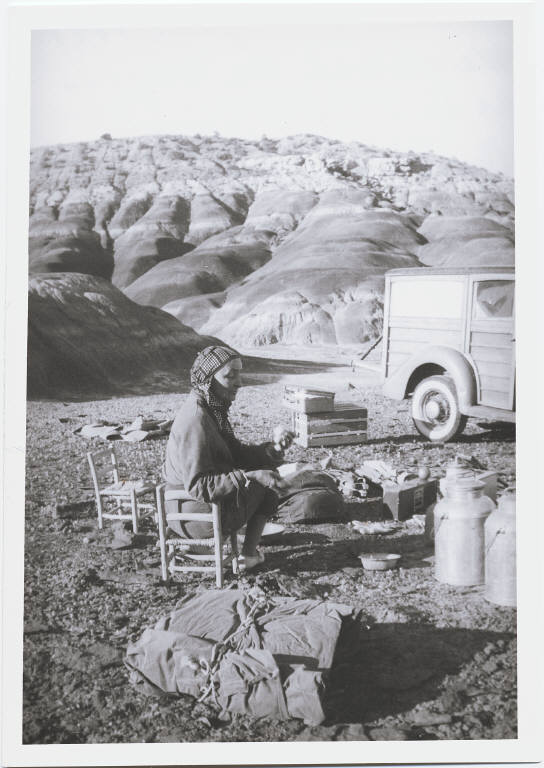

In 1934, Georgia O’Keeffe gutted the passenger seats from her A-Model Ford. It was time to make way for the only companion she needed, and wanted, out west: her art. There, in the dry heat of New Mexico, the pioneering female artist drove, hiked, and schlepped her canvases to the farthest corners of its blackened moonscapes and red dusted rocks. It was how she made love back to the landscape that had enchanted her and which seemed, for the first time, to be a place on the same wavelength of her own staunch character. It was home. Today, we’re retracing the New Mexico of O’Keeffe’s creative, independent spirit – and taking notes to inspire ourselves. Think Spartan home décor, and skulls. Dust. Naked sunbaths. An infinite sky. If you’re itching for the same energy this summer, you’re in luck – a lot of O’Keeffe’s legacy is not only visitable, but rent-able out west. Giddy up.

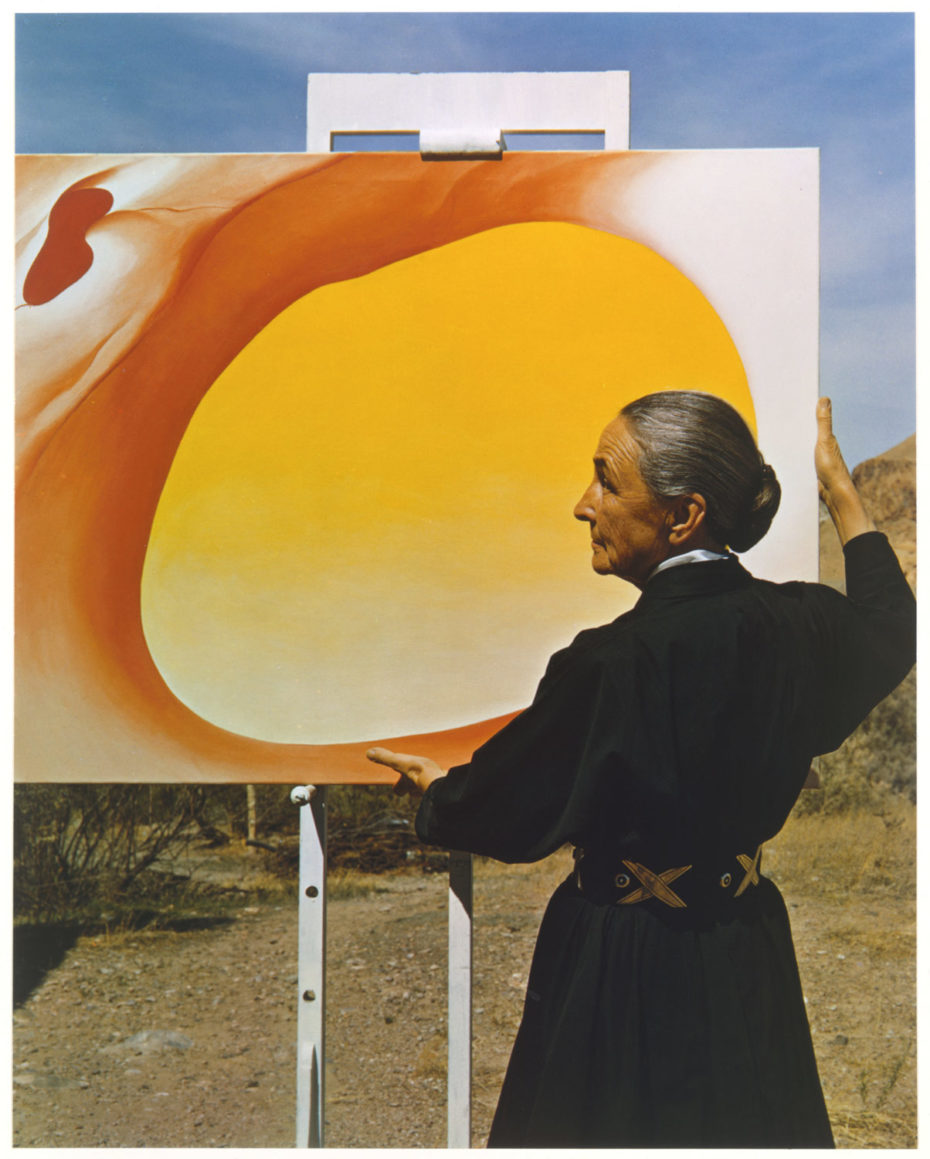

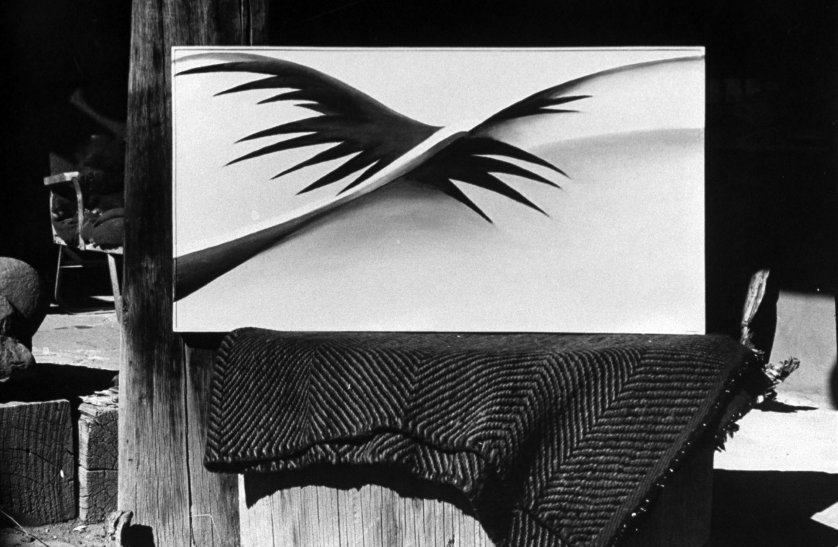

If you’re new to O’Keeffe, you may recognise her sensual poppies, irises, and lilies. You may know her bold interpretation of Americana, “Cow’s Skull: Red, White, and Blue,” or her sweeping skies. She became known as the “Mother of American Modernism,” exercising her already out-there philosophy (paint what you see, but as you feel it) with deft, abstract brushstrokes. “Nothing is less real than realism,” she said, “Details are confusing. It is only by selection, by elimination, by emphasis, that we can get at the real meaning of things.” No one else had her eye for what we’ll just call the vegetal architecture – better yet, anatomy – of a plant or landscape’s sensuality. No one else had that velvet touch:

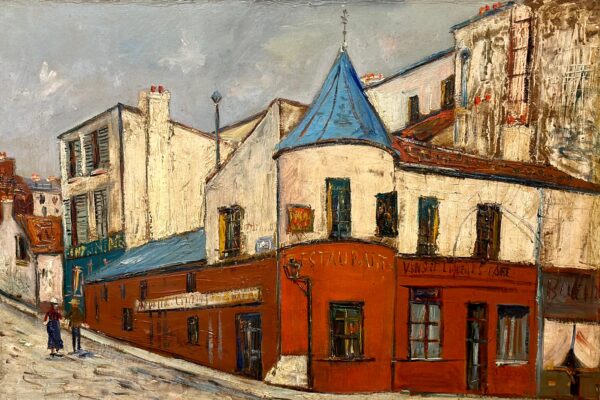

“Finally! A woman on paper!” declared the gallerist (and O’Keeffe’s future-husband) Alfred Stieglitz when he saw her early work in 1916. A man who followed his gut, Stieglitz decided to give her a show at his prestigious gallery, “291”, in New York City (no mean feat: it first brought Picasso and the European avant-garde to America) unbeknownst to O’Keeffe herself.

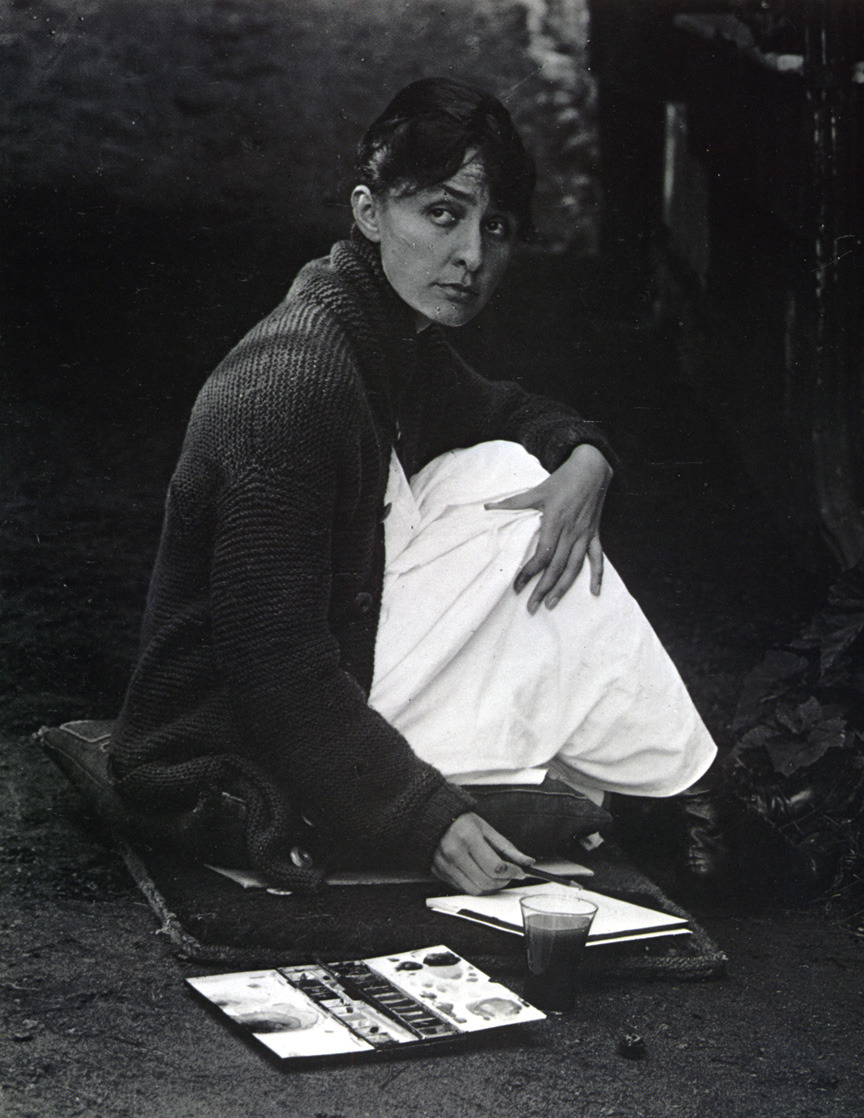

O’Keeffe was born in Wisconsin, studied at the Art Institute of Chicago, and weathered a lot of patriarchal BS. Most famously, when fellow painting student Eugene Speicher told her, “I’m going to be a great painter, and you will probably end up teaching painting in some girl’s school.” He was both right, and tremendously wrong: O’Keeffe did end up teaching in Texas as a fine arts teacher. Then her friend and former classmate, Anita Pollitzer, showed her work to Stieglitz and boom – she’d found her fair shot in the fine arts arena.

The correspondence between O’Keeffe and Stieglitz, who was married and twenty-plus years her senior, blossomed into a great love. From 1915 to the year of his death in 1946, some 25,000 pieces of paper were sent between the two according to a 2011 NPR article.

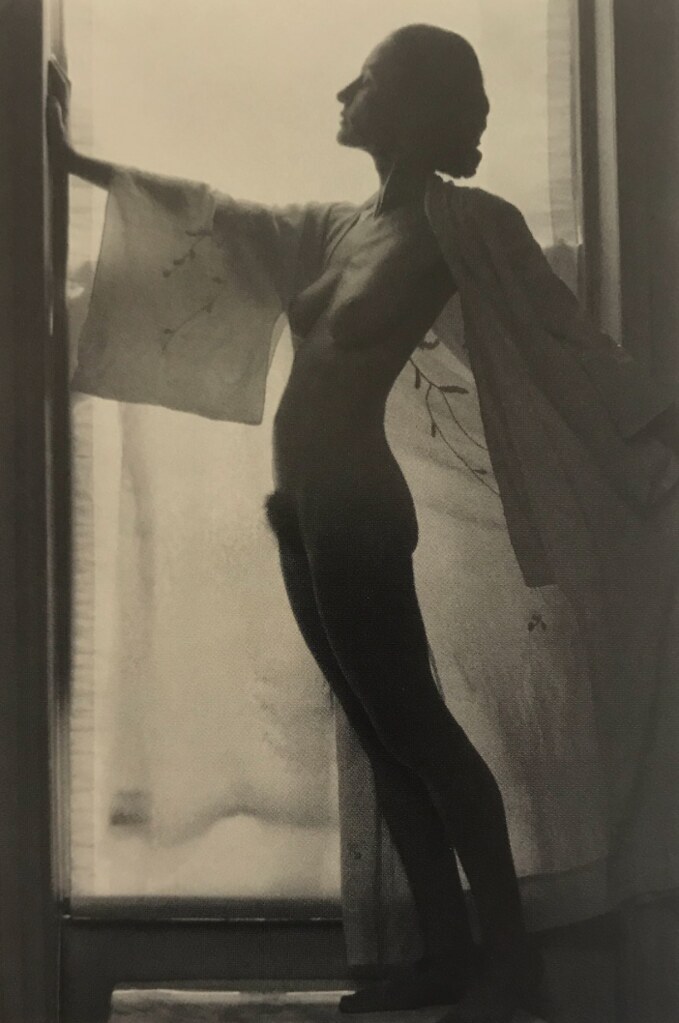

By 1924, they were not only married, but one another’s brightest muse-critics, living out the dream on the NYC art scene. Stieglitz himself was a talented photographer who took his work very seriously. “When I make a photograph,” he said, “I make love.”

But O’Keeffe liked being alone. A lot. In a 2017 BBC documentary on her life, O’Keeffe’s great-grand niece says that even growing up, “she would go off more by herself, [and] was happier by herself. She would play with this doll family under a tree…by herself.” Steiglitz, meanwhile, was Mr. Social Butterfly (with a big family to match). There was also mounting tension from their open marriage, and the fact that Stieglitz didn’t want any more children because he feared O’Keeffe would “lose focus” on her work. She split for the Southwest.

“When I got to New Mexico, that was mine,” O’Keeffe said, “As soon as I saw that, it was my country. I’d never seen anything like it before.” The summer of 1929 was the first of many extended stays in her newfound paradise. It didn’t hurt that she fell in with the eccentric Mabel Dodge Luhan, a society girl who became the Gertrude Stein of the Wild, Wild West.

She was a “salon hostess, art patroness, writer and self-appointed saviour of humanity,” her estate explains. “She was a woman of profound contradictions. She was generous. She was petty. Domineering and endearing.” In other words, anything but boring.

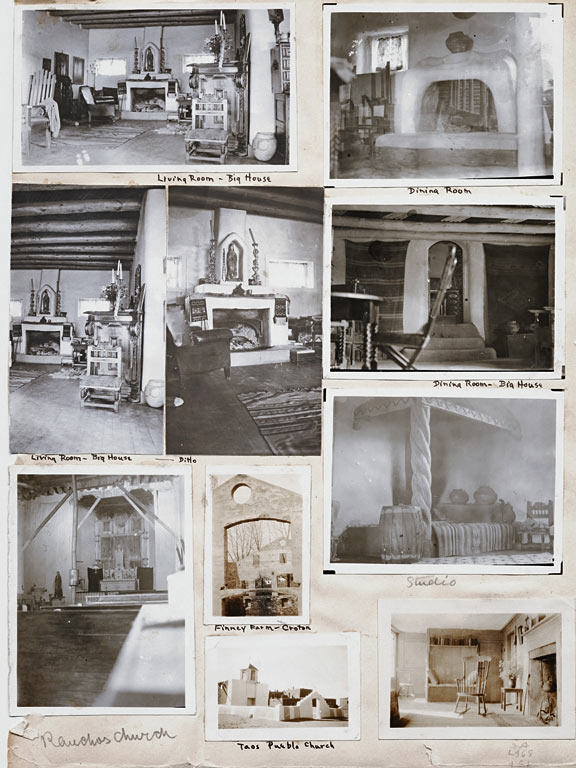

Mabel married a Native American painter, Tony Lujan, and lived in the closest thing one could have to a mini adobe castle in Taos, New Mexico. Everyone flocked to her home to take naked sunbaths on the roof, drink tequila, write, paint, and repeat. Igor Stravinsky, Martha Graham, and Carl Jung came. D.H. Lawrence painted the bathroom windows with kaleidoscopic designs. O’Keeffe loved it.

Luckily for us, you can not only visit the estate today but sleep in O’Keeffe’s room, or in Luhan’s hand-carved bed; book the solarium for a night, or shower amongst D.H. Lawrence’s artwork (and for less than half the price of a 5-star resort). Pretty epic:

O’Keeffe had already fallen in love with New Mexico, but she fell even harder when she visited Ghost Ranch in 1934. The massive parcel of land was owned by a concert pianist (and mega cowboy fan). O’Keeffe bought herself a slice, and never turned back.

She wrote a woebegone Stielgitz about how very happy she was to at last paint in nothingness, and that she would not be returning to New York – not because she resented him. New Mexico, she said, was just more thrilling (ouch). After all, this was pioneer country – and she really leaned into it.

LEFT: © Buffalogr / Flickr. RIGHT: © 2018 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/ Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

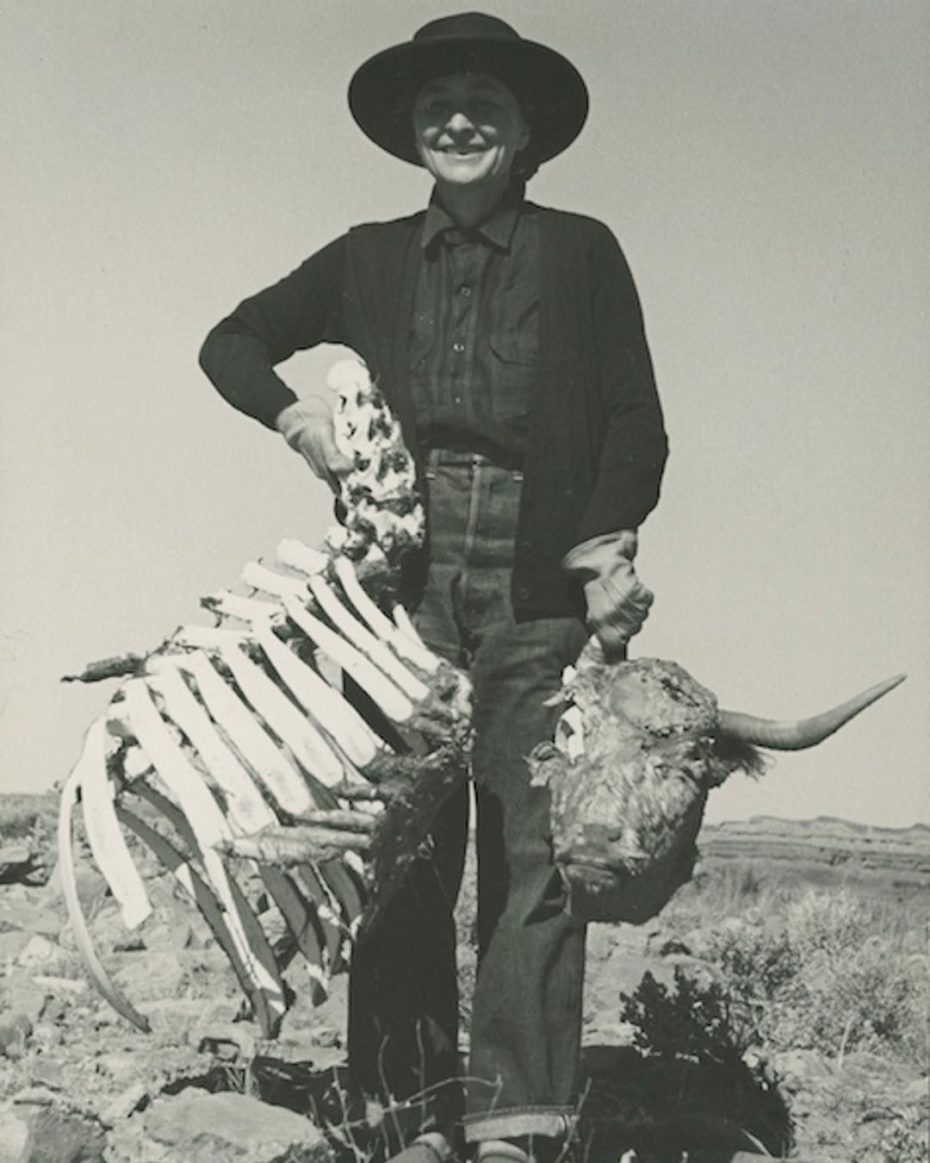

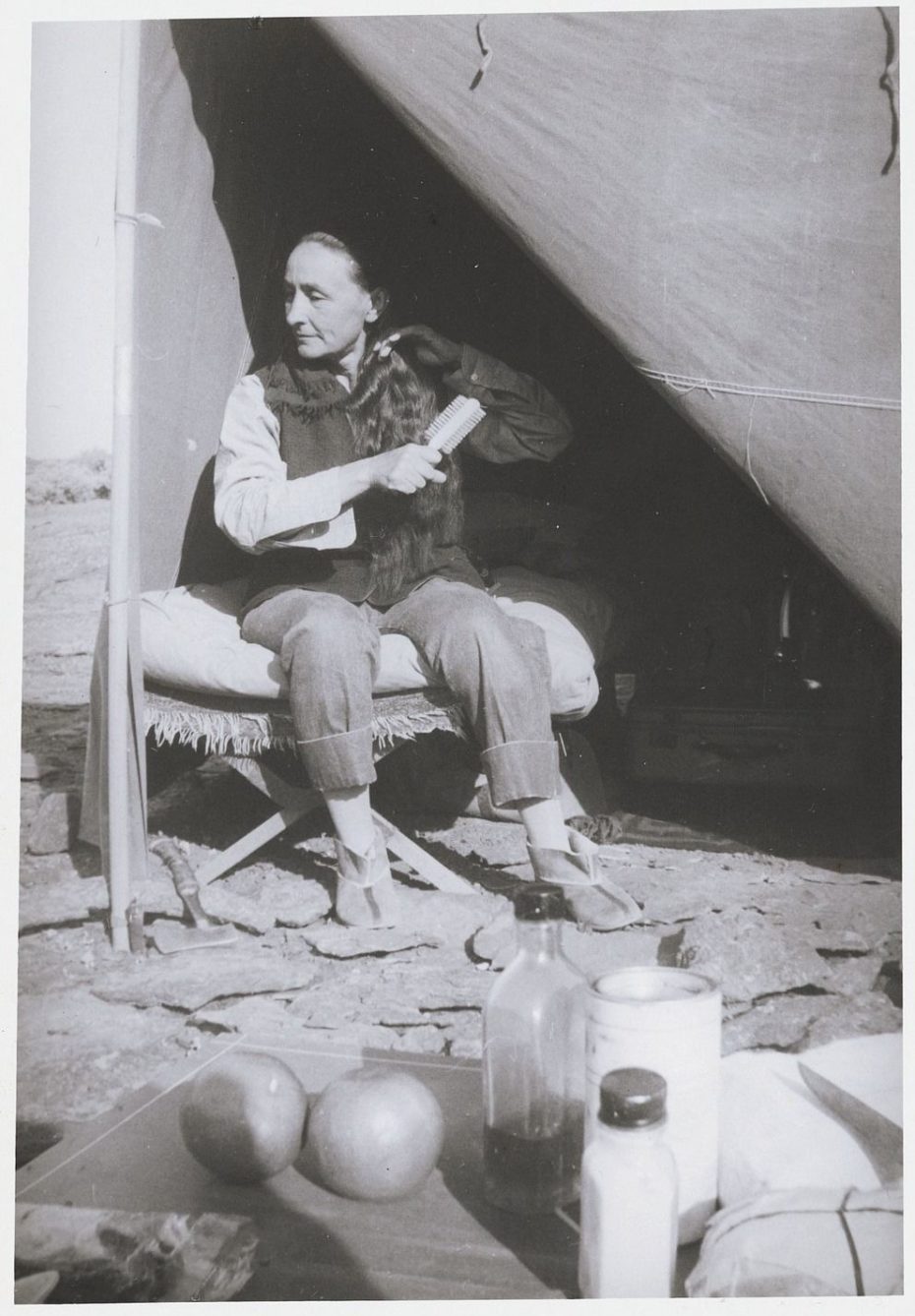

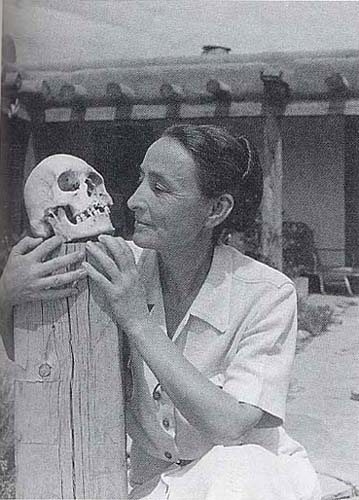

She kept the tails of rattlesnakes she killed in a tin box. She picked bones from the desert in lieu of flowers. “To me they are as beautiful as anything I know,” she said, “they are strangely more living than the animals walking around…the bones seem to cut sharply to the center of something that is keenly alive on the desert even though it is vast and empty and untouchable—and knows no kindness with all its beauty.”

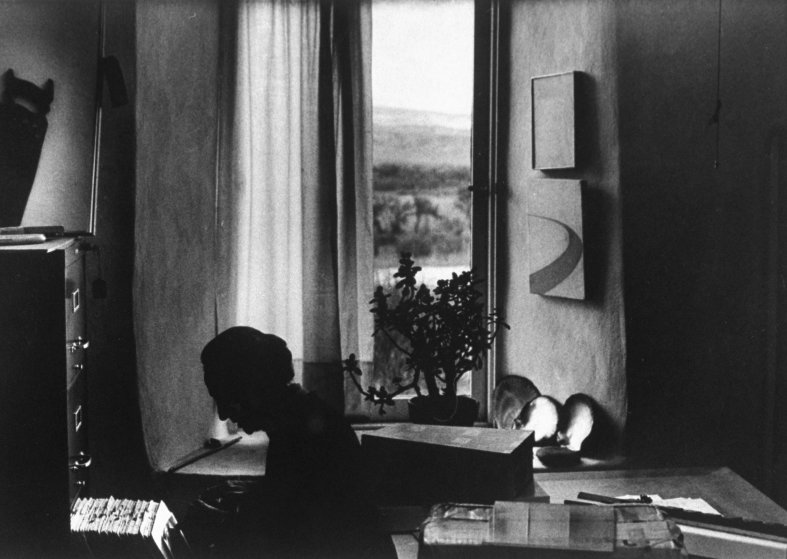

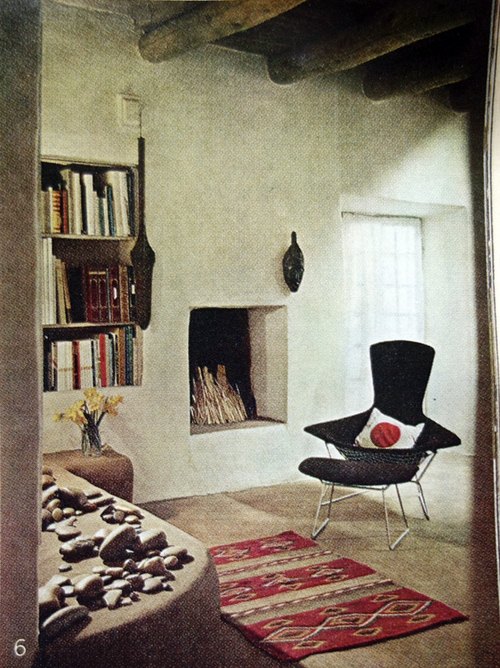

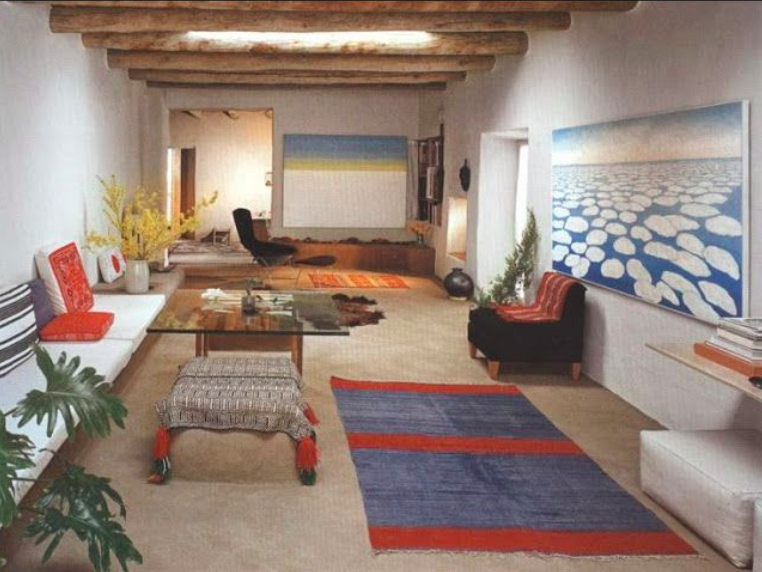

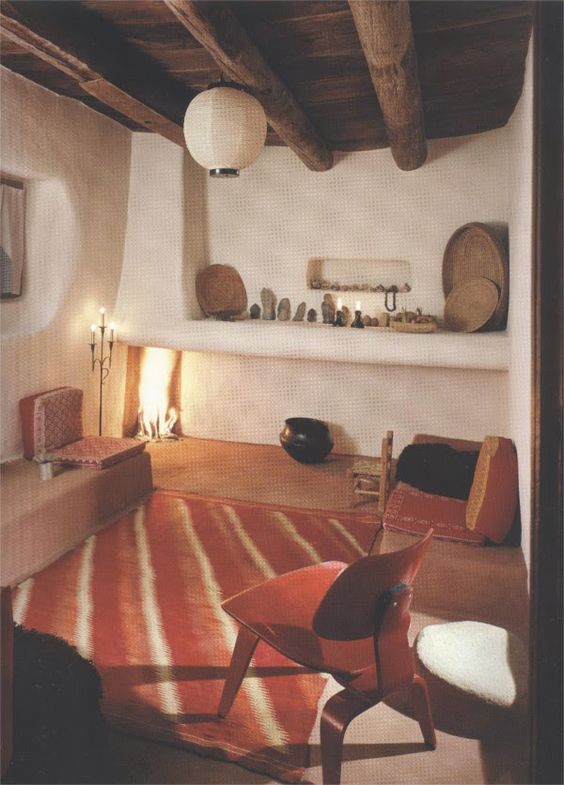

She was swept of her feet by its dust storms, delighted in becoming the colour of the dirt. She also cut an odd figure out West, wearing men’s clothes or else black, skull-hugging head wraps. You could spot her like an ant on the red horizon line, exposed and utterly, deliciously alone. Her home and studio was the same extension of that lifestyle:

Today, her home and studio is owned by Sante Fe’s “Georgia O’Keeffe Museum” and you can take both standard and behind-the-scenes tours of the joint. You can even “walk through the Black Patio Door – which inspired O’Keeffe to paint it many times – to enter the room behind, where she prepared her canvases, [and] go into the Fallout Shelter that O’Keeffe built on the property in the early 1960s.”

If you’re craving even more femme-empowering energy after that, check out the treat-yo-self retreats of the female-run organisation “Sol Maven” in Ghost Ranch. “[We] share a dream,” write the founders, “that all women be given the permission to take a pause from their hectic lives and the opportunity to reconnect with their most authentic self.” Bonus: they’ve also got the most adorable converted trailer-lounge (see above).

O’Keeffe lived to be nearly 100-years-old in her desert paradise, and if we take notes on her solitude, it’s not to call for a life of recluse for reclusion’s sake – to build an impenetrable spirit. O’Keeffe was none of those things. She absorbed all that was around her, and with joy. O’Keeffe is the embodiment of the epiphany it takes most of us a lifetime, or a lot of time, to have: that you are the person you’ve been looking for all along.

Reserve your guided tour of the Ghost Ranch house, your room at Mabel’s house, and your workshop at Sol Maven.