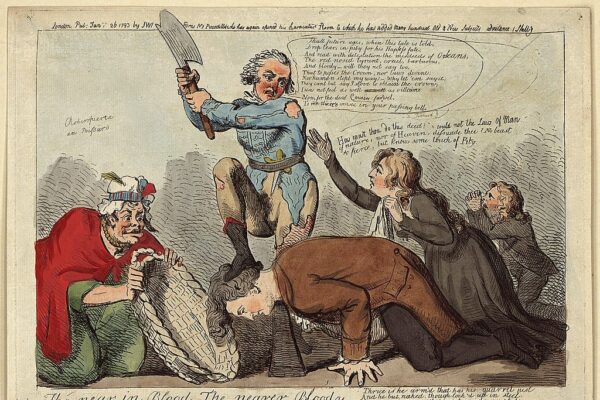

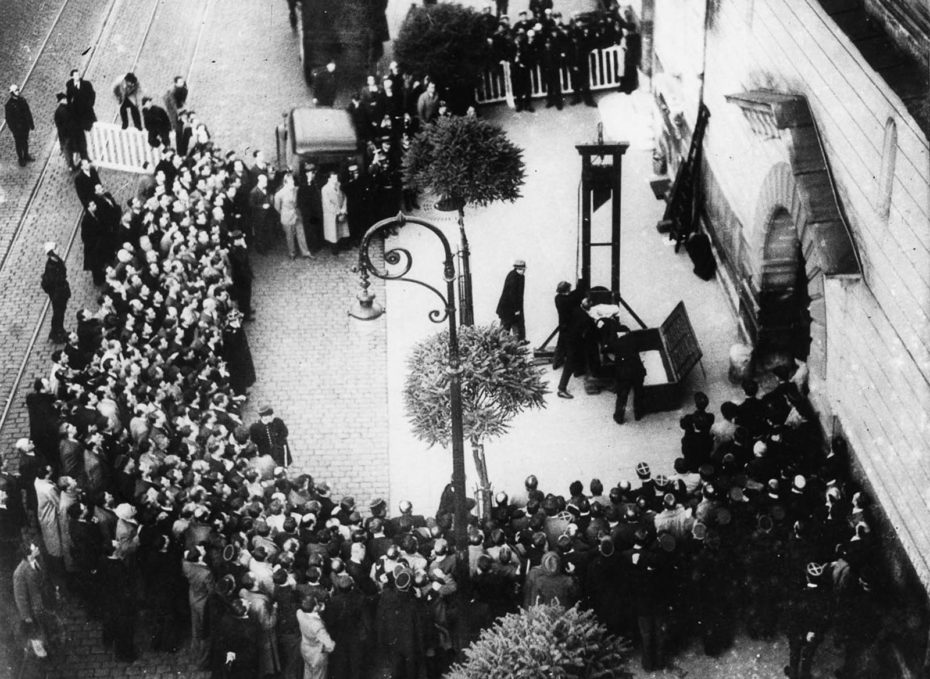

During the height of the French Revolution, France had just about lost its mind. The “Reign of Terror” was as terrible as it sounds. Rising revolutionary politicians like Maximilien Robespierre, were accusing everyone and their mother of treason against the new republic and some 16,500 people were killed by guillotine in a single year. The accusers would eventually become the accused, ending the Reign of Terror with the execution of Robespierre, and French society would begin to find its way back to normality. Sort of.

One of the most unusual stories to come out of post-revolutionary France must be the bals des victimes, or victim’s balls. Writings and records from the era suggest that an unusual subculture of society balls emerged as orphaned aristocrats began to see the return of their confiscated fortunes. The gatherings are thought to have been organised by relatives of guillotine victims, and only those who had lost a close relative to the guillotine, or narrowly escaped it, could be admitted to exclusive balls. The most coveted invitation in the late 1790’s Paris, France, came with its own set of manners and dress.

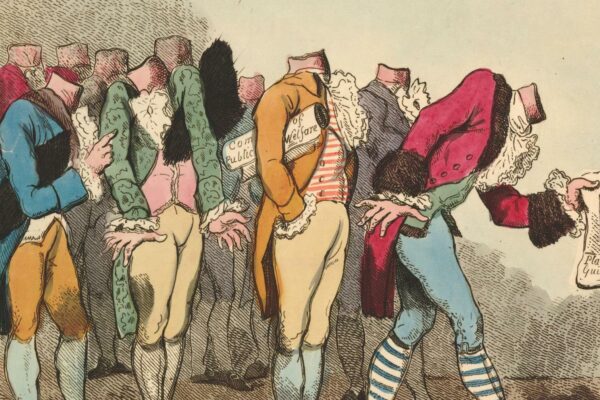

To enter, rather than a graceful bow to the host, guests allegedly saluted à la victime, by jerking their heads sharply downwards to imitate the moment of decapitation.

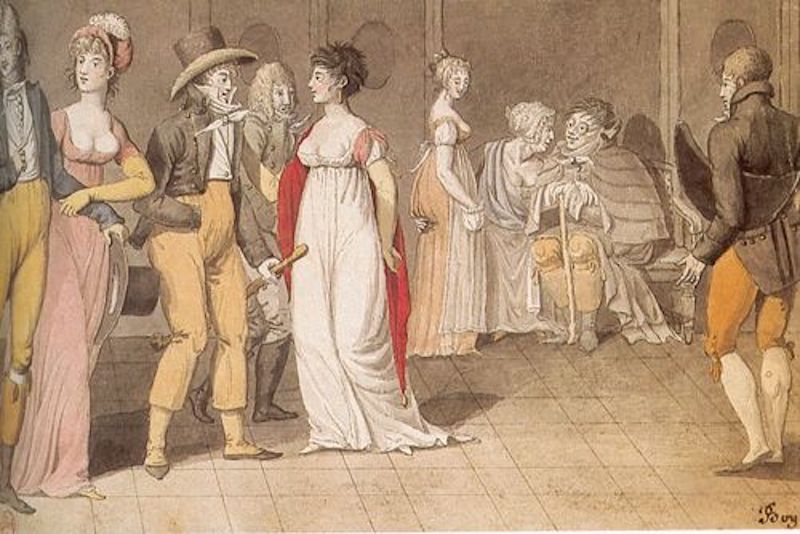

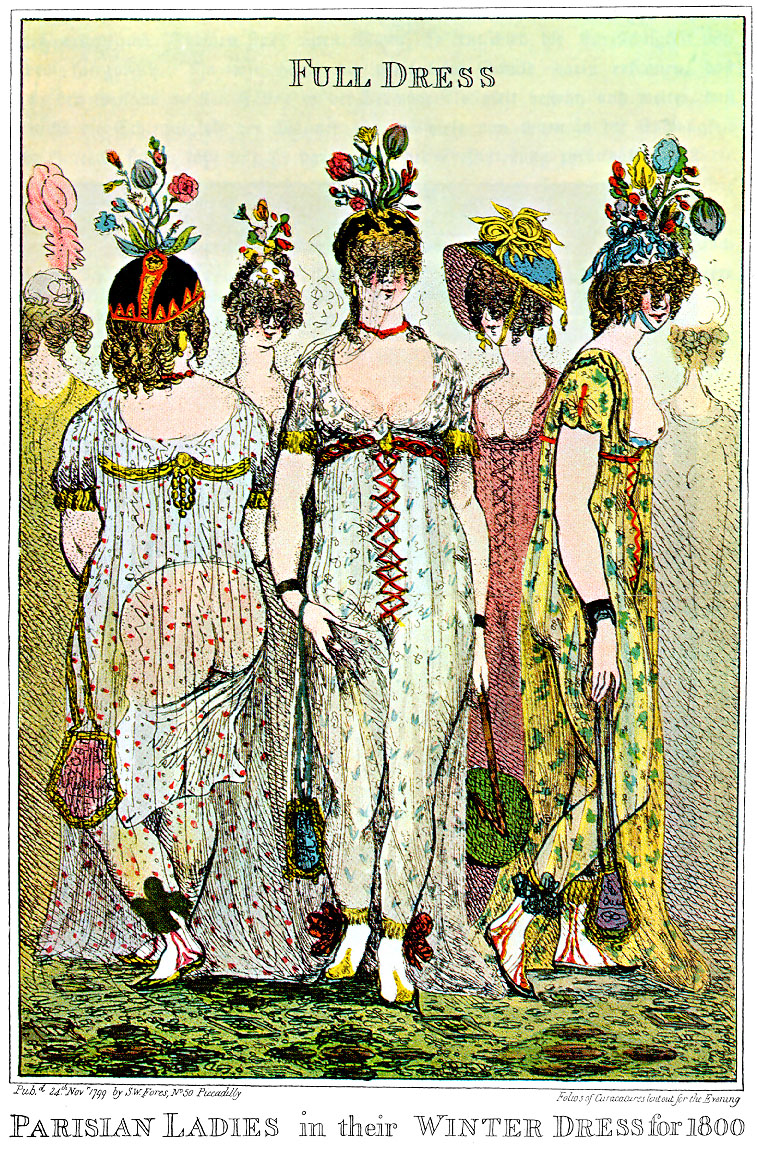

The dress code to these events were quite radical as well. It’s been recorded that women wore red chokers around their necks to symbolize where the blade would have severed the heads of their relatives from their body.

Women also began wearing red shawls over their thin nightgown-esque dresses that resembled the shirts of the prisoners. The red shawls are said to have been inspired by the shawl famously worn by Charlotte Corday as she climbed the steps to the guillotine for the murder of revolutionary Jean-Paul Marat while he was soaked in the bath.

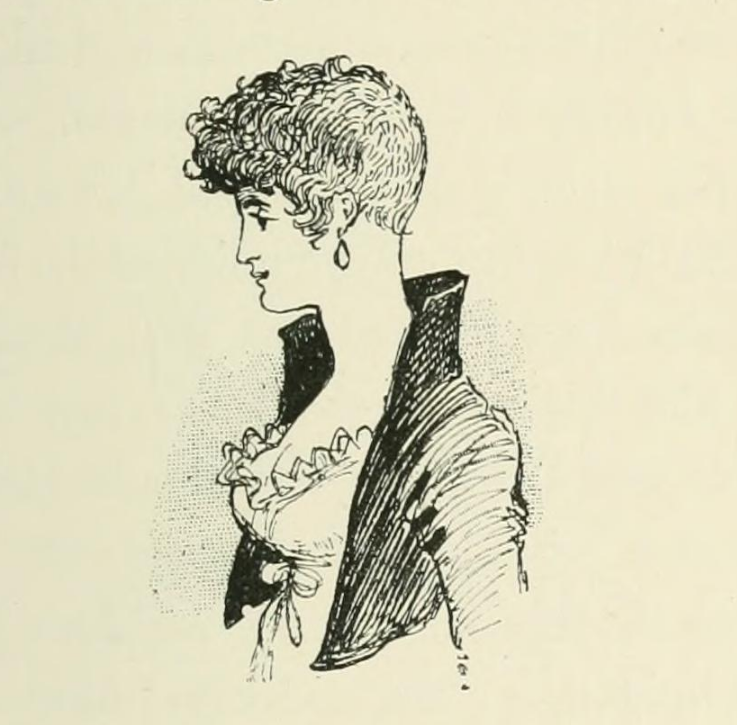

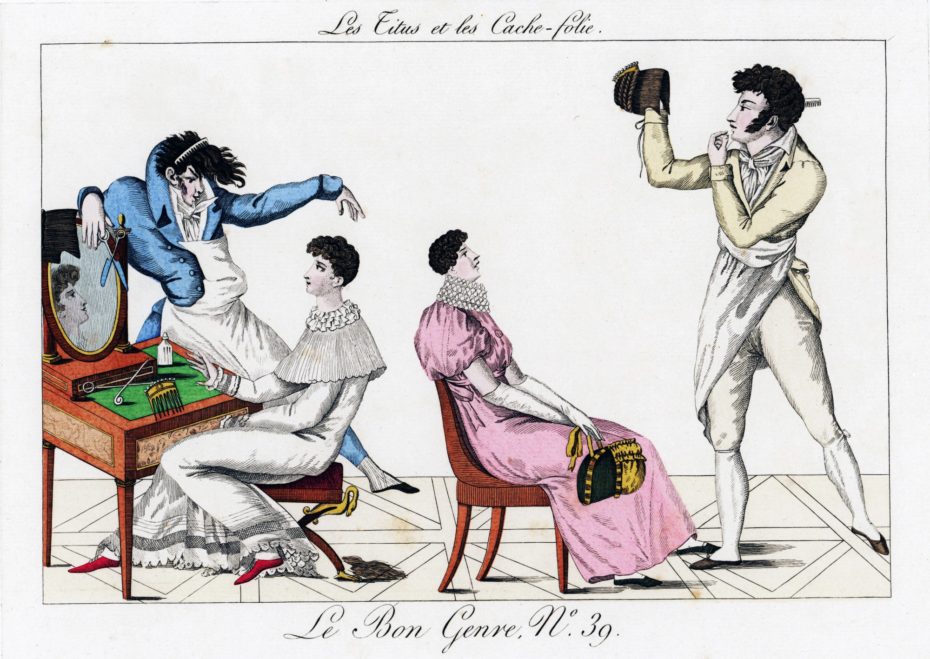

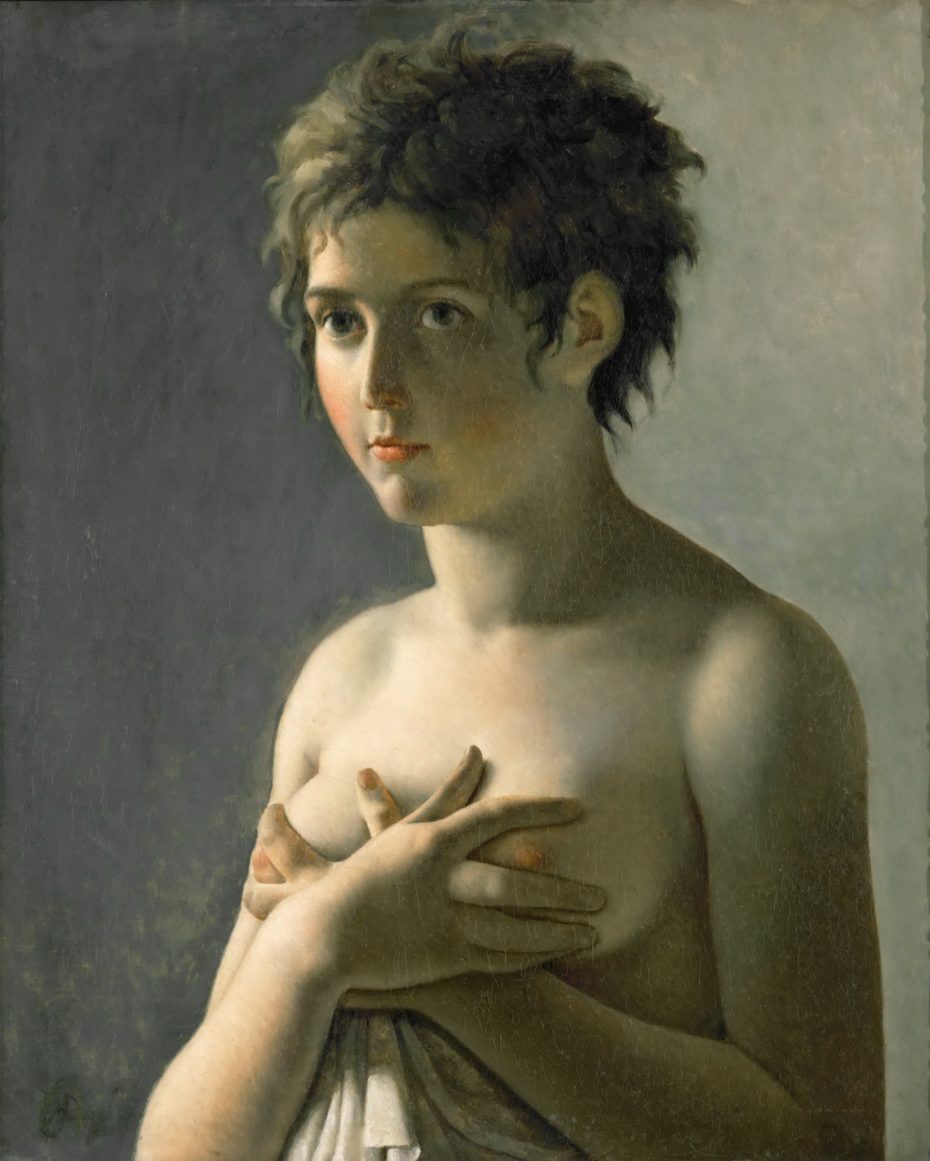

The balls are also believed to have helped bring about the trend for a new shorter hairstyle, aptly known as a coiffure a la victime, or à la Titus. It became fashionable amongst young women to opt for a drastic chop, baring their necks and mimicking prisoner appearances right before their deaths. When someone was to be beheaded, their hair was cut short so the blade could sever their head from the body with no interruptions.

If a woman preferred not to go for the full chop, she would attach her hair from the back over the skull, folding the tips of her hair almost over the eyes.

A far cry from the elaborate sky high wigs and basket-shaped skirts adopted by Marie Antoinette before the revolution, fashion post-Revolution was heavily influenced by the drama she and her fellow aristocrats endured. Bringing new meaning to the term, “fashion victim”, the trend was to literally dress like the victims of the revolution.

A fashionable aristocratic subculture in Paris known as the Incroyables and the Merveilleuses began appearing at society functions dressed rather scandalously in Greco-Roman dresses reminiscent of the undergarments their relatives had been stripped down to during their imprisonment.

Heels got the boot and some illustrations from the era depict women going out in public without shoes at all, possibly alluding to the victims that went barefoot to the guillotine. Their exaggerated style was likely cathartic for them, helping them reconnect with other survivors of the Reign of Terror, but also separate themselves from the “blood-drinkers” of the revolution.

France last executed someone by guillotine in 1977 and wasn’t officially abolished by the government until 1981.