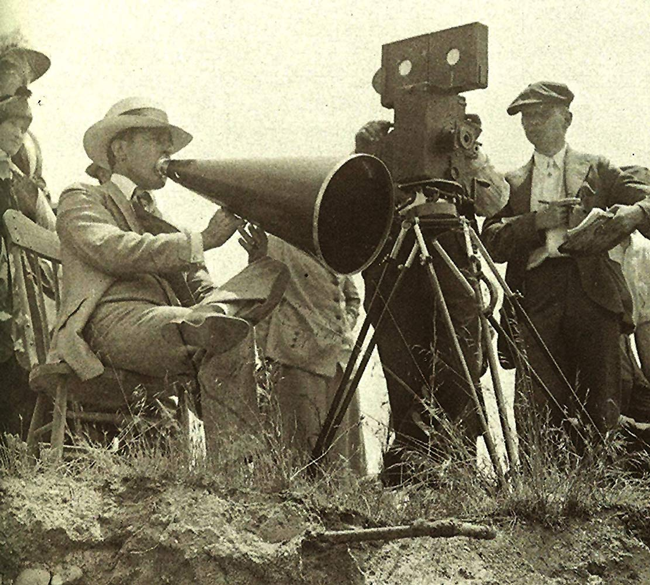

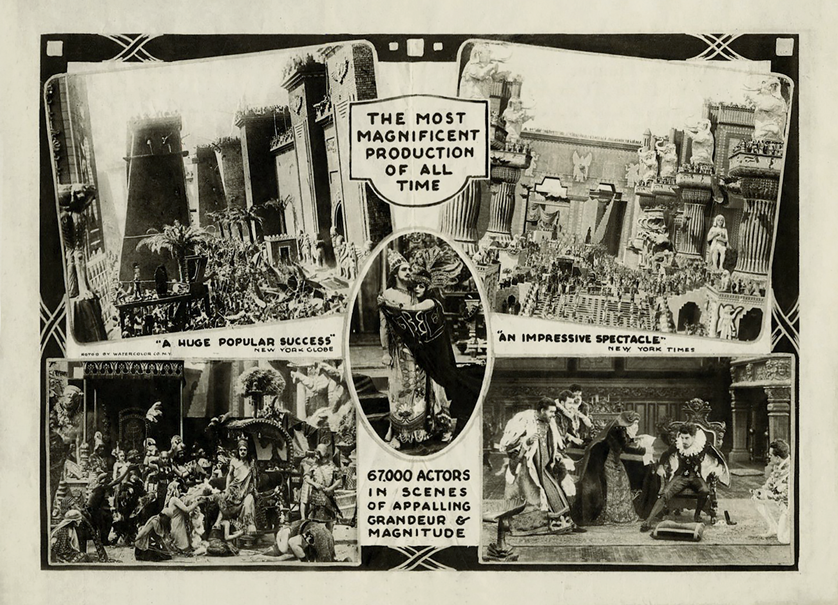

If you build it, they will come. And if they don’t, you’re screwed. Such was the case for Mr. D.W. Griffith, the infamous movie mogul behind the best worst movie ever made: the silent epic Intolerance (1916). Griffith became the emperor Los Angeles for the picture, creating a veritable city of 300-ft-tall Judean walls and elephant idols, hiring over 3,000 painstakingly outfitted biblical extras to populate his pop-up paradise on an otherwise sleepy Sunset Boulevard. Why? Because at his core, Griffith was a seedy character. In many ways, Intolerance was his manic, ego-fuelled quest for public forgiveness and greatness. This was the sizzling beginning of big budget pictures, and it was built on a foundation of scandal, glamour, and disaster. It wasn’t just a movie. It was an awakening.

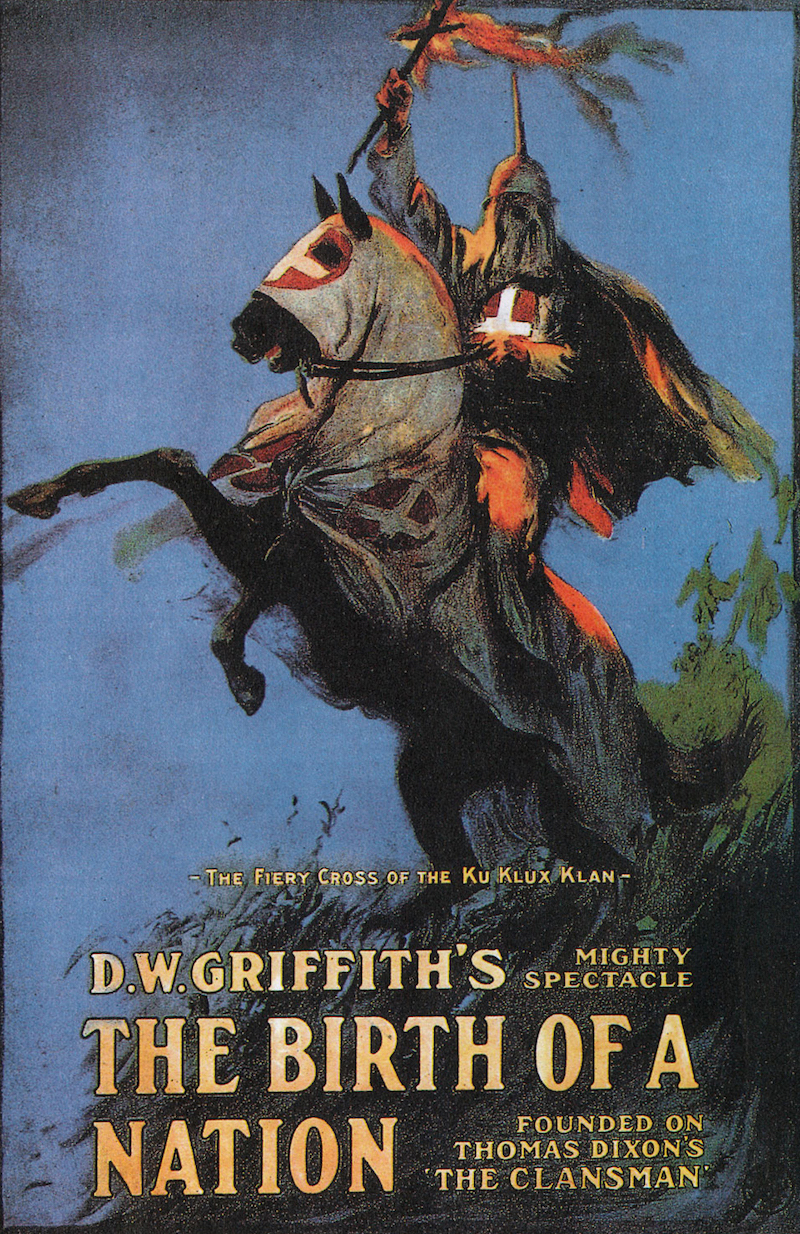

First, we have to roll up our sleeves and dig into Griffith’s precedent film, The Birth of a Nation (1915). Easily the most-hated movie in America today, it was a Civil War epic that painted the Klu Klux Klan as a heroic force and President Lincoln as an aimless leader. “It was originally known as The Clansman,” writes historian Melvyn Stokes, and was actually “the first ‘blockbuster’ in US history.” Prior, the US had mainly 15 minute-long, one-reel gag flicks. Birth of a Nation was 12 reels, and synthesised acting, music, and marketing on an unprecedented scale. Whether they loved it or hated it, “no one who saw it,” wrote critic Marjorie Rosen in 1973, “could deny its potency.”

To date, few other films have demonstrated the powder keg bond between media and politics; The Birth of a Nation was the first film to be screened for the White House and the Supreme Court (to a standing ovation), and became a driving force behind the resurgence of the KKK. To date, the film has only been surpassed by Titanic (1997) and Avatar (2009) in nominal earnings.

Intellectuals fawned over its implications at cocktail parties. It sparked public praise and protest, which meant that Griffith – as a director, and a moral American – put his career in a somewhat precarious position.

Despite (or perhaps thanks to) the controversy, the movie was a hit and made him feel like the sky was the limit for the next picture. It had to be even bigger – but it also had to be sweepingly ‘moral’ to silence any critics suspect of his racism. Thus, Intolerance (oh, the irony) was born…

Griffith decided to try rolling four movies into one by tracing 1. the fall of Babylon 2. a Judean story leading up to the crucifixion of Jesus 3. a French Renaissance tale about Protestant Huguenots and 4. a (then) modern tale of the conflicts between capitalists and blue collar workers. So yeah, not light viewing.

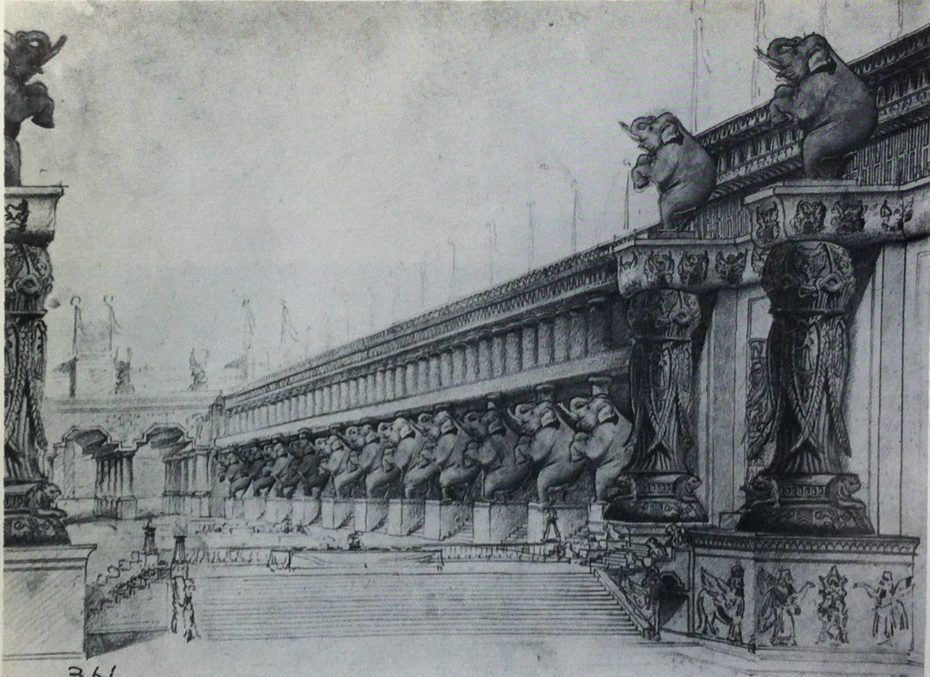

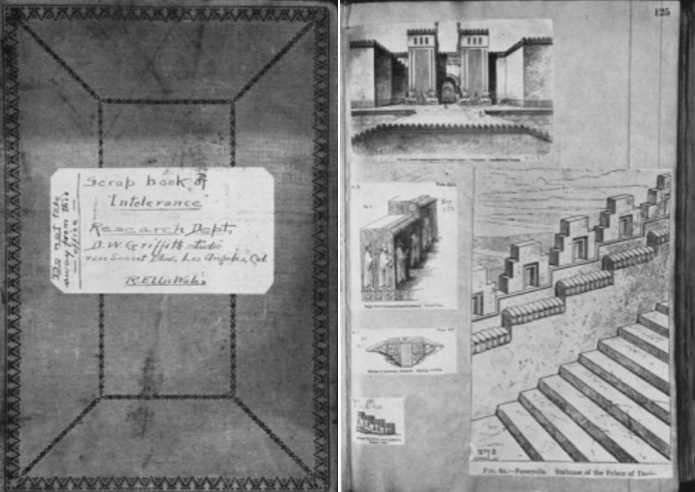

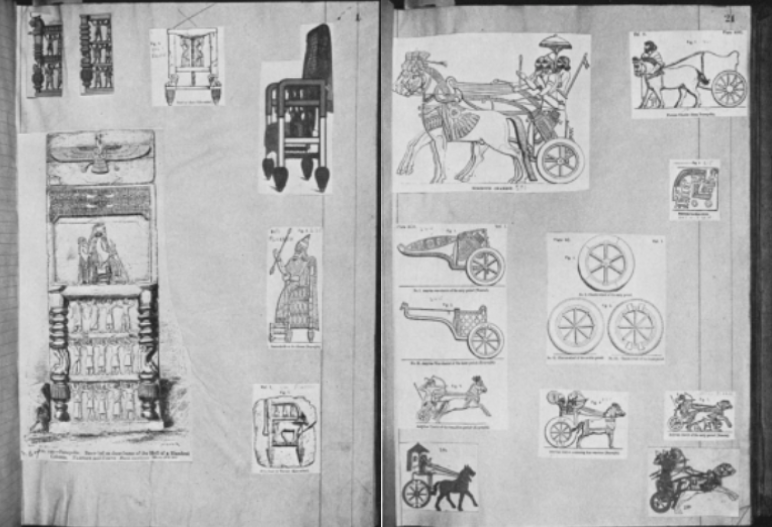

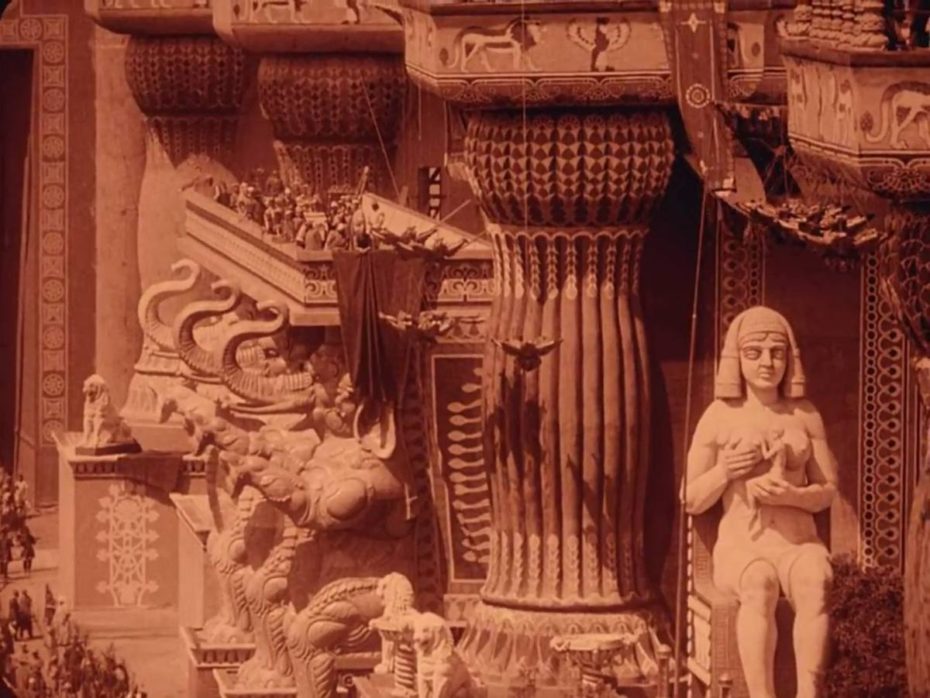

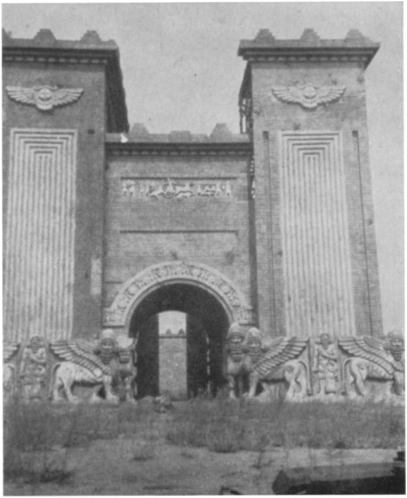

The bulk of Griffith’s energy went to outfitting the Babylonian chapter, which he considered to be the film’s heart. The best of the best in the business got to designing it.

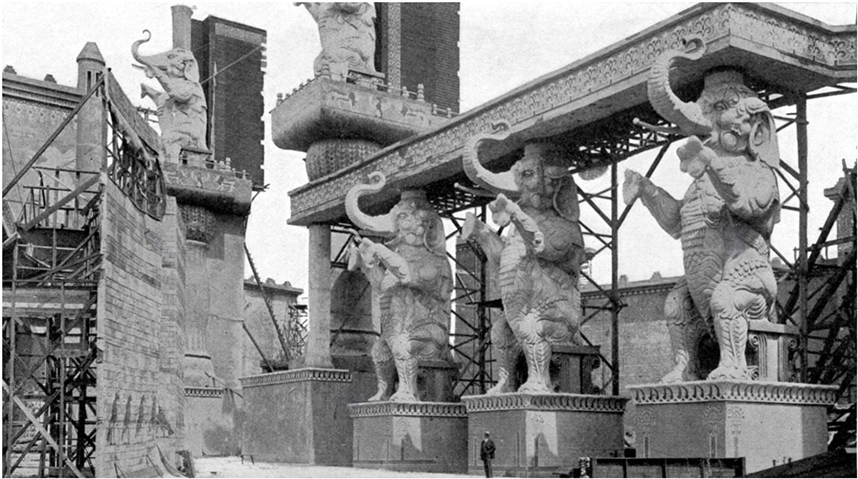

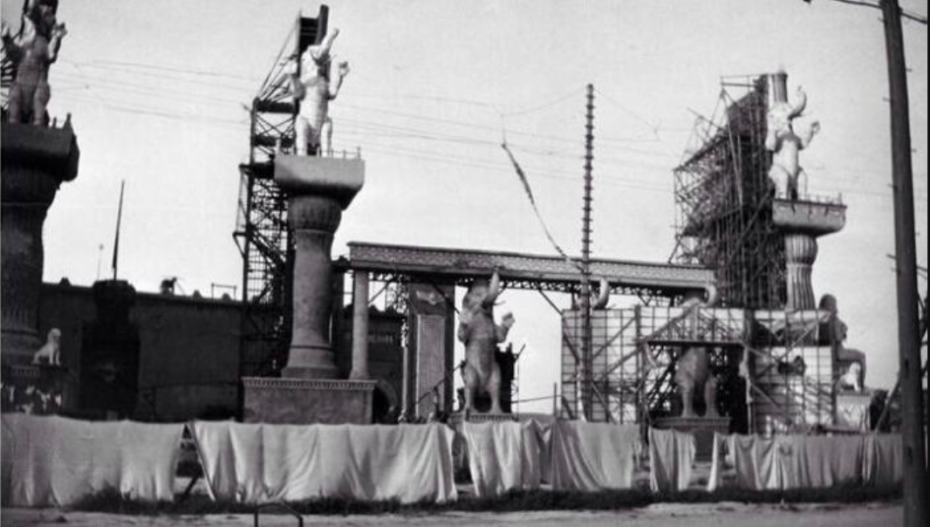

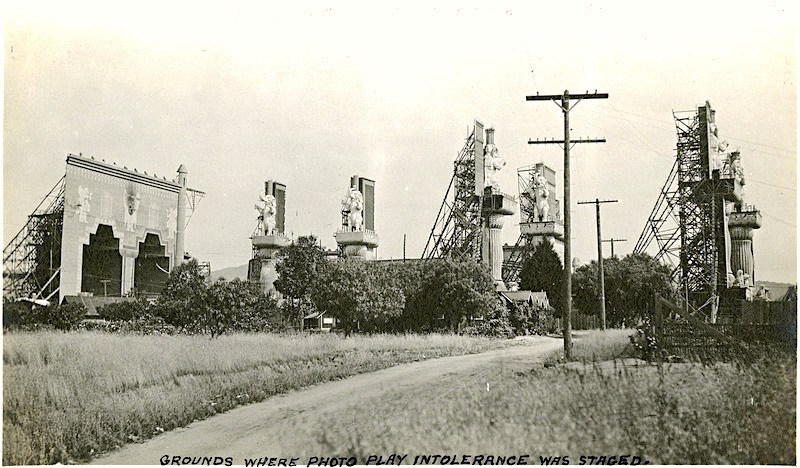

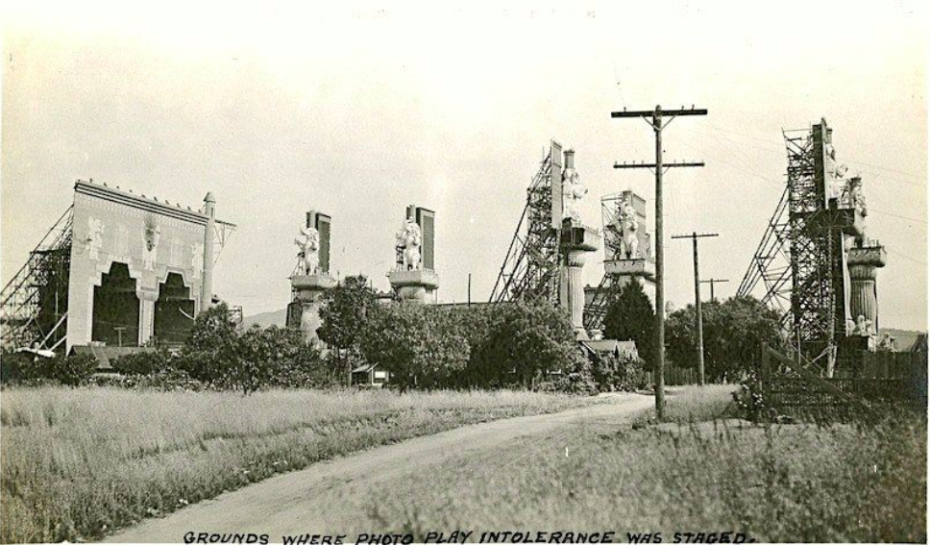

At the crossroads of Sunset and Hollywood Blvd, they mounted “plaster mammoths perched on mega-mushroom pedestals,” as Kenneth Anger famously wrote in his eponymously named Hollywood Babylon, a smutty industry tell-all that was banned in the US for some time.

“Belshazzar’s Feast beneath Egyptian blue skies,” Anger continues, “spread out under the blazing California sun: more than four thousand extras recruited from LA paid an unheard-of two dollars a day plus box lunch, plus carfare.”

Anger had a talent for embellishment, but he was pretty on-the-nose with Intolerance; the great feast scene alone cost $250,000. In 1915. According to the Census, a decent annual salary after income tax that year was $687. Griffith’s extras alone cost him $12,000.

This is the part where we blast you with movie stills:

There would be chariot racing, massive thrones and altars. There would be hanging gardens, whose lushness was upstaged only by the lavish parade of extras whose costumes dripped in gemstones. The hullabaloo around the picture was thrilling. Neighbours in low slung bungalows watched as the monolith of a set grew, and grew…

One day, it stopped. The filming was done. The people of Babylon went back to their day jobs, leaving a massive, silent void in their wake – and when the movie premiered, no one really knew what to do with it. At three-and-a-half-hours long, and not exactly of the cheeriest of content, it wasn’t watchable in one sitting. Griffith was left with no money, and a lot of egg on his face. But his Babylon lived on, taunting him and the rest of LA on the horizon line.

In hindsight, the film had tread exciting new technical and stylistic territory. The camera favoured shots and angels that didn’t necessarily forward the plot, but rather savoured its detail and ambiance. Visually, it was a treat. Plot wise, it was meandering at best. Critics said it was style over substance, and they weren’t wrong. But what’s so bad about a film whose style is its substance? These days, it’s considered a nutty, art house masterpiece.

It had also become the ultimate cautionary tale: in one year, Griffith went from being the most impressive director in Hollywood to a man with barely a penny to his name. Henceforth, he’d have to rely on outside backers. Intolerance was the peak of his ambitions, the ghost of a dreams that still rotted on the boulevard, sprouting weeds that prophesied the fickleness of the industry and was parodied by Buster Keaton in 1923’s Three Ages:

But the thing about Hollywood, is that it loves a good comeback. The original Intolerance set was totally razed by 1922, but it found life in the new millennia when, in 2001, an LA shopping centre recreated portions of the set for its design – the result is a tacky, undeniably impressive commercial centre called The Hollywood and Highland shopping mall.

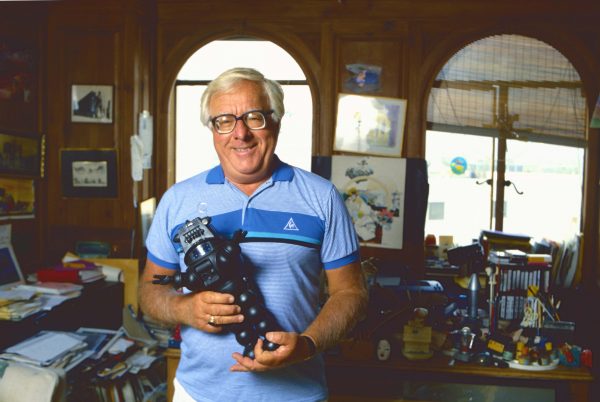

As if the story couldn’t get any stranger, the concept appears to have been the idea of the late Ray Bradbury, author of the dystopian classic, Fahrenheit 451 (1953). Bradbury called himself “the accidental architect” and happily shared his ideas for revitalising LA’s sense of community in ways that payed homage to its cinematic history. “Gathering and staring is one of the great pastimes in the countries of the world,” he wrote, “But not in Los Angeles. We have forgotten how to gather. So we have forgotten how to stare.” The architect of the local Glendale Galleria, which opened in the 1970s, said his team actually took notes on Bradbury’s suggestions for “reviving retail districts” with central, circular spaces in mind. Bradbury was also a big champion for installing monorails throughout the city – who knows, in another life, the Midwestern icon could’ve radically transformed LA.

In that vein, Bradbury (who died in 2012) said the city should absolutely bring back Intolerance‘s set – and this time, take care of it. “I told them that somewhere in the city, they had to build the set,” he wrote in an essay published posthumously in The Paris Review, “The set, with its massive, wonderful pillars and beautiful white elephants on top, now stands at the corner of Hollywood and Highland avenues. People from all over the world come to visit, all because I told them to build it. I hope at some time in the future, they will call it the Bradbury Pavilion.”

There you have it. The nitty gritty rise of the modern movie business, from an All-American KKK blockbuster, to the rebirth of its gardens of Babylon in a strip mall. A strange way to bookend one man’s career, no doubt – but that’s Hollywood. If anything, let us celebrate Intolerance not in fond memory of Griffith, but in homage of the industry artisans whose stories often go unsung.

PS. You can watch Intolerance online below