No kings. No priests. No aristocracies. Only a society whose residents believed they should “grow together — not by competition, but by united action.” It may sound like a Bob Dylan lyric, but it’s a 104-yr-old excerpt from Herland, the science fiction novel by suffragist Charlotte Perkins Gillman in which a money free, farming heavy, all-female utopia thrives in South America. And as wild as it must’ve been for a petticoated society to read about naked, self-sufficient women swinging from the vines, the book wasn’t that far fetched in terms of what was actually happening in turn-of-the-century America. Communes were everywhere. Some turned into sinister cults. But others were just vegetarian, fruit-loving societal dropouts who pioneered environmentally and socially progressive ways of living. And frankly in these times, some of them might deserve a second chance …

Fruitlands

We can’t talk about early American communes without talking about the Romantic Era, which was basically the Swinging Sixties of the 19th century. As Western society industrialised, the “Romantics” yearned for a return to a more sensitive, pastoral society. One of its offshoots was Transcendentalism, which called for subjectivity over what they saw as a dogmatic, rising empiricism. Pioneers included Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau, the author of Walden (1854), and its message was all about feeling your oats in nature, of letting the heart transcend the head – and it was partially thanks to that message that a weird little commune called “Fruitlands” was born in Harvard, Massachusetts, circa 1840…

Fruitlands was the dream of writer-philosopher-reformers Amos Bronson Alcott and Charles Lane. Never mind that in the beginning, there were only about ten fruit trees on their 90-acre plot. Between Alcott and Lane, Fruitlands attracted some 14 followers who were intrigued by their speeches of finding peace through a life of “simplicity in diet, plain garments, pure bathing, [and] unsullied dwellings.” Eventually, they succeeded in planting 8 acres of grains, vegetables, and melons for sustenance.

It was very important for Fruitlands to remain isolated from the rest of the “corrupt” world, which was its first mistake in failing to thrive. Adjacent communes, like the über creepy Oneida Colony, understood that you either needed 1. a really rich relative or 2. a mainstream side hustle (i.e. making silverware) to stay afloat – but Alcott and Lane just didn’t wanna sell out.

There’s a lot to love about Fruitlands. Namely, the vegetarianism (did you know it takes 441 gallons of water to make one pound of beef?), the whole #NatureLife aesthetic, and their feminist leanings – but at the end of the day, Alcott and Lacon were what you might call, killjoys. Residents had to go fully vegan, only drink water, only bathe in unheated water, and avoid any “artificial light” (i.e. candles) lest such artificialness should “prolong dark hours or cost them the brightness of morning.” Interestingly enough, Ralph Waldo Emerson himself came out to visit and see what the fuss was about. And he wasn’t impressed. “I will not prejudge them successful,” he wrote, “They look well in July. We will see them in December.” Sure enough, seven months in the commune members disbanded for meatier pastures.

You can still visit the old Fruitlands estate today, and read Alcott’s daughter’s book, Transcendental Wild Oats, to get all the dirt on the commune.

Octagon City

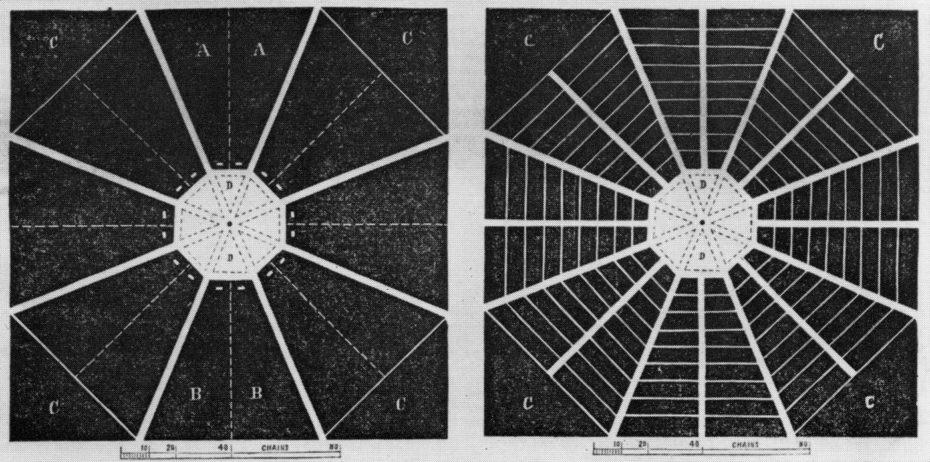

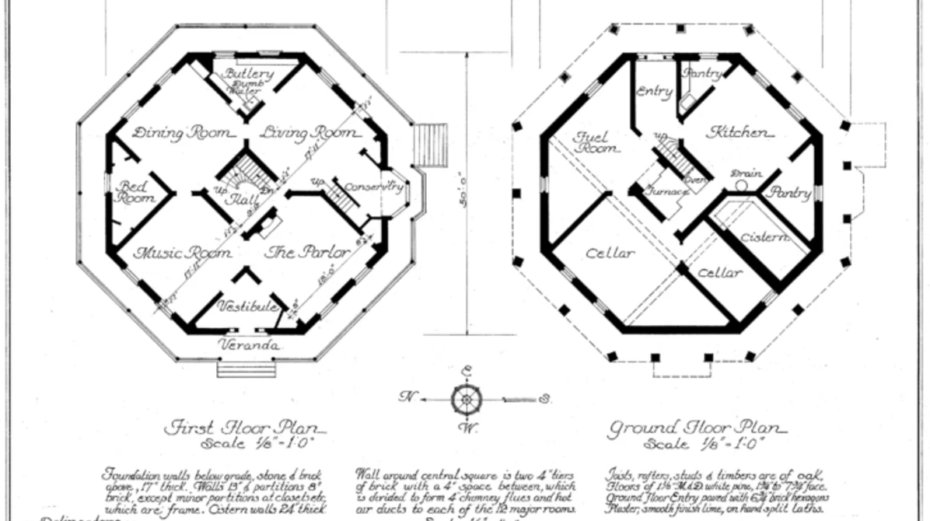

All roads led to Octagon City – at least, that was the plan. Founded in Allen County, Kansas in 1856, the experimental community was meant to set the precedent for socially and ecologically moral living in America. It was the dream of an abolitionist, vegetarian activist named Henry Clubb, who basically read a whole bunch of literature on the benefits of plant-based diets, and, of course, octagons as a blueprint for a life in line with equality.

It was all embedded in the research of a guy named Orson Squire Fowler, and fell under the umbrella of “Phrenology,” which is essentially a flawed, dangerous system of logic that tries to correlate arbitrary human physical characteristics to things like intelligence – or, in Fowler’s case, justify slavery. It was ironic, then, that the abolitionist Clubb grazed from his philosophies to combat slavery. Clubb sold the idea of a utopian world in which everything was octagonal, from farms to public buildings, that welcomed everyone (they were a little more lenient about vegetarianism than Fruitlands). There’d be no booze, and no meat. Society viewed the early pro-vegetarians as radical and “half-crazed,” but little by little, folks started gathering, and come spring, Clubb was expecting some 100 new residents.

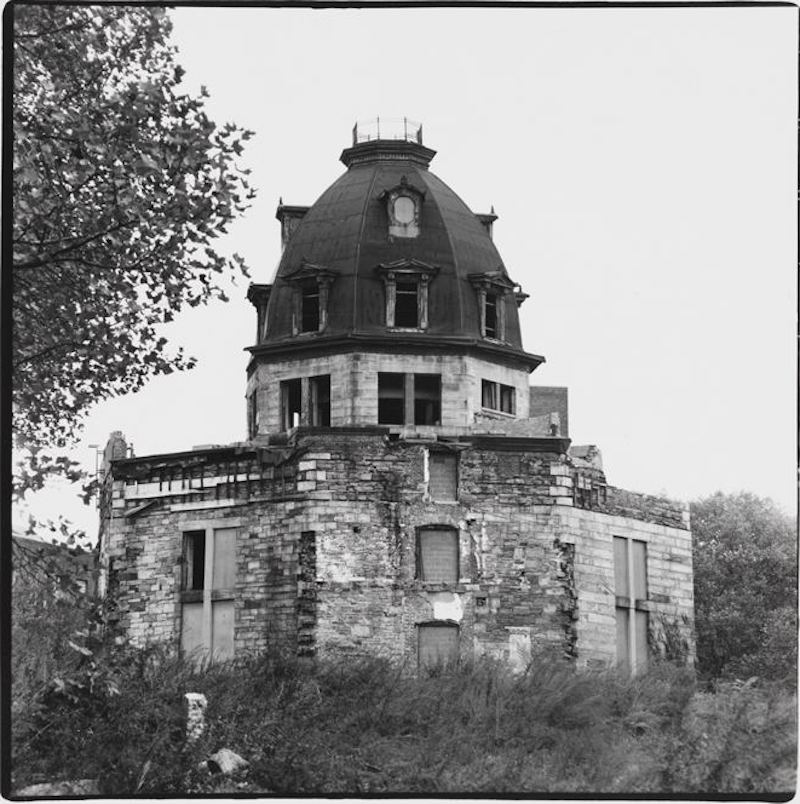

Only, instead of a gleaming octagonal city, they were met with a single octagonal dwelling and a bunch of “octagonians” living in tents. There was no booming farm life, just a single plow and a bunch of well-intentioned folks in over their heads. There were Border Ruffians to deal with, as well as disease, the cold, and basically everything else you’d expect from eternally camping. Clashes with the nearby Osage Native American tribe didn’t help, and come 1873, there were only four die-hards left. Amazingly, up until 2007 the site was something of a ghost town, and, sadly, wasted away with time and vandalism. Still, the settlement would be one of the most pivotal amongst the many octagonal structures (of which there were many) in the 19th century.

Home

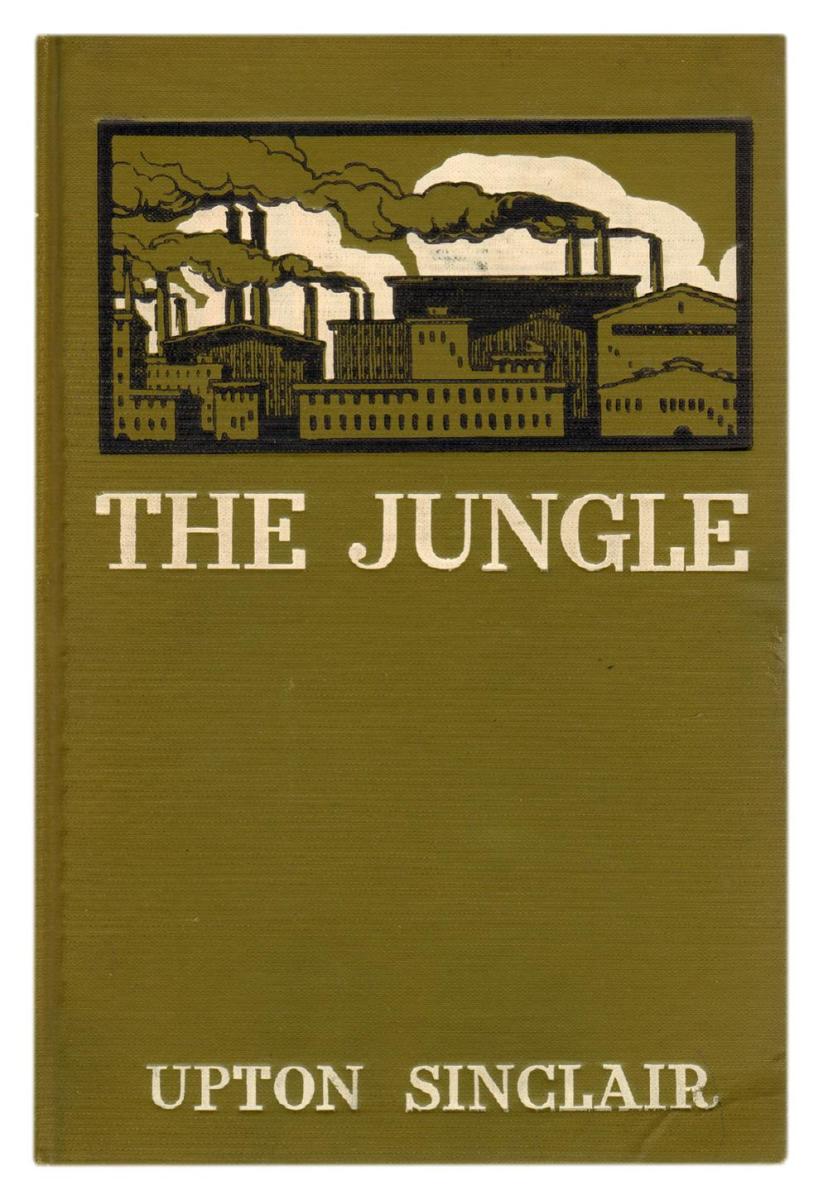

We love a good utopian colony wrapped up in a socialist manifesto, veiled with a gnarly metaphor (i.e. the violence of the meat industry), and such was the case with this short lived ‘utopia’ in New Jersey, founded by the radical The Jungle (1906) author, Upton Sinclair. A piercing critique of the meat industry and capitalism, Sinclair’s novel has been hailed as “the Uncle Tom’s Cabin of wage slavery.” And it was with all the book’s proceeds that Sinclair founded his own experimental community: “Home”.

The colony also drew heavily from another book by Charlotte Perkins Gilman, The Home, which basically rips a new one in the patriarchy re: domestic work and women. Sinclair had envisioned yet another farming community, albeit one an hour away from the metropolis of New York City, and, as such, an attractive place for prominent “authors, artists, and musicians, editors and teachers and professional men.” So he bought 400 acres of land in Englewood, New Jersey, repurposing an old school house as the hub. He called it, the “Helicon Home Colony.”

At first, “Home” was sounding pretty good. Sinclair wanted to invest in cutting edge domestic technologies, and integrate them into the communal spaces to eliminate what he saw as a classist need for domestic staff. He also planned for members to be part of a cooperative, and build homes of their own design. The only rule? Kitchens and child-rearing areas were in a shared space. There was a big old press conference where backers and potential members ironed out the details, and The New York Times actually wrote up a pretty kind report. It was hard enough to raise kids in the city, it said, so hats off the Sinclair for at least trying to do something about it.

Sounds great, no? Which it was, if you were middle-to-upper class, white, and Christian; Home restricted black and Jewish people from joining, and generally targeted a specific bourgeoise-intellectual class with its investing fees (women had to pay $10 just to vote, or about $270 today). First there was heated disagreement about how to structure the land use, then about how to structure the coop, and it was just when the plumbing broke down that the commune cracked and hired domestic staff. Five months later, the community of about 70 people disbanded. For the rest of his life, though, Sinclair would say that he thought he got pretty close to paradise – saying he had “lived the future.”

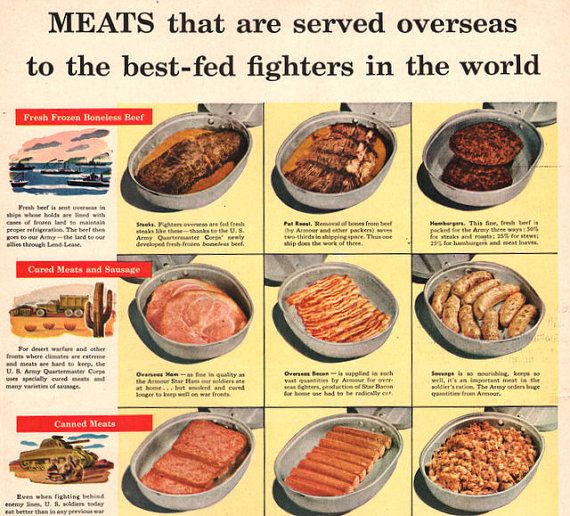

Despite a string of failed 19th century vegetarian utopias, the movement was still gaining some traction going into the 20th century, but then came war. Probably the worst thing to happen to the vegetarian movement was the devastation and loss of human life in WWI and II. Who could care for animals at a time when men, women and children were being marched into their own slaughter houses? Not to mention, Hitler himself was famously a vegetarian, which did no favours for the movement’s PR either.

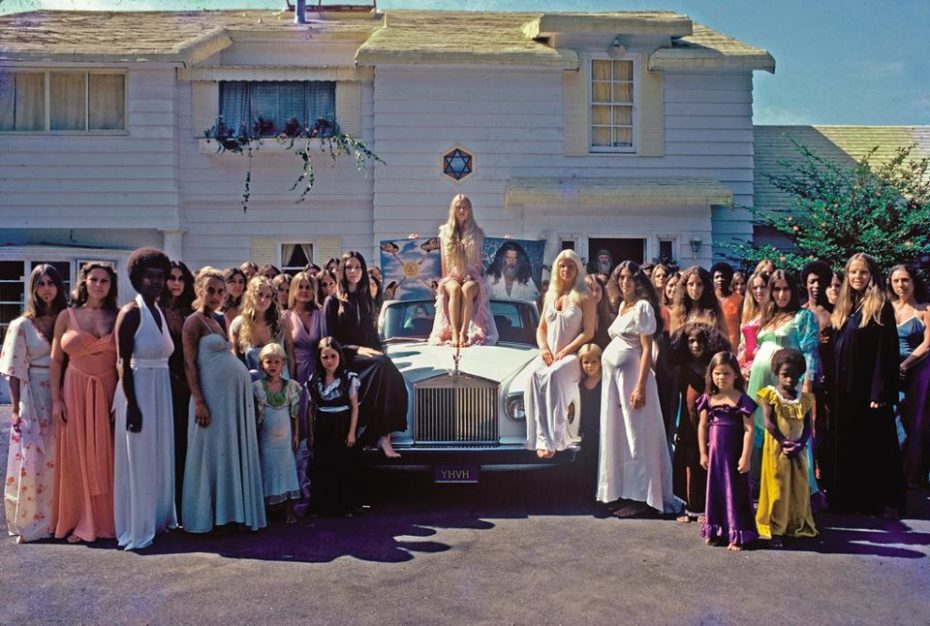

It wasn’t until the hippie communes began exploring vegetarianism again (among other things) in the 1970s that Westerners began reconsidering their consumption of meat. So on that note, cheers once more to all the hippies (from the 1870s to the 1970s) for making it okay to be weird, different and even … vegetarian!