Writer. Dandy. Philosopher. Creature of the night. Quentin Crisp was so many things, but above all he was steadfastly himself. Sting dedicated his song, “Englishman in New York” to Crisp. The New York Times memorialised him as a revolutionary “Writer and Actor on Gay Themes” in light of his 1968 book, The Naked Civil Servant, a pain-riddled but quippy coming-of-age memoir on his pursuit of acceptance as a genderqueer man – a steep challenge before the gay rights movement. Unearthing forgotten interviews on Youtube with the one and only Quentin Crisp is a sure way to fall down the rabbit hole. But here we go again …

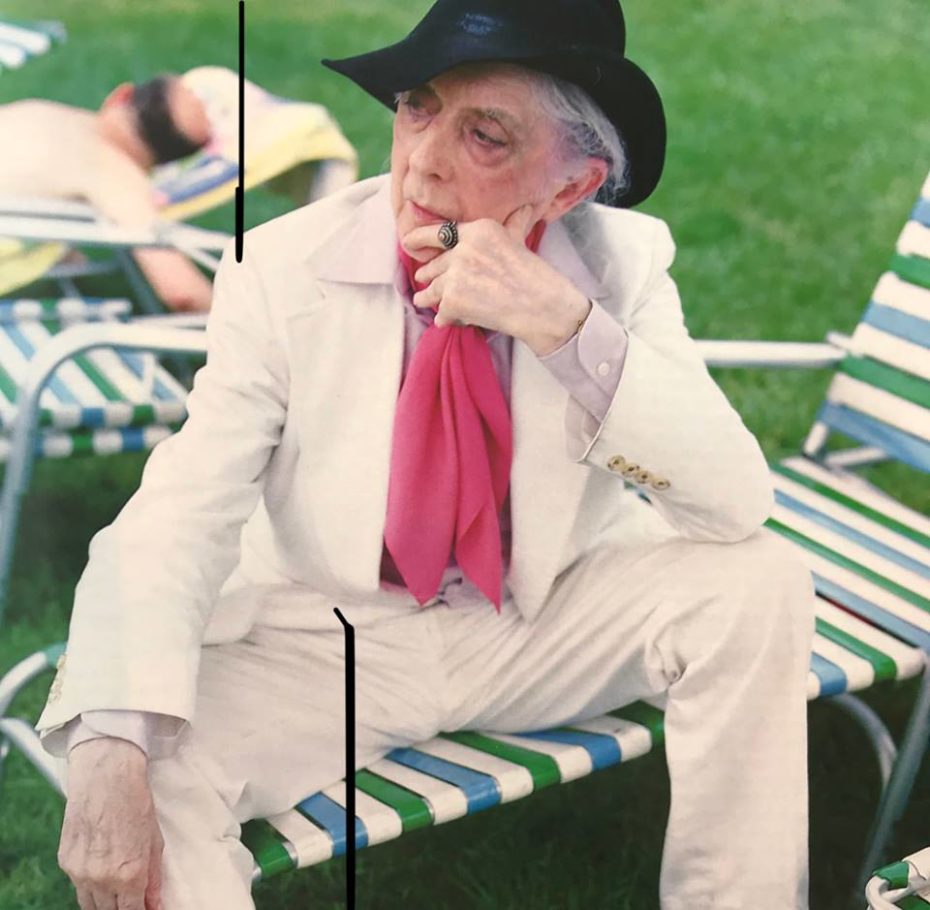

Having recently celebrated 50 years since Stonewall, as a whole, we seem to be doing a better job of understanding LGBT history surrounding the gay rights liberation of the 1960s, 70s & 80s – but what about the heroes that were born too early? As a British eccentric in the 1920s and 30s, Quentin Crisp was a veritable Oscar Wilde reincarnate. At the onset of WWII, Crisp was declared as “suffering from sexual perversion” and turned away from service. During the London’s 1941 Blitz, whilst everyone else was hiding in bomb shelters in the dark, Crisp, who’d stocked up on makeup and five pounds of henna to die his hair, pranced through the city streets picking up American soldiers. As a man about town in Manhattan’s Meat Packing district in the ’80s, he was a legend: an LGBTQ icon who faced bigotry armed with a head of lavender hair, golden eyeshadow, and a jaunty fedora. It is difficult, perhaps even laughable, to try and sell Quentin Crisp better than he sells himself. Plus, nothing beats his Alice-in-Wonderland-Caterpillar pitch. So we’ll let him do the talking first:

The interview was filmed in 1970, at his single-room apartment at 129 Beaufort Street, Chelsea, which he openly admits to the film crew, hadn’t been cleaned since the day he’d moved in 30 years ago. Quentin famously wrote in his memoir The Naked Civil Servant as a piece of advice to housewives: “After the first four years the dirt doesn’t get any worse.”

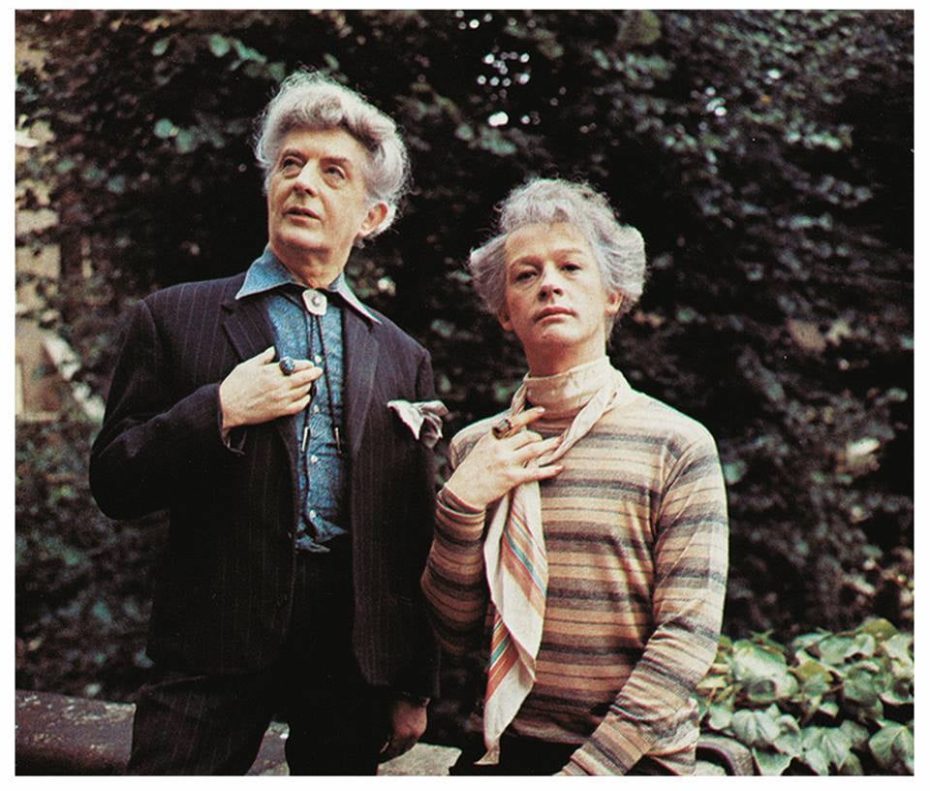

Looking every bit the genderless dandy, decades before Bowie was on the scene, Quentin was one of London’s most colourful residents. He used effeminate fashion as means for exploring his gender identity, but also to cause a stir in a society and time in history where it was dangerous to be an openly gay person.

“The great barrier between me and the outer world is my appearance… my hair was henna’d, my eyelids were gold, my fingernails and my toenails were gold, and I was blind with mascara and dumb with lipstick. sometimes it led to my being beaten up… but this of course I had to expect… it is people’s way of saying they don’t accept the way I am.”

So why not go to Paris, where he wouldn’t have caused so much of a stir?

“I wanted to survive the stir. the idea was to outlive it… to show that people like me had to go on living. That they had to take their laundry to the laundry, eat their meals in restaurants, they had to go to work and come back. This is what people had to learn …”

Public acceptance only came for him in his twilight years, through adaptations of his writings for TV and theatre. Actor John Hurt got his big break playing Quentin in a 1975 the television version of The Naked Civil Servant, making both of them stars. But for much of his life, Quentin suffered greatly for his fearlessness.

“He had people beating up on him on a daily basis, largely with the consent of the public,” said Sting after the pair became friends over dinner in 1968. “Quentin is a hero of mine, someone I know very well”.

“It takes a man to suffer ignorance and smile, Be yourself no matter what they say.”

(An Englishman in New York – Sting)

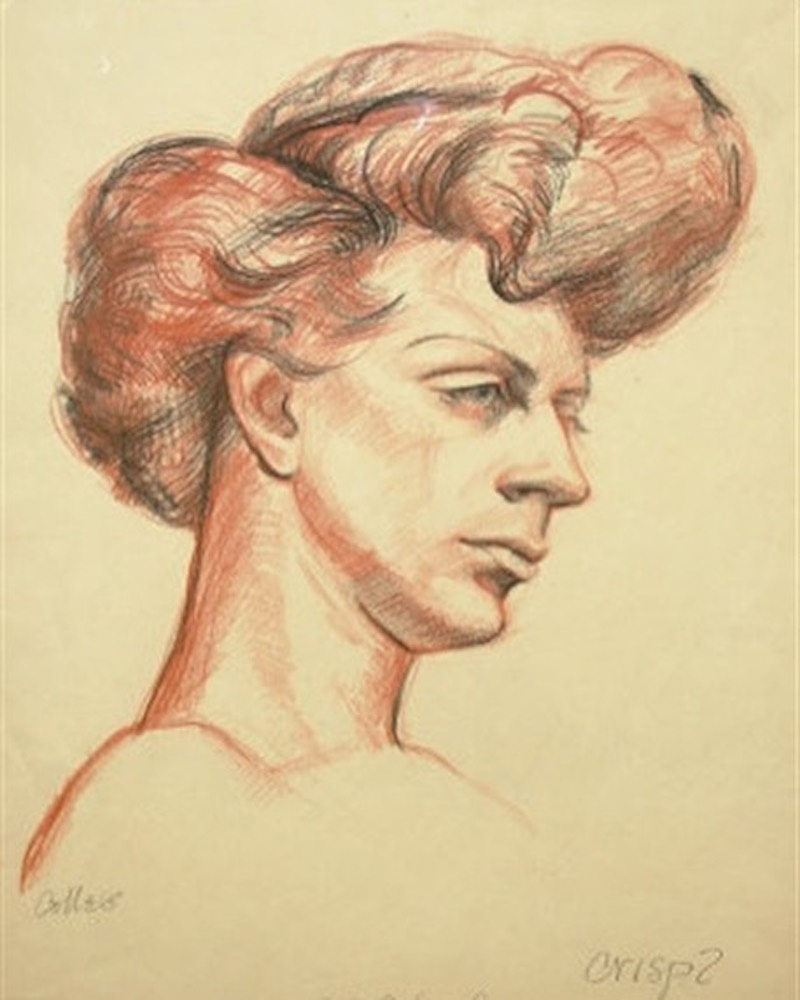

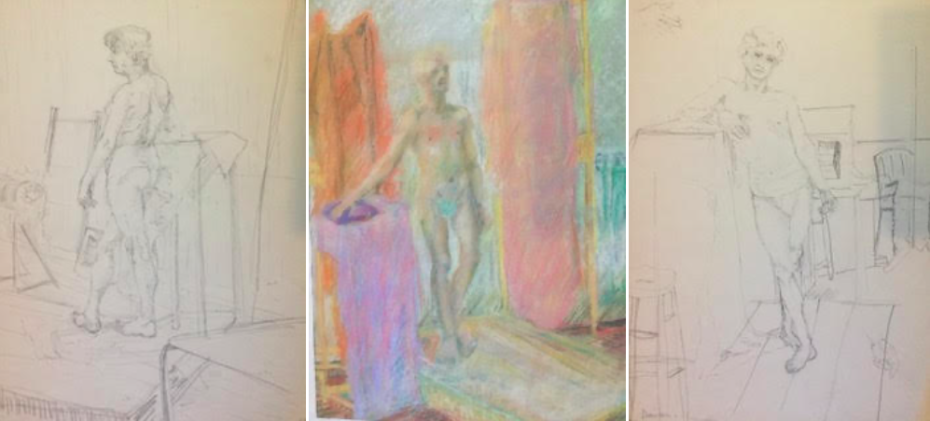

Ostracised in his youth for his effeminate manner and dress, Crisp turned to prostitution for six months to make a living before finding work as a book illustrator, an engineer’s tracer, and a nude model for drawing classes. He had formally studied art, but never became a painter. One of Messy Nessy’s readers, Dimity Dawson, actually wrote in with some personal sketches of Crisp. “[They’re from] life drawing classes held in the evenings, in the ’60s at Beckenham Art School, which no longer exists!” wrote Dimity, “Crisp […] had died, purple hair, nail varnish, and make up. He wore a floral pouch. As a naive 16-year-old, I was somewhat bemused. He struck very camp poses, and was a fabulous model!”

On sex work, his logic was deceptively simple. “I’ve been a male prostitute,” he said in the above video interview, “and this worries people. Prostitution in general worries people, and I can’t understand this because to me the only excuse that you can find for the disgrace of sex is that there might be money in it. Otherwise it’s a wanton form of self enjoyment – and you know what [God] thinks about happiness. You’ve got to be able to explain it in some way. For whatever is done for money, is sacred.”

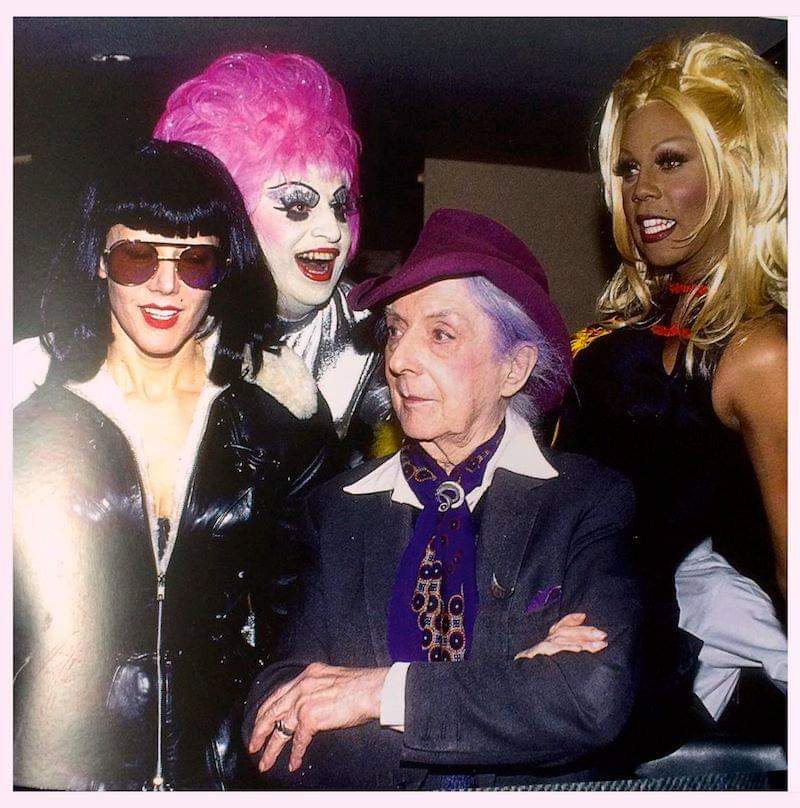

Nights in 1980s Manhattan were spent dancing with RuPaul, and Divine. But the mutual vulnerability that builds human bonds – the one thing Crisp didn’t wear on his sleeve – never fed into his friendships. In a 1998 piece for Independent, his pal Andrew Barrow confided, “On stage and in private, he rarely says the word ‘love’ without giving it a mocking twang.”

Crisp was 59 years old when The Naked Civil Servant was published. Success came in tandem, and context with, the sweeping sexual and cultural revolution of the ’60s and ’70s.

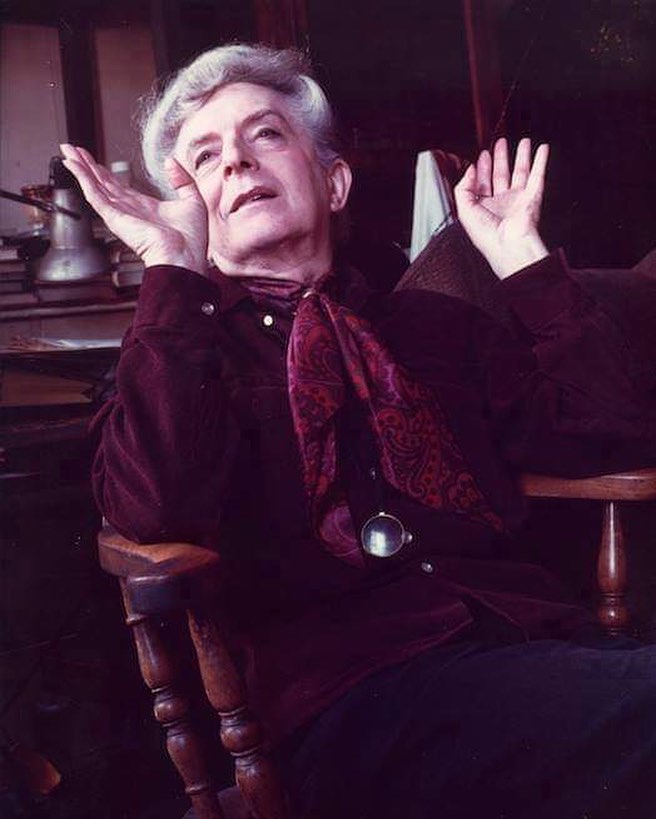

He became in demand on the talk show circuit for his spicy opinions and often performed a one man show (part monologue, part Q&A). Many of his proclamations were outright scandalous. The world swooned for Lady Diana; but before her tragic death, Crisp had less favourable opinions on her choices. “She was Lady Diana before she was Princess Diana, so she knew the racket,” he said, “She knew that royal marriages have nothing to do with love. You marry a man and you stand beside him on public occasions, and you wave, and for that you never have a financial worry until the day you die.”

His relationship with the LGBTQ community was often tense. “I’m a minority within a minority”. He often gave conflicting statements about gay liberation, dismissing of the struggle for lesbian and gay equal rights, and seemingly contradicting himself from one interview to the next.

In later interviews, Crisp said he wished he’d been born a woman. “[It’s] the only thing in my life I have wanted and didn’t get,” he said, “I feel that then everything would have fallen into place … the thoughts in my head would not any longer have been remarkable. They would have been acceptable… If the operation had been available and cheap … I would have jumped at the chance. My life would have been much simpler as a result”.

Some LGBT campaigners suggest he became bitter with age; resentful that he was no longer the “only queer in the village”. Still, he attended numerous Pride events over the years in NYC and beyond to become a cult queer figure. Quentin told a journalist, “once the public gets bored with homosexuality, then freedom with be here.”

For every step Crisp took forward, there were ten hurdles to set him back. Yet, still had the wit to say things like, “If at first you don’t succeed, failure may be your style.” Of course, they were just the witticisms that made him famous. Quentin Crisp was a magnetic raconteur; an unpredictable storyteller – and once you’ve found him, an English eccentric far too fabulous to forget.

Neither look forward where there is doubt nor backward where there is regret. Look inward and ask not if there is anything outside you want, but whether there is anything inside that you have not yet unpacked.

Quentin Crisp

Keep up with the latest on Quentin Crisp, and order his memoir, The Naked Civil Servant, here. Photos via The Last Word with Quentin Crisp FB page. “The Last Word” was written by Crisp with the help of his best friend, Phillip Ward, who tape-recorded and later transcribed Quentin’s words between 1997-1999, and is co-edited with Laurence Watts.