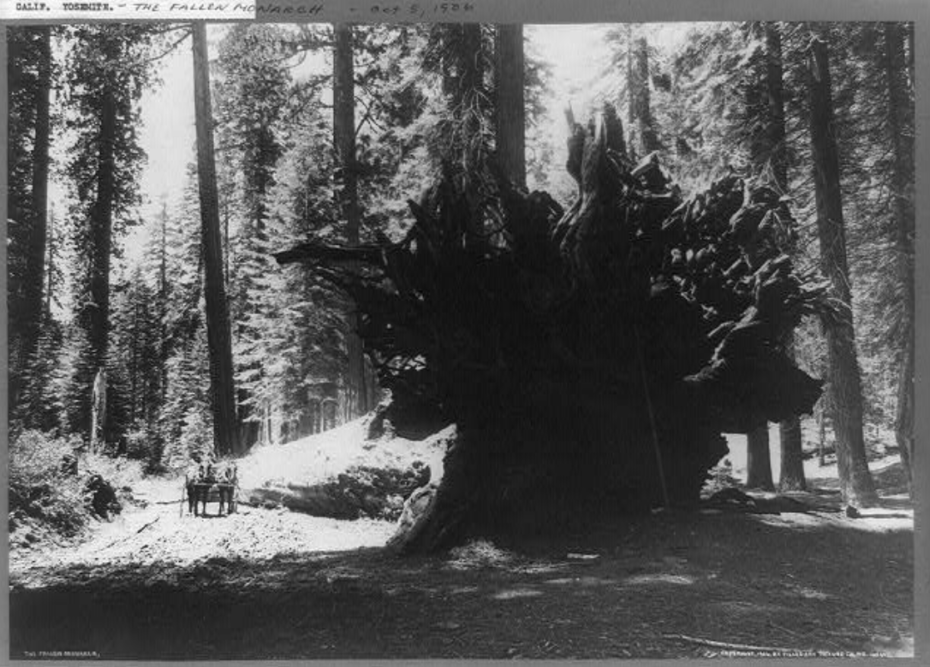

There are trees, and then there are trees out west. “Ancient sequoias,” “Mammoths,” or “Big Trees,” as John Muir liked to say – the nicknames varied, but the trees’ contribution the grandeur of the storied West Coast remained the same. Pioneers worked, breathed, and seriously lived in the darn things. Improbable today, but common in the late 19th century, houses carved inside massive tree stumps were a staple of life in states like Oregon, Washington and California, where the lumber industry was booming and leaving a veritable sea of beheaded trees in its wake. Crafty by nature, the pioneers took to those wastelands and upcycled the stumps into homes, dancefloors, hotels – you name it. Ladies ‘n gents, meet the original tiny houses…

We know the US is young. But sometimes, we forget just how much younger the West Coast is than the rest of it. After the Civil War, new railroads were cast into the continent like landlines to the promise land of California – and that sunny future got even sparklier with the onset of the Gold Rush. Still, you had to be a bit of an oddball to head out West. You had to leave behind your friends, your possessions, and risk death on the daily. You had to have a staunch character, and one that was still willing to take a huge gamble – crazy, with a streak of the poet.

In the words of Joan Didion, herself a Donner-Era descendant, you had to be dead-set on survival. “The mind is troubled [here],” she said, “by some buried suspicion that things better work here, because here, beneath the immense bleached sky, is where we run out of continent.” But not trees.

Known as the sentinels of the West, these giants were kind of like mythical beasts for the rest of the country. Folks wrote home with stories both grand and heartbreaking, of new lives lost and found amongst the Jurassic trees (the oldest sequoia fossil dates 135 million years back). Not to mention, stories of gold – and where there is is gold, there is industry, which meant that the undertaking of logging the trees became urgent. The logs were so large, they had to travel down through rivers as makeshift rafts.

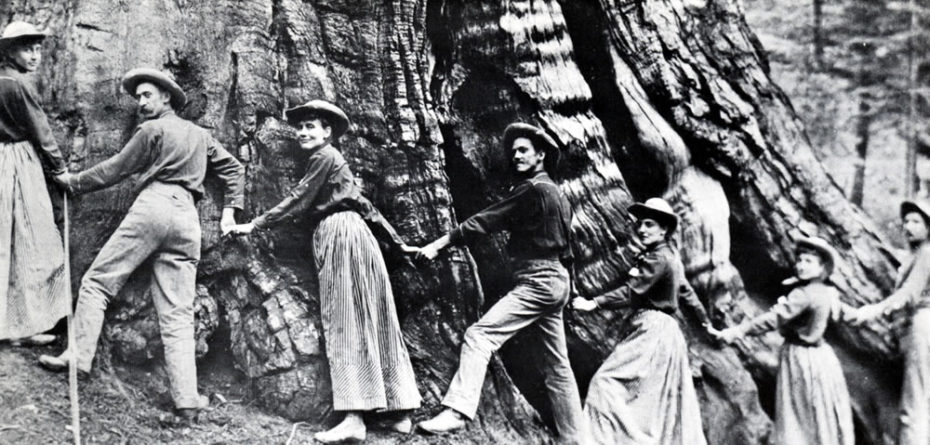

It could take men a month to fell a 1,000-yr-old sequoia, and when the deed was done, it often became a dance floor….

To our eyes today, it’s a scene equal parts whimsical and cringe-worthy. As an endangered species, its unsettling to see people dancing over the graves of the ancient beauties. But in many cases, they were simply picking up where loggers left off, making the best out of the “unusable” bits of wood (the grain warps at the base).

As one paper wrote in the 1850s about a stump dance, “[An] excellent spring floor was laid between the hotel and the Big Stump and both the floor and stump covered by an arbor of cedar boughs beautifully arranged with many candles among branches…. The scene was romantic and beautiful beyond description.” The only complaints according to the ladies? No spring in the “floor,” apparently.

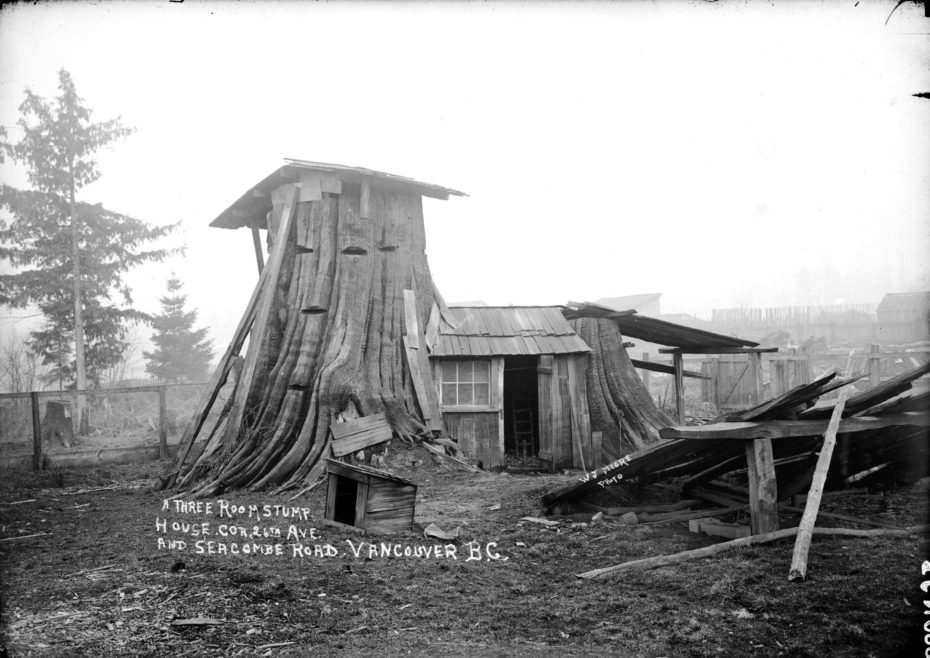

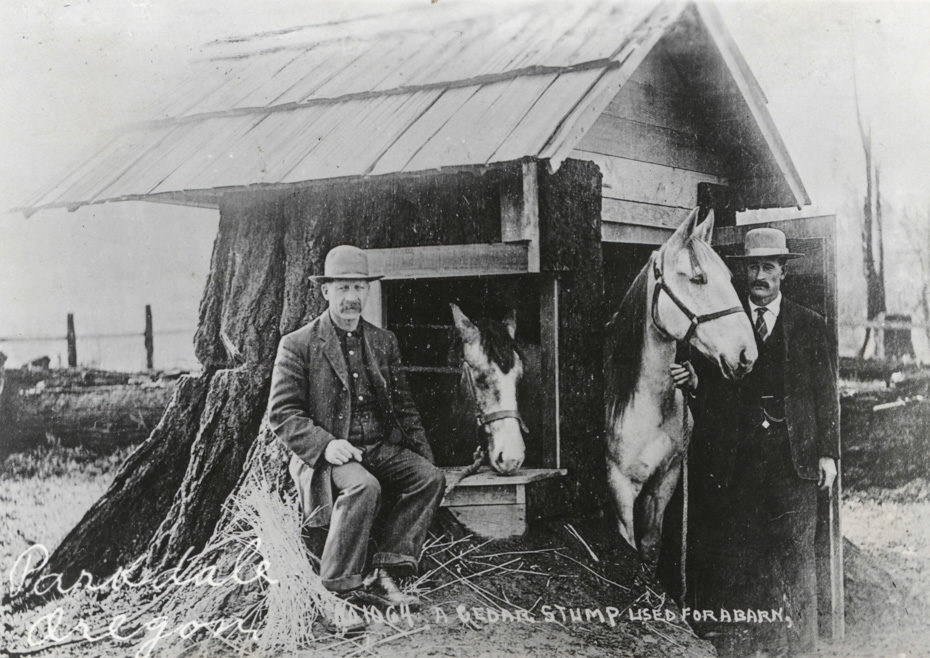

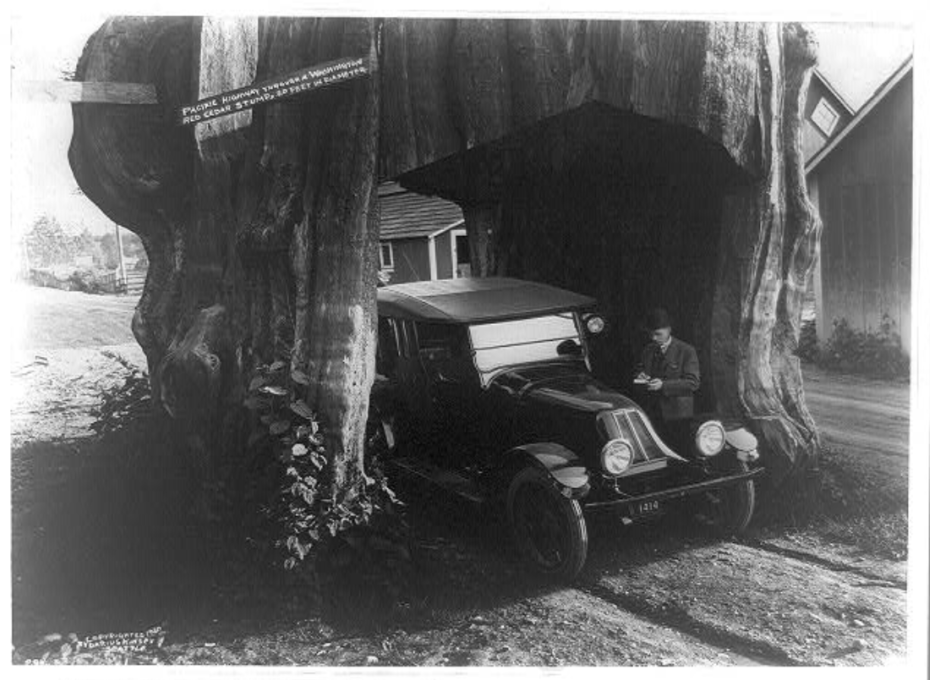

Stumps became sheds, huts, and houses. They became a place to store your animals, provisions, and anything else that needed the kind of security the walls of a tree that could grow over 30ft (over 9 metres) wide. They were so wide, and so solid, you could carve a tunnel through them. Most importantly? They were free.

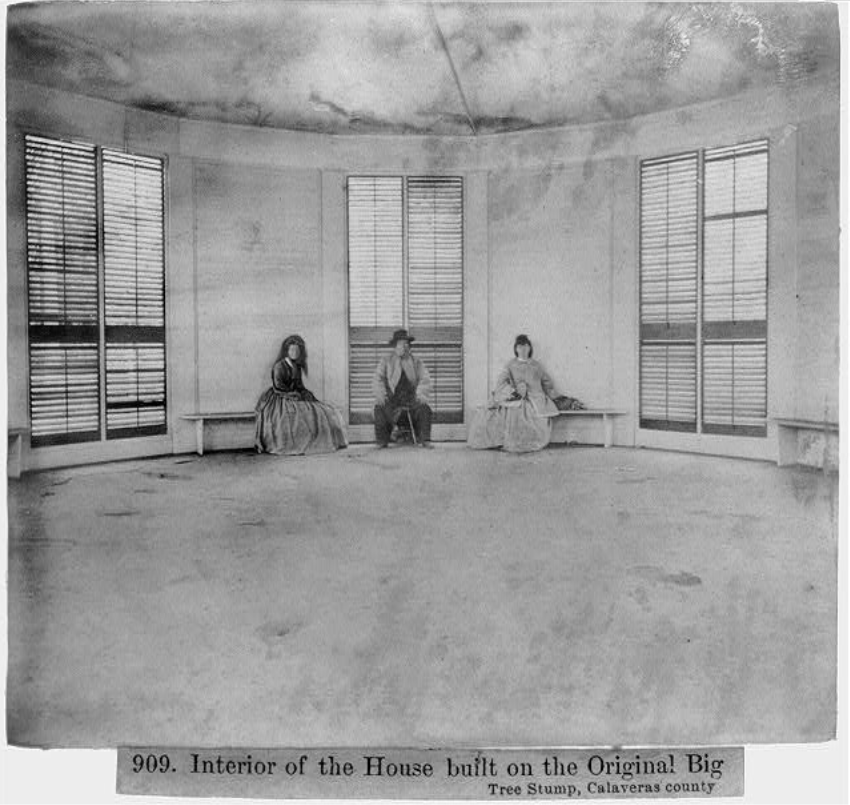

They weren’t always shabby chic abodes either. One stump-turned-dance hall in Calveras, California, looked very modern given its setting in the middle of the woods. It even became a hotel. “Mr. A.S. Haynes [is] proprietor of the Big Tree Grove,” wrote The San Andreas Independent in 1858, “has re-fitted and re-furnished his Hotel for the accommodation of customers in a neat and comfortable style. As a fashionable resort, the Hotel is equal to any in the State, and parties visiting the Grove, can go, assured that everything necessary for health or recreation is provided in a liberal manner.”

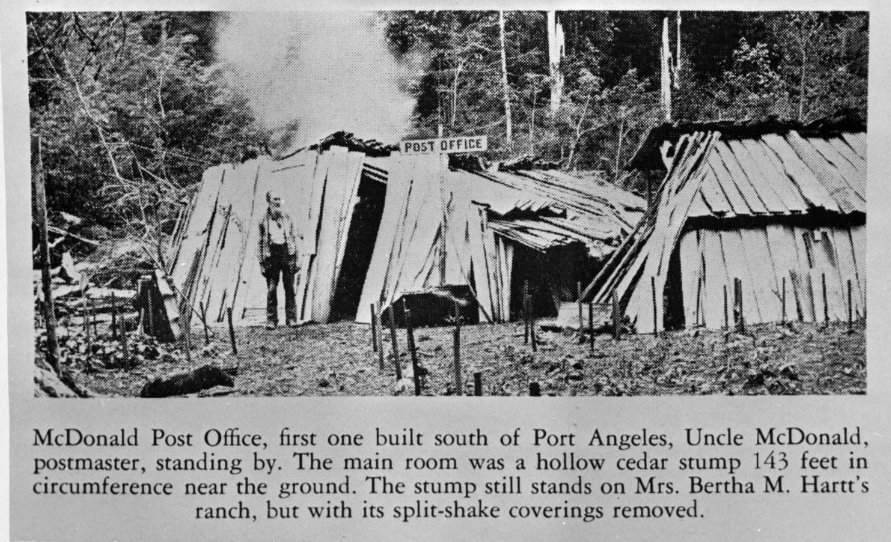

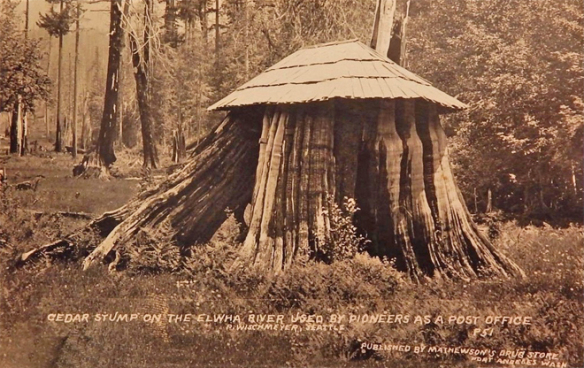

Stumps were kind of becoming all the rage, and a means for bragging rights from travellers. The very first US Post Office in the northern Olympic Peninsula was set up in a stump in 1892 by William D. McDonald; positioned on the eastern side of the Elwha River, it became secure lodging for a post master in one of the furthest reaches of the country:

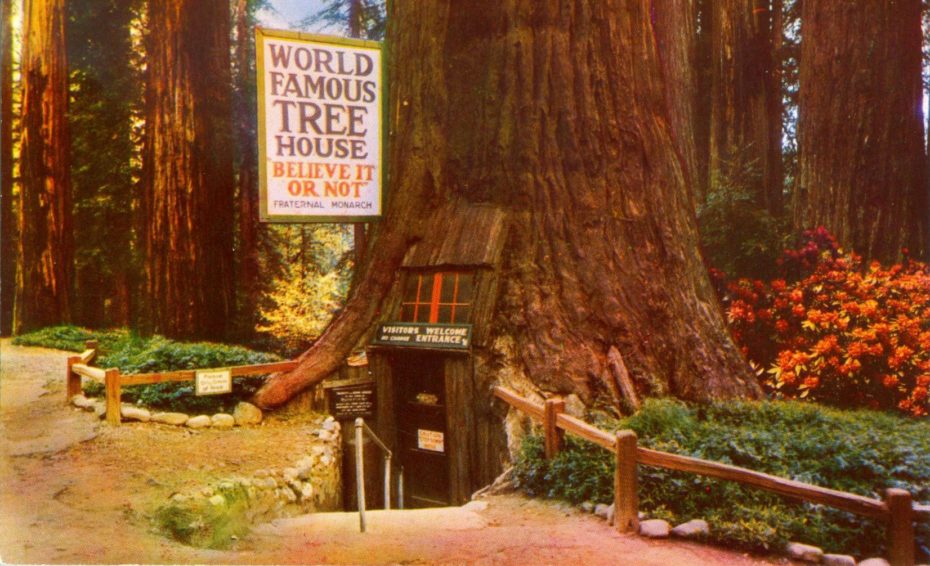

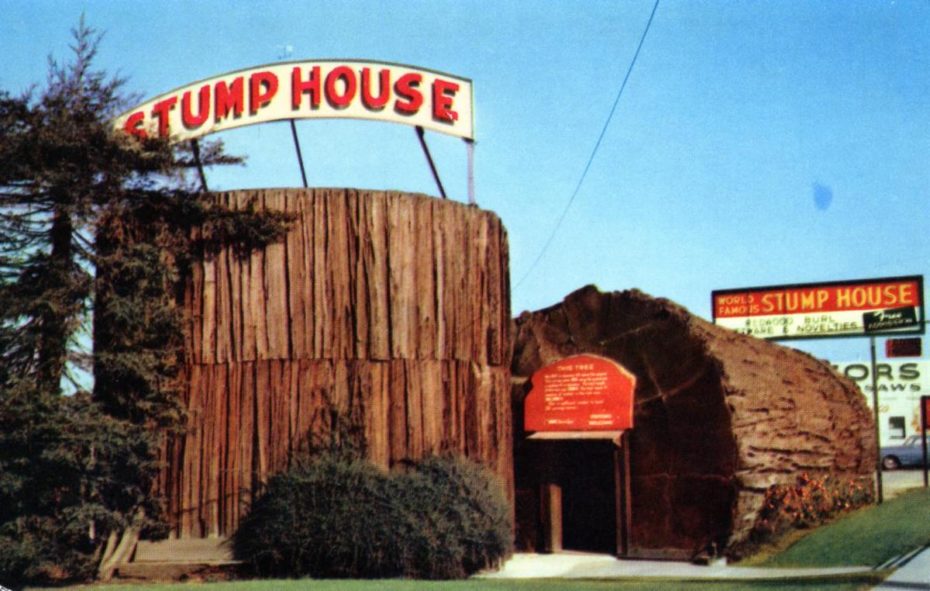

They were also a natural fit as roadside attractions in California. There was the famous “Stump House” along the road in Eureka (it existed into the 1990s) complete with a giant, hollowed out log, and “The Eternal Tree House” in Redcrest, which still has its own restaurant and gift shop. In Porterville, an old stump attraction is now positioned in the aptly named, “Big Stump Trailer Park.”

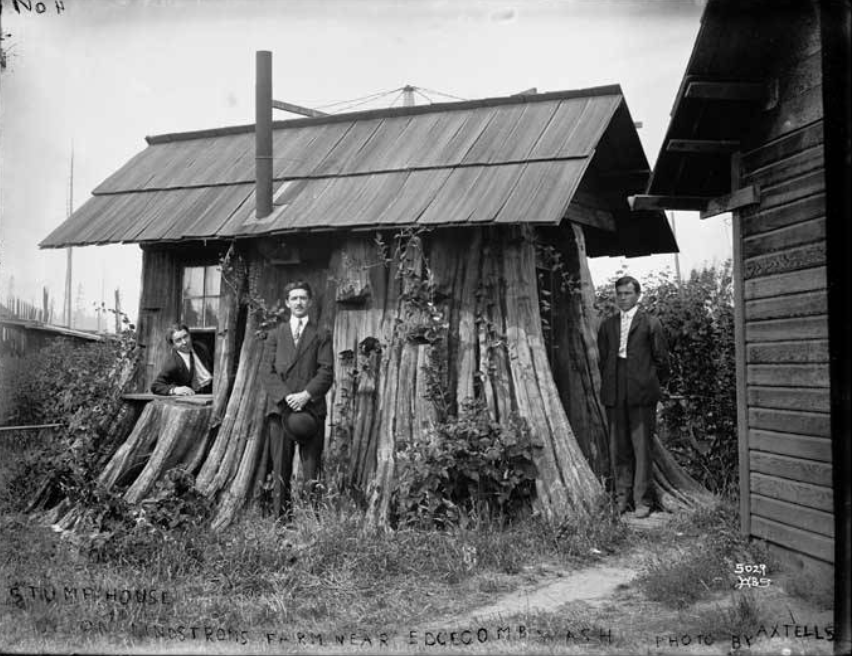

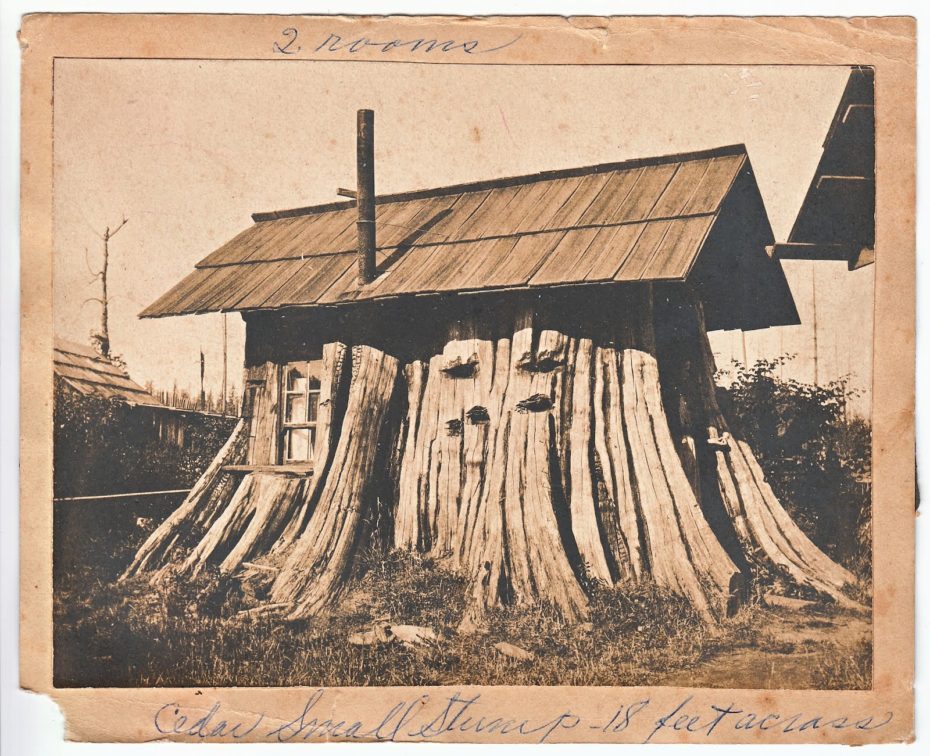

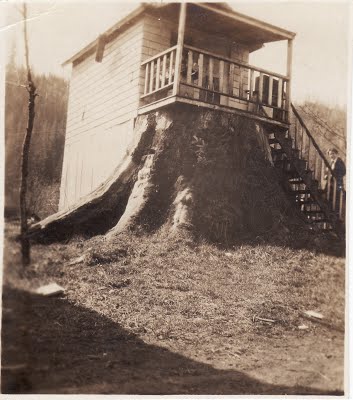

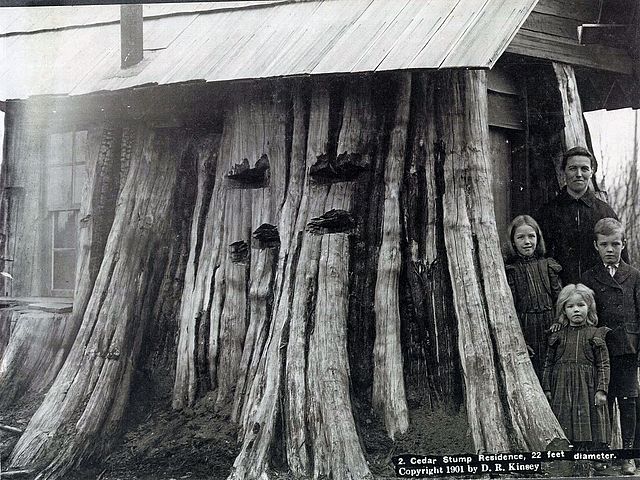

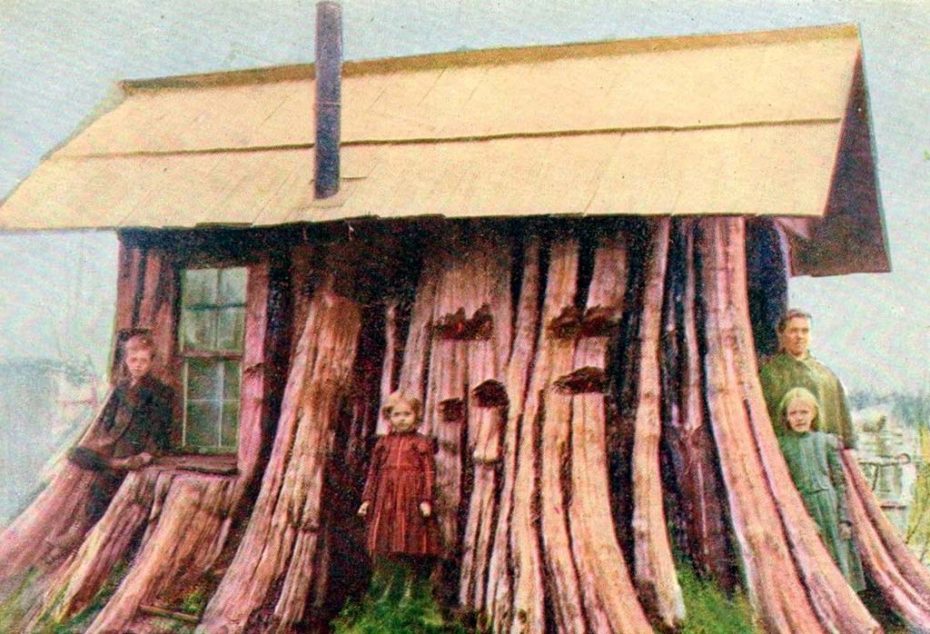

Then there’s the stump story that really tugged at our heartstrings: the tale of Cedar Stump house in Edgecomb, Washington. It was build by an early Swedish immigrant named Gustav Erik Vilhem Lennstrom. “When [my grandfather] came to this country, he made a beeline for the Pacific Northwest,” one of his descendants recalled for the Seattle Times in the 1940s, “[He] bought this acreage at Edgecomb, a stump farm. It had been logged off but the stumps still stood. It was not land that you could cultivate. About all you could do was raise dairy cattle. And that’s what he made a living at.” Gustave gave the stump a roof, and a stove to warm his little family during the winters. It’s said that even when a proper house was built on the land, Gustav preferred the quiet of the stump.

At the turn of the century, a prominent photographer named Darius Kinsey snapped some shot of the home – and from there, it too became a beloved novelty of the area. “Inside it is one good-sized room, which is boarded up and neatly papered and made as comfortable as any apartment could possibly be made,” wrote the Skagit County Times in 1903, “The walls inside slant inward at the top, which gives one the impression rather that it is an upstairs room, otherwise it is not different from any other room.” After Gustav’s passing, the Cedar Stump House scrambled to save itself. The new landowners cut it up like cake, and stored it for eventual reassembling at a new location – but it rotted in limbo.

The stump house craze will forever embody the giddy, pre-environmentalism landscape of the West’s history, and the fight continues to keep the trees’ remaining habitats safe today. Luckily, trees also have a hidden superpower for playing dead, and giant sequoias and redwoods will continue to grow sprouts from their stumps. Hell, in some cases, a wounded tree’s roots can graft together with its neighbour’s to stay alive, sharing its nutrients and water. Life, as they say, finds a way.

You can visit a preserved stump dance “hall” at the Stillaguamish Valley Pioneer Museum, check out the Big Stump Trailer Park, and learn more about lending a hand in giant sequoia preservation here.