rudolf Nureyev was born in motion. In 1938, inside the rickety cabin of a Trans-Siberian train, the dancer came into the world and hardly ever lost momentum. Artistically, he’s hailed by many as one of the greatest ballet dancers and choreographers of his generation. Sartorially, he effortlessly blurred the lines between costume, casual wear, and rehearsal wear. Not to mention this look (complete with Jackie O’s hip sister, Lee, as arm candy):

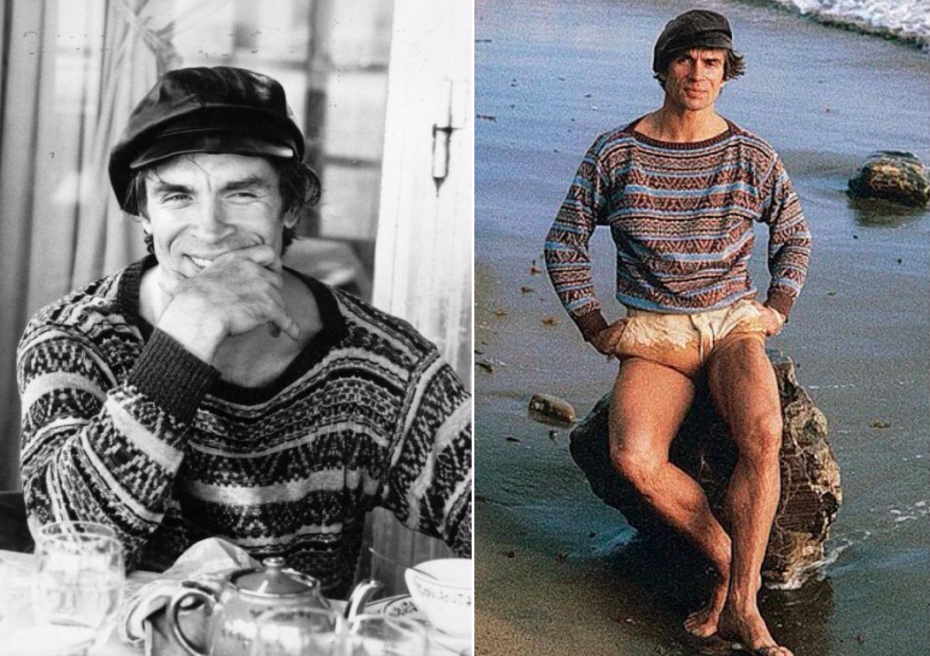

Nureyev was the definition of work hard, play hard. He danced with the Royal Ballet in London, and served as Director of the Paris Opera Ballet. Under his stewardship, already long company tours were made longer (and then extended). “He showed dancers how to jump an extra measure higher and not to be afraid of the grand manner,” wrote one New York Times critic in 1993, the year of his death. “The public flocked to see him and he was often compared with rock stars.” He had the style, the diva demeanour, the cheekbones that could cut a steak in half. As one Sunday Times dance critic famously declared in 1962, “A pop dancer – that’s what we’ve got – a pop dancer, at last.”

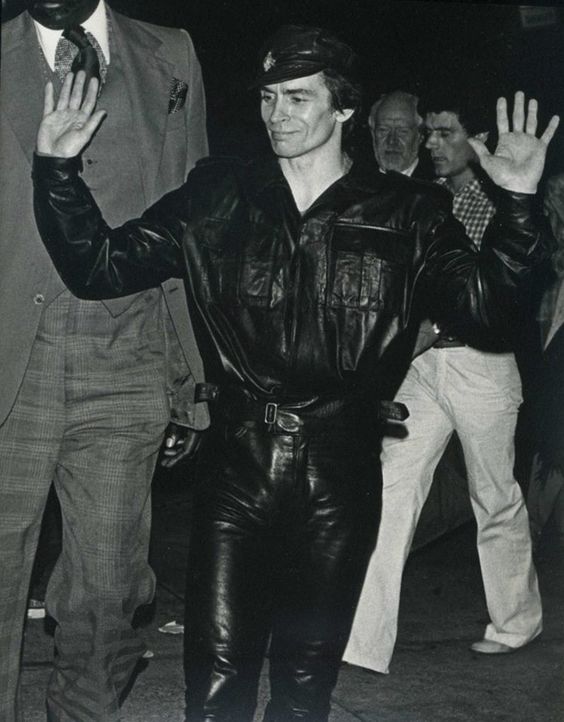

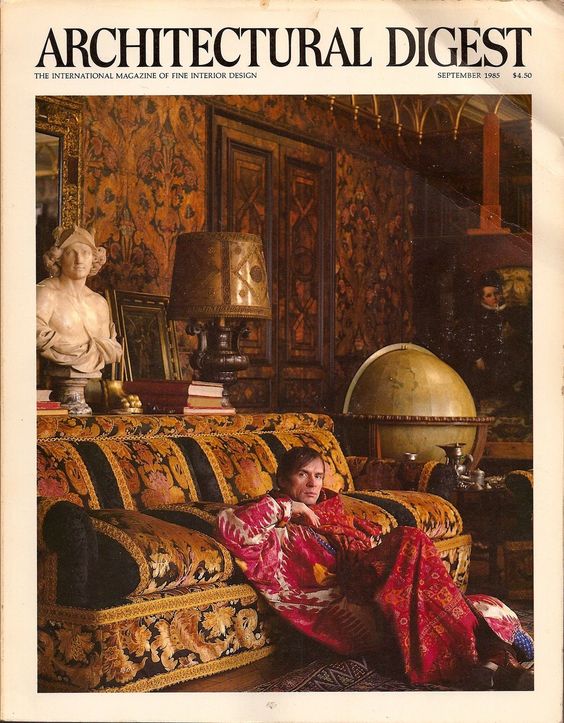

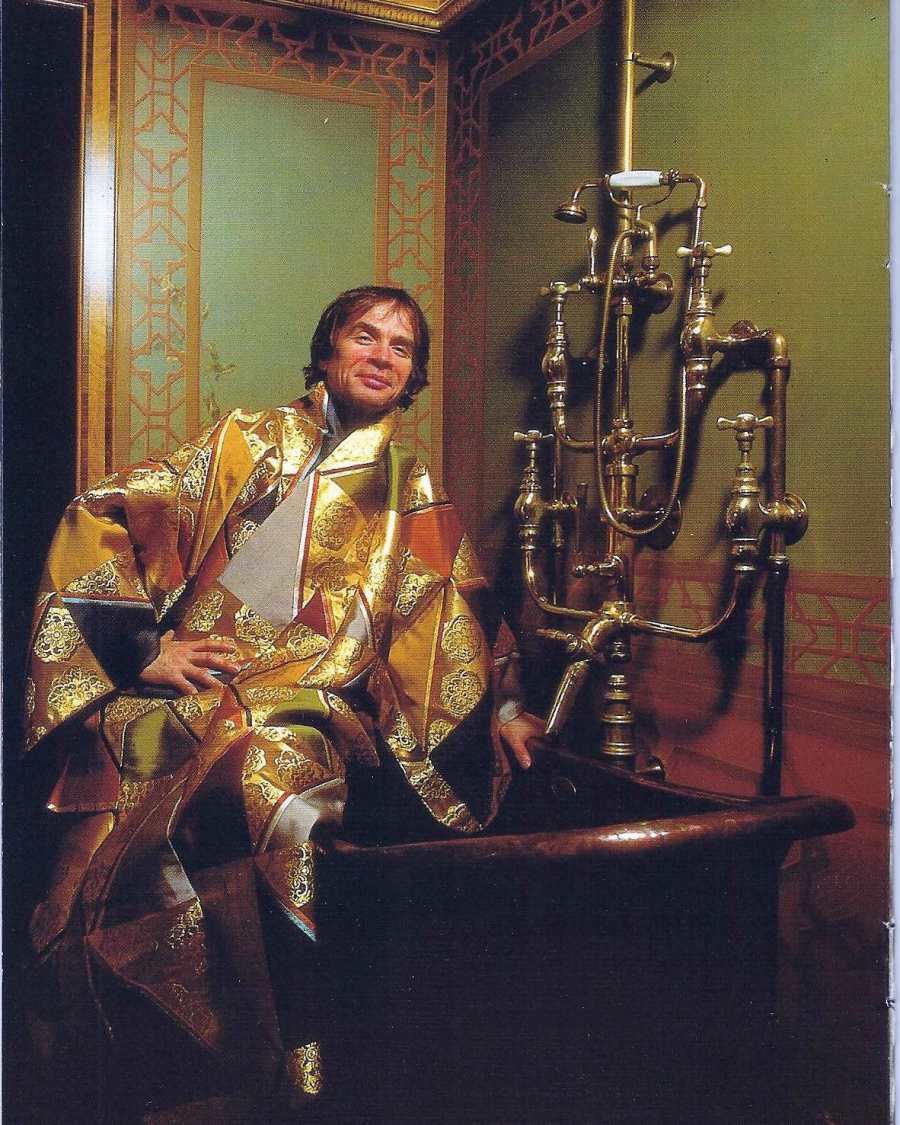

The eclecticism of his dance style, which The Times described as “bewildering,” was reflected in the range of his aesthetic. Be it casual or button-up, there was always something incredibly sensual about Nureyev’s style. It was a chunky, crocheted sweater over a bare chest. It was leg warmers, and not much else, or a leather beret with skin tight pants to match. It was Mick Jagger en pointe, with a playful slap of Robert Mapplethorpe energy.

And when he did go for a more-is-more look, it was usually in an explosion of texture, furs, and ethnic fabrics that cocooned his silhouette into that of an ancient monk, harkening back to his Eastern European roots. Architectural Digest once captured the essence of the Nureyev at home in his Paris apartment, at the height of his legacy, enveloped in layer upon layer of gold stitched silks…

Nureyev passed away from AIDS complications in 1993, at just 54 years old. Today, he’s remembered as a man who was truly one with his craft, for whom the very act of living (and dressing) was an art. We like to think that somewhere in heaven, Nureyev and Paget are putting on a fabulous performance of Swan Lake.

Sun Ra, the King of Afrofuturism

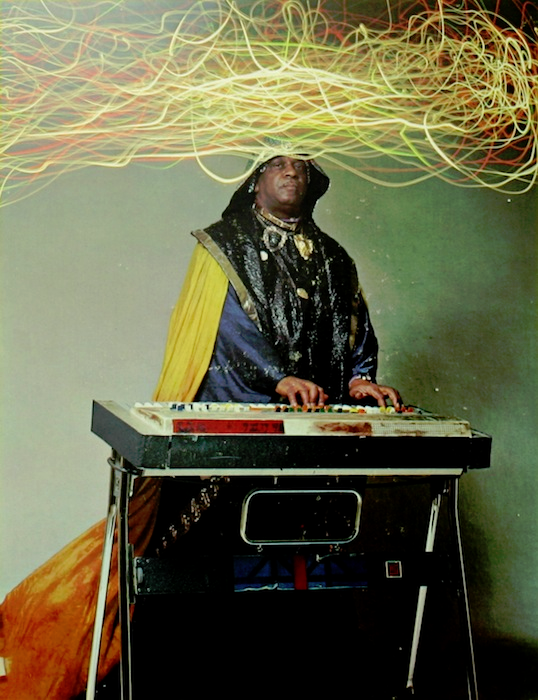

The man who proved that space is the place, Sun Ra was a renaissance man, a synth and spoken-word jazz artist who pioneered the world of the weird before Bowie, Parliament, and anyone else who wanted to go on stage with a body dipped in sequins. His band, the “Sun Ra Arkestra” (which is still playing shows today even after his passing in 1993) made up his equally fabulous kin…

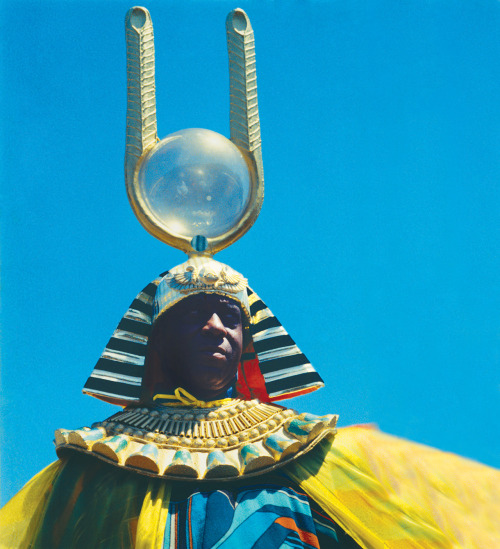

Sun Ra was born in Alabama, but always said he came from Saturn to preach peace on Earth. Né Herman Poole Blount, the performer became “Le Sony’r Ra” or Sun Ra as his musical career developed, and a major pioneer of Afrofuturism (which looks at the intersection of technology, science fiction, and philosophy through the prism of the African diaspora). Ra took inspiration from African American history, Ancient Egyptian Mysticism, and Kabbalah; Freemasonry, Black Nationalism, and numerology (just to name a few). On and off stage, he embodied a hodge podge aesthetic pulled from their philosophies, wearing long robes (we’re seeing a trend here), Egyptian-inspired headgear, and outfits ripe for an intergalactic disco.

“First of all, I express sincerity,” he said about his work, “There’s also that sense of humour, by which people sometimes learn to laugh about themselves.” The same went for his outfits – even a lampshade wasn’t off limits:

“Kings always had a court jester around,” he said, “In that way he was reminded of how ridiculous things are. I believe that nations too should have jesters, in the congress, near the president, everywhere…you could call me the jester of the Creator.”

That’s perhaps the most exciting, and precious thing about Ra’s style: it shows the dynamic nature of a revolutionary spirit. One that takes its task with gravity and with joy, proving that the two aren’t mutually exclusive (but rather, necessary) to create something of impact in a statement of social justice.

Tony Duquette, Human Jewellery Box

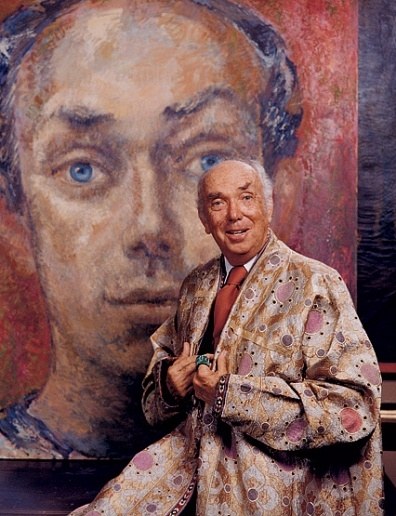

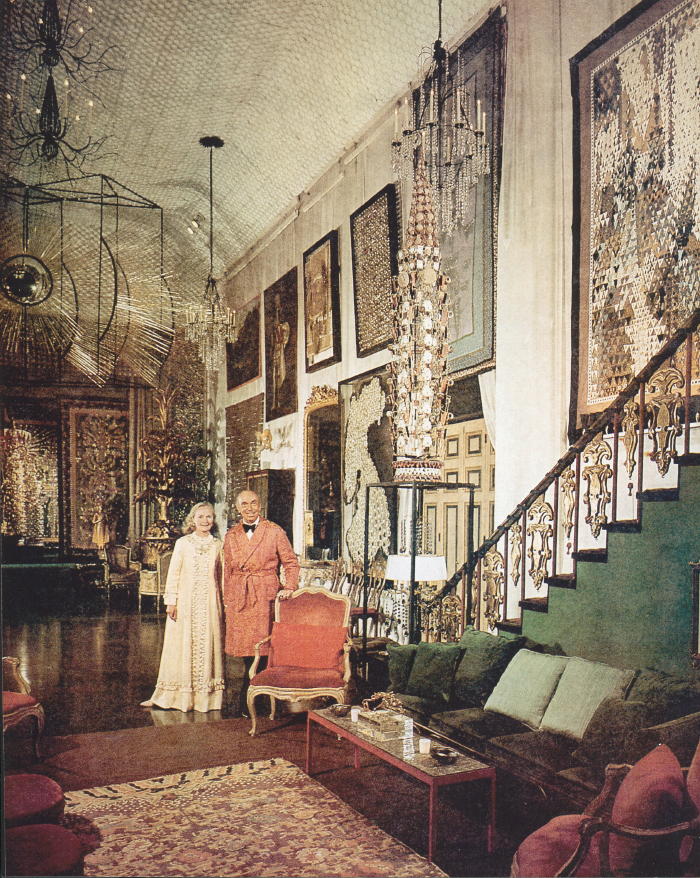

There’s a lot of magic to unpack about Tony Duquette. A whole article’s worth, in fact. The California native created the dreamiest of interiors for Hollywood sets, department stores, and private clients alike, and always with a thrifty Midas touch; he fashioned one ceiling out of pink styrofoam packaging, and salvaged massive succulents from the mid-construction, LA Dodger’s stadium.

Duquette’s personal style became an extension of his taste for thrift and fantasy. Often, he and his wife, Beegle, would play dress up with one another in fabulous outfits found at antique sales, studio backlots, and the like.

The housewarming for one of their LA properties was called. “The Bustle Ball”, and called for ladies to bedeck their derrières as creatively as possible (Duquette and his wife decided she should wear plants on her rear). In his youth, Duquette looked a bit like a black-and-white cartoon character with his big eyes and bowler hat.

But as he assumed his creative path, he began wearing larger, more extravagant robes that looked like they came right off the walls of his house.

Even his gardening outfits were equally charming in their way, with Duquette tying a little scarf around his neck just-so…

Balzac, the OG Style Spy

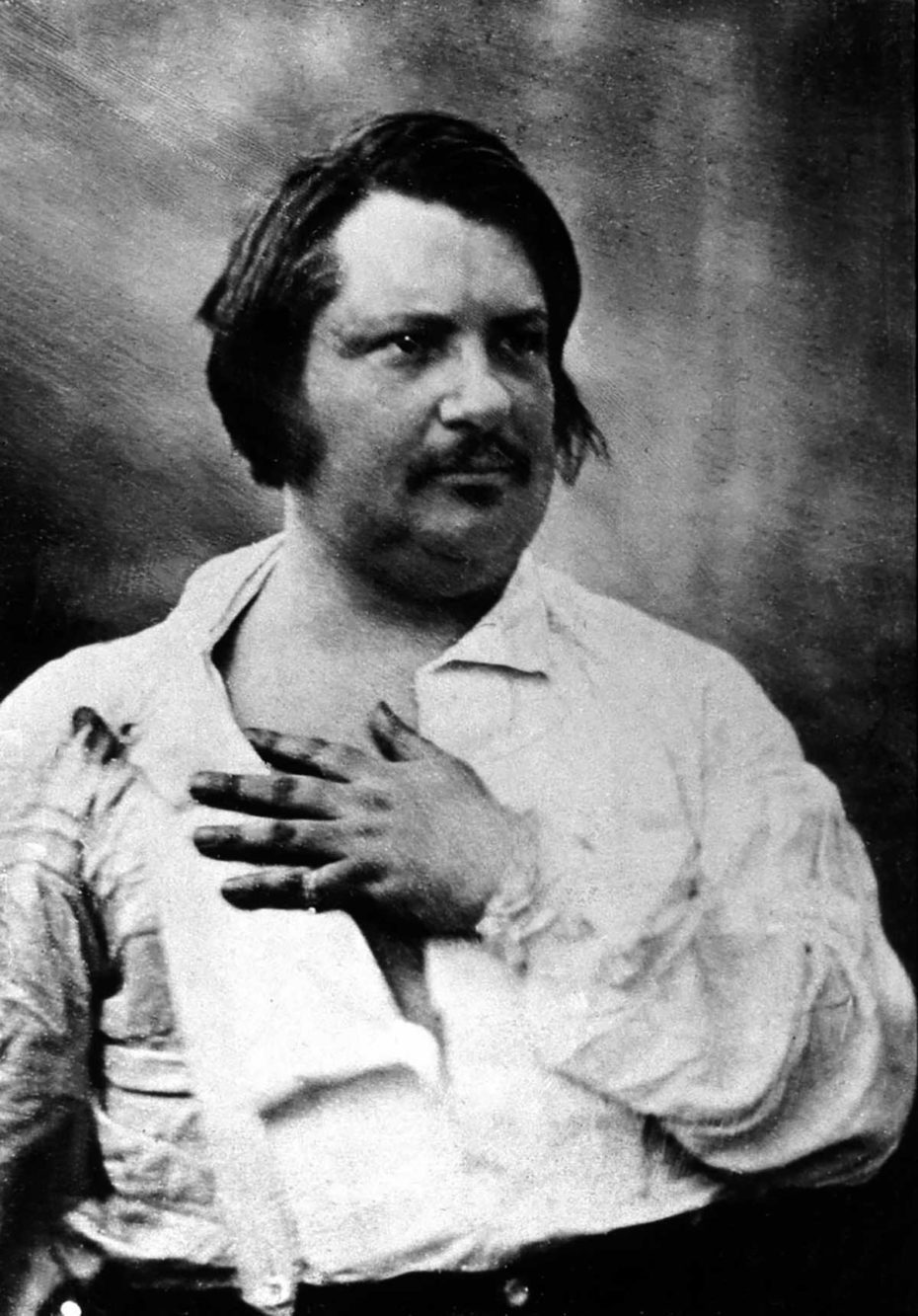

He was the fashionista to rule them all, the French writer whose tireless commitment to dress trends sets the tone (and high standard) for the rest of the men of our list, Monsieur Honoré de Balzac. “[In Paris], one observes the comedy of dress,” Balzac wrote about the city he loved, and loved to observe, “Many men, many different outfits, and many outfits, many characters!” He was the pre-influencer influencer, the OG style spy for the bustling streets of post-Napoleonic Paris. Plus, he was good with a pen, which means we were left with a colourful record of what it meant to be très chic in 19th century Europe.

Balzac wasn’t rich, but he aspired to be rich in swag. Clothes made the man in Paris, especially in a post-monarch society where the wiggle room for acquiring cultural affluence was widening. His father changed the family surname from “Balssa” to the more aristocratic sounding “de Balzac,” and when our aspiring writer moved to Paris, he commissioned the finest haberdashers, glovemakers and tailors in town for pieces that would make him pop on the boulevards; no one ordered more waistcoats (he aimed to have one for every day of the year), and no one else was strutting down the boulevard des Italiens with the same bejewelled, turquoise cane, which cost his aristocratic super-fan-turned-lover-turned-sugar-mamma the whopping contemporary equivalent of about $20,000:

Not that he considered himself a dandy, mind you. He was rather wary of the term, saying that “in making himself a dandy, a man becomes a piece of boudoir furniture.” Balzac’s sartorial choices favoured innovation, so long as it was rooted in traditional, quality craftsmanship and tailoring (men, take note). Yet, despite his on-point taste, observers said Balzac often looked a bit disheveled. He’d pass the days in his white nightgown rather than any of the elaborate outfits described in his books (guess no one worked from ye olde home back then?). Regardless, he understood the importance of the ritual of getting dressed. “The poor man covers himself, the rich man or the fool adorns himself,” he wrote, “and the elegant man gets dressed.” France, a pulse point of high fashion, was moving into the future – and Balzac was not only understanding it, but immortalising it in real time.