The rise of accessibility to medicine in the 19th century was a beautiful thing, but it also opened the gates to a deluge of medical scams and quackery. If you were lucky, they were harmless scams. But more often than not, treatments included addictive and life threatening ingredients. Today, we’re diving into a brief compendium of medical quackery, from the ye olde to not-so-very-long ago cure-alls, and thanking our lucky stars that we never brushed our teeth with radium, or lit up a pack of “Asthma Cigarettes,” all the while wondering: would I have fallen for it?

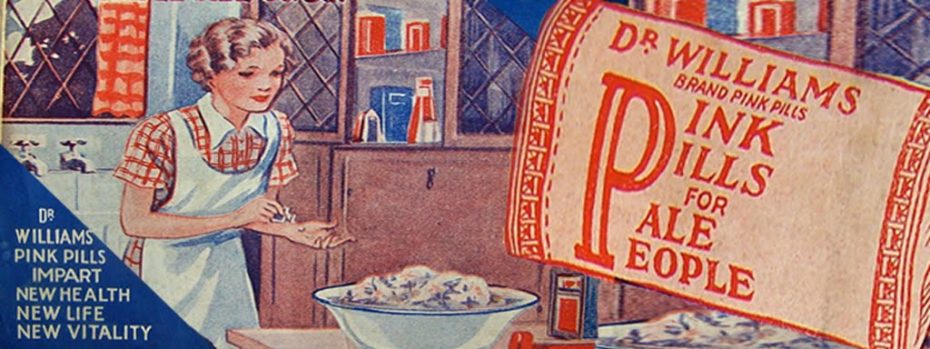

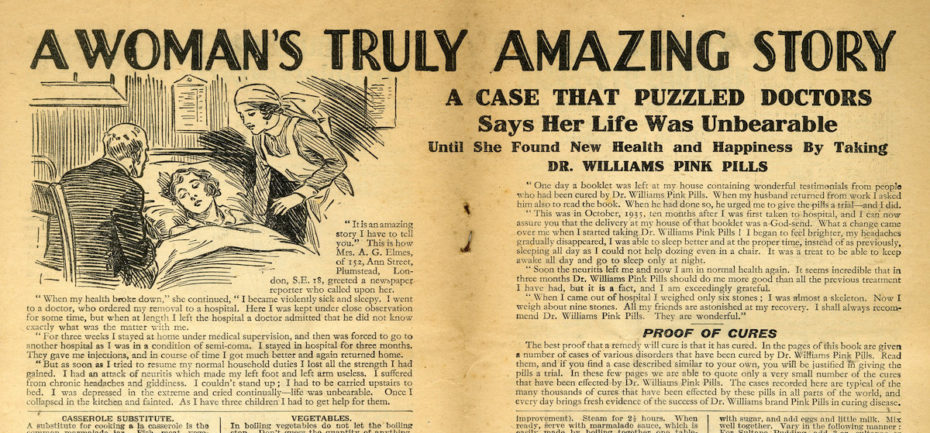

Pink Pills for Pale People

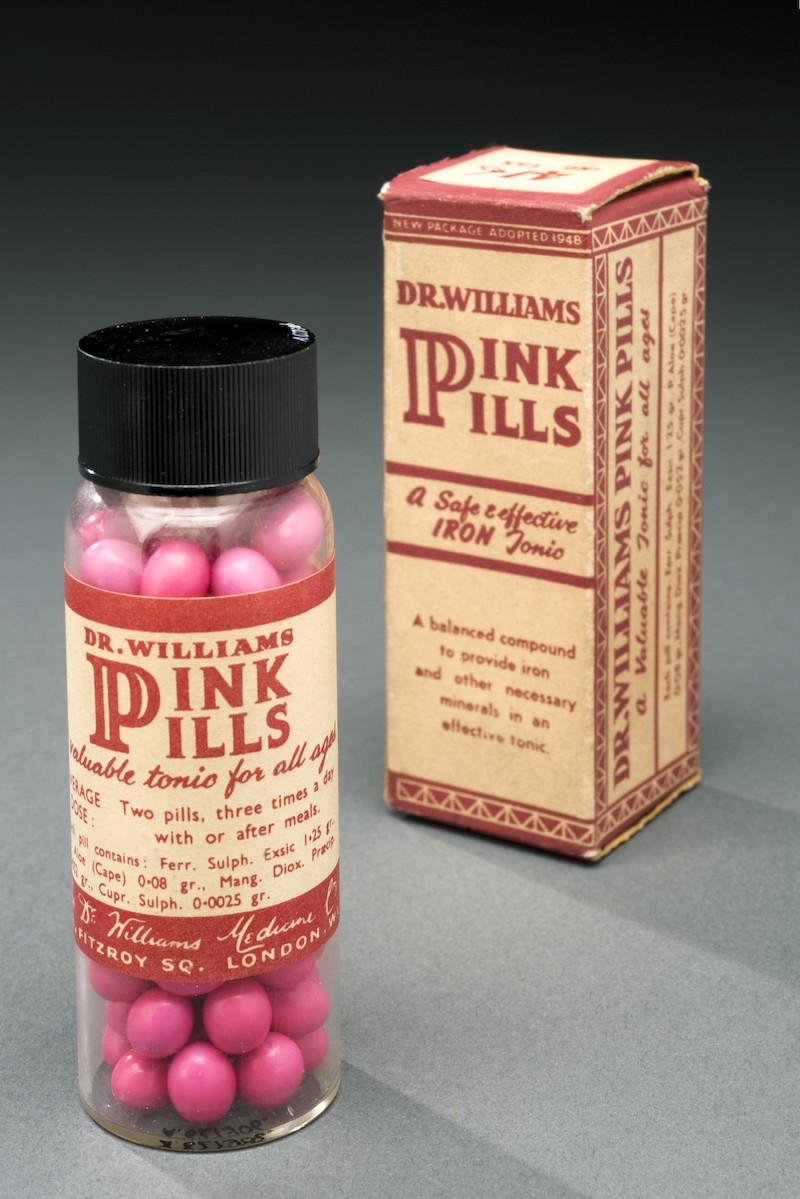

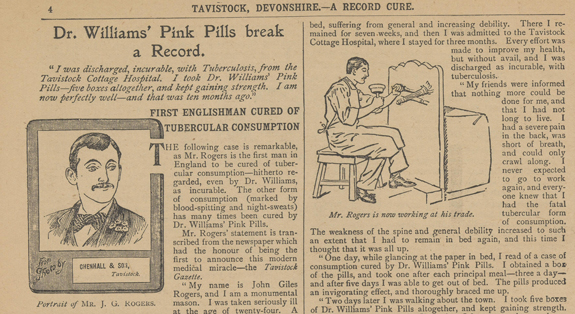

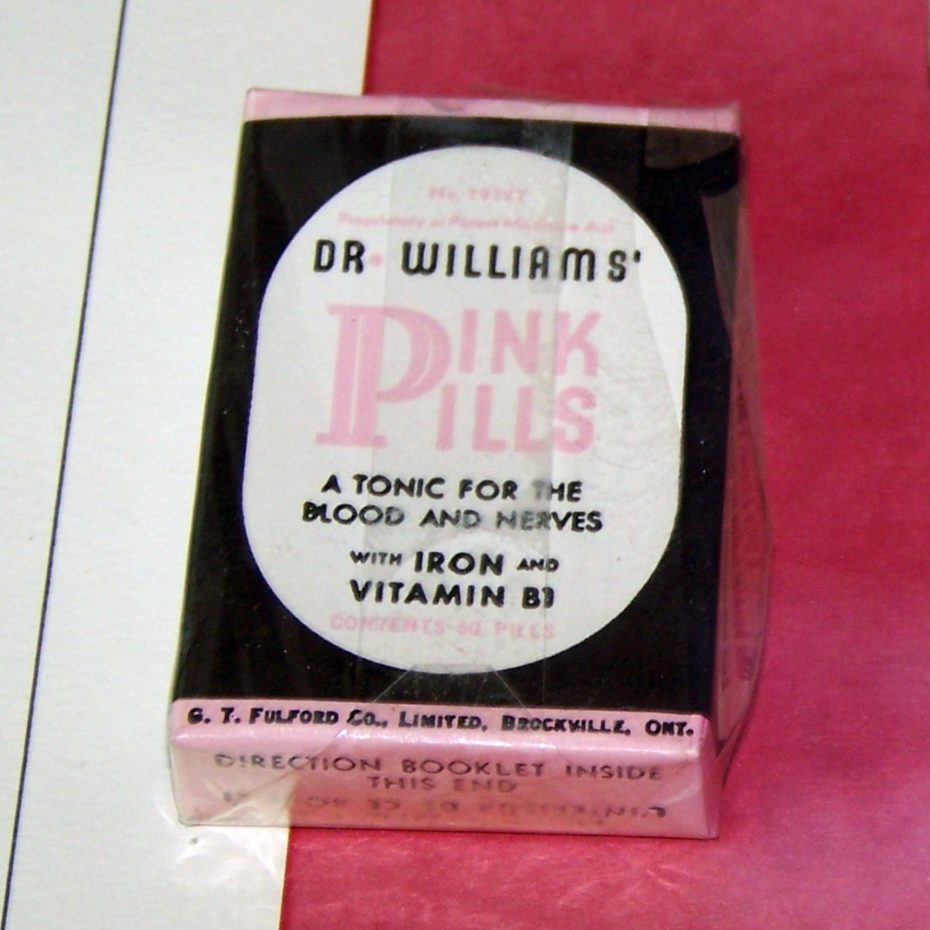

It was advertised in almost 100 countries, raked in millions of dollars, and was on the market from roughly 1890 to 1970. How, and why? Well, “Dr. Williams’ Pink Pills” were meant to be the the sugary cure-all for the ailments of modern life. Especially what Southeast Asian historian Mary Kilcline Cody called, “the White Man’s burden” of British colonists. (Yeah. We’re screaming too.)

“If the invulnerability magic of the sola topi, the spine pad and the cholera belt failed,” she wrote, “Europeans could always rely on the Pink Pills to alleviate the pressures of bearing the white man’s burden.” At the turn-of-the-century, disease – notably, Tuberculosis – was rampant in the colonies, and the Dr. William’s Pink Pills were manufactured by Williams Medicine Company, the trading arm of G. T. Fulford & Company, and marketed as “The Queen’s Gift” to the people, “an iron rich tonic for the blood and nerves to treat anaemia, clinical depression, poor appetite and lack of energy.”

As far as ingredients go, they were fairly harmless (in comparison with other concoctions in our article), and included “sulphate of iron, potassium carbonate, magnesia, powdered liquorice, and sugar” according to the British Medical Association. Unfortunately, the Association’s discovery of the oxidisation of the iron sulphate in the pills revealed how carelessly they were being prepared – but hey, they were coated in pink sugar so how bad could it be?

The “Pink Pills” were above all an early example of the increasingly creative, relentless marketing tactics of the 20th century; they were formally endorsed by everyone from a reverend to a songwriter named Benny Bell (whether or not there was ever even a real Dr. Williams is up for debate), and touted in ad after ad of richly endorsed testimonials by friends of the pills’ backer, the powerful, politician-heavy Fulford Family.

The pills went though advertising and formulaic changes over the years – and at one point included the laxative, aloe – until they were production stopped in the 1970s because, well, they didn’t really do anything miraculous. Curiously, you can still visit the sprawling Fulford Family house in Ontario, Canada to see the fruits of all that Pink Pill money…

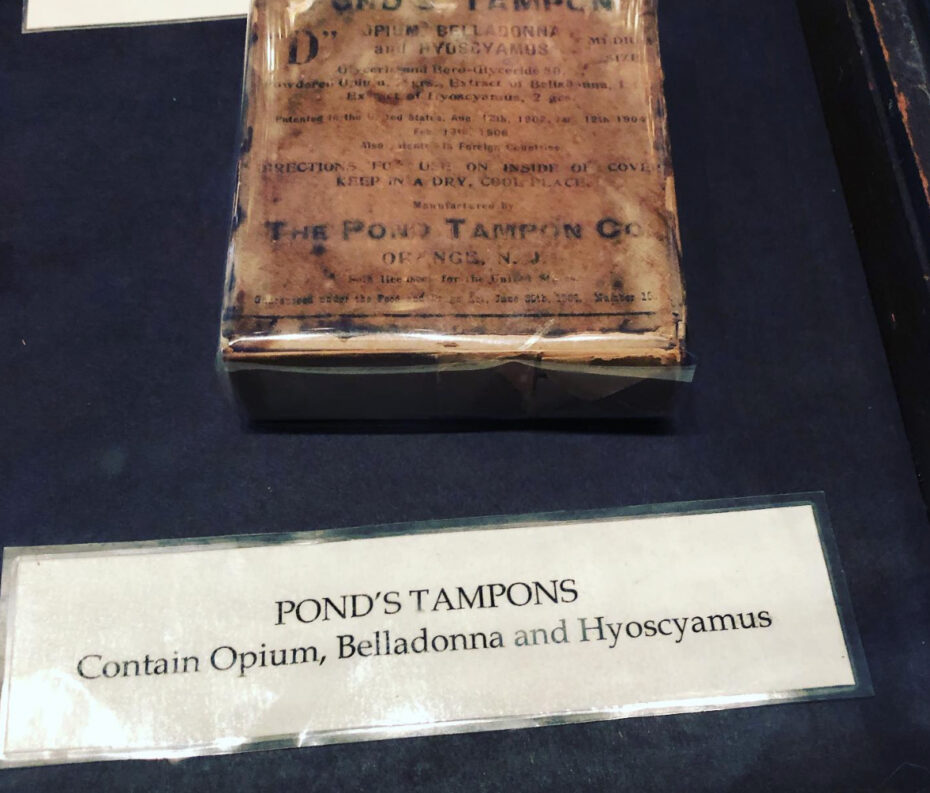

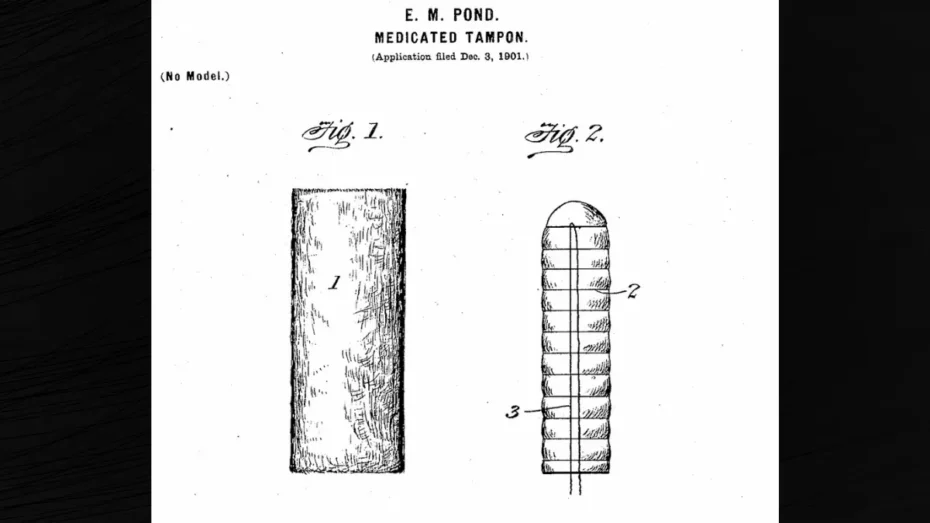

Opium soaked Medicated Tampons

In the early 20th century, Pond’s medicated tampons were soaked in opium, belladonna, and hyoscyamus in order to relieve menstrual pain. The above example comes from the Pharmacy Museum in New Orleans. Learn more about their collection here: https://pharmacymuseum.org

Patented in the United States in 1902, by Edmund Morse Pond — a Rutland, Vermont surgeon and inventor, that 1902 patent described a “medicated tampon,” and stated:

My invention has relation to improvements in surgical appliances in the nature of suppositories, tampons and capsules for internal application and treatment of the uterine system or of the rectum; and the object is to provide a compressible and expansible roll or cylinder composed of an absorbent material which in its compressed form may be applied within a cavity of the body and when so applied may be released from compression and automatically expand…

The interior of the body may be cored out…to afford room for a medical substance, which will saturate the material and eventually reach the surface and be applied to the diseased member. In the other instances the material composing the device may be saturated before or after compression, or the gelatinous covering may constitute the medicated medium.

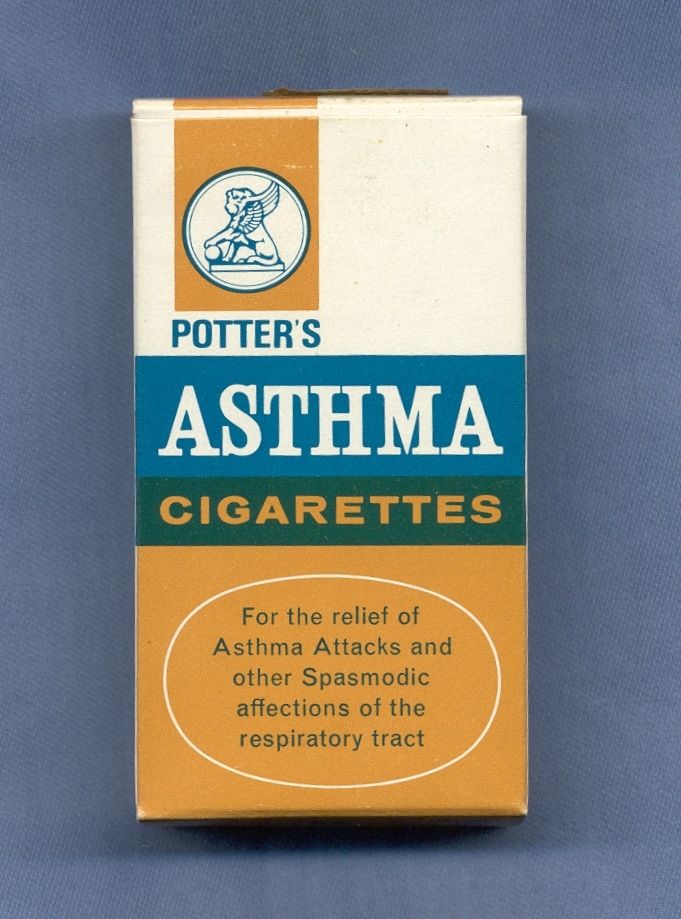

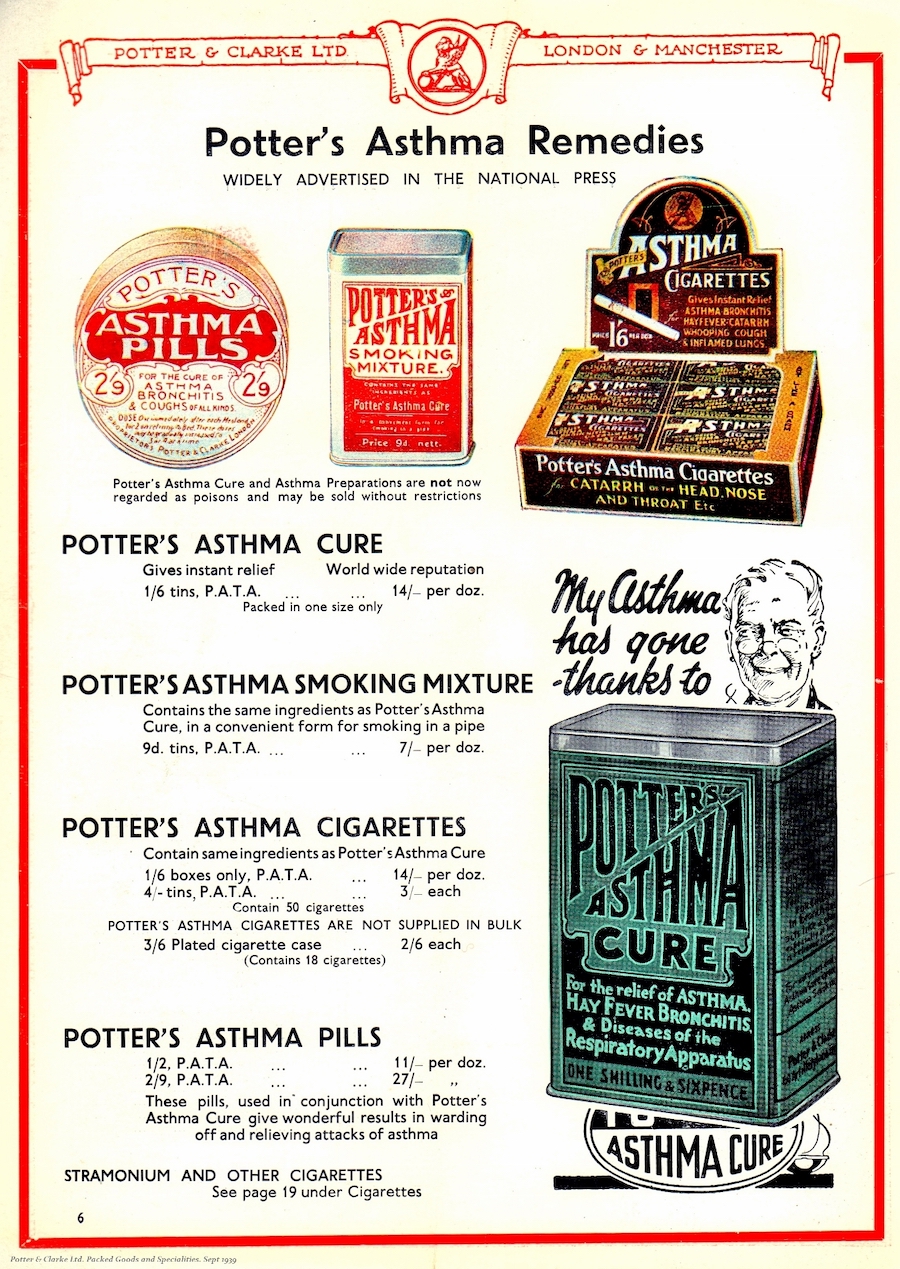

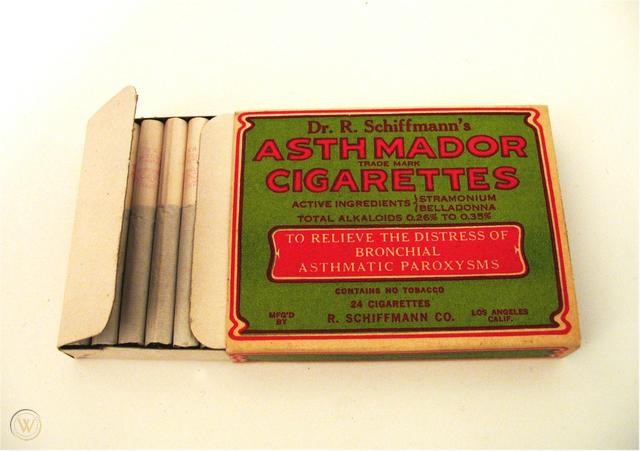

Asthma Cigarettes

““Exhaust the lungs of air, then fill the mouth with smoke and take a deep breath, drawing the smoke down into the lungs. Hold a few seconds, then exhale, through mouth and nostrils. Prescribed dosage 4 a day.” Not sound advice for someone with asthma, surely?

Well, it’s actually not as crazy as it sounds. Here us out: smoking to relieve what we now understand as “Asthma” is a practice that can be traced back thousands of years, when Ayurevedic medicine called for the smoking of a plant with atropine, Atropa belladonna, to heal throat and chest ailments. “The ancient Greeks,” says Gerald C. Smaldone in Drug Delivery to the Lung, even “sent consumptive patients to the pine forests of Libya to benefit from volatile gases released there.” Air was for inhaling – and infusing – to heal. For the most part, the asthmatic cigarettes that arose in the early 19th century, and declined in the 1950s, didn’t include tobacco.

But they did contain a cocktail of herbs and narcotics that almost always included atropine, which diluted the airways of the lungs to temporarily relieve symptoms, while simultaneously rendering the smoker lightheaded, nausious, hallucinegic, and a victim to a rapid heart-rate increase. Regardless, Potter’s Asthma Cigarettes, Himrod’s Cure for Asthma, Dr. Kellogg’s Asthma Remedy – you name it – soared in popularity…

It was the great French writer Marcel Proust, an asthmatic, who left the world perhaps the most vivid description of what smoking the little buggers did to one’s body. “‘Misery of miseries or mystery of mysteries…” he wrote his mother about smoking during an attack, “That [applies] very well to me at the moment. [My asthma] obliged me to walk all doubled up and light anti-asthma cigarettes at every tobacconist’s I passed. And what’s worse, I haven’t been able to go to bed till midnight, after endless fumigations…”

Unfortunately for Proust, it wouldn’t be until the latter half of the 21st century that the dangers of smoking became clearer, and doctors stopped slapping their names on both tobacco, and asthmatic cigarettes alike.

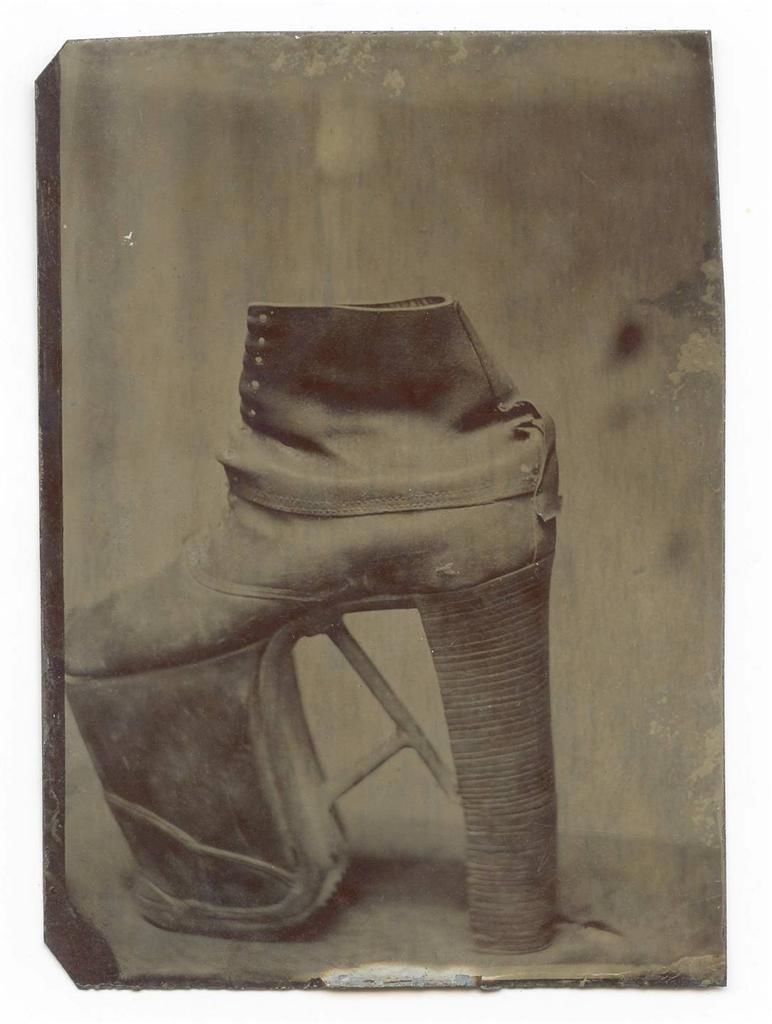

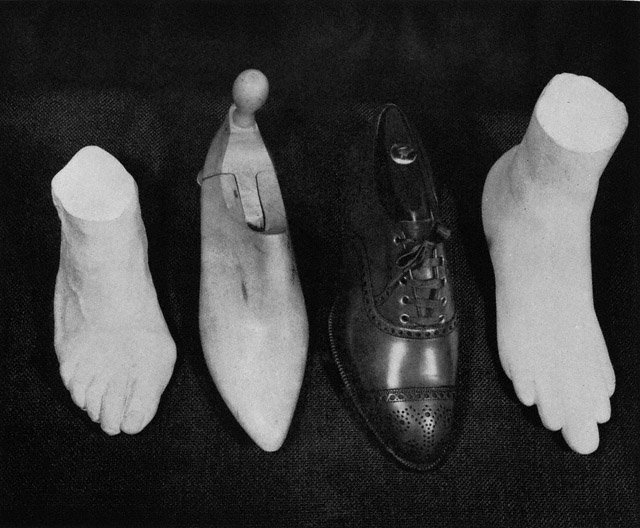

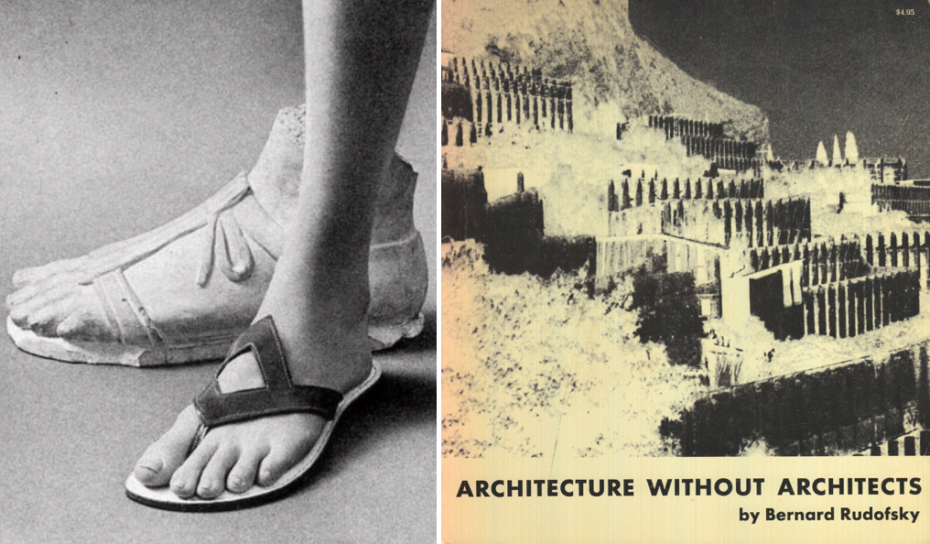

Sky-High Orthopaedic Shoes

For as long as humans walked this good green Earth, we’ve had foot problems. In the late 1800s, companies began introducing relatively affordable “corrective” footwear that aimed not only give a woman some height in her heavy dress, but to fix her woman’s posture, and, in some cases, totally reshape her foot. Up until the 1940s, the Federal Trade Commission didn’t crack down on companies that used language like “Scientifically recommended…” or “Doctor’s best heels!” which meant that all the strains imposed on a body in sky scraping heels could be written off as mere growing pains to better health. In fact, the entire evolution of heels is rather fascinating. Luckily, the wearing of such kicks today is not doctor un-recommended (unless you’re Lady Gaga).

It wasn’t until the post-war years that Western cultures really started embracing the whole “free the foot” concept, notably through architect and shoe designer Bernard Rudofsky, whose 1944 book Are Clothes Modern? made a case for more uninhibited shoe forms long before anyone else. Except maybe the Greeks.

Rudofsky’s footwear designs were like his houses: spartan, and engaged with nature. His brain in general was a goldmine of quirky shower thoughts, like, why the American-style toilet is “effectively a septic humidifier, and why American-style bathtubs are impossible for adults to lie down in, and are as a matter of routine permanently fixed two or three feet away from a septic humidifier.” But we digress.

Rudofksy was on to something (his brand, Bernardo, is still going strong). A 2007 study led by the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa, confirmed that after studying the feet of about 180 humans from around the world, some alive (and some 2,000-years dead), the healthiest feet were the most barefoot.

Have a Wine & Cocaine Cocktail, they Said. It’ll be Fine they said.

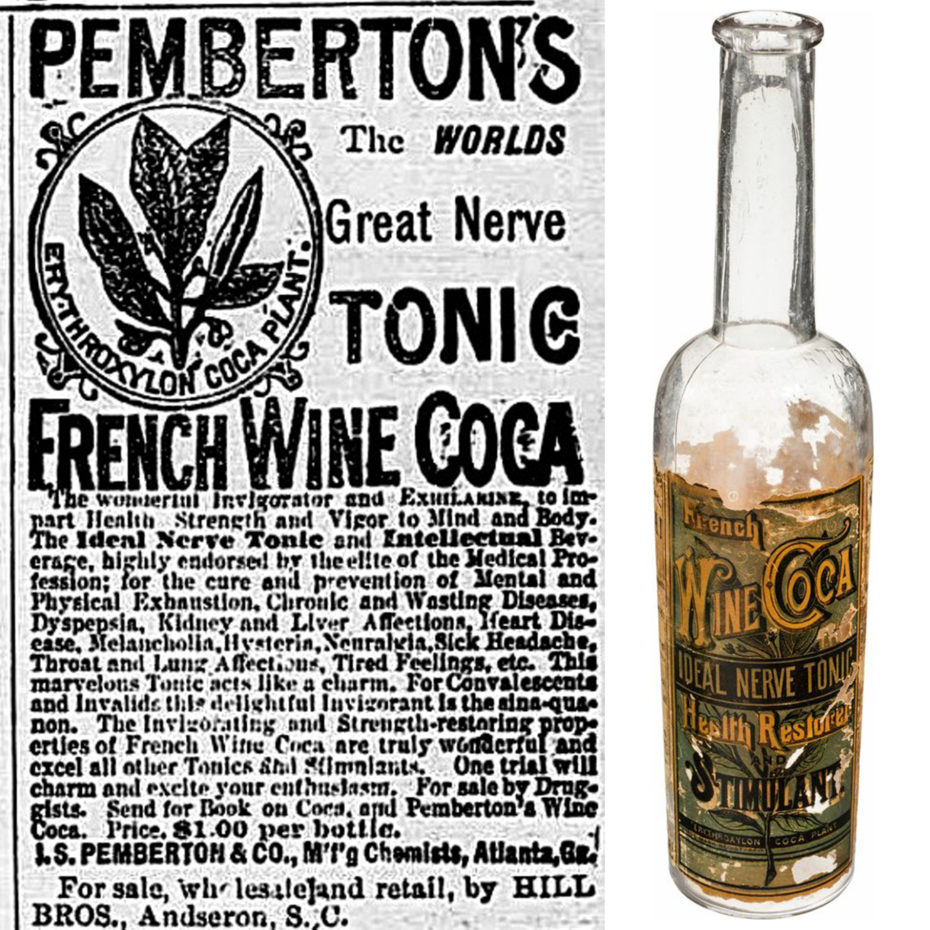

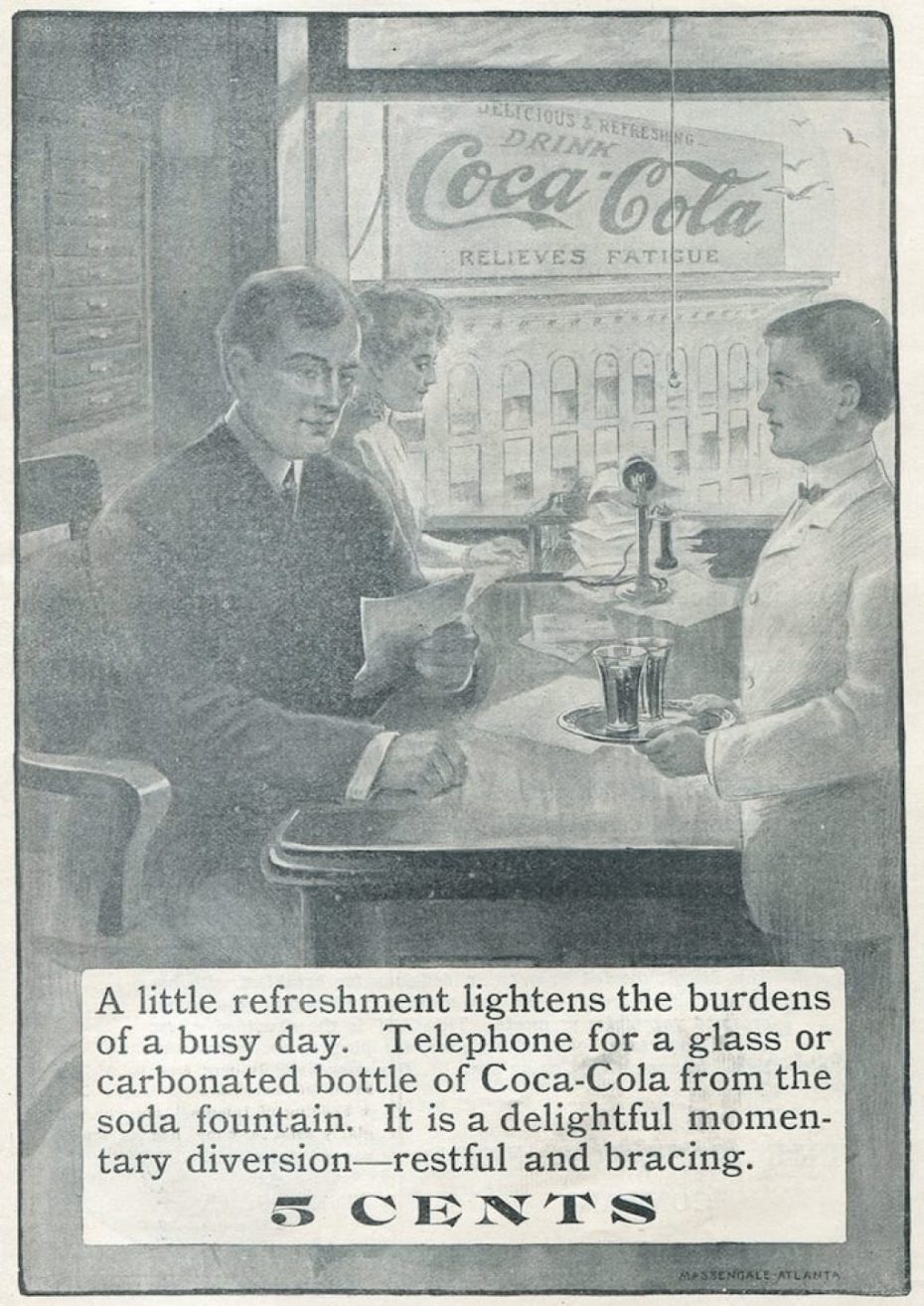

Coca-Cola’s name is telling enough when it comes to the company’s retired, cocaine-heavy recipe. But the roots of the soft drink go back even further (and get even weirder), taking us to French wine country in Bordeaux…

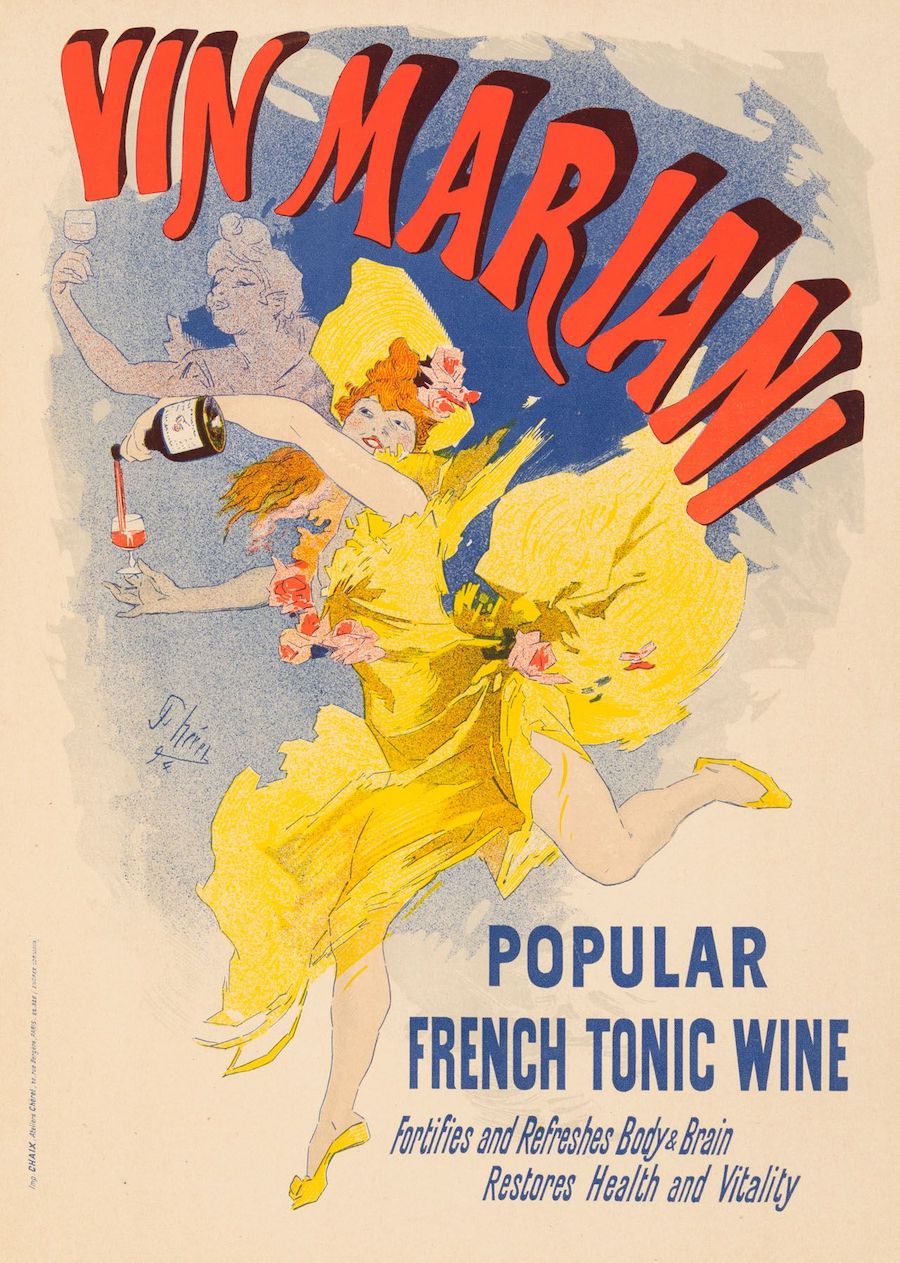

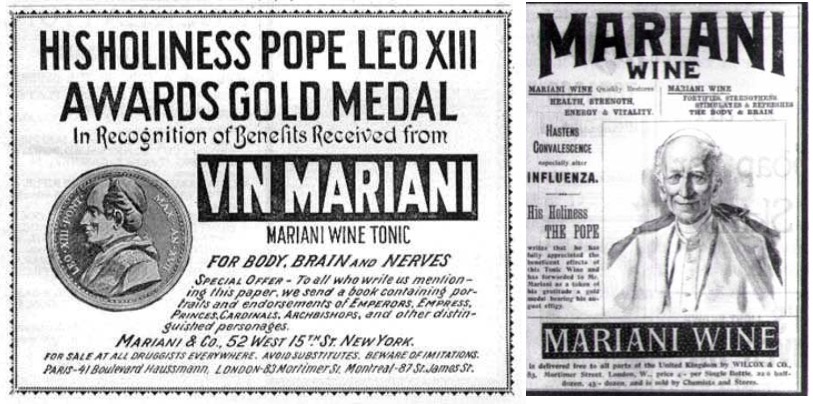

It fortifies and refreshes body and brain! It restores health and vitality! Or at least, that’s what folks thought. In 1863, this tasty blend of Peruvian Coa leaves, cola, and wine was cooked up a French-Corsican entrepreneur in Paris named Angelo Mariani. “Coca Wine” was a hit, with fans from every echelon of society. Jules Verne, Thomas Edison, and Sarah Bernhardt drank it – hell, even the Pope was a fan of its cure for melancholia…

With great success came great competition, and the arrival of “Pemberton’s French Wine Cola” on the American market. Invented by a Southern pharmacist named John Pemberton, the knock-off was a huge success until prohibition legislation came knocking, and he had no choice but to come up with a non-alcoholic version of the wine – renaming it, Coca Cola. Read about the whole deliciously sordid history here.

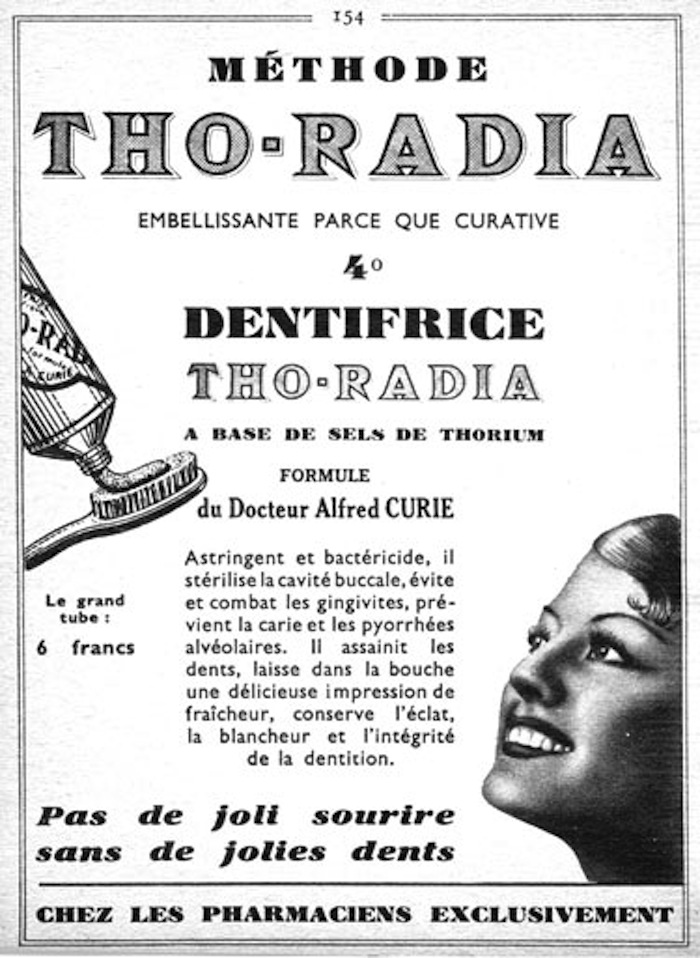

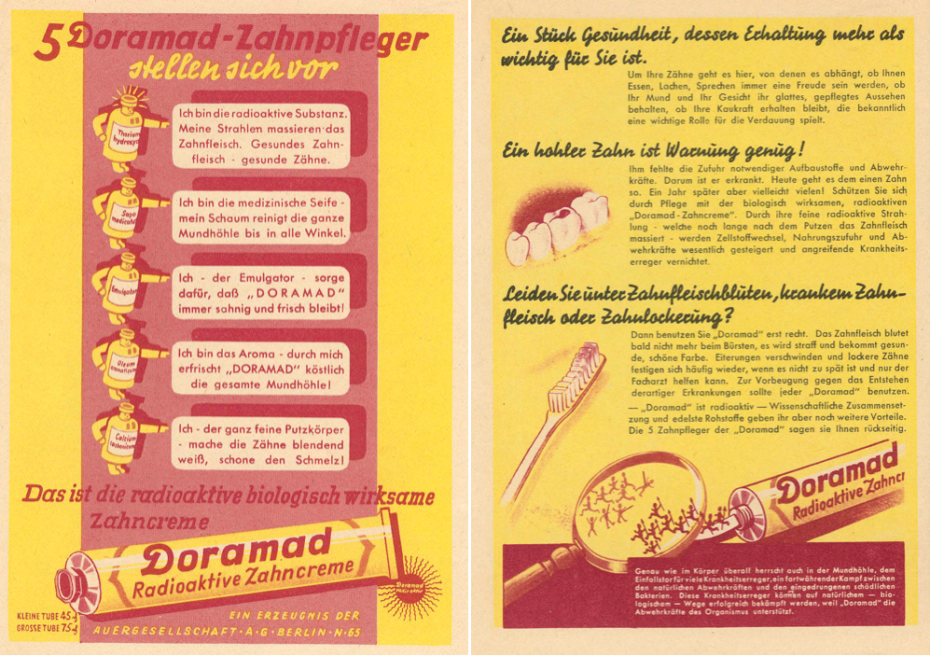

The Generation that Brushed their Teeth with Radioactive Toothpaste

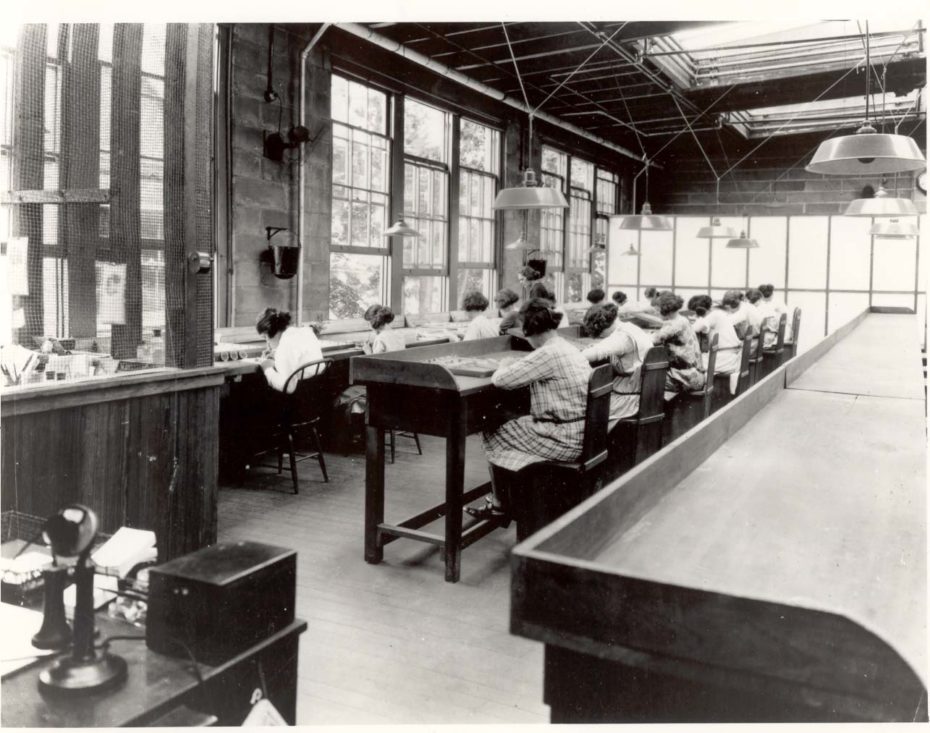

Our heart breaks for the “Radium Girls” – that group of New Jersey women who became the collective, tragic poster child for the dangers of radium poisoning in the early 20th century. The radioactive metal was common in manufacturing tasks that were done largely by such young gals, taking their first brave steps into the work force…

But if you stood over their graves today, the collective radiation levels would still cause the needles to jump on a Geiger counter. The women in the New Jersey factory above were specifically using radium to create cutting-edge, “glowing” watches for the army – but radium was everywhere, and marketed by companies (in Europe and America) as yet another cure-all for a (literally) glowing future. Radium was in watches, water, and makeup. It was even in toothpaste…

Radium was touted as a “truly remarkable” element, capable of “restoring vitality” and other vague medical benefits. In reality, it caused anemia, bone fractures, necrosis of the jaw, and an ultimately grisly death. What’s more, the factory’s management was far from ignorant to these realities while they encouraged the women not only to lick their radium-dipped paintbrushes (to keep that fine painting point), but to consume radium in every way shape or form in their lives. The fallout was disastrous: one nasty court case against the factory, and the untimely death of so many women.

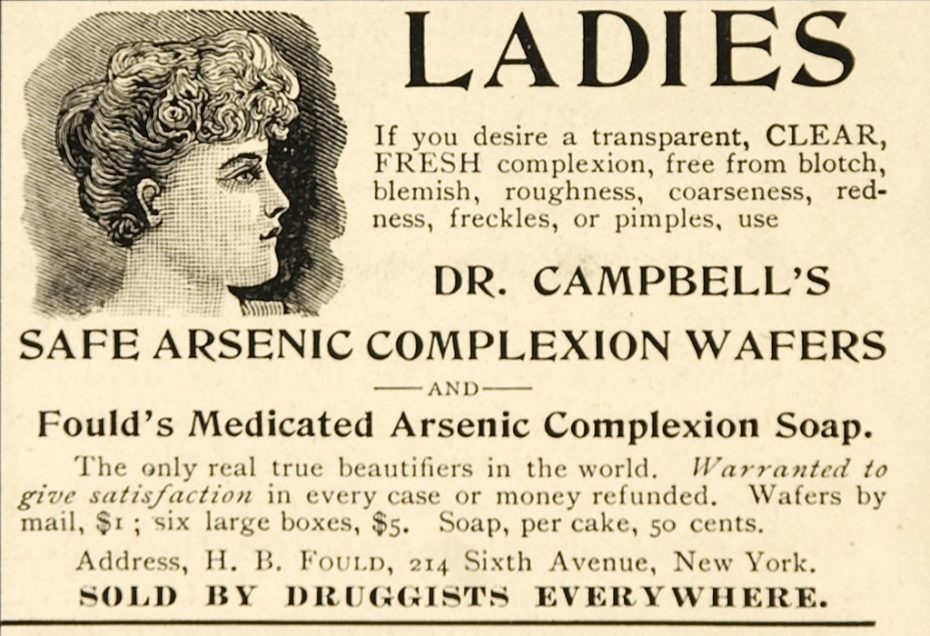

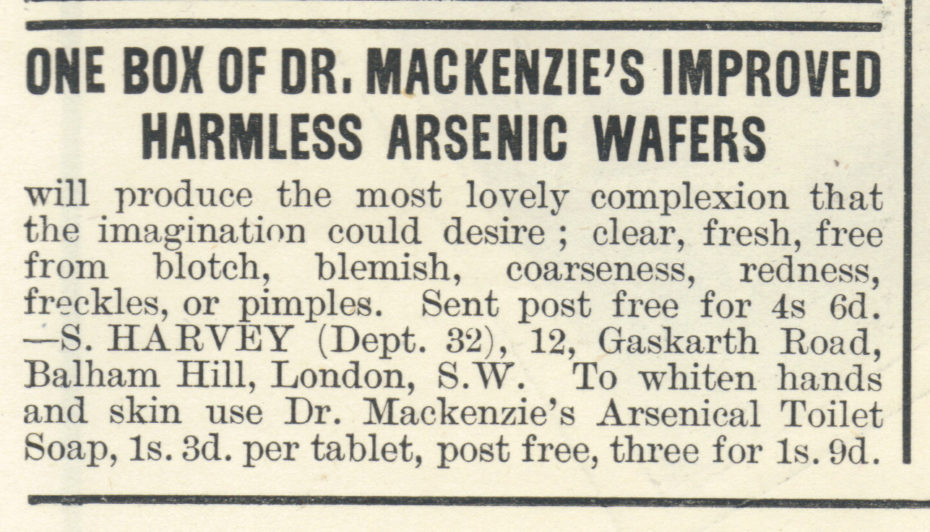

Arsenic Soap

The word “arsenic” today is synonymous with Agatha Christie-esque murder, but it was once the go-to for trendy women in the 19th century. The reigning Pre-Raphaelite aesthetes were smitten with the chemical’s gauzy, green glow – called “Scheele’s Green” or “Paris Green” – and it was added to medicines, food, and even textiles and beauty products. Dr. Campbell’s Soaps, for example, were sold as “the only true beautifiers in the world,” capable of clearing out blotches, blemishes, pimples and such for a “fresh complexion” with its quality ingredients. And roughly two grains of arsenic…

“Arsenic is consumed for two purposes,” writes one 1856 journal, The Chemistry of Life, “First, to give plumpness to the figure, cleanness and softness to the skin […] second, to improve the breathing and give longness of wind, so that steep and continuous heights may be climbed without difficulty and exhaustion of breath.” Eventually, arsenic’s true after-effects (death) rung in 1951’s “Arsenic Act,” which made restrictions on selling it tougher.

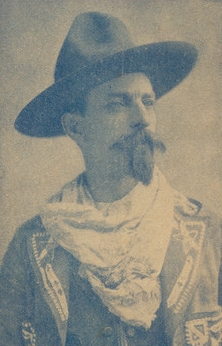

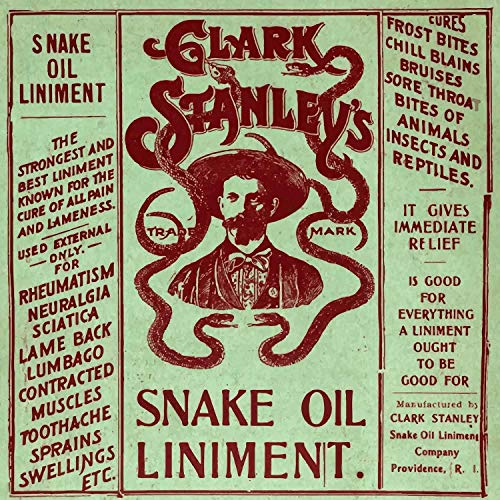

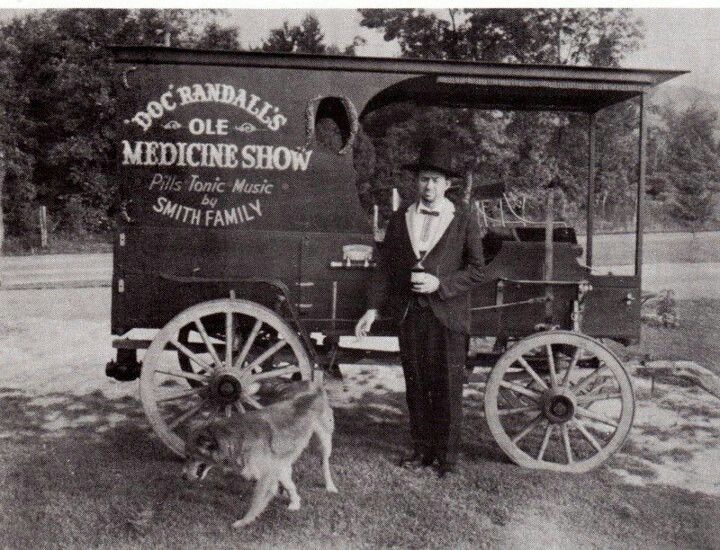

Clark Stanley’s Snake Oil

Clark Stanley was born at the end of Texas’ Chisholm Trail, grew up a cowboy, and fulfilled his self-made destiny as the South’s “Rattle-Snake King” by weaving an elaborate lie rooted in the very real, ancient tradition of medicinal snake oil. For hundreds of years in China, the fat of water snakes that feed on Omega-3-rich fish were used to make oils that alleviated inflammation. There have contemporary studies that show the positive effects of real snake oil on test subjects – but Stanley’s patented oil wasn’t the real stuff. It was pure fiction.

Stanley was a lot of things – thrifty, wild – but he was an especially goof storyteller. He spun an elaborate tale about how he’d learned the secrets of Hopi medicine in Walpi, Arizona, when he was working as a cowboy there for over a decade. Soon, production facilities for his trademarked “snake oil” product popped up in Massachusetts and Rhode Island (the druggist he worked with was from Boston), and he’d go down in history as the epitome of the late 19th century, traveling medical conman…

In 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act came down on medical quacks like Stanley, who as it turns out, was filling his snake oil with nothing more than fats, mineral oil, turpentine, and a dash of red pepper. (Talk about a snake.) Amazingly, he was only fined $20 (the equivalent of $3,000 today) by the government when the the truth came out. Today, his nefarious legacy lives on through the derogatory term “snake oil salesman” – aka, conman.

Victorian Toilet Masks

Open your pores, hydrate your skin, and awaken your inner Hannibal Lecter with Madame Rowley’s Face Mask (or “Face Glove”). Created in 1875, this baby was the terrifying precursor of today’s face masks. Except that, instead of leaving it on for 15 minutes, women were meant to sleep all night in the rubber mask to sweat out their impurities, and fill the mask with bleach and other harmful chemicals to “treat” problem skin. Yikes.