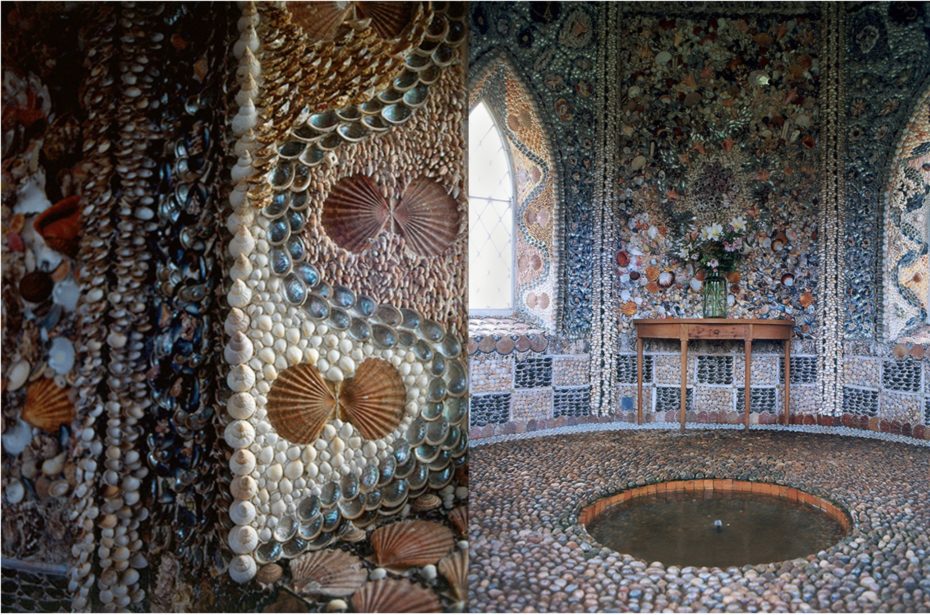

In Margate, on the south-east coast of England, there is an underground grotto lined with majestic mosaics made entirely of seashells – and no-one knows how it got there. The site was discovered in 1835 by a father and son who were attempting to dig a duck pond. The story goes that the young boy was lowered into a hole that revealed itself during their excavation and, naturally, he found himself in a subterranean labyrinth decorated with 4.6 million individual shells arranged in intricate patterns over an area covering 2000 square feet. The boy’s father, James Newlove, ever the entrepreneur, opened the site to the public in 1838 and the legend of the Margate Shell Grotto was born.

Mystery shrouds the Margate grotto – as well as millions of shells. There are no records pointing to the cave’s construction, but there are many theories about it, each one politely pooh-poohed on the site’s official website. A lack of accessible escape routes quashes the smuggler’s cove theory. The fact that it was built underground suggests it wasn’t a deliberate display of wealth.

The current owner believes it to have a spiritual quality, and she’s not the first: the archives are full of images of turn-of-the-century seances taking place there. There is even some speculation that it could have been the site of pagan worship – Mr Newlove turned out to be quite the savvy marketing man, who likely knew how to get the rumour mill going and draw a crowd.

The fact is, in the 19th century, shellcraft was at its peak.

The gardens of stately homes across Europe were suddenly incomplete without a grotto lined with mosaics of local and exotic shells. Neither was your relationship with a sea captain official until you’d been presented with a shell-encrusted box – a gift so popular in the 1800s that it officially became known as a “Sailor’s Valentine”. Even among the aristocracy, there was no greater declaration of love than gluing several thousand shells to something – just as Louis XVI did to the walls of the Grotto of Thetis to flirt with Marie Antoinette.

While seashells have been a reliable source of decoration throughout the ages and around the world, the European mosaic craze was distinctly different – and few embraced it so passionately as the British.

The first recorded shell grotto in the UK was commissioned by King James I in 1624 for the undercroft (a posh word for a variety of underground rooms) of Banqueting House, in London. Despite its humble name, the “house” was where generations of monarchs would entertain their guests and, notably, was heavily influenced by Italian architectural details – from the Classical to the Baroque.

King James’ chintzy Italy influenced drinking den laid the foundations – as it were – for the trend among the British upper classes. However, a century later, it was Alexander Pope’s underground writing retreat that became the ultimate It-grotto. Planning out your premises became more than a hobby, it was a sport: “mine’s prettier than Mr Pope’s” claimed one especially ambitious Lady of her grotto, in 1736.

In his own words, the poet described the interior of his dazzling dwelling as being “finished with shells interspersed with pieces of looking-glass in angular forms… when a lamp is hung in the middle, a thousand pointed rays glitter and are reflected over the place”. We’d argue Alexander Pope might have claim as the inventor of the disco ball.

Pope’s convenient riverside address attracted boatfuls of visitors, who in turn were inspired to begin working on their own follies, which cost hundreds of thousands of pounds and took decades to complete. Pope’s passion project was still in progress at the time of his death.

With competitive shellcraft raging among self-described “conchologists”, shipments for exotic overseas shells was at an all-time high. An influx of shell shops opened up, especially in the capital. One such boutique was owned by Marcus Samuel, an antiques seller, who expanded his trade in 1830 to include imported shells from the Far East, which became the beginnings of an oil empire, known today as Shell.

Another honourable mention is The Little Chapel in Guernsey, which was built in the early 1900s by the French monk Brother Antoine Déodat. His vision was to build a miniature version of Lourdes basilica.

The first iteration was so mocked by other monks that he destroyed it almost as soon as he’d finished it. His second try stood for nearly a decade, until the Bishop of Portsmouth tried to visit and was unable to fit through the door. Again, Brother Déodat tore it down and started from scratch. Like Goldilocks before him, his third try was just right. Today, The Little Chapel is one of the Channel Islands’ best-loved monuments, decorated in – you guessed it – shells! As well as pebbles and broken bits of china, giving it a technicolour finish.

Just as every tide rises and falls, bringing with it new treasures from the deep, so too has the popularity of shellcraft – in particular, shell-covered follies of various forms.

Consider yourself lucky to be living through the re-re-re-renaissance of the shell grotto, with 21st-century examples sprouting once more in the gardens of the British well-to-do as maximalism makes its comeback to interior design.

Grotto restorations have been taking place up and down the country, such as the one on the grounds of the Grade I-listed Endsleigh Hotel in Devon and the Cilwendeg Shell House Hermitage in Wales. So in 2019, who’s in the business of shell art?

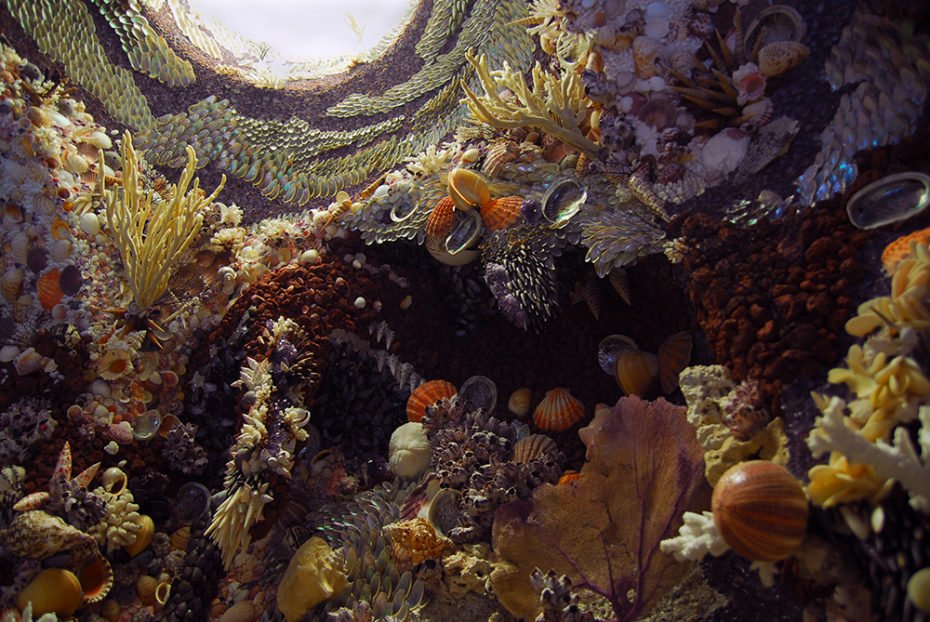

As you might have guessed, there aren’t many, but if there’s one name to know, it’s Blott Kerr-Wilson. The British artist has been travelling around the world creating bespoke shell houses, grottoes and individual pieces for collectors ever since she first covered her bathroom flat in Peckham with shells and won an interior design award for it.

Her portofolio of work is enough to convince you that you should probably spend the weekend collecting shells from the seashore.