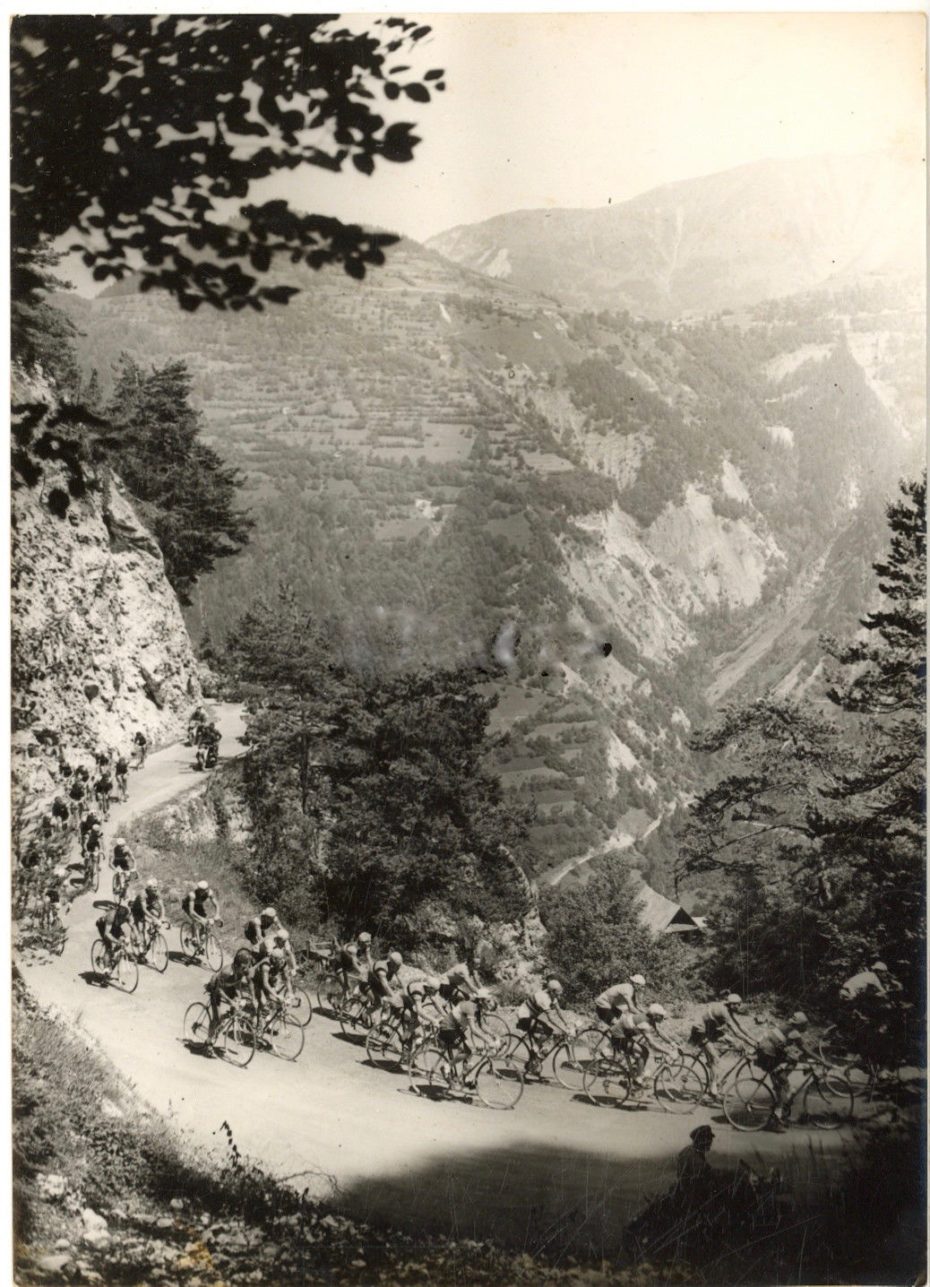

For a long time, I didn’t really “get” the appeal of the Tour de France. A bunch of men in spandex torturing themselves on two wheels, each producing enough sweat to flush a toilet 39 times? (That was one of the more unusual statistics I found floating around out there). And how does anyone take this sport seriously if almost everyone is doping their way to the finish line? Surely they must be exaggerating when they say this is the most watched annual sporting event in the world! But then I actually sat down and tried to watch it with someone who knew a thing or two about it. The first thing that happened was that my snarky comments were very quickly silenced every time the TV cameras soared above the cyclists, showing one incredible mountainscape or ridiculously scenic valley after another. There is no better advertisement for la douce France, and boy do they know it. This might be the most disgraced sporting event in the world, but it sure as heck has to be the most beautiful. It has endured two wars in Europe, huge technology changes, and more doping scandals than we can count – but the beautiful, impossible, mysterious mess that is the Tour de France is perhaps its best attribute. So as cyclists reache the finish line this weekend, I thought I’d take some time to do what I do best and find out just how messy things got over the years.

Lance Armstrong once claimed the Tour De France was “impossible to win without doping”. So how exactly did it get so impossible? When the event launched in 1903, it was first organised as a publicity stunt to increase sales for an auto magazine, edited by a guy named Henri Desgrange. A prominent cyclist and owner of a Parisian velodrome, Desrange was pretty obsessed with making the race as tough as possible.

He once said that in his ideal race, the winner would be the only one who finished. He was also of the opinion that variable gears on a bicycle were something better left to the weak. “Isn’t it better to triumph by the strength of your muscles than by the artifice of a derailleur?”, he told reporters. “We are getting soft… As for me, give me a fixed gear!”

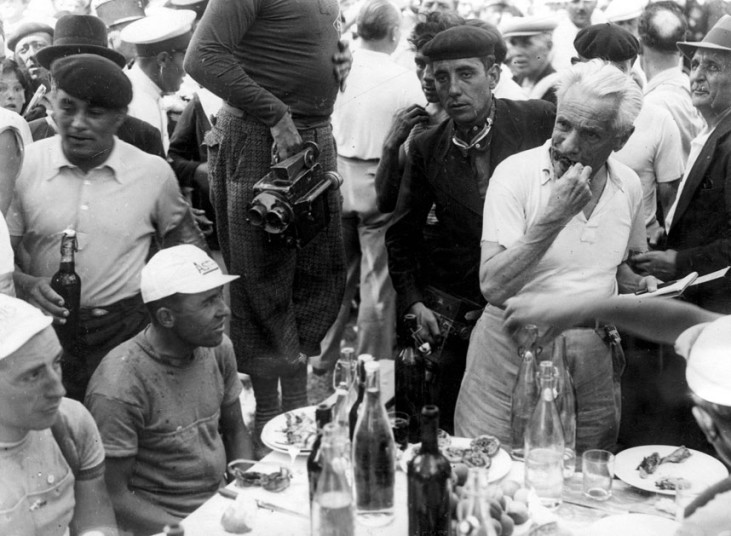

Not the gentlest of men, here he is in Bordeaux in 1935, stealing food off the breakfast plate of one of the tour’s competitors:

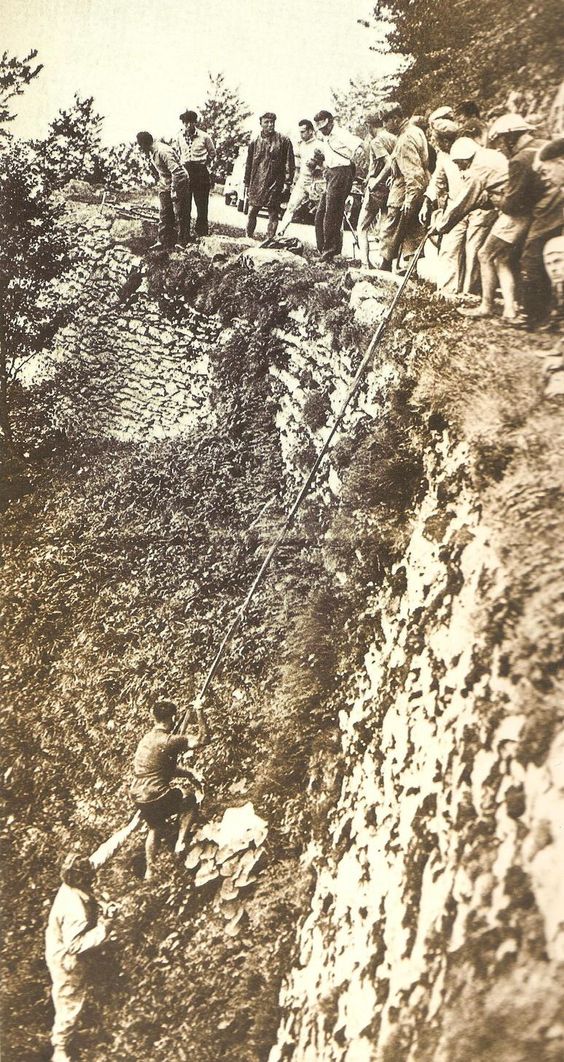

For decades, long before support vehicles were introduced to the tour, cyclists were forbidden from accepting any kind of help. In the 1913 Tour de France, Eugène Christophe’s front fork on his bike broke. He carried it 10km to the nearest blacksmith, where he used the forge to weld it back together. He was penalized 10 minutes (later reduced to three) because he had a local kid pump the bellows for him.

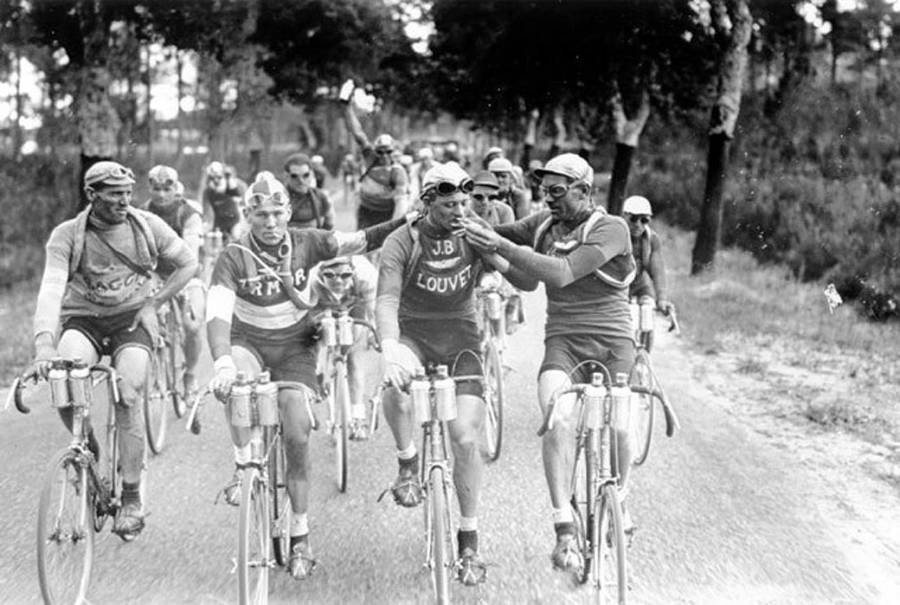

“You have no idea what the Tour de France is,” the 1923 Tour de France champion Henri Pélissier told a journalist for the Petit Parisien. “It’s a calvary … do you want to see how we keep going?” From his bag, he took out a vial to show the reporter. “That – that’s cocaine for our eyes and chloroform for our gums…”

The acceptance of drug-taking in the Tour de France was so complete by 1930 that the rule book distributed by Henri Desgrange himself, reminded riders that they would have to buy their own drugs as they would not be provided by the organisers.

Alcohol consumption to dull the pain and fatigue was standard during the first five decades of the Tour. Before the mountain stages, competing cyclists would also smoke cigarettes to “open up the lungs”, increase blood pressure and heart rate.

From the very beginning, the sport was based around substance abuse, so if you think about it – maybe Lance was just keeping up a proud Tour de France tradition?!

And we’re not just talking drug use – we’re talking about cheating in general, which was much more rampant in the early tours than it is today.

In the 1904 tour, 12 out 27 finishing riders were disqualified for taking the train instead of racing. Back then, the traffic wasn’t stopped on the roads, you had checkpoints once in a while, but very few people were actually watching, so taking the train probably wasn’t too difficult to get away with. Desgrange said he would never run another tour after that but went on to run it for another three decades.

Stories spread of riders spreading tacks on the road to delay rivals with punctures, of riders poisoning each other. One French racer Lucien Petit-Breton complained to an official that he had seen a rival hanging on to a motorcycle, only to have the cheating rider pull out a revolver.

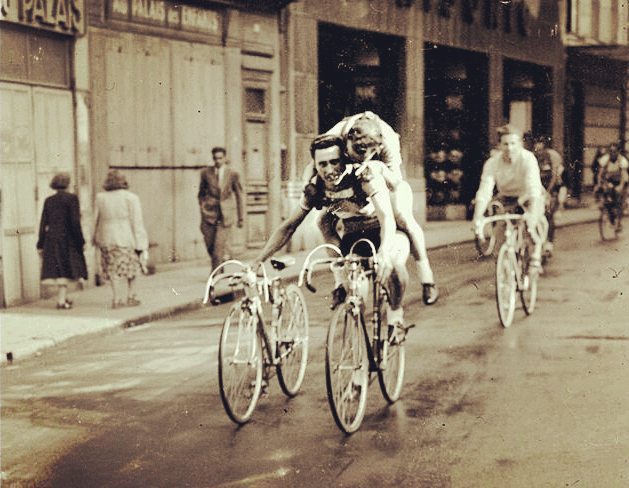

The fans got in on the cheating too.

When cyclists passed through towns, the residents wanted to help their local rider, so they’d show up with bats and chains when the riders came by, and only let their favourite pass through the blockage. Mining towns were particularly fanatical and spectators often retaliated against cyclists who had been accused of cheating. Groups of hoodlums waited in hiding for the racers, planned on beating, bottling or even knifing cyclists in the lead to help their local favourite. Many riders threw in the towel because of the fans.

The race to the finish line of the Tour de France can sometimes be so close, the slightest advantage a cyclist can get over his opponent is crucial. In the 1989 Tour de France, it was said the finish line was so close that the 2nd placed Laurent Fignon would’ve most likely won if he had cut his hair.

As for last place? Funnily enough, some riders actually compete for that too.

In the Tour de France, the rider who finishes last is accorded the distinction of lanterne rouge – in reference to the red lanterns traditionally hung from the caboose of a train so dispatchers can see in the dark if the last car of the train is still there as it goes by. Last place finishers in the Tour de France are given a red lantern in honor of their failure and their courage for not dropping out along the way.

Over the years, the notoriety it affords made last place an attractive alternative to finishing somewhere in the middle. The rider who comes last is remembered while those a few places ahead are often forgotten and the revenue that the recipient of the red lantern might generate from appearance fees can make defeat taste a little sweeter.

While the Tour de France of today is reportedly set to be the “cleanest” yet – here we are thinking – maybe the mess is what makes it so good after all?

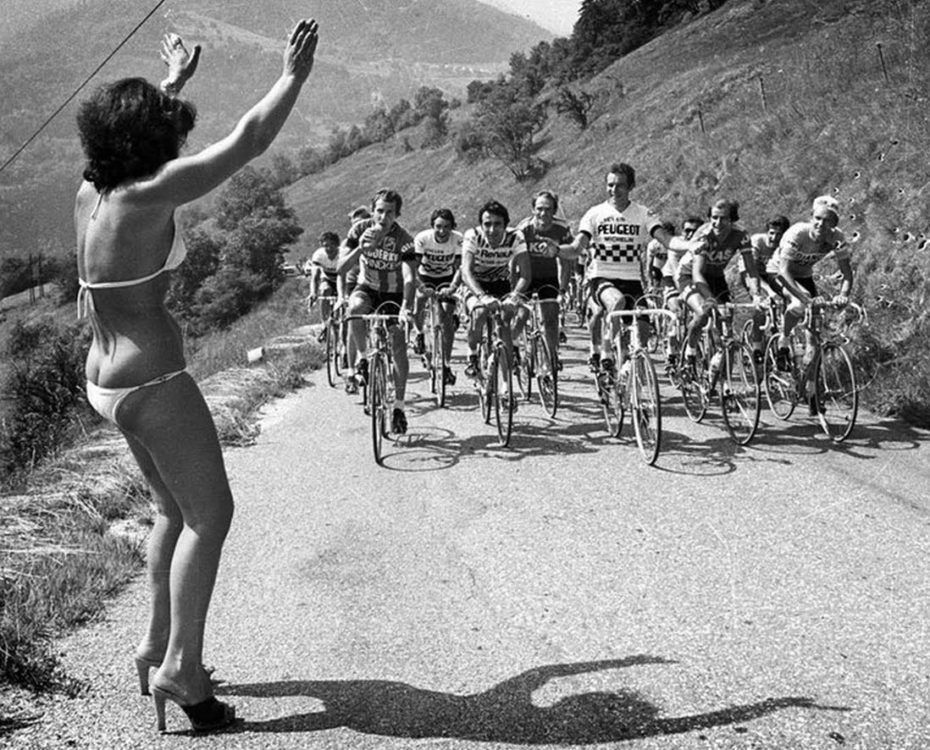

Yes, it could use some women in the race for the 21st century. Also, we may never know how all those chaps avoid damaging their man parts with that much saddle action. And sure, you’ve gotta be bat sh*t insane to sign up to this race in the first place. But join me next time won’t you, in sitting down with a bottle of your strongest French red wine to tune into the cyclists as they reach the end of the most disgraceful, drama-filled, dirty sporting event the world has ever seen. Worst case, you’ll doze off, dreaming of those postcard views of France…