Revivalist sects, polyamorous communes and radical experiments in communal living – America was rife with it all in the mid 19th century – but not exactly where you might expect. Forget the Bible Belt. In western New York state, so many religious revival groups seemed to be popping up in and setting it afire with spiritual fervour in the 1800s, that they started calling it the “Burned Over District”. Mormonism, Shakers, Adventists, Spiritualists and the Millerites (some of whom went on to establish Jehovah’s Witnesses) – they can all trace their foundations back to the state of New York during a movement historians now refer to as the “Second Great Awakening”. Arguably the most controversial, curious (and curiously enduring) of them all however, is the Oneida community. From its practices of “free love” (that make the Playboy Mansion look like Disney world), the sexual mentoring, the “bible communism” and experimentations in selective breeding, to the half-a-billion-dollar silverware manufacturing giant that it later became – buckle up, because we’re about to deep dive into one of the strangest chapters in New York history.

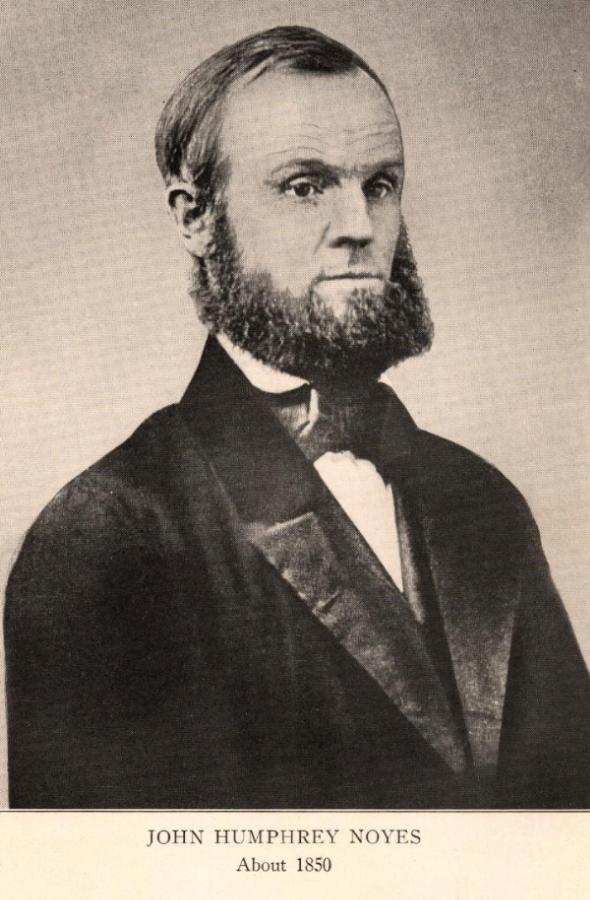

John Humphrey Noyes is the name at the core of the Oneida community, which he founded in 1848. It all began with what some of us might subscribe to as progressive ideas: gender equality, a utopian society, communal living and open marriage – all in the name of Jesus. “The new commandment is that we love one another, not by pairs, as in the world, but en masse,” he decreed, while preaching a reading of the Bible that saw no reason why Paradise shouldn’t be attainable on Earth through his philosophy of shared living. It was religious rapture siphoned through a sex positive experience. It was peace and love before Woodstock – but it all took a surprising and dark turn…

Noyes came from buttoned up stock, and was born into a posh Vermont family in 1811. When it came time for Noyes to pick his own path, he enrolled at Yale Divinity School where he encountered a radical new religious trend known as “Millenarianism” that preached a peculiar and innovative brand of thought; blurring the lines between religion and sexual desire. Revivalist ministers of the time were busy enrolling millions of new members from existing evangelical denominations, who were open to embracing a new millennial age filled with enthusiasm, emotion, and an appeal to the supernatural – you might even think of them like Millenials, if modern science, technology and the internet never came along.

Noyes didn’t exactly dig the perception of life on earth as some painful stepping stone to paradise. He adopted his own specific belief of “Perfectionism”, claiming one could reach spiritual maturity if they lived out their desires responsibly. Human sinfulness? Don’t worry about it. There was bad lust, certainly, but for Noyes there was also good lust. Declaring himself “free of sin,” however, ruffled a few feathers. Quickly ostracised in New Haven, Noyes beckoned his mounting followers to join him in a whole new experiment of living…

By the 1840s, he moved his growing community out to the city of Oneida, in New York (which takes its name from the Native American tribe of the region). He let his beard grow. He called himself, “a spiritual voyager” and told his followers to rid themselves of any frivolous earthly possessions. What began as a few dozen followers grew into a couple of hundred over the next 30 years.

In so many ways, Noyes’ community made progressive social strides. Women were allowed to choose whichever job they wished while living there. They could play sports and take up carpentry, while men were expected to take on the duties of laundry, cooking, and other domestic labours as much as their female counterparts. At a time where corseted dresses and big hairdos were a thing, women wore pants under their dresses and had short bob-like haircuts.

Sex required mutual consent, whereas in traditional marriages a woman was deemed the property or “chattle” of her husband. Noyes was building a life away from that oppression, and a community established in a sense of equality and accountability. It all took root over the sprawling Oneida estate, with its 265 acres of farmland and the Oneida mansion at the centre of it all, which women helped build alongside the men.

There were orchards, gardens, and stables. Intricate wooden follies and a gazebo dotted the yard where they played croquet, and there was a practicing orchestra group. The five story house had individual sleeping rooms, communal spaces, and a library – it was basically the poshest hippy commune you ever did see.

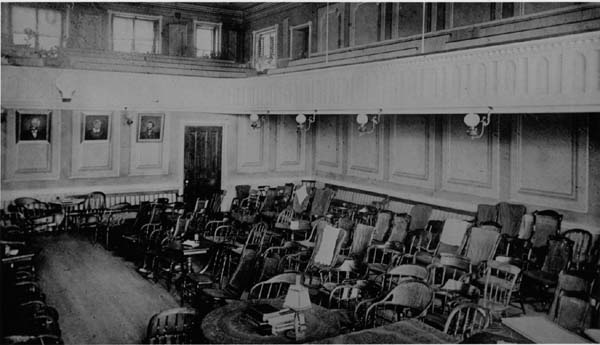

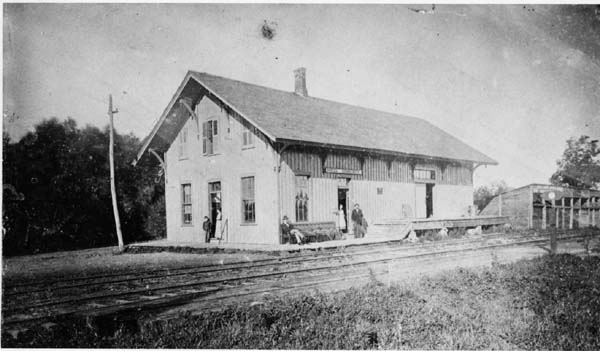

There was a seminary, and the Big Hall (or Family Hall), which was designed to be the heart of community life. The ceiling was painted with an elegant trompe l’oeil, and there was seating for some 200 people on the balcony. The colony even had its own railway station conveniently built on the property to trade with outsiders while they where on the way from New York City to Buffalo. Outsiders passing through were invited to a huge feast on the estate in an attempt to coerce them into the community.

In matters of money, everyone had to contribute to the upkeep of the operation through various household and labour tasks, or by working in one of Oneida’s small businesses. They specialised in canned fruits and vegetables, metal trap production and bag making. The progressive community attracted a large number of artisans, who had a wide range of skills to help the commune sustain itself. In the very same year Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels first met in 1844 before publishing the Communist Manifesto, the Oneidans implemented their own form of communism, pooling their personal and family assets to support the community. Scholars today use the Oneida community as their primary reference for “Bible communism”.

“We have, like a band of explorers, made a raid into uncharted territory, and we have returned, having charted our findings without injury to man, woman or child.”

John Humphrey Noyes

Unfortunately, for every step forward Oneida took two – even ten – back. The troubling history of the commune appears to have been toned down over generations, and most decedents prefer not talk about what happened at the Oneida mansion, but there are more than enough disturbing reports as to what really happened there, if you care to look.

This is your trigger warning.

Noyes preached non-monogamy, even though he had a primary partner in Harriet Holton. It was what he called a “complex marriage”, which can be summed up pretty swiftly: if you love someone, let them live (and love) freely. But its seemingly modern policies on open relationships are just the tip of the iceberg.

While Noyes encouraged birth control, it was through a rather peculiar means known as “male continence,” (coitus reservatus) which taught the community’s men how to avoid orgasm during intercourse. While this practice supposedly encouraged greater sexual satisfaction for women, the intricacies of dictating how a community should behave sexually, particularly in the Victorian era, under the control of a single man of “earthly appetites”, were far more complex.

In the Oneida community, the term for sexual intercourse was known as an “interview”, which was scheduled with Noyes and his committee’s permission at Sunday meetings, pairing different partners throughout the week to maximise genetic diversity. Despite claims of the settlement being a community of “free love”, there was reportedly just one allocated “sex room”, conveniently located next to Noyes’ quarters, overlooking the mansion’s communal area. Privacy within the community, prior to and after the act, would have likely been minimal.

Adolescent boys were paired with menopausal women, who would act as sexual “mentors” to the young teenagers, and girls as young as 12, were paired with older men in a process called “Ascending Fellowship” that put the girls under the guidance of whomever the “Central Members” believed she should be with – in short, things start sounding very Handmaid’s Tale.

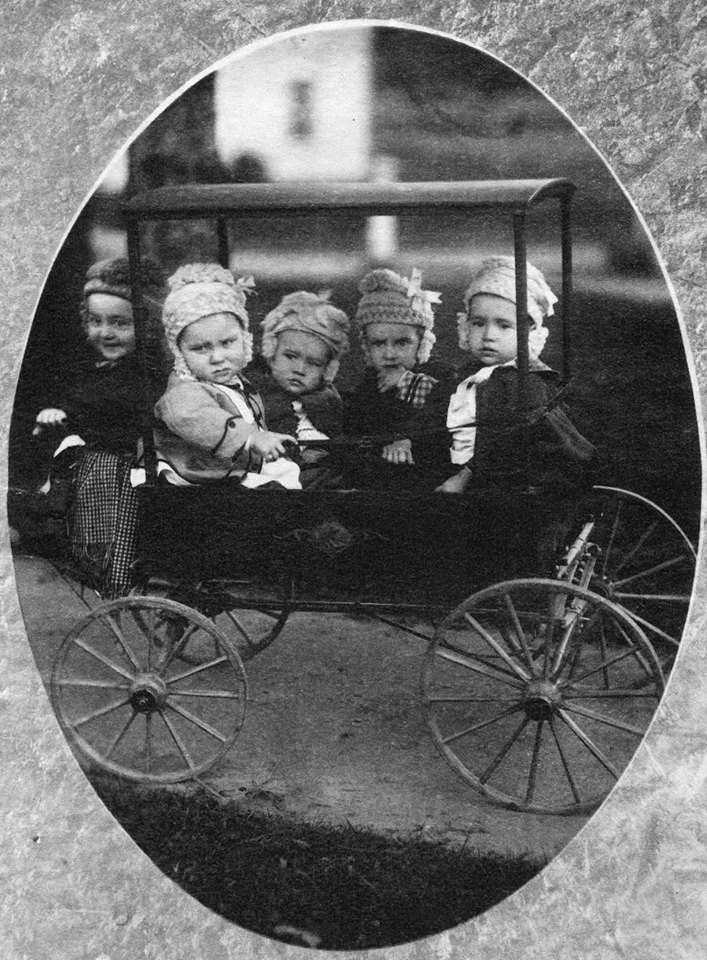

Children were produced with Noyes’ permission in a selective breeding experiment he called “stirpiculture”. In a 20 year period from 1869, somewhere around 50 children were produced from the Oneidan couples chosen by a committee on the basis of their devout “spiritual qualities”. The babies, or “stirpicults”, referred to by Noyes, would thus inherit their parents’ knack for spirituality.

Child labour too, was a thing, and parents raised their children communally. Mothers were discouraged from “fawning” too much over their own children, or spending what Noyes saw as a disproportionate amount of time with them. Children slept in their own bunkhouse on the property that had a school room on the lower level.

With Noyes and his committee being the sole authority to grant permission for “interviews” and the one space allocated for them being the one right next to his – more recent scandals in polyamorous cults can only point to more sinister goings on. Pedophilia was, and still is, a controversial subject surrounding the Oneida community. If it occurred, it happened behind closed doors at the Oneida mansion and is not officially documented, but as you can imagine, word spread fast in a place that housed so many people involved.

Numerous descendants speak of grandparents having “traumatic childhoods”, not to mention, the ones who grew up without knowing who their natural parents really were. A lot of folks around upstate and western New York today have “Noyes” as a last name, most of which are most likely descended from the man himself.

In the end, John Humphrey Noyes had taken his radical religious vision too far, even for his most loyal followers. Tensions in the community began to mount and various members began speaking out against Noyes’ emerging, “spiritual” caste system. Fearing criminal charges, Noyes fled in the middle of the night to Canada, where he learned he had a warrant out for his arrest for statutory rape.

The fate of Oneida seemed to be spiralling, especially with the US government crack down on Mormons and their more publicised polyamorous nature. Emerging new marriage laws would soon see to it that polygamous relationships were a thing of the past in New York state. Their legacy was slated to crumble, yet, in 1879 – just a year before the commune disbanded, abandoning open marriage and their spiritual utopian ideal – Oneida was doing better than ever with its production of leathers, canned goods, silk, and above all, its silverware.

“Community Silver” as they called it.

Little did their clients always know what that “community” was, and ever since, the company has been providing flatware for holidays across the country.

“It is perhaps an anomaly of modern times that [it’s become a] proper gift for newlyweds,” wrote historian John H. Martin, “but then, this is America.”

Come the mid 20th century, Oneida was the best selling silverware in the country under the direction of Noyes’ marketing-savvy son, Pierrepont, giving their collections swish European names like, “The Deauville” and “Coronation.”

When Princess Margrethe of Denmark received some Oneida for her wedding, the company took their marketing to a whole new level, printing “When a princess weds…” on their advertisements. Oneida Silverware had become the perfect wedding present, and symbol for the institution of marriage – in some ways, the polar opposite of John Humphrey Noyes’ intended vision. In other ways, the company operated under the some of the original values he first set out to instill in the Oneida community before things took a darker turn. While becoming a capitalist success, an iconic American company, Oneida still took care of its workers in a way that no other thriving businesses in the Gilded Age economy did. The executives (some 200 original members of the commune) paid themselves modest salaries, took care of the workers, built them a town, helped finance the school and supported the community at large. Pierrepont called it “industrial socialism” and there’s a great podcast by Planet Money from 2017 that delves into Oneida’s economy story of “Free Love, Free Market.”

The company continued to thrive until 2015, when it filed for bankruptcy after more than 135 years in business. Having gone public and lost its way as a “family company”, it was eaten up by foreign competitors and purchased out of bankruptcy to be combined with Anchor Hocking Glass company. The Oneida factory and offices were closed in 2017 and exists today purely as a sourcing company under the newly formed Oneida Group. Currently the headquarters are in Columbus, Ohio.

These days, the old Oneida mansion still stands with the stories of stranger days, visible in the designs of old quilts to the silhouette of the old wooden gazebo. The mansion is open year-round for self-guided and guided tours. The hall is rented out for weddings and the botanical gardens are the hotspot in town for prom photos.

Oddly enough, you can even spend the night there in one of the former community’s many bedrooms, converted to comfortable guest accommodations from $100 a night. Touted as one of the few museums in the world where you stay overnight, the reviews on platforms like Trip Advisor feel slightly surreal having taken a closer look at the venue’s complicated history, with some guests calling it a “little piece of paradise”, where they were made to feel ” part of the community”. One hopes they’re just blissfully unaware.

There’s perhaps no arguing that the perfectly-preserved mansion is one of the most unusual bed & breakfasts in New York state, if not the world. Infamous haunted hotels certainly do well attracting tourists with their gruesome history. Should you find yourself in western NY looking for a place to stop the night, don’t forget your bedtime reading from the mansion’s library where you can check out first-hand accounts from members of the community, providing one asks the person behind the desk for access to the books that reveal what it was really like living in the community. We just can’t guarantee the most peaceful night’s sleep.

You can still buy Oneida brand flatware, and learn more about planning your visit the old Community Mansion here.