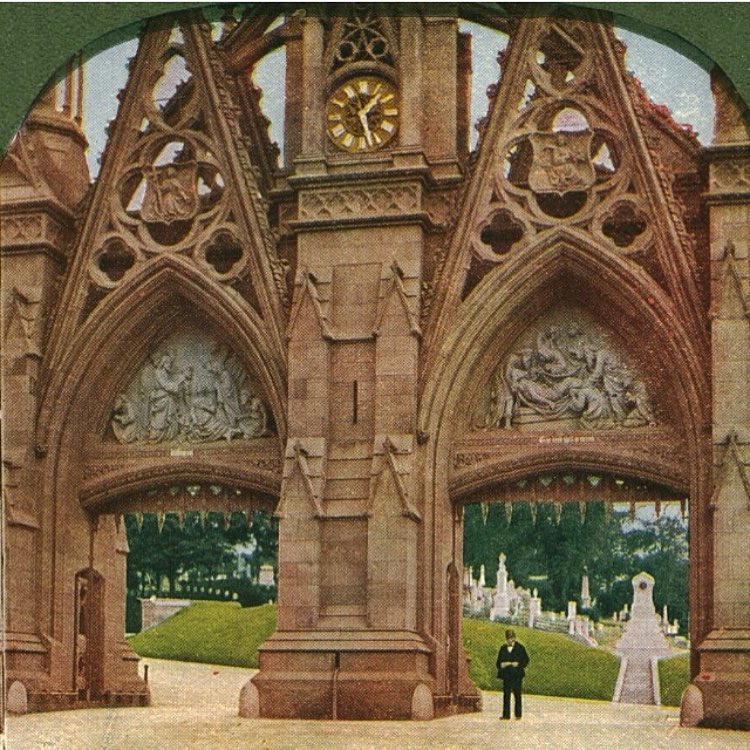

When it comes to green spaces, we’re a bit spoilt in New York City. There are over 1,700 parks (even if it doesn’t always feel that way) for our picnics, parties, and general frolicking to unfold. But 150 years ago, parks were still a privilege for the upper-class in America, if they even existed at all. So folks flocked to the next best thing: the cemetery. There, in the shady knolls of Boston’s Forest Hills Cemetery, or amongst the gothic gates of Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery, 19th century Americans got to engage in their two favourite pastimes: bonding with the dead, and feeling their pastoral oats. Elaborate walkways, gardens, and follies abounded in the cemeteries – one even had a liquor license – in a way that’s made us wonder why cracking open a cold one with the deceased ever went out of style…

Europeans first ran into the issue of overcrowded churchyards, so they invented the sectarian, “rural cemetery”. The very first was Paris’ Père Lachaise in 1804. Back in the day, it was outlandish for Westerners to think they’d be buried anywhere but the churchyard. Then came urbanisation, overpopulated cities, and a rising mortality rate from Yellow Fever, Tuburculpsis, Cholera, etc. – people were dropping like flies, and there was nowhere to bury them with dignity. In the 1880s, one census found that the “urban mortality rate was 50% higher than rural mortality rates” in America. Rural cemeteries were on the outskirts of cities, spread out over massive plots of land, and thus considered less prone to disease.

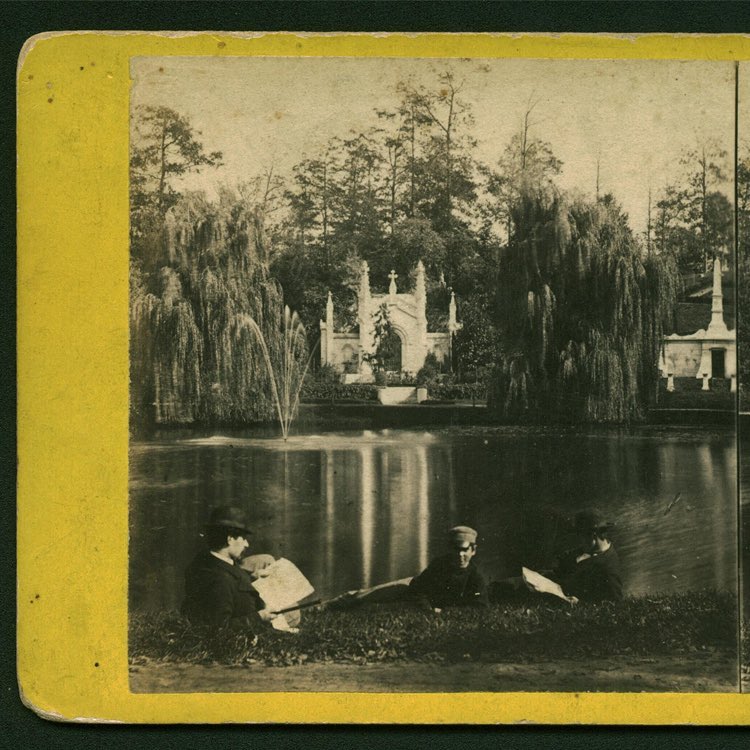

The United States took note, as well as inspiration from the sprawling Victorians gardens of Europe. After all, if they wanted to entice people into rural cemeteries, they had to find a way to make them appealing. In Massachusetts, there was Forest Hills Cemetery with its arboretum and sculpture garden, as well as the massive Mount Auburn Cemetery, whose 175-acres touted meadows, forests, follies, ponds, fountains and more. Often, they were called “grave gardens.”

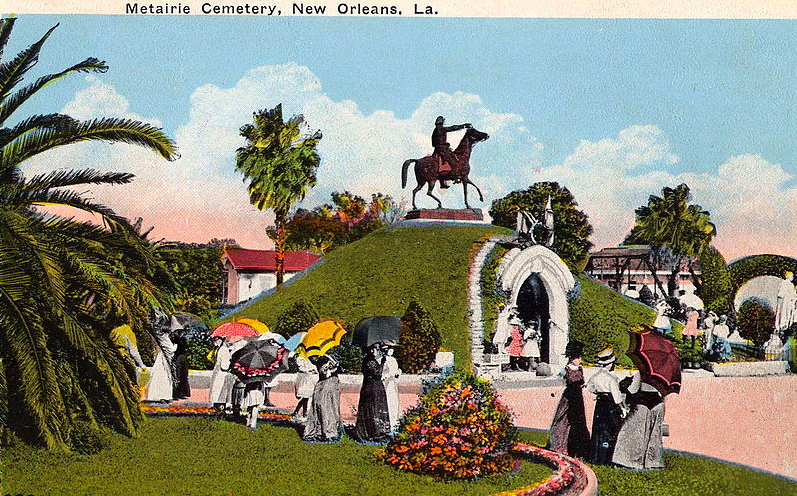

Even if you didn’t have an ancestor to picnic with, rural cemeteries became a place for city goers to retreat for a day. Nannies could take the baby for a stroll in the pram, while women paraded the avenues with parasols in one arm, and a man on the other.

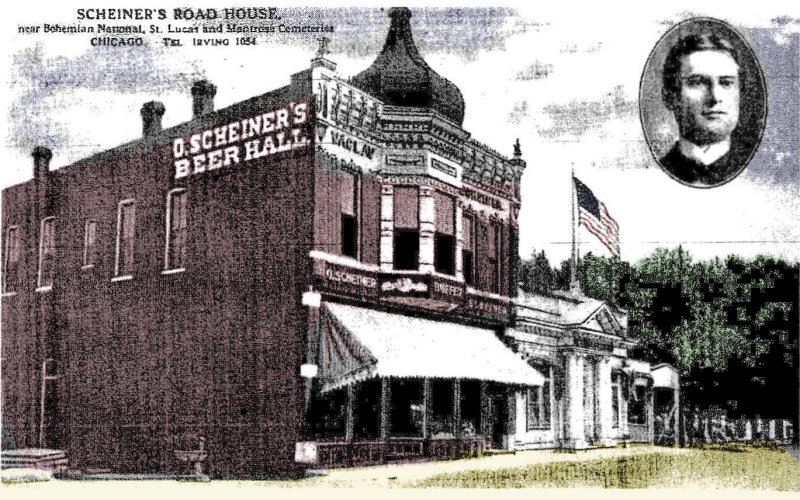

In Chicago, the Bohemian Cemetery even had its own liquor license, what with Scheiner’s Beer Hall and Road House being adjacent to their greenhouses. It also boasted three different picnic groves for people to reconvene after a ceremony, Scheiners, Atlas, and Nagl’s Grove.

Meanwhile, the great American parks were underway. Sure, the 50 acre Boston Commons, est. 1634, was the first official park is the United States – but it would be nowhere near as large as Central Park (778 acres), est. 1853, or Golden Gate Park in San Francisco which was built, in part, to deliberately one-up its East Coast rival at 1,013 acres filled with even more attractions (there’s still a paddock of bison in the park. Bison). Cemeteries, as the misfit parks they were, followed suit.

Unfortunately, the post-war years left Americans more shell-shocked than ever. Something shifted (or perhaps peaked) in the American attitude towards death as a taboo and tragic subject in the 1950s. It became so much more of an out-of-sight-out-of-mind matter – partially because people were living longer, and making more money (hello, Baby Boomers).

As a result, the atmosphere of cemeteries grew decidedly more sterile, and the desire to hang in cemeteries dissipated – which isn’t to say Americans had been literally dancing over their loved ones’ graves all this time (leave that to the Romans). But it had an actively engaged role in the community. A cemetery was a place of quiet, nature and contemplation. It made room – mentally, and physically – for folks to digest all the nuances of their grief while the world didn’t just pass them by, but meet them at the cemetery gates.

We’re happy to say that the pendulum is starting to swing back to hanging in cemeteries. More and more historic cemeteries are finding ways to reignite the century-old flame they had with the public, and not always in a macabre, spooky way. The Hollywood Forever Cemetery has movie nights. Mount Auburn Cemetery has begun hosting a book club, twilight walking tours, and ‘treasure hunts’ for fourth graders. There’s even a Cemetery Picnic Club floating around the Twitterverse.

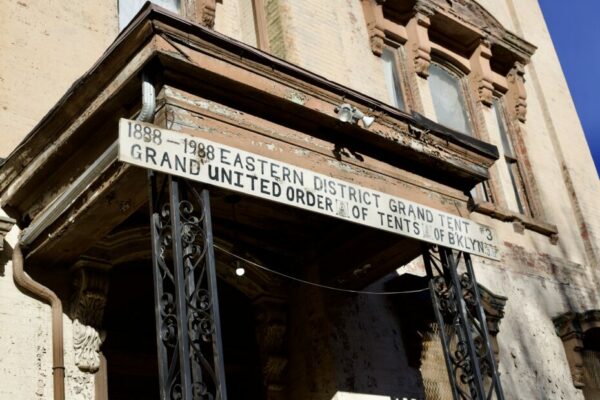

“We all experience and process death in different ways,” explains Brooklyn’s beloved Green-Wood Cemetery, one of the country’s first rural cemeteries, on its eagerness to engage with the community. A visit there today is nothing short of charming, complete with a little green trolley that will shuffle you around from its notable sites, like the historic hilltop of the “Battle of Brooklyn” that took place in 1776. As the highest point in Brooklyn, it’s got sweeping views of the city, complete peace and quiet, and four lakes for enchanting summertime evenings…

“Those interested in the various human perspectives on death, dying, and memorialization will want to reserve a space for ‘Cemetery Shorts’ [this summer]” says the Green-Wood staff on their movie nights. The grounds also host art exhibits, and teach beginner’s bee keeping (did we mention there’s a whole, secret world of Bee Villages in NYC?).

Green-Wood (not Greenwood, mind you. Locals are touchy on that) was itself founded on a curious bedrock back in 1838. It’s got lush, undulating grounds that you won’t see elsewhere in NYC, because it’s actually on the site of an ancient glacier called “the Laurentide ice sheet”. Notable graves include the author of The Wizard of Oz, Basquiat, and Leonard Bernstein. Local lore also says the vibrant monk parakeets nesting on its grounds came all from Argentina by way of a shattered crate at JFK in the 1960s. As a cemetery, it’s astounding. As a park, it’s one of the city’s best kept secrets.

One last tip for the wise? Don’t miss the October nighttime tour…