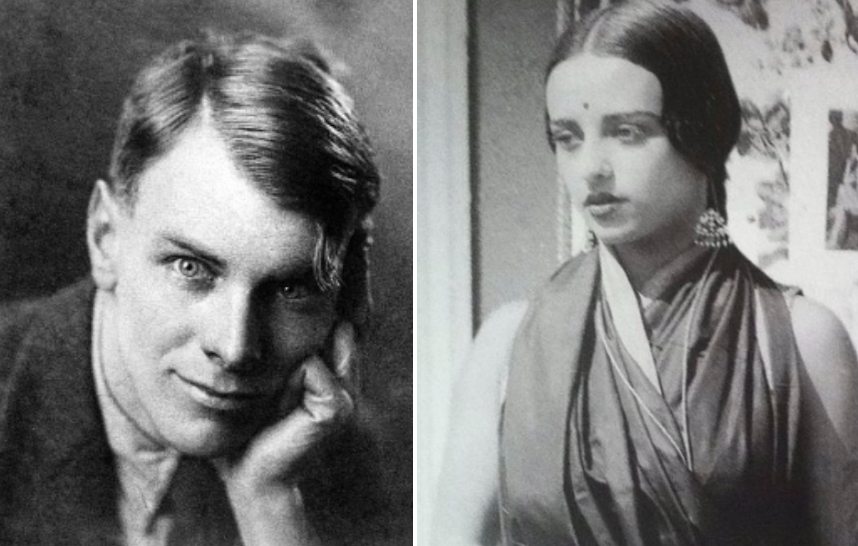

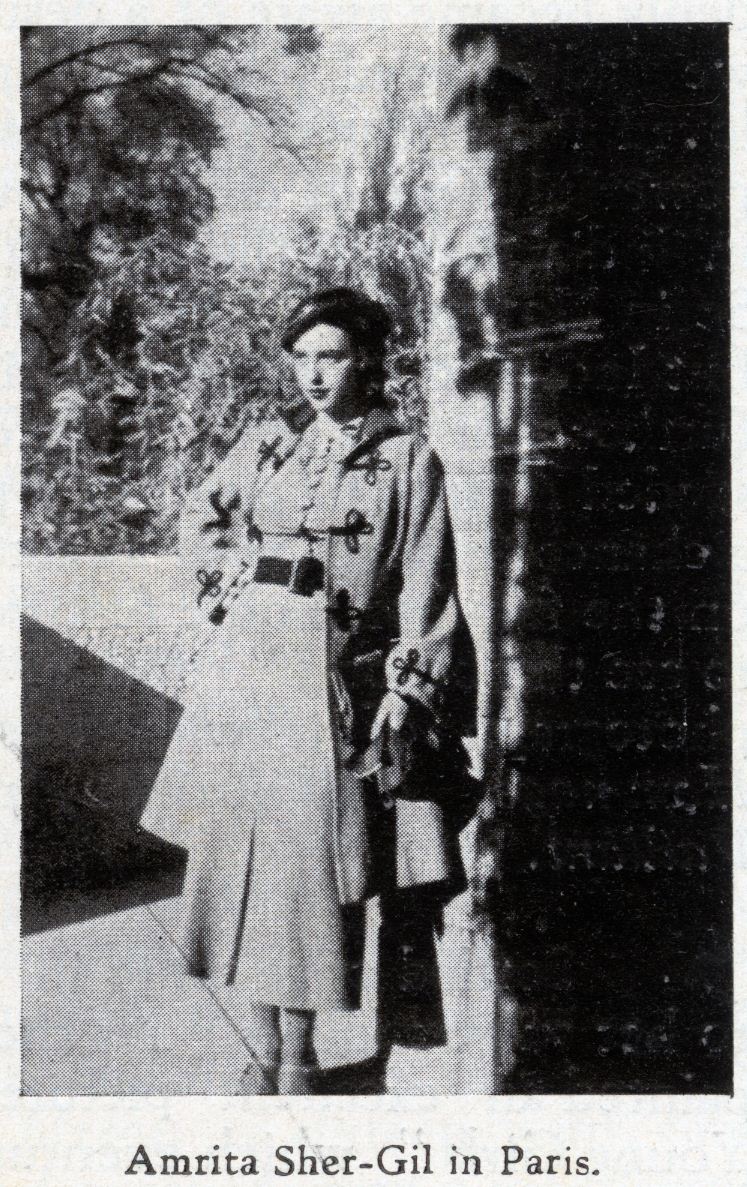

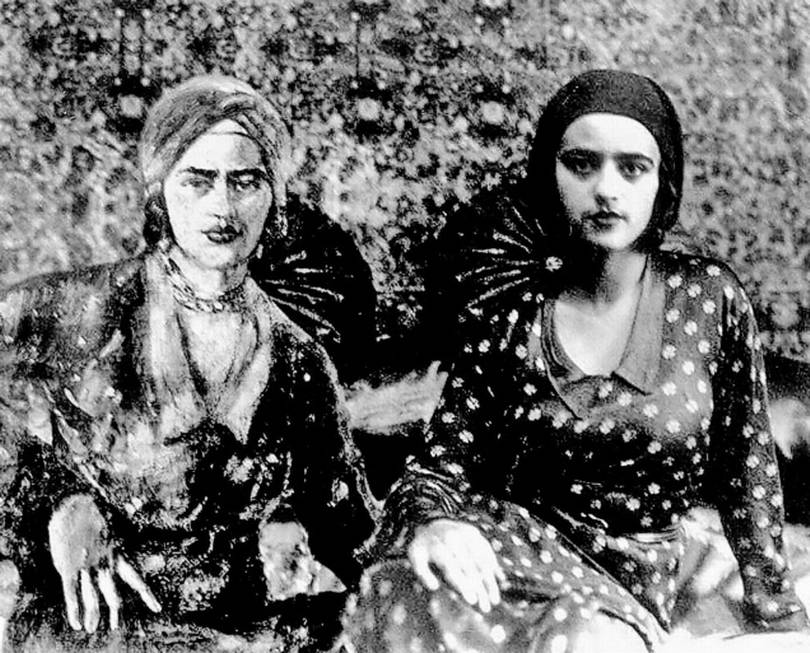

The bold red lip. The dark, enigmatic brows. Leaning up against the wall with her hair braided tight, the young woman looked every bit like Frida Kahlo, posing for a shot with her photographer-lover. She was also an artist – albeit, comparatively unsung – in her own right. Meet Amrita Sher-Gil, India’s answer to Frida’s creative vibration, who brought Modernism in art to the subcontinent. And if we invite comparisons to Frida (those brows), it’s not to diminish her own legacy, but rather, to further embed her into a sisterhood of self-liberating, female artists to follow…

“Europe belongs to Picasso, Matisse, Braque…. India belongs only to me”

Amrita Sher-Gil

Amrita was born and raised partially in Budapest, Hungary, and Shimla, India. Thus, she grew up with one foot in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and the other in what was then British India (present day Pakistan). Born with a firm place in upper-crust society, her mother was a bourgeoise, Hungarian opera singer (named Marie Antoinette, no less) who met her father, Umrao Singh, whilst on holiday with her friend Princess Bamba Sutherland in India. Amrita’s father was a Sikh Punjabi aristocrat, so she and her younger sister grew up in very intellectual and multilingual households, exchanging ideas in English or French one moment and Hungarian the next. Perhaps that’s where she gained the confidence to declare herself an atheist at a convent school by the age of nine and get herself expelled.

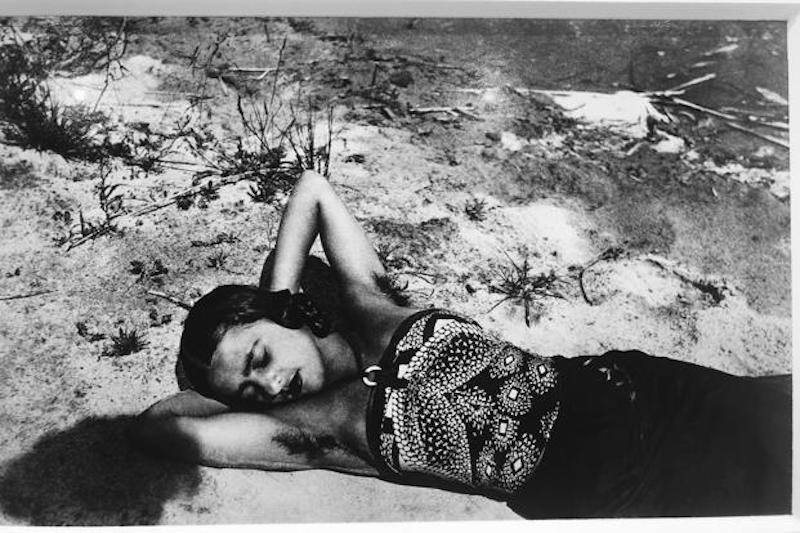

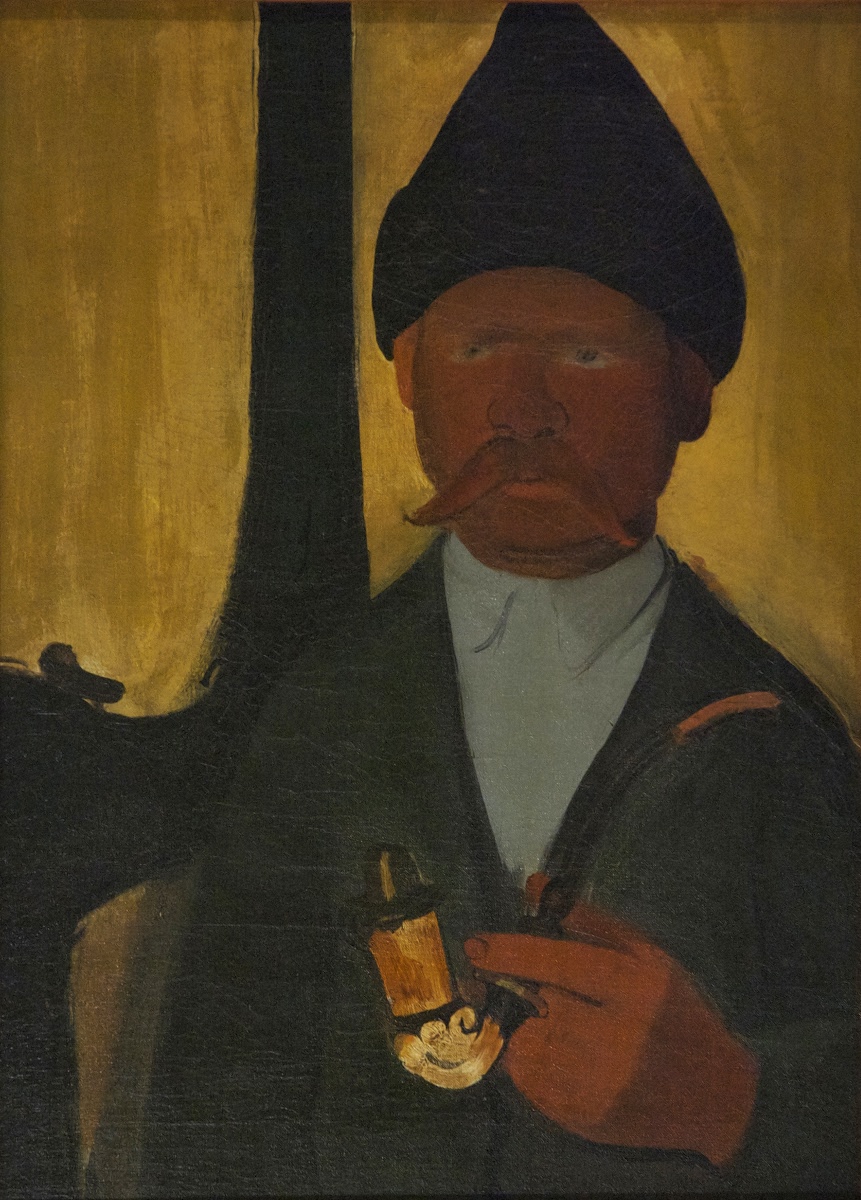

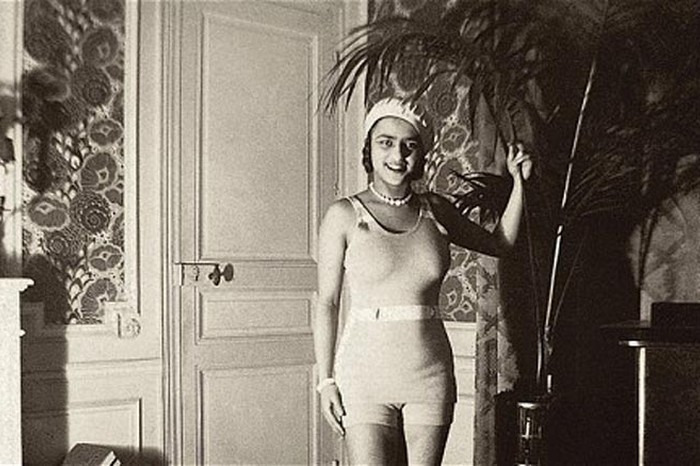

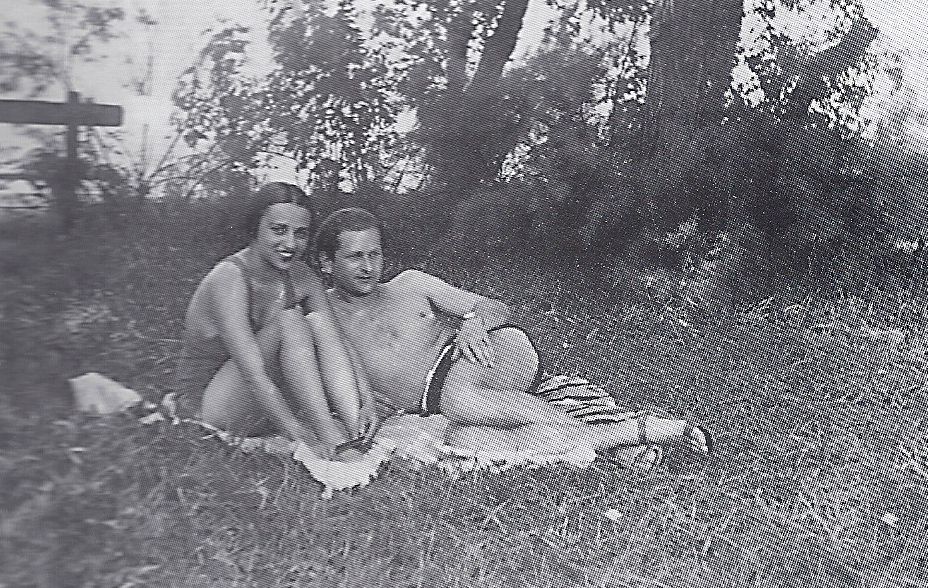

Amrita’s family was also passionate about the arts, what with her mother’s connections to the music world and her father’s impressive knack for photography. Perhaps that’s why he was closest with the fiery little Amrita – they both shared a passion for visual expression. We’re rather lucky, actually, because his photos of Amrita capture her individuality (and serious sartorial swagger) from a very young age:

One of the biggest differences between Frida and Amrita, however, is that the latter grew up in a very gilded world. Frida’s family wasn’t impoverished, but they were bogged down with medical bills for her operations and had to hustle to make ends meet. Amrita, on the other hand, came from a very wealthy family with access to the finest tutors and latest technologies (ex. her dad’s photography hobby), and the material benefits that British colonialism provided for the upper echelons of society.

Despite these differences, both women empathised with communist and socialist ideals, and often hoped to represent local craftspeople and blue collar workers in their own artistic legacy.

Amrita’s been called “a communist wolf in British clothing,” and had a brief but passionate relationship with the journalist and longtime communist-sympathiser Thomas Malcolm Muggeridge, who later said that “the best thing that ever happened to me in my Statesman (a paper he worked for) days was meeting Amrita.” She was passionate, and uncompromising in everything she did.

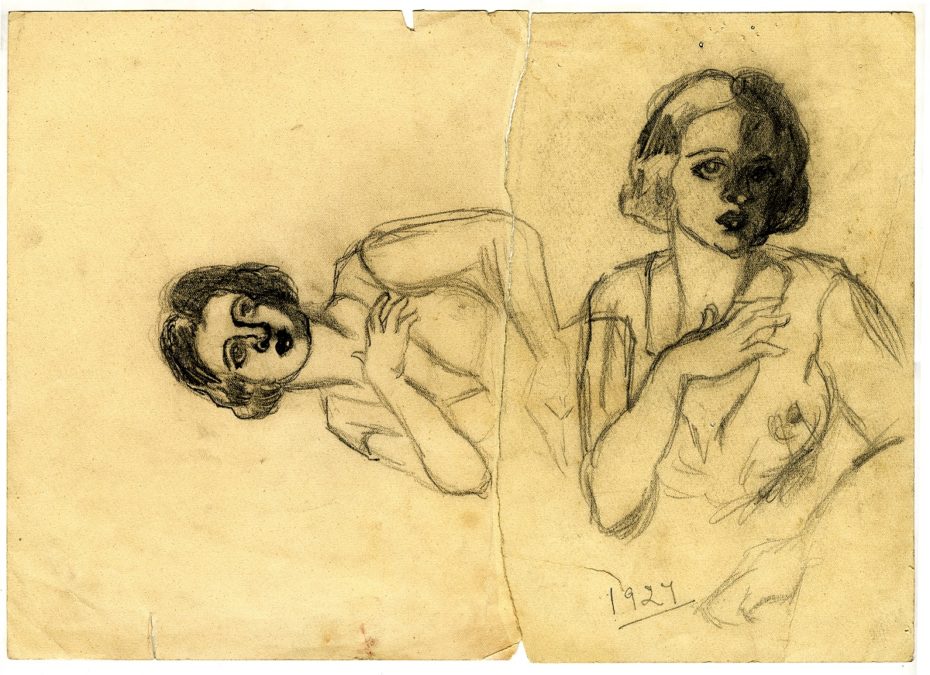

It was clear that Amrita, who had already started sketching the family’s household staff, was destined for a future in the arts. So she did the best thing a girl can at 16-years-old, and moved to Paris.

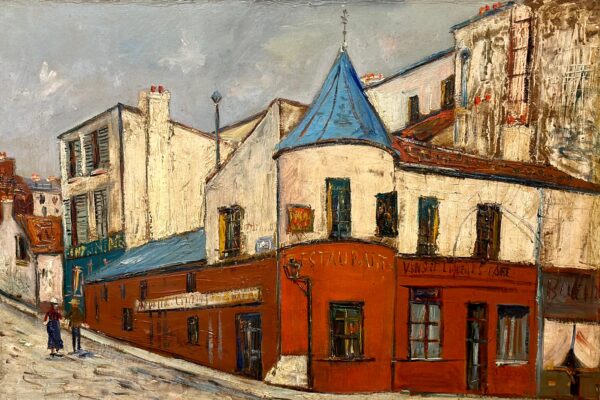

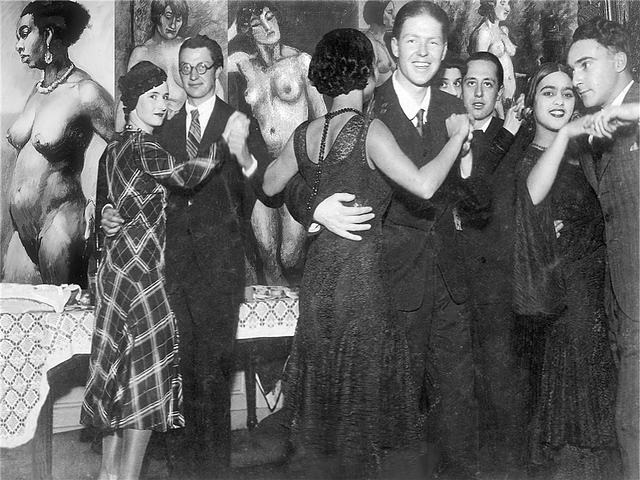

There, she studied at the prestigious Académie de la Grande Chaumière, where Picasso, Manet and Cezanne painted, as well as the Ecole des Beaux-Arts – both terribly fun places to grow not only as an artist, but as a creative minded young woman. This wasn’t just Paris. It was the Roaring Twenties in Paris…

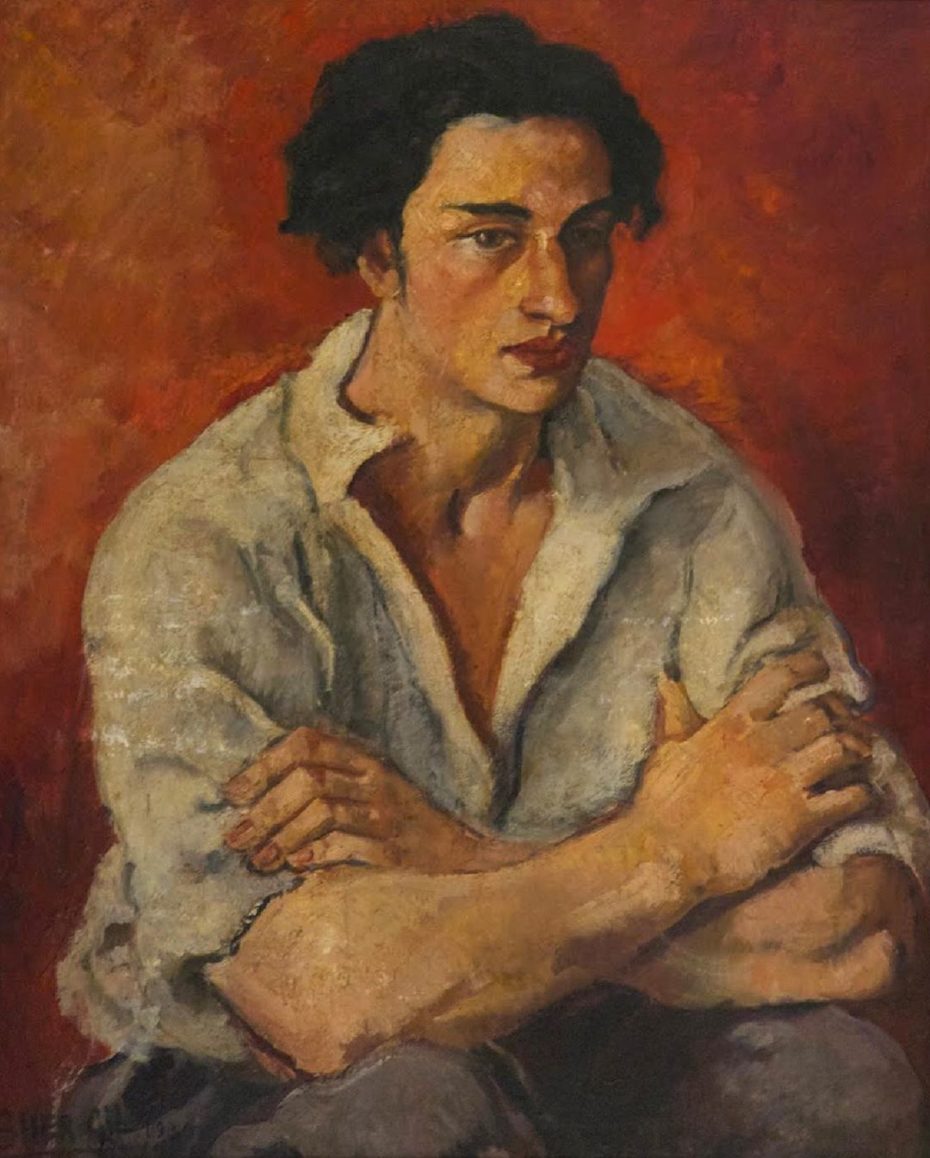

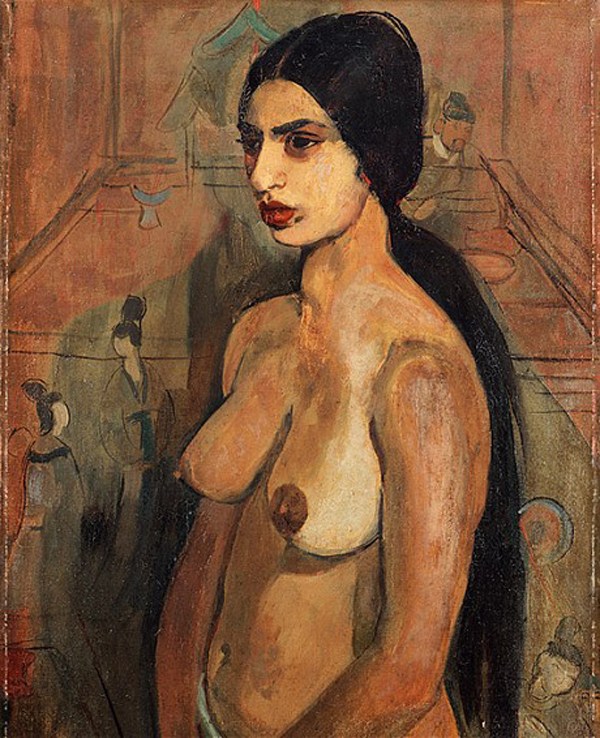

Amrita started to experiment – with colour, with technique, and with love. One of her rumoured lovers was Marie-Louise Chassany, a fellow student at the Beaux-Arts. It’s said that many of Amrita’s romantic partners figured in her portraits, and Marie-Louise had three to her name.

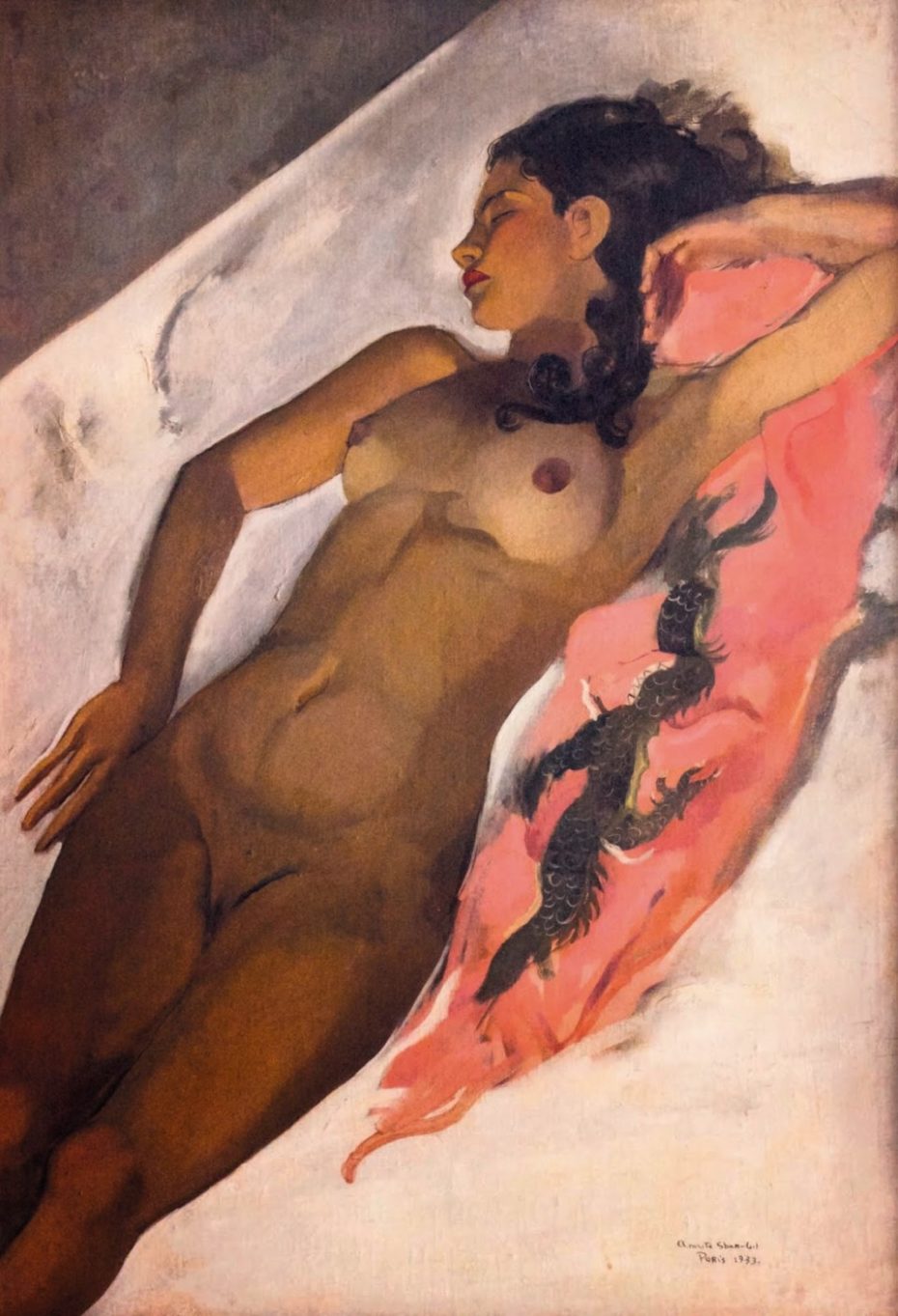

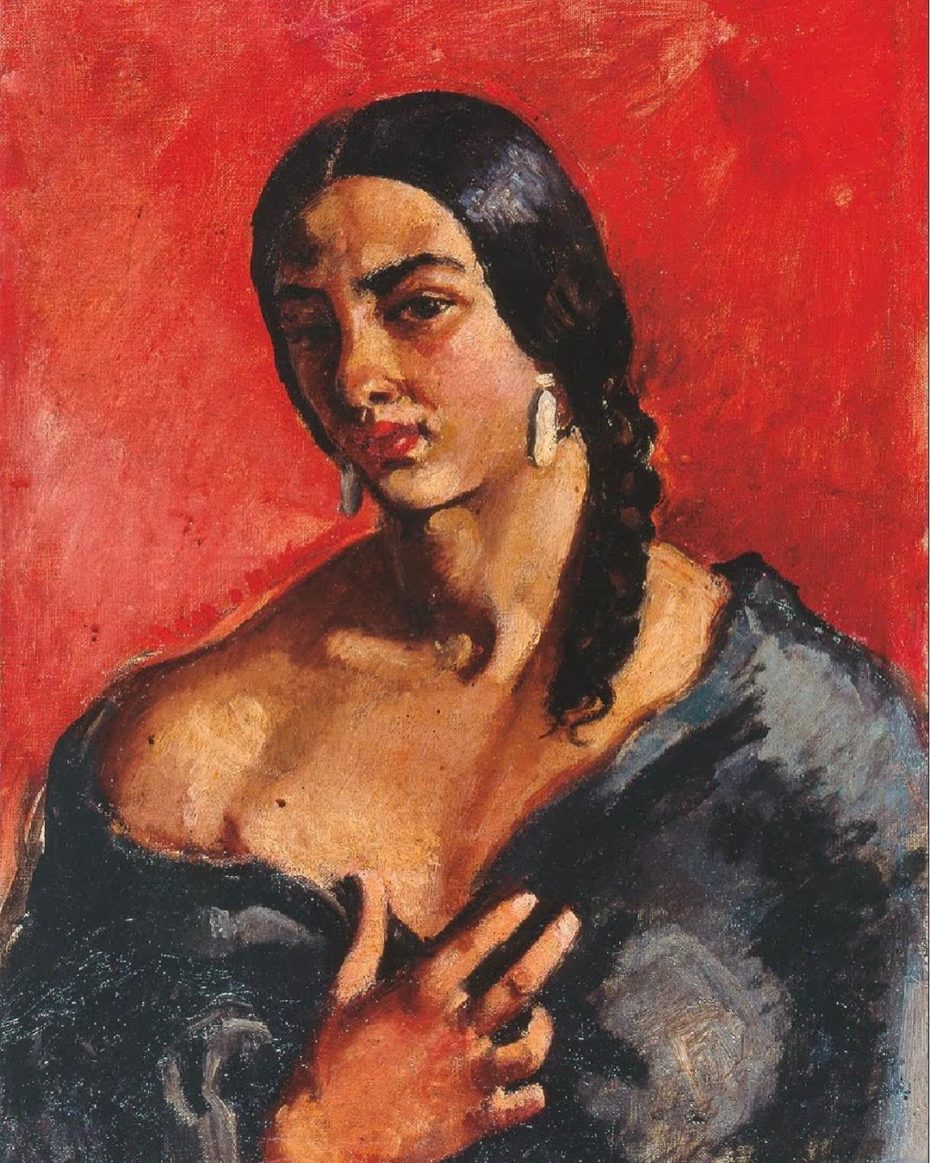

But let’s talk style: there are touches of Cézanne’s scandalous, floating fruit in Amrita’s own still lifes. There are colour and compositional influences of Picasso, Braques, and above all, Gauguin in her portraits and scenes of public life.

There’s none of Frida’s surrealism, but there are often tonal undercurrents running a shade darker in her work. It’s not quite ominous, but it does feel as if we’re pulling back the curtain on something (or someone); that we’re getting the glimpse of Paris’ underbelly. Consider her painting of Notre Dame, in which the focus is one blackened spiral, quietly standing watch in a corner.

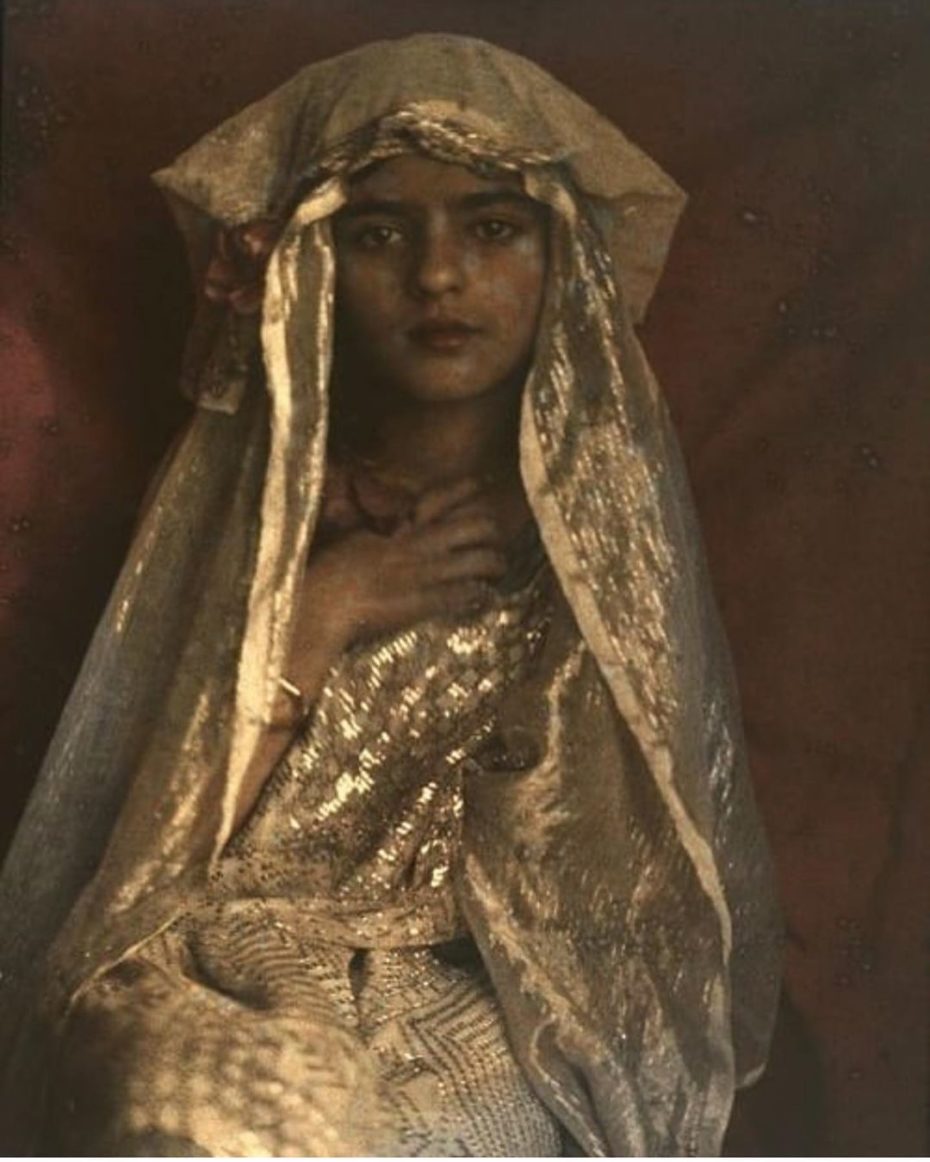

Amrita’s work was some of the best at the Beaux-Arts, and her painting Young Girls (1932) earned her both a gold medal, and a spot as an associate of Paris’ 1933 Grand Salon. It would’ve been impressive for anyone her age, but it was particularly epic considering her gender and ethnic background. Amrita was the toast of the town, and her piercing self-portraits became one of her staples.

Also, can we talk about her fashion sense for a minute here? It’s secondary to her work of course, but it’s still so fiercely chic and, in that sense, an extension of her creative self…

Just as Amrita was taking off in Paris, one of her teachers suggested that she move back to her beloved India where she’d be more “in her element” to paint the subjects and culture she so admired. It might sound like xenophobic sabotage masked as career advice, but Amrita did think her teacher made an interesting point: there was room to do something different in India. “I can only paint in India,” she wrote, “Europe belongs to Picasso, Matisse, Braque…. India belongs only to me”. In 1934, she moved to back to Shimla, India.

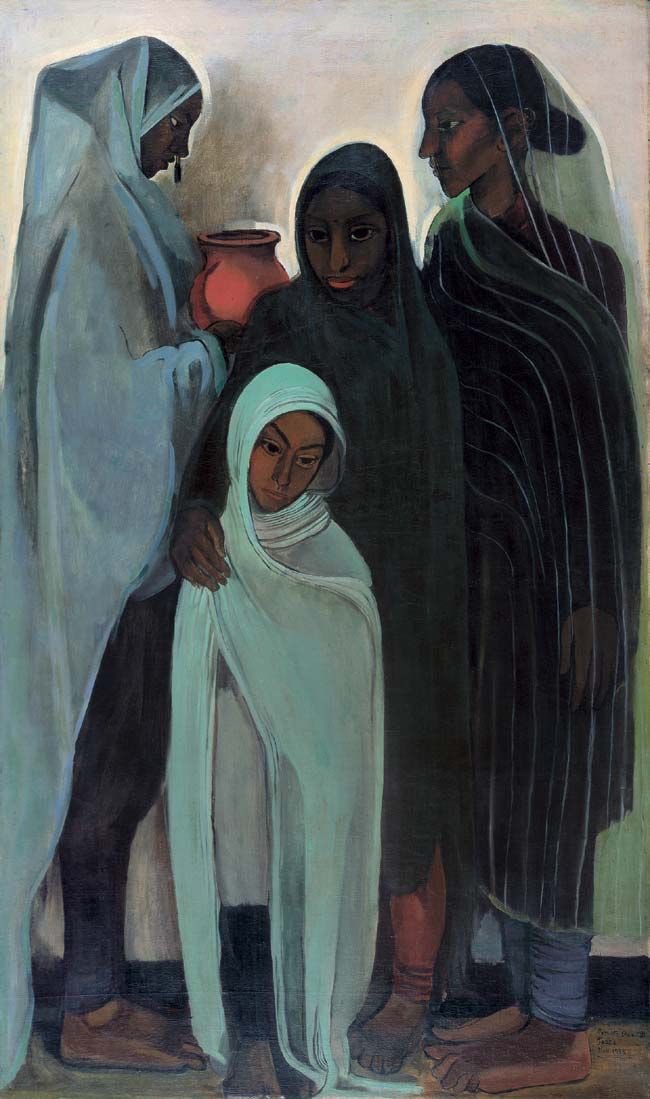

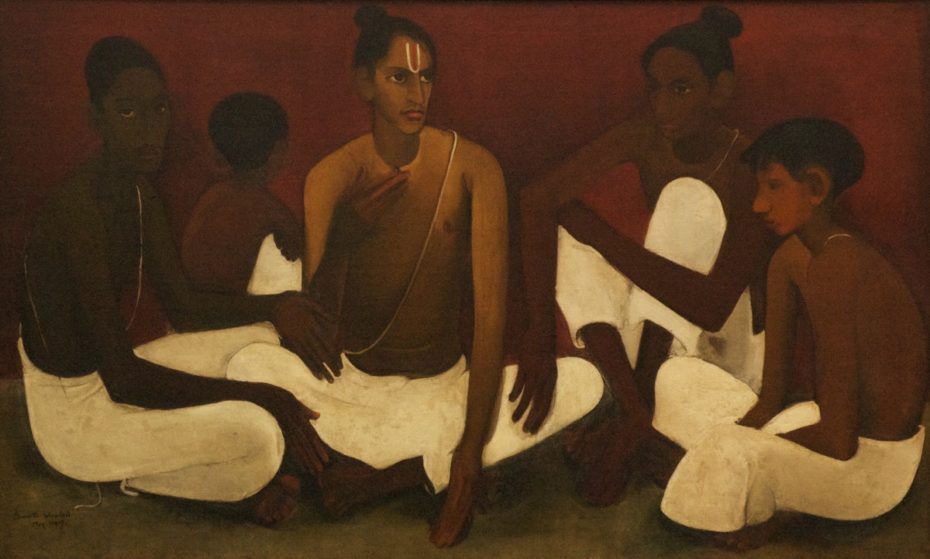

Amrita decided it was her duty to represent everyday people, doing their everyday tasks. Travels around South India led to the creation of empathetic works like South Indian Villagers Going to Market (1937), and Hill Women (1935). To this day, a look back on Amrita’s “Indian period” offers something that few other artists did: depictions of Indian women, by an Indian woman.

In fact, she became so popular in India rumours started swirling about a romantic relationship with the man who would become India’s first Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru. As a public voice for the working class – despite her rather bourgeois upbringing – Nehru was fascinated with Amrita. It’s on-record that he visited her in Gorakhpur in 1940 (as well as several times during her exhibit in Lahore in 1937), and that her paintings were being considered for use in the Congress propaganda for village reconstruction (ex. her painting, Three Bullock Carts)

Unfortunately, her family burned her correspondence with Nehru, given she was married to her Hungarian first cousin, Dr. Victor Egan. Not even one Nehru portrait was squeezed out of their friendship. She said he would’ve been “too good looking’ to paint.

Amrita and her husband, Victor, decided to move to the artistically vibrant city of Lahore (present-day Pakistan). There, they lived at 23 Ganga Ram Mansions, The Mall. Amrita’s studio was on the top floor of the townhouse, and she was just prepping for her next major one-woman show in town when the unthinkable happened. Amrita fell ill – so ill, that she fell into a coma. A few days later, at just 28-years-old, she passed away in December, 1941.

To this day, there’s a lot of mystery around Amrita’s death. Some historians believe she could have died from a failed abortion, or tuberculosis. Others suspect foul play, as Amrita continued to have affairs right up until her death. Her own mother, for example, believed that the jealous Victor – who would’ve had ample access to harmful substances as a doctor – killed her daughter. The mind reels.

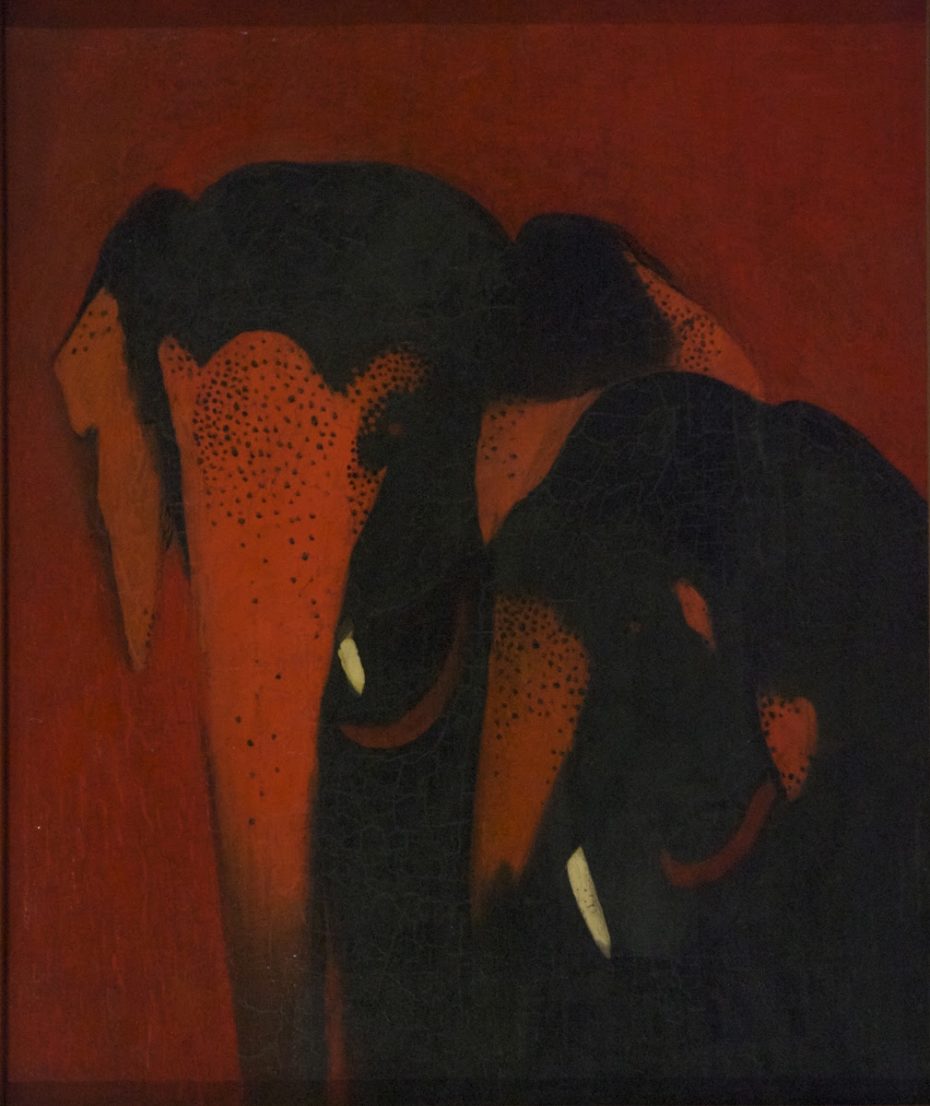

Scandals aside, Amrita left behind a legacy of some 200 paintings (many of them are on display at the Modern Art Gallery in New Dehli). The last painting she ever did was made from her balcony in Lahore:

“She saw a milkman with his buffaloes, and did her last unfinished painting,” writes biographer Yashodhara Dalmia in Amrita Sher-Gil: A Life, these “slate black buffaloes squat on the ochre road, one with a crow perched on its snout.” It was ordinary, and utterly breathtaking. It was the perfect, albeit tragic love letter to the country she loved.