Rosa Bonheur was one of the most popular artists of the 19th Century. Not only was her work being sold and seen around the world, songs were composed about her and dolls were made in her image. Today, some of Paris’ most thriving bars and nightclubs are named after her. But her artistic merit has been widely forgotten.

There are many schools of thought as to why this may be. A working theory is a classic case of history, historically, being written by men who were so incredulous that a woman could be successful enough to surpass their own achievements that they jealously erased her from records. Now, thanks to a dedicated few, Rosa Bonheur is being put back on the map, in more ways than one.

One hour south of Paris, the Château de Rosa Bonheur, in Thomery, was the artist’s home for the last 40 years of her life. It was purchased with the proceeds from a painting sold to the Metropolitan Museum in New York, Le Marché aux Chevaux (The Horse Fair) which is still on display to this day.

After decades of dormancy, new owner Katherine Brault has opened the house and studio to the public as a testament to the artist’s legacy – complete with a charming tearoom to welcome you into Rosa’s world.

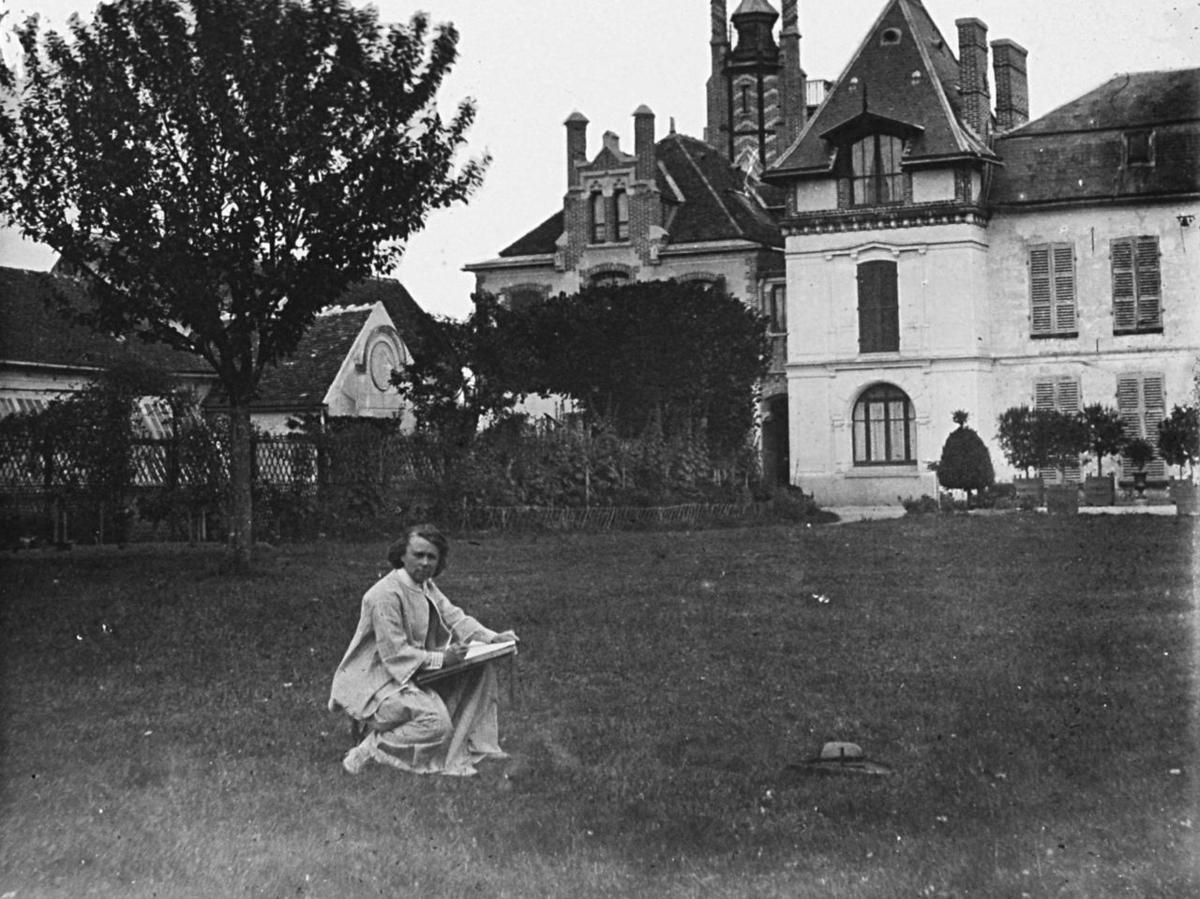

Rosa moved out to Fontainebleau forest in search of tranquillity away from the hubbub of humanity, to be among the wildlife that would define her practice. When she acquired the house in 1859, she had a large, light-filled studio built, where she continued to paint, sketch and sculpt right up until her death.

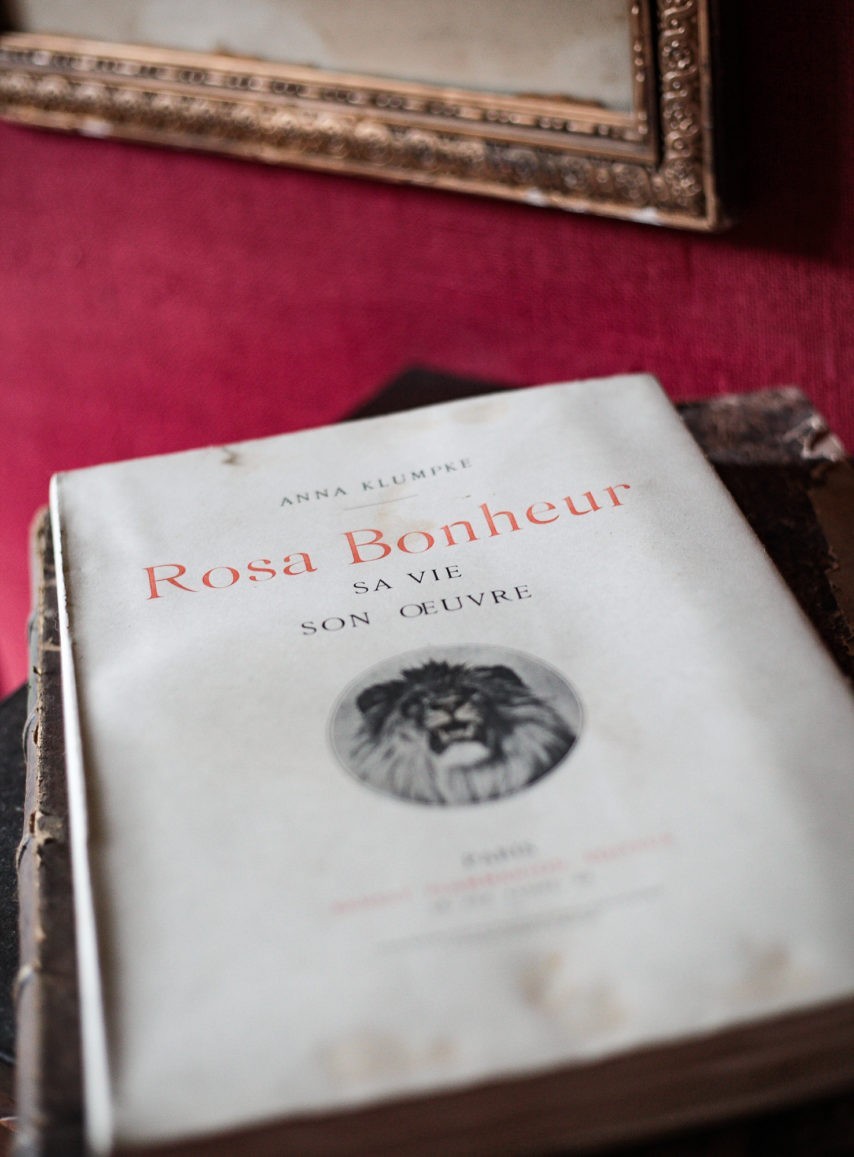

Today, the house remains largely untouched, save for a little dusting. In the study, the impressively practical pull-out typewriter on which the artist’s biography was written still surprises visitors. As does the bookshelf hidden behind a painting. In the study, a large canvass of galloping horses remains unfinished beside a palette of paints: a snapshot of her final moments, the last painting she would ever work on.

Her studio’s large collection of taxidermy is also surprising. Not so much the fact that it’s there – she was, after all, an animalier painter – but the fact that all of the stuffed animals were previously her pets.

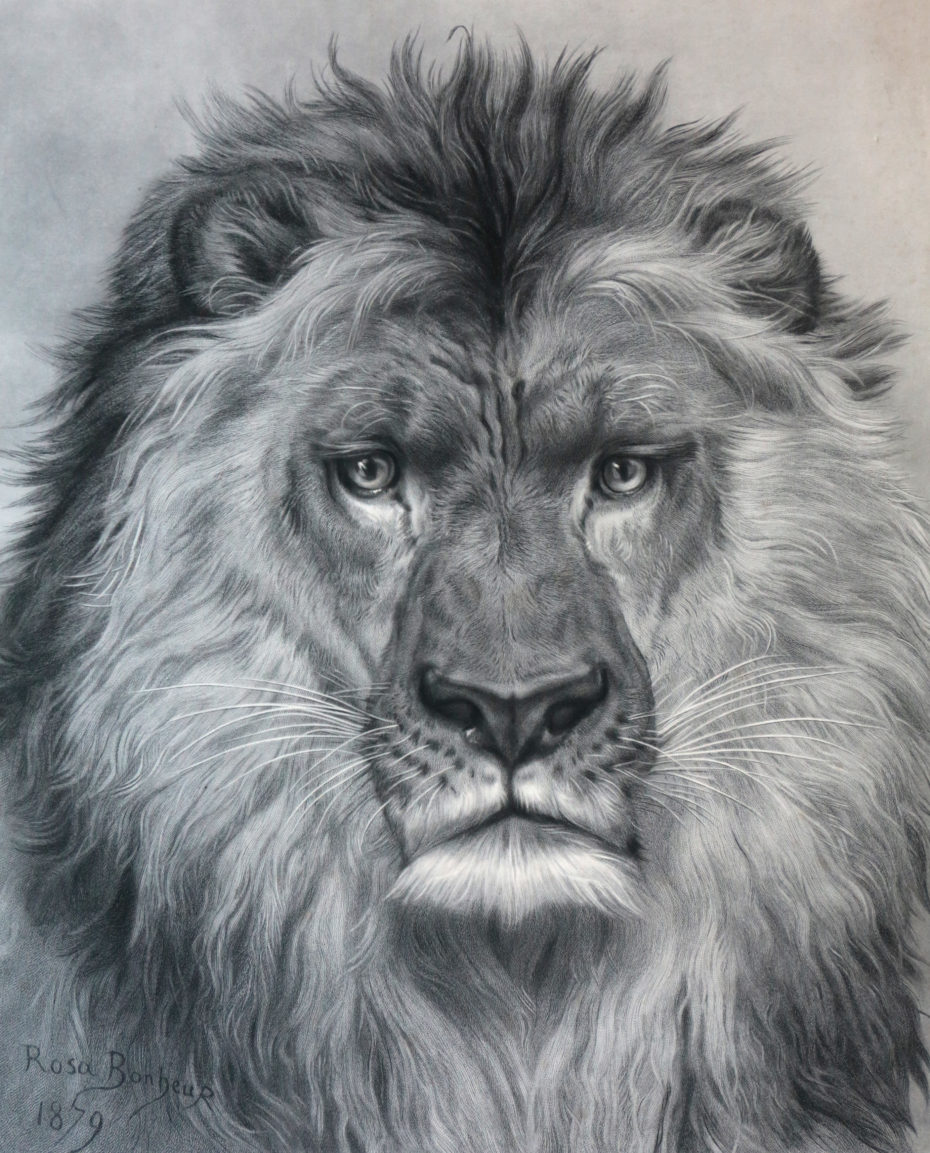

The house’s vast gardens allowed Rosa to keep over 200 animals on site throughout her lifetime, comprising over 45 species ranging from sheep and horses to not one, but three lions.

The menagerie on her grounds allowed her to study a diversity of individual animals up close to perfect her practice. Her work was characterised not only by her skill as a painter, but her approach to the subject: she wouldn’t just capture archetypal animals, she would paint unique portraits of a specific animal.

At the time, her views about animals were radical. She believed that they, like humans, had souls, and that the eyes were the window into these souls. As such, it is often the eyes of the animals in her paintings that draw you in.

Her mode of research was pretty out-there, too: in addition to her own grounds, she would venture alone into male-only spaces, such as livestock sales, farms and even the forest to observe her subjects. To do this, Rosa acquired a “permission de travestissement” – a cross-dressing permit – in order to blend in by wearing trousers which, remarkably, was still technically illegal for a woman to do in France until 2013.

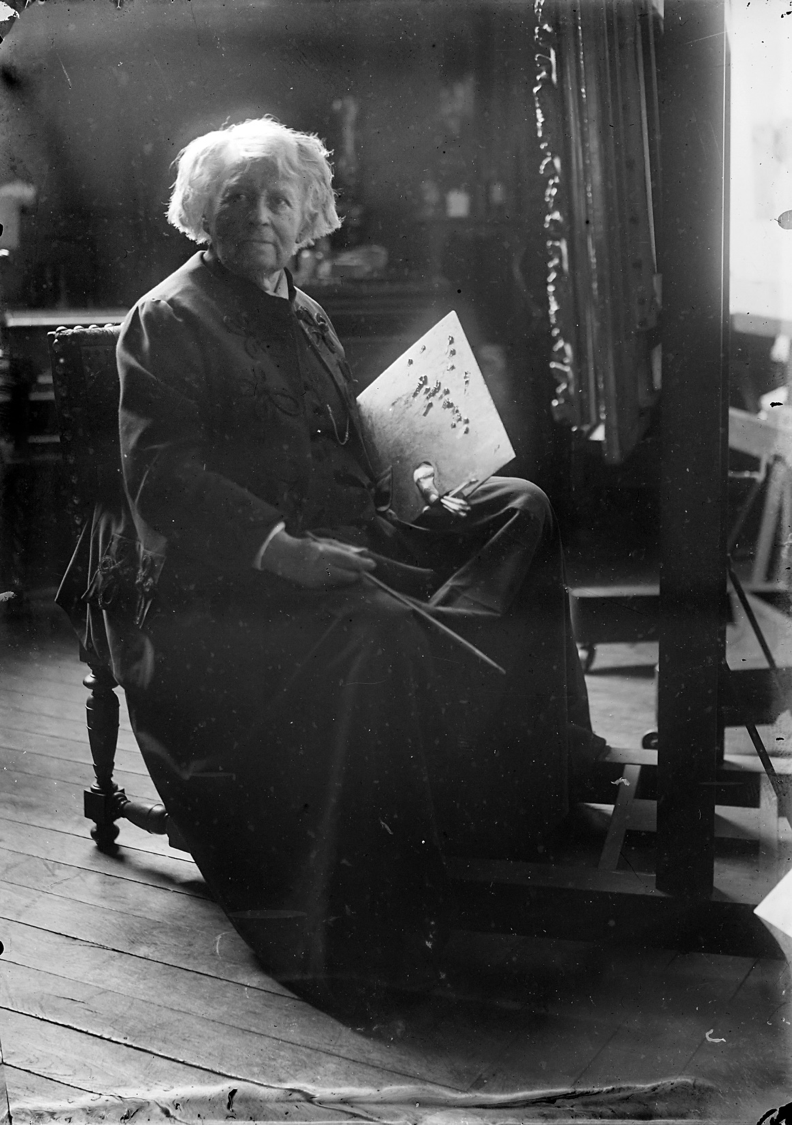

Rosa took full advantage of the permissions granted by creating something of a trouser-based uniform for herself while she worked. According to the archivist at Château de Rosa Bonheur, it was only really when she posed for the occasional portrait that she’d wear a dress.

An essential feature of her “uniform” was the red ribbon adorning almost all of her jackets: a mark of her Légion d’Honneur. Not only was Rosa Bonheur the first woman to receive the distinction, Empress Eugénie, the last French Empress as the wife of Emperor Napoleon III, was the first woman to bestow it.

At the age of 11, when her mother died, Rosa is said to have made a vow to never marry and never have children, to avoid the heartache of love lost. Throughout her life, she remained loyal to this vow. Despite never marrying or having children, the artist is believed to have been in two significant relationships: the first with her childhood friend, Nathalie Micas. The two were inseparable for 40 years, until Nathalie’s death, after which Rosa encountered fellow artist, Anna Klumpke.

Of Anna’s most notable works, several are of Rosa. She went on to become Rosa’s partner, biographer and sole inheritor. Originally from San Francisco, Anna would frequently travel back and forth between continents, until the Second World War broke out and she found herself trapped – for better or for worse – in America. The mid-1930s would be the last time the house was inhabited.

Over the years, ownership fell into the hands of the French government, who would open it sporadically and unceremoniously, but for the most part the house gathered dust. According to Katherine Brault, when news spread that she had bought the property with the intention of opening it as a museum, boxes of Rosa’s affects began to appear anonymously at the front door. Perhaps a sign of approval from the locals, who now see the value of the heritage held within the various objects they’d, let’s say, been keeping safe.

Thanks to Katherine’s meticulous maintenance, it’s not only possible to walk in Rosa’s footsteps through her workspace, but experience life as she might have done by staying the night in one of four guest suites in the artist’s private quarters.

Discover the Chateau de Rosa Bonheur.