I’ve been digging through the archives of the Met Museum again. You’d be surprised how many fascinating stories of dormant fashion brands are buried in there. They ceased to exist for a variety of reasons, but many of the individual designs kept in the collection reveal a direct path of inspiration for well-known designers today. A handful of the fashion houses have been revived, notably by Arnaud de Lummen, who has has built a successful business resurrecting dormant brands, but I was most interested by the sleeping brands that haven’t yet found their ‘Prince Charming’…

Madame Grès (1940s & 50s)

Swoon. She was called the “Sphinx of Fashion” and the “Queen of Drapery” Madame Grès, aka Alix Barton has clearly left a lasting impact on haute couture and the fashion industry in general today.

Notoriously private and dedicated to her craft, Alix originally studied painting and classical sculpture. During the war, the German army shut down her couture house after she refused to design utilitarian clothing and defiantly continued to create her signature Grecian goddess dresses – in the colours of the French flag no less. After the Liberation of Paris, Alix re-emerged from hiding to solidify her position as a leading French couturier of her generation. She made dresses for the Duchess of Windsor, Paloma Picasso, Grace Kelly, Marlene Dietrich, and Greta Garbo. She retired from her house in the late 1980s and the last garment she designed was a dress ordered by Hubert de Givenchy in 1989.

Sadly, the end of her story is less of a fairytale. Not only did Madame Grès go bankrupt as a company after her retirement, but the designer herself died in poverty after a string of ill-advised financial decisions. Fortunately, her friends were none other than Hubert Givenchy, Pierre Cardin, and Yves Saint Laurent, who put her up in a Parisian apartment where she sewed garments for them until she died at the age of 90. Her death was not announced for a year. The perfume house she created for Madame Grès still exists today in Switzerland, but the licensing had been sold to a Japanese company before her death. Her legacy continues to resonate today, credited with convincing Cristobal Balenciaga to open his couture house. “She is a woman who counts for so much in the history of fashion,” said Azzedine Alaïa.

Madeleine Vionnet (Pre-WWII)

Established in 1912, by Madeleine Vionnet, the house closed its doors in 1939 at the outbreak of World War II. Often credited with “inventing” the bias cut, although more accurately, Vionnet was the designer that popularised it, it wasn’t until John Galliano came along in the 1990s and rediscovered the technique and revived it for Dior.

In the 1920s, it was Madeleine and Coco Chanel that were first moving away from stiff, formalised fashion to sleeker, softer clothes. Vionnet was dubbed “the Queen of the bias cut” but she lacked the talent for self-promotion and retired in 1940, while Chanel came back stronger than ever after the war.

Vionnet was actually revived in the 1990s by Arnaud de Lummen and re-launched ready-to-wear in 2006 with Hussein Chalayan as creative director, but the brand has once again gone quiet under new direction. Currently owned by a Kazakh businesswoman Goga Ashkenazi, the company’s website is inactive and has no presence on social media.

Callot Soeurs (1910s & 20s)

It was with the Callot Soeurs, one of the leading fashion design houses of the 1910s and 1920s that couturier Madeleine Vionnet refined her technique as head seamstress. She once said that “Without the example of the Callot Soeurs, I would have continued to make Fords. It is because of them that I have been able to make Rolls-Royces.”

One of their biggest clients, was a socialite known as the “most picturesque women in America Rita de Acosta Lydig, who posed for Giovanni Boldini in Callot dresses. When Rita discovered her husband was having an affair with a woman who lacked a dress sense, she allegedly sent the mistress to Callot Soeurs for a make-over.

By 1920, after the death of two sisters and the retirement of a third, Marie Callot Gerber was left to run the business alone. When she died in 1927, Le Figaro said “one of the most beautiful figures of the Parisian luxury business has now disappeared.” Her son took over the house, but similarly to Vionnet, the business did not survive the war and the company finally closed in 1952. Best known for their exotic detail, at their height, American Vogue once called the four sisters the “foremost among the powers that rule the destinies of a woman’s life and increase the income of France.”

Adolfo (1960s & 70s)

An unpaid intern for Coco Chanel turned couturier for some of the most powerful women in America, Adolfo Sardiña was a Cuban-born American fashion designer who started out as a milliner in the 1950s. With financial backing from Bill Blass, he set up a studio in New York and attracted a loyal set of clients including the Duchess of Windsor, Nancy Reagan and Gloria Vanderbilt. Even after finding success, he returned to work as an unpaid apprentice for Coco Chanel and returned to America with his own version of the “Chanel jacket”, which became best-selling designs stateside for many years. At 83 years-old, Adolfo is no longer designing womenswear having retired at the age of 60, however, his brand still seems to have life in it yet, seemingly focusing on licensing menswear to department stores. We think his womenswear archives could definitely do with a revival.

Gilbert Adrian (1940s)

When Paris couldn’t export its fashions during the German occupation, Gilbert Adrian stepped in and filled the gap for American women and had a strong influence on American fashion until the late 1940s. Fun fact, Adrian designed the red-sequined ruby slippers worn by Judy Garland in The Wizard of Oz and he enjoyed a highly successful career as a costume designer for Hollywood.

After he suffered a fatal heart attack, the designer was posthumously awarded the Tony Award for Best Costume Design in a Musical. Better-known as a costume designer than high fashion designer, his archive pieces ironically feel very high fashion decades later.

Jessie Franklin Turner (1920s)

Mostly, we just love how this sweet-looking little lady from St. Louis, Missouri caught the attention of the Parisian King of 20th century fashion, Paul Poiret (another famous house that disappeared into oblivion only to be revived a century later).

Poiret said that Franklin Turner was “the only designer of genius in the United States.” She’s been remembered as possibly the only American dressmaker at that time to offer high end clothing that was not imitating Parisian fashions of the day. Her unusually eclectic and striking clothing was always completely her own work. She retired in 1943 and all that’s left of her legacy today are a few examples of her designs at the permanent collection of the Met, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the Rhode Island School of Design Museum.

Mainbocher (1920s-60s)

He was the man who came before Dior, foreshadowing Christian’s “New Look” by nearly a decade, when he came out with the nipped-in “wasp waist” that reinvented the silhouette of the thirties. “Mainbocher is really in advance of us all, because he does it in America,” said Dior himself.

Main Rousseau Bocher set up his first fashion house in Paris in 1929, where he attracted an exhaustive list of loyal famous clients including Diana Vreeland and most famously, Wallis Simpson. He named his own shade of blue after the Duchess and designed her wedding dress, which became “one of the most photographed and most copied dresses of modern times.”

The designer was forced to flee to New York during the war, but unlike many other couture houses that closed, Mainbocher thrived on the other side of the Atlantic. He designed uniforms for the women’s NAVY, the Red Cross and the Girl Scouts, and worked around rationing by designing shorter cocktail dresses, transforming evening wear.

He retired at the age of 81 and closed the doors of his house at the start of the 1970s. The dormant brand is currently owned by an investment company in Luxembourg.

The corset from Mainbocher’s Parisian era was forever immortalized in Horst P. Horst’s most famous photographs, known as the “Mainbocher Corset.”

Lucille (1910s)

Lucy, Lady Duff-Gordon, aka. Lucille, is an interesting one. She was a Titanic survivor in Lifeboat No.1. Later, she and her husband both took the stand in an inquiry, accused of bribing the lifeboat’s crew not to return to save swimmers out of fear the vessel would be swamped.

Despite her questionable character, she was the first British-based designer to achieve international acclaim, acknowledged for her innovative couture and savvy public relations skills. She wrote monthly columns for Harper’s Bazaar and Good Housekeeping to promote her collections and took advantage of opportunities for commercial endorsement, lending her name to advertising for brassieres and other luxury items.

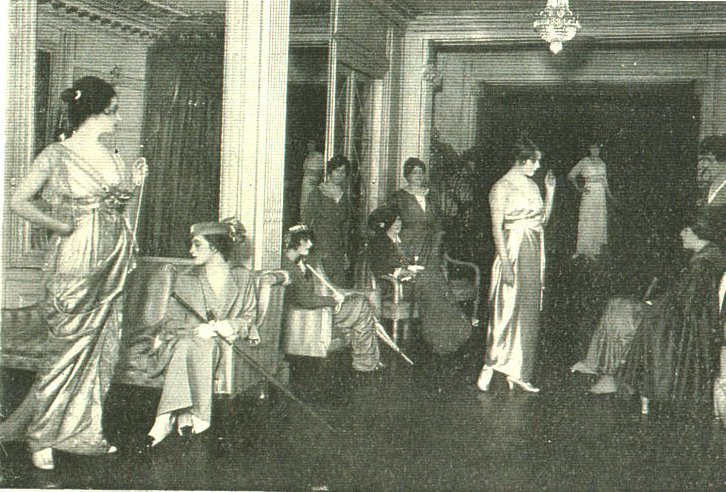

Most interestingly, Lucille is also credited with staging the first runway or “catwalk” style shows. Then called a “mannequin parade”, she trained the first professional fashion models.

Draped in her sought-after lingerie, tea gowns, and evening wear, her models were also frequently featured in Pathé and Gaumont newsreels of the 1910s and 20s.

In 1918, negative press claiming that many Lucile dresses were not designed by her plagued the company. By the 1920s, the company had closed.

Charles James (1940s-60s)

Another designer Christian Dior credited with inspiring his “New Look” and whom he called “the greatest talent of my generation”, Charles James died in 1978 nearly forgotten by all but his most loyal clients. He was notoriously difficult to work with, which many believe might have been the reason his name didn’t become one of the biggest empires in fashion.

The 2017 film The Phantom Thread, starring Daniel Day-Lewis about a renowned dressmaker at the center of fashion in 1950s, is said to have been largely inspired by Charles James.

For his earliest collection, he created a white satin quilted jacket Salvador Dalí described as “the first soft sculpture”. It’s now considered as the starting point for the modern “anorak” but James was best-known for his sculpted ball gowns made of lavish fabrics. He moved into NYC’s iconic Chelsea Hotel on the 6th floor and both lived and worked from there until his death from pneumonia. In 2014, there was renewed interest in his dormant brand and Zac Posen was set to take over as creative director, but that never materialised. Last we heard, in 2018, none other than sleeping brand revivalist, Arnaud de Lummen, was at it again, who had developed a new visual identity for the American label as its brand rights went up for sale. No word on whether anyone bought into it.