It was a time when divorcées were only allowed to be buried at night, when the Arch of Triomphe wore a black mourning veil, and the business of death was booming in Paris. In fact, over one thousand undertakers worked together in their own veritable mini-city at the town’s edge, from coffin makers and casket upholsters to carriage builders and stablehands for horse-drawn hearses of the day. The 35,000m² space at of “104 rue d’Aubervilliers” was a Parisian mecca for funeral planning, and today, its storied address invokes quite a different energy from its time as “the Grief Factory,” as 19th century journalists called it. Today, “Le 104” (or “CentQuatre”) has been converted into a community centre for all walks of life; on any given day you’ll find ballerinas and breakdancers, experimental film festivals and daring art exhibits. It’s our little known address du jour for tourists and locals alike. So let’s take a stroll through its many reincarnations…

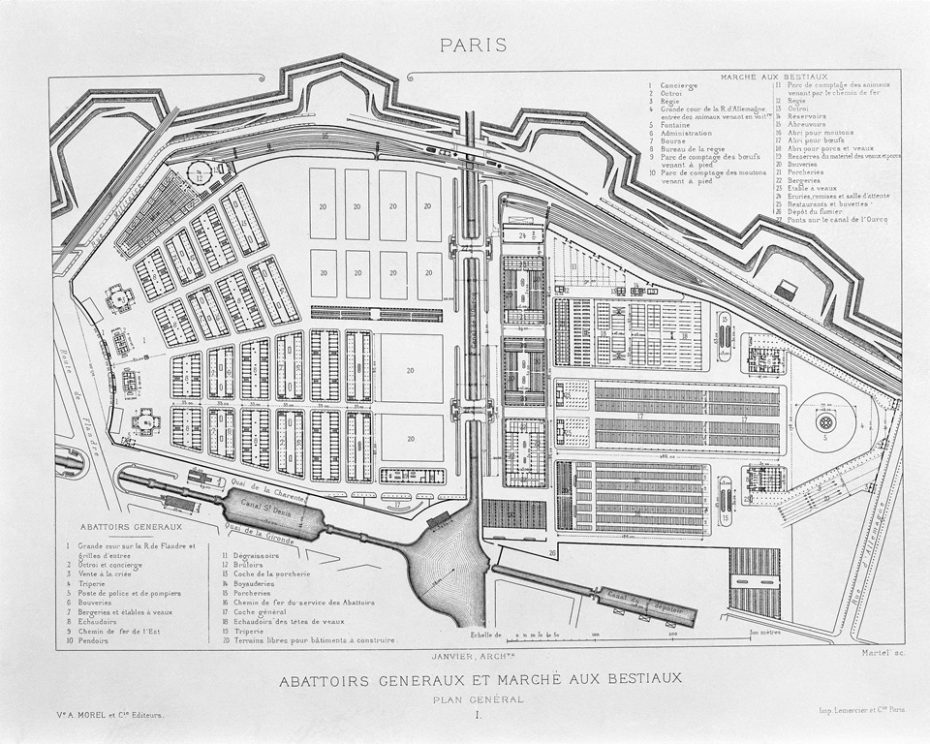

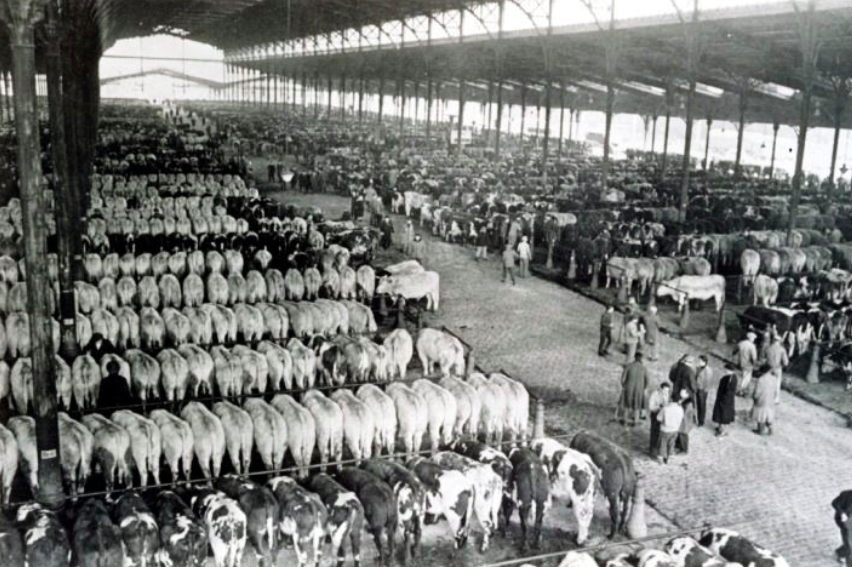

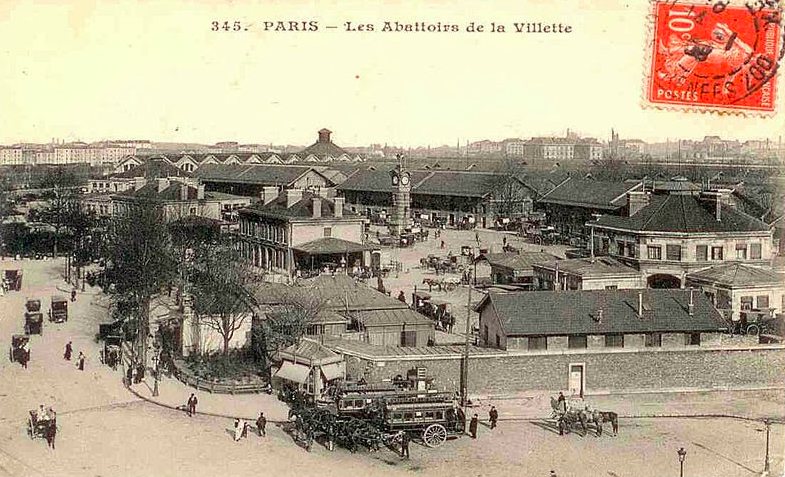

The first thing to know about the 104 is that it’s big. Really big. Big enough to house Paris’ bustling meat industry, which it initially did throughout the early 1800s before becoming a one-stop-funeral-shop.

Its location in the 19th arrondissement, effectively the outskirts of Paris at the time, was prime real estate for sprawling slaughterhouses. They were designed by the rather hip architect, Paul-Eugène Lequeux, and opened in 1849.

In 1873 the massive abattoirs (slaughterhouses) were bought out by the long-syndicated Pompes Funèbres (undertakers) who decided to make it even bigger. So they added two more halls separated by a giant courtyard, and fit over 1,000 employees inside the premises. They turned out over 150 funeral processions a day.

The subterranean level was accessed by two huge ramps, and was home to some 300 horses in over two-dozen stables. It’s the first thing you see when you step through the doors of Le 104 today, along with little reminders of its equestrian past.

The ground floor contained 100 funeral chariots, 80 hearses, and 6,000 coffins. On the periphery of the ground floor there were also public workshops and stores that specialised in funeral painting, ornament making, tapestry, and other crafts.

It was a veritable Parisian micro city powered by the business of death.

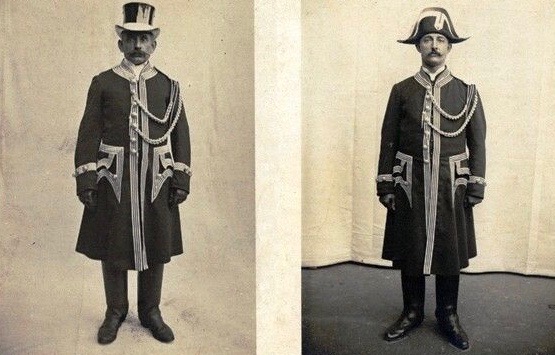

In the 1880s, French funerals were still a strictly religious affair with a lot of highly curated pomp. Thus, they were treated with all the grandiosity you’d expect from the Catholic church; every detail of a procession was outfitted with the finest craftsmanship, from carriage to the coffin bearer’s lapels, which is why the 104 was so lucrative.

That all changed with Victor Hugo. The Les Miserables author shook things up when he died in 1885 by refusing a religious procession in his will. “I leave 50,000 francs for the poor,” he wrote, “I want to be buried in their hearse, and refuse a church oration for my funeral. I beg a prayer to all souls. I believe in God.”

His beloved Parisians went all out, and the press reported that between one to two million people followed the procession in the coming days. The Arc de Triomph was draped in black gauze, and schools were closed. Thousands of flowers were offered at the feet of the Pantheon.

Still, Hugo’s funeral was an anomaly for its time. It wasn’t until the 1905 Separation of Church and State that things began to change on a larger scale and the funeral industry started loosening its collar. Before this time, divorcées could only legally be buried after dark; those who died by suicide were refused a proper burial entirely. The 104 still continued to flourish however, even if by 1928 it was filled with more automobiles (chiefly, Renault and Citroën) than horses.

Come 1987, the funeral monopoly had disintegrated. Private organisations popped up with their own teams and goods, and the 104’s massive operation couldn’t really sustain itself. In 1997, it closed its doors for good – or so the city thought…

In 2003, the city hired cutting edge architectural firm Atelier Novembre to breathe new life into the space as a cultural centre. Since opening in 2008, it has become one of the most unexpected pulse points of the city; a place where rebellious teens and families alike come to dance, play, eat and shop, unaware of its fascinating past.

Today, the ground-level portion of the 104 is dedicated to an equally lively centre of commerce. The space unites the two massive buildings separated by a courtyard, with one that lets you out on Rue Curial, and the other Rue Aubervilliers. The latter has a cute little open-air cafe called Le Café Caché (The Hidden Cafe) with a retro style photo-booth.

The first building boasts a charity vintage shop (or “Emmaüs”), bookstore, and an art gallery called B’ZZ, which says it focuses on displaying “emerging, aspiring, and brut artists” who often recycle found objects or “junk” in their work. There’s even a restaurant called Le Grand Central, and an organic market on Saturdays.

The eclecticism of the centre owes its diversity, in part, to the fact that the funeral industry was at its peak in the 19th and early 20th century in Paris. We can thank the undertakers’ needs for all those little impasses, courtyards and stables that make for such a dynamic space for our eyes today – one that draws you in off the street with dozens upon dozens of neon “Welcome” signs in various languages, and beckons you into different alcoves…

The real standout, though, is its rotation of cultural events; it’s welcomed a circus and “sound festival” and countless art installations.

It’s places like the “CentQuatre” that get us wondering about the layers of our urban history – what other stories are we missing in places we walk past every day? Even in Paris, a city that proudly wears its history on its sleeve, there are buildings whose past goes unspoken for. We’ve seen many a repurposed warehouse and factory in our time, but it’s the way in which le 104 has left such proud, visible relics of its “deathly” past – from the markings of old horse stables, to its still glowing, interior street lamps – that so beautifully marries it to a new, equally unique present. It goes to show what happens when we decide to nourish our cultural history as a living, breathing narrative.

Check out what’s on the calendar for the coming months at the CentQuatre on their website.