A guide to wedding dress inspiration isn’t exactly the kind of thing you’re likely to find on Messy Nessy Chic. Then again, it’s not everyday that the founders of the MessyNessy team get hitched! As Nessy and Alex tie the knot this weekend, we’re holding down the fort at the MNC HQ and thought we’d go around the world in a few wedding dresses…

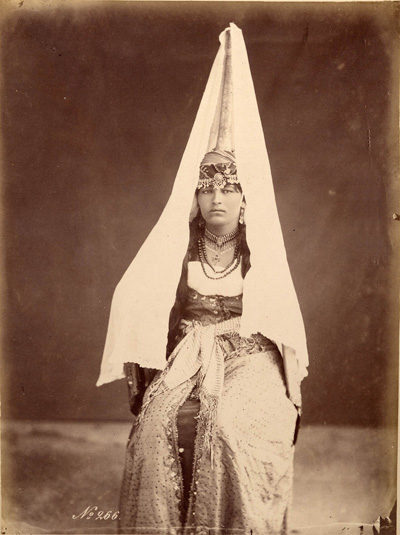

Kazakhstan

Truly princess-worthy. Kazakhstan’s traditional bridal garb often hinged on blinged out, conical headgear that most Westerners will compare to a “hinna” (the word for the medieval “princess hats” we’re so familiar with). In Kazakhstan it’s called a saukele, and it’s hands down the priciest part of a bride or groom’s wedding outfit.

The headdresses were made with precious stones and metals, and often topped with an owl feather pom pom. The height of the saukele evoked the tree of life, and the woman’s role as the heart of her growing family. What we love most about the saukele, however, is that this wasn’t a one-run accessory; women brought it out to wear during funeral ceremonies as well. A pretty cool way to bring things full circle, and destigmatise death if you ask us!

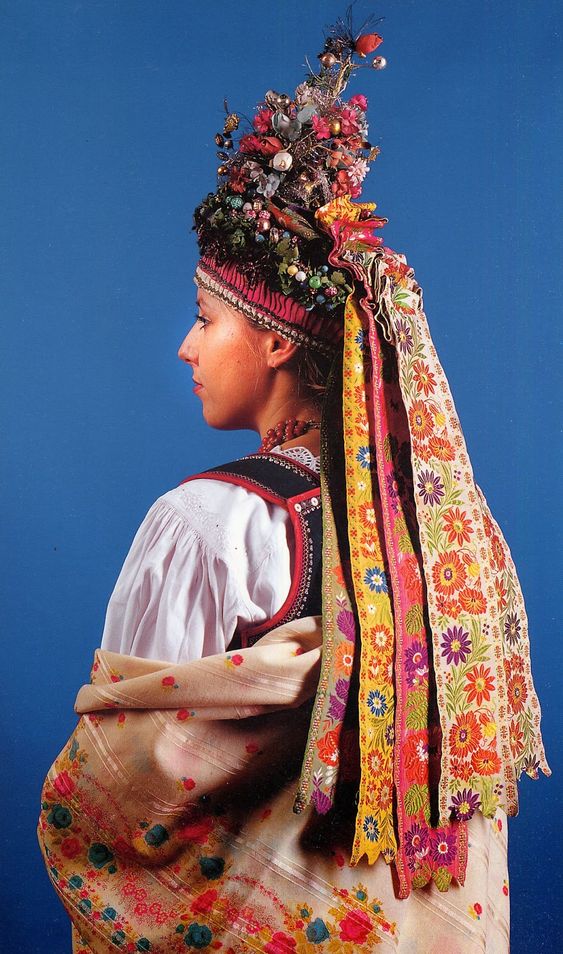

Polish Brides

How does your garden grow? Straight out of your head if you’re from the Lowicz area of Poland, where traditional brides wear vibrant bouquets of faux flowers and baubles. It started in the 1860s, when the pańszczyzna (peasant) population was finally free of Russia’s grip and decided it was high time to start celebrating their newfound freedom in style, which is why we’re such a fan of the floral headdresses: they’re a symbol of marital union, as well as cultural liberation.

Polish author Ladislas Reymont described a bride’s style of dress in The Peasants: “Her striped skirt of rainbow tints; her black highlows, laced up to the dainty white stockings; her corset of velvet, and strings of amber round her throat…”

It took a village of women to create the headpiece, which pulled from pre-Christian, Slavic traditions (#PaganLife forever) by incorporating floral and natural elements into its form. The bride’s closest female kin would work tirelessly the night before to build it, and the crown wouldn’t leave the bride’s head for the duration of the wedding day. When the time finally came for its removal, the closest women in her life once again sat her down, and watched ceremoniously whilst the eldest woman plucked out the flowers one by one, combing her hair out of the bridal look and into a wife ready ‘do with a little cap. And as for the groom? By the looks of the photo below, he also had his male peacocking moment:

Spanish & Andalusian Brides

In modern Spain, brides usually wear white dresses, but in earlier times a black lace or silk dress was popular, accompanied by a beautiful lace mantilla – a towering veil, secured with Spanish combs, to complete the look. The tradition actually made its way over from Mexico and Latin America, was popularised across European partially through the paintings of Diego Velázquez and Goya (kind of like the fashion photogs of their day, in a way) and peaked in popularity in the 19th century through Queen Isabella II, who was a big fan. There were few situations in which one could wear the mantilla, which of course included a wedding, other religious occasions, and – most fascinatingly – a bull fight. These days, even Lady Gaga has worn one (see her music video for “Alejandro”).

Bulgaria and the Gora Region

There’s makeup, and then there’s gelena. For centuries, the thick, white paint has been applied to Muslim brides’ faces in the Bulgarian village of Ribnovo for “Pomak” weddings. Elsewhere in Bulgaria, traditional weddings are just as eager to adorn a bride’s face – albeit, with a lavish floral face bouquet (three words we never thought we’d type) in lieu of gelena and sequins:

In Ribnovo, however, the female in-laws are tasked with laying the bride down for the face painting sesh as she closes her eyes, and top off her look with a veil of tinsel, a necklace of money (which the groom will also often wear) and other trinkets. Perhaps most impressively, it’s only when the priest blesses the couple that the bride can open her eyes. It’s a two-day ceremony, but one that relishes in the gradual reveal of the bride, and her transition from single to married life.

In the Gora Region tucked between between Kosovo and Macedonia, you’ll find another population of bridal painting Slavs. Brides whose face paint reads “same, but different” next to their Bulgarian neighbours. The symbolism and style varies a bit, incorporating instead a blue line for fertility on the bride’s brows and three distinct circles (to symbolise the life cycle) on her cheeks and chin.

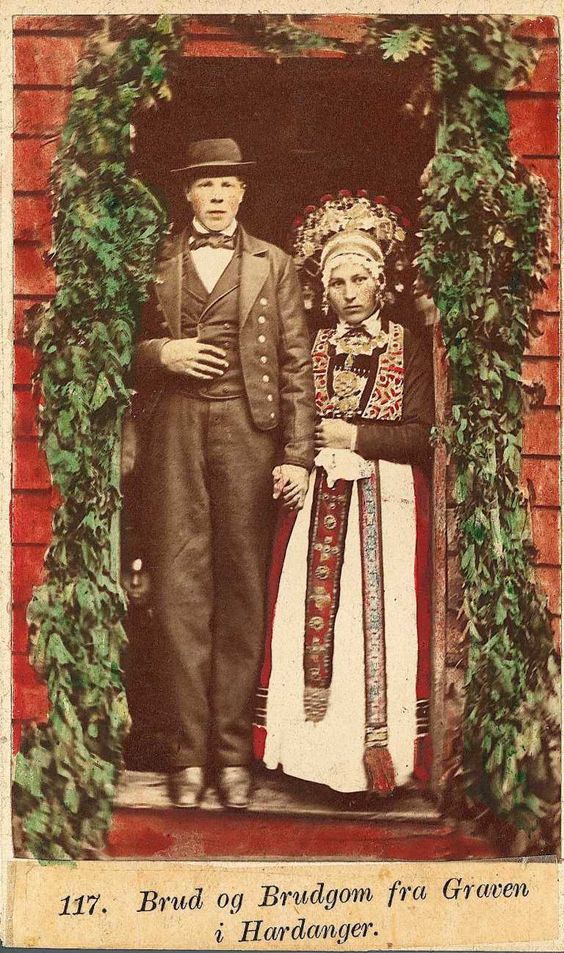

Norwegian Brides

As with Poland, the embellishments on Norwegian wedding garb make for a postcard-perfect, folky scene. But, dare we say it, the Norwegians liked a little more bling in their brudekrone (crown)…

The traditional folk garments are called bunad, and were brought back into fashion in the late 1800s by the great writer and folk dancer, Hulda Garborg, who wasn’t about to see her country’s talent for glam fall to the wayside. As for the crowns? They’re a little extra, but still making a comeback in brides who want to go all-out. By the mid-21st century, it wasn’t uncommon to see micro-crowns on brides:

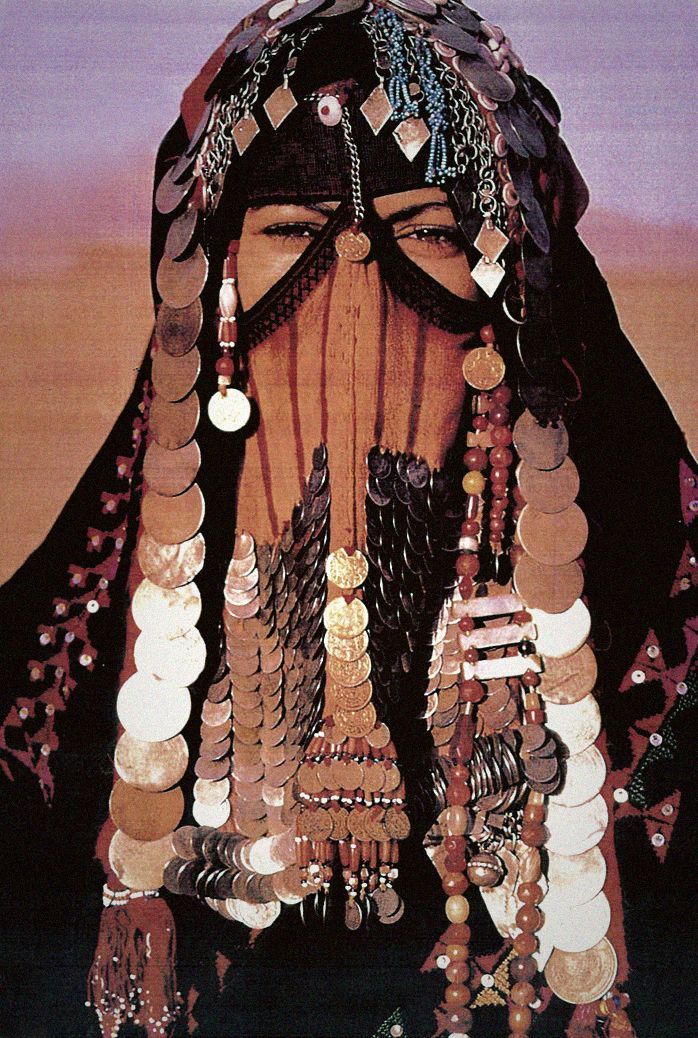

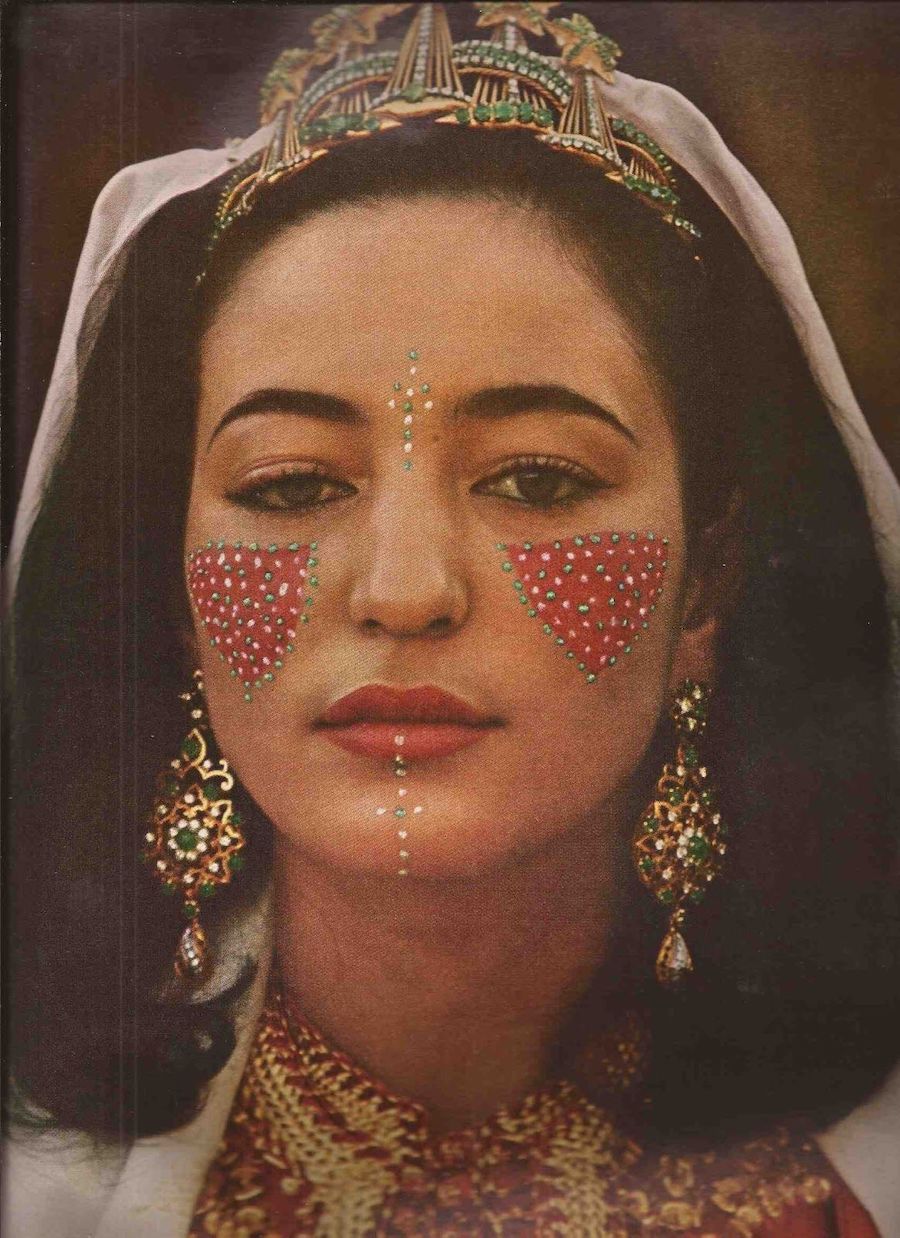

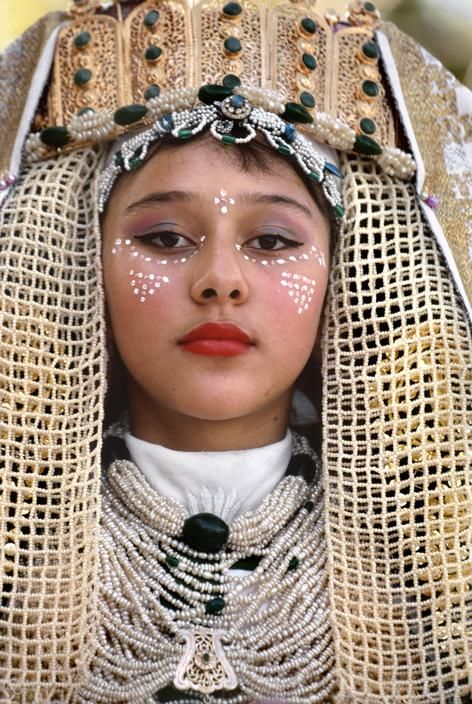

Morroccan and Bedouin Traditions

The Bedouin or “desert dwellers” are a nomadic, Arab people based primarily around North Africa and the Middle East who either follow Christianity or Islam. Depending on which area you’re in, the extent of veiling varies (i.e. Levant women are pretty much uncovered). In other cases though, burqas become increasingly bedecked for in coins and beads for special occasions like weddings. Meanwhile, over in Morocco, there’s a little face painting tradition that’s not quite as intense as Bulgarian gelena, but still striking: dots along the cheeks.

Japanese Brides

More understated than the rest of our looks, but no less striking. The traditional Shinto outfit for Japanese brides is a minimalist’s dream, as is the traditional wedding ceremony that accompanies it. There’s no best man, and no maid of honour. Just three cups of sake and some outfit changes – our favourite of which is the shiromuku, a kimono with a wonderfully graphic, voluminous silhouette:

Historically, it was reserved for the samurai class (who were no strangers to swag). The white represented not only purity, but the power of the sun – which may explain the circular shape of the headpiece, which acts as a clever hair veil of sorts. Any designs on the dress will also be minimal, usually of delicate foliage, traditional symbols or cranes (which mate together for life).

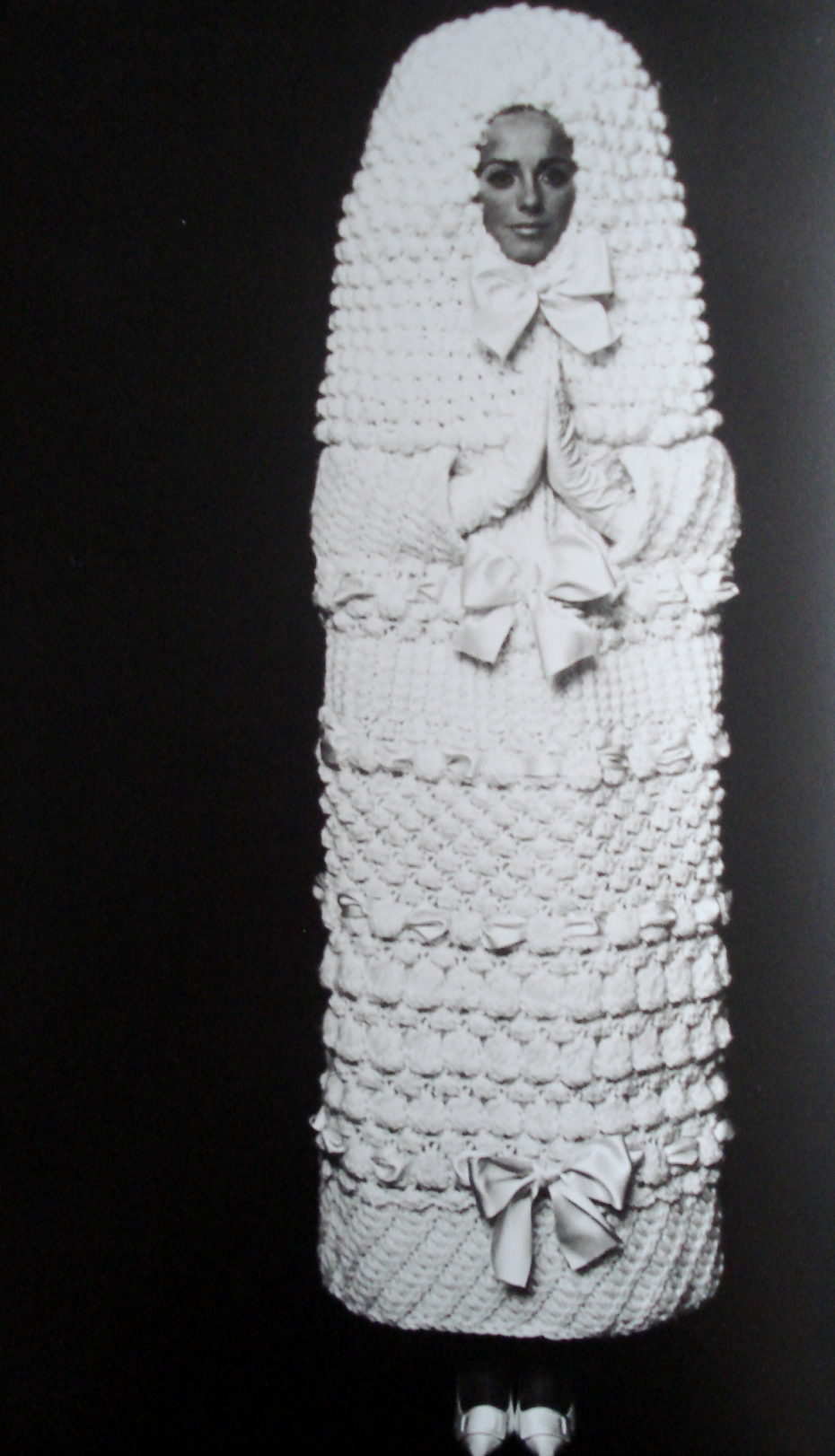

And then of course there’s Planet Fashion…

Long, short, or cocooned in a plushy knitted dream – there’s nothing that won’t walk down the runway these days. From about the mid 20th century on, the modern bridal gown has become a feast of texture and deconstructed materials, capable of layering Surrealist, technological, and traditional folkloric elements (here’s looking at you, Christian Lacroix) to create a gown that tells a rich story. As Lacroix himself said, “For me, elegance is not to pass unnoticed but to get to the very soul of what one is.”