At a glance, it’s just another postcard perfect village in North Cornwall. But delve deeper into the misty valley of Boscastle, and you’ll find it harbours a special kind of magic. Literally. “There are legions of witches across Britain,” says Simon Costin when we ring him for a chat, “Or people who identify as witches or occult practitioners. Like anything else – occultism, Paganism, witchcraft, whatever stream of operative magic you want to take – there are many different belief systems within each of those things.” And they’ve all found a home here, in a storybook cottage by the river at the Boscastle “Museum of Witchcraft & Magic.” Simon, who is the museum director, a learned occultist, and probably the politest person we’ve ever interviewed, walked us through the world of witchcraft in the area. He also answered our burning questions about the occult (but were always too shy to ask!). So come along as we wander Boscastle’s enchanting streets, and untangle the truth about pointy hats, black cats, and broomsticks – and of course, the Devil himself…

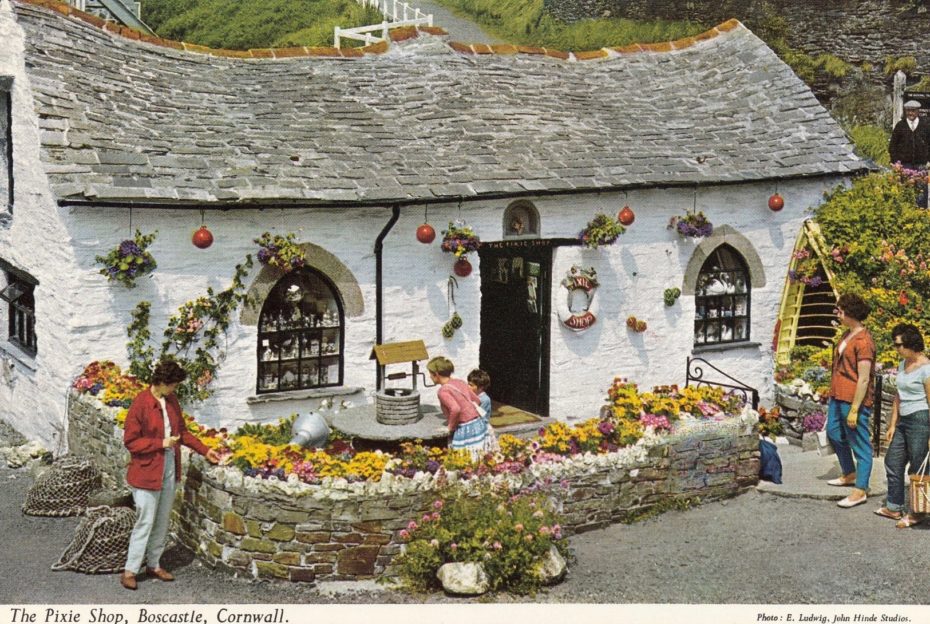

We might mention that team MessyNessyChic did physically stumble into Boscastle recently, and we can honestly say: keep your wits about you! Doze off in the car at the wrong time, and you could miss a glimpse of a cauldron perched at a home’s entryway (true story), or a souvenir shop with pentagram mirrors. Traces of its other-worldly affinities are all around, from the “Cobweb Inn” pub to the 300-yr-old Pixie Cottage, which is rumoured to have been co-inhabited by fairies. The latter was washed away in a flood over a decade ago, but lovingly rebuilt by locals.

But the heart of the town’s tender, spooky core is the Museum of Witchcraft & Magic. “There’s a strong link between Cornwall and witches,” says Simon, who explains why the museum has had a few homes since its founding in 1951, “such as a Burton-on-the-Water, and Stratford upon Avon, [but] settled in Boscastle because of the lack of resistance from the locals. In all those other places, [it] was hounded out of town by the Church.”

Boscastle opened its arms with a safe space for the museum. It’s also devilishly cosy, but don’t let that fool you; there are about 7,500 magical texts in its library, which is open for all to browse by appointment.

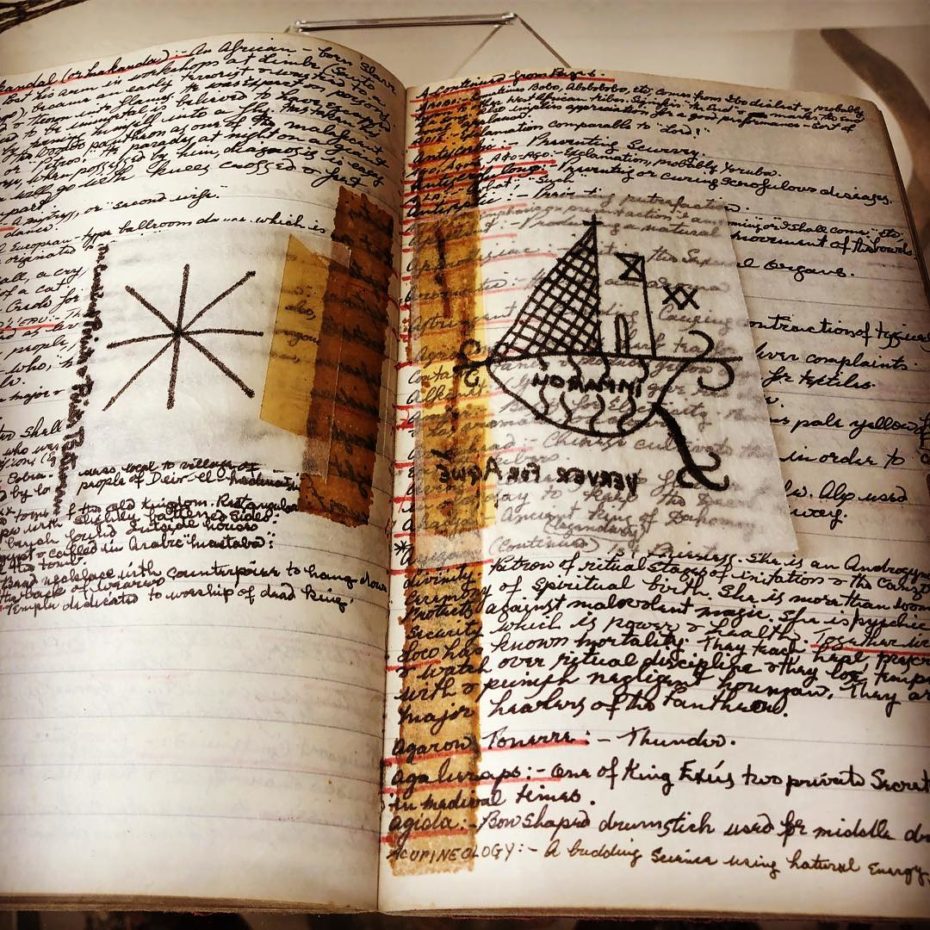

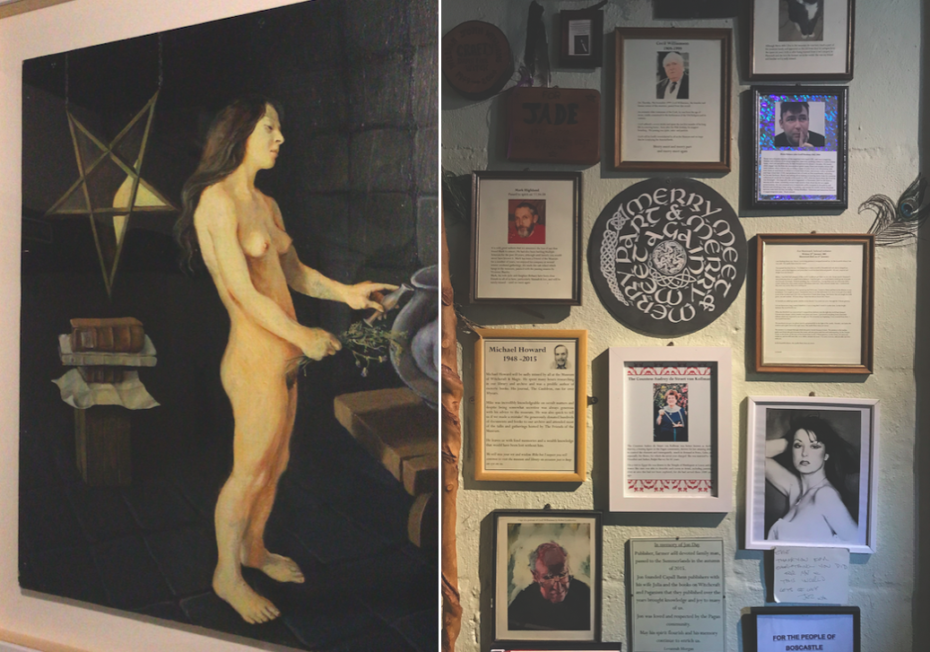

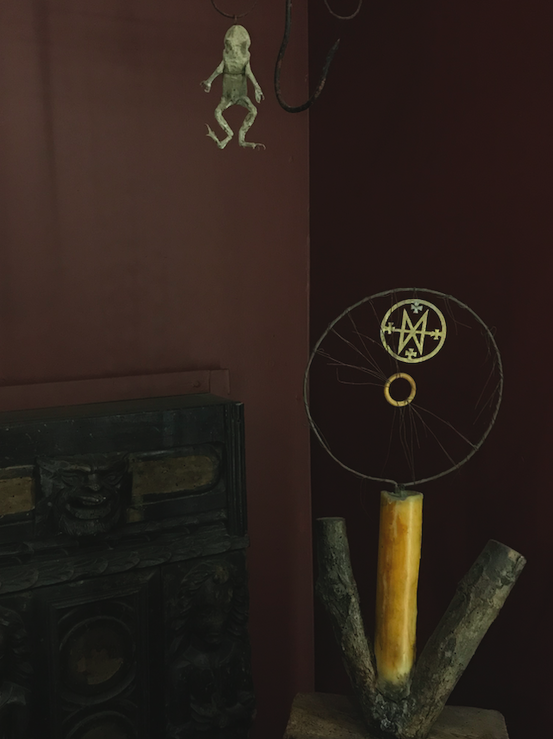

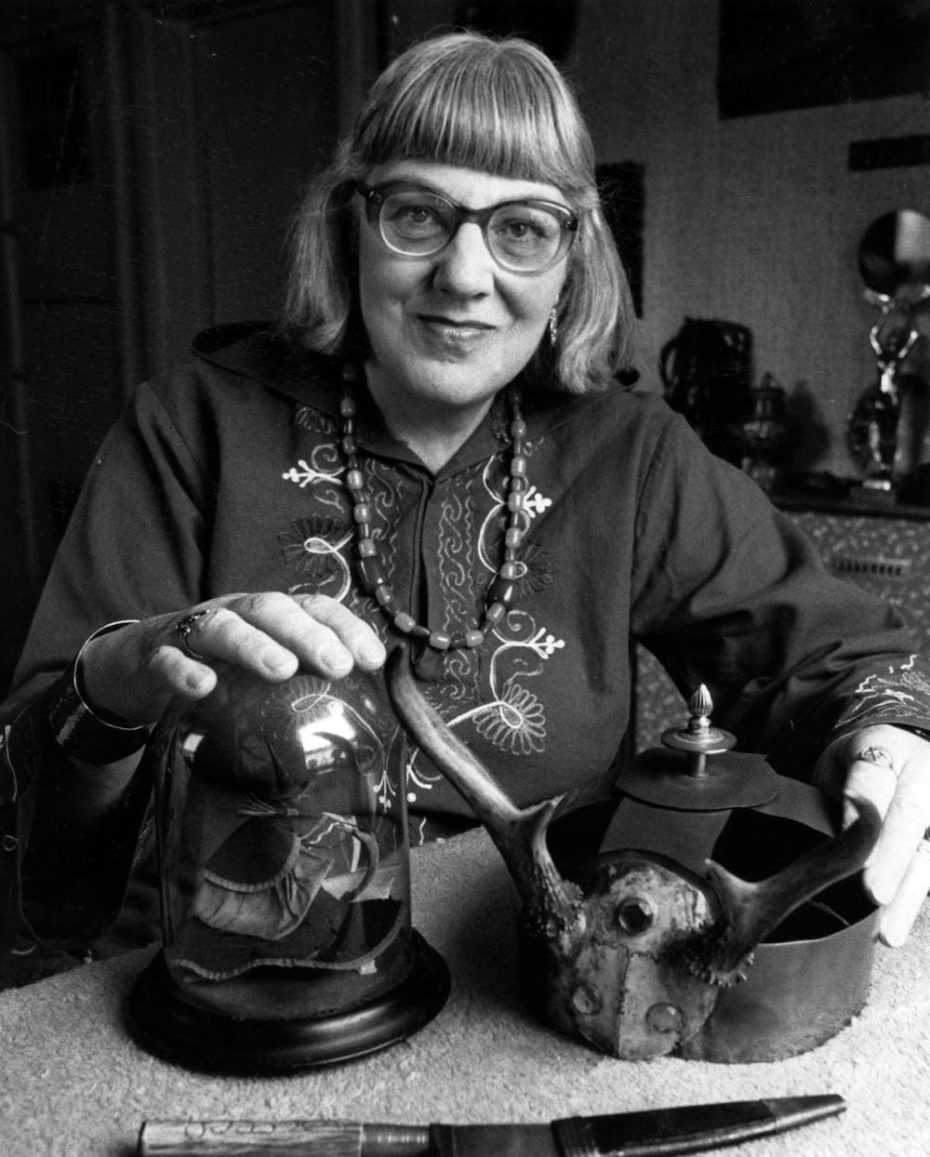

The gift shop feels like an artisanal witch’s cupboard, pre-stocked with house-made incense, curated spell books, talismans and more. There’s even a quiet space for contemplation next to a wall of meaningful, magical and occult figures. Then there’s the museum itself, which has regular rotating exhibits, and involvement in various magical events (which we’ll get into later). Talismans, photos, and potions ingredients abound, as are the witchy contents of a place called “Snowshill Manor” (ex. a ‘sorcerer’s trunk,’ a frog dangling from a hook, likely for a black magic curse, and more). There are even ritual candlesticks from a coven called “The Temple of Artemis” that were used for 66 years, up until donation to the museum…

As we walked past the glass cases of famous witches’ cloaks, altar accoutrements, and more, one tar-dipped skull caught our eye…

Please do not dislike this skull, reads the description, written by the museum’s late founder Cecil Williamson, Once it could laugh and cry like you. Those in authority decided to chop off its head and dump it in hot tar. Someone placed the head in this Bible box, which was recovered from the rubble of a London church during the war. The head responds to kindness and affection, so spare him a kind thought or smile…

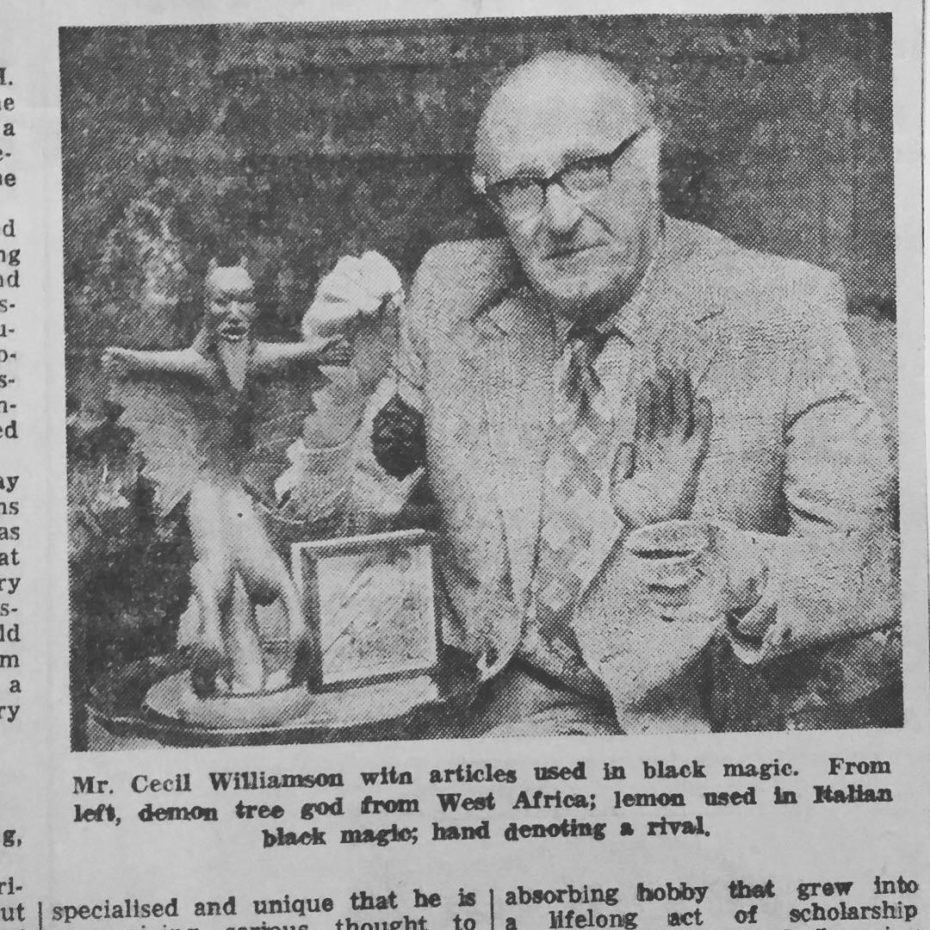

Cecil Williamson was one hell of a guy. A Devonshire lad, English Neopagan Warlock, and valuable member of MI6’s war against Nazi Germany – specifically, as an investigator of the Nazis’ occult interests. Simply put, few folks were as up to snuff on the occult as old Cece, and while following in the footsteps of a Nazi fighting warlock is a tall order, Simon is up for the task. Not to mention, he has quite pedigree of his own. As a set designer, he’s worked with the grandest couture and luxury houses in the world. He even collaborated with the late Alexander McQueen on his own line. But we digress. In the scope of the museum, Simon has become both an unexpected guardian and innovator of the collection, and its goal to educate the public on what practicing magic really means.

“One of the most popular misconceptions about witchcraft,” he says, “is that witches are in league with the Devil, or Satan, or whatever you like. In order to believe [that], you need to be Christian. The Devil is a Christian construct. And really that springs from the time of the persecution of witches in the 16th century. It was a common accusation of witches, that they were acting on the Devil’s orders as it were. The hangover from that has never really left us, to an extent.”

Only in 1998, for example, were the centuries old remains of a white witch from Cornwall, Joan White, finally put to rest at a burial. Prior, they were in the Witchcraft Museum (and apparent cause for some spooky happenings inside)…

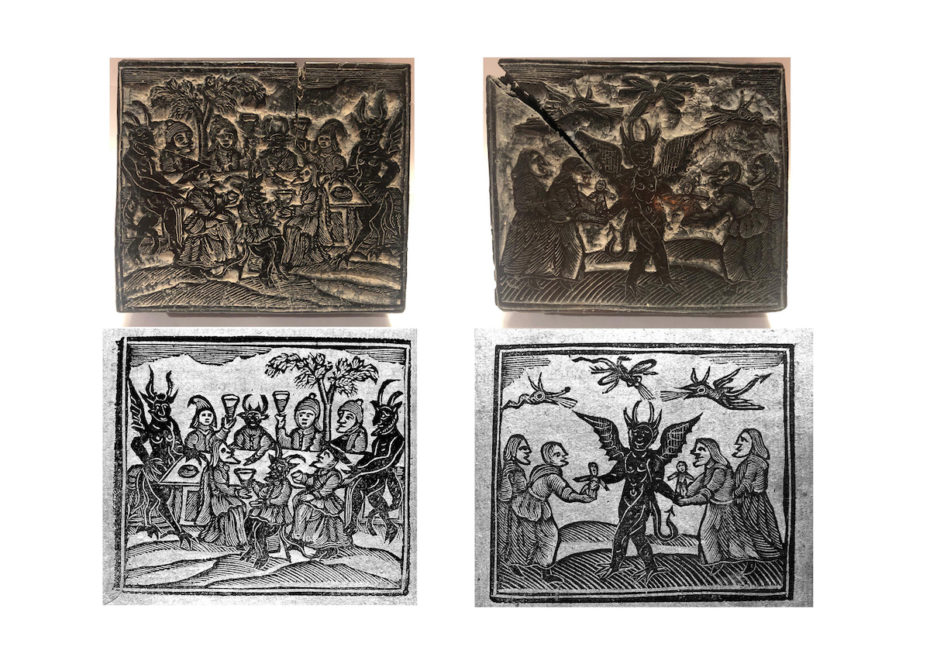

In that regard, Simon says some of the most important pieces of the museum aren’t just the pro-magic effects of famous covens, for example, but the witch-hunting relics. “One of the recent acquisitions I’m very pleased with,” he says, “are two surviving wood blocks from 1720, which were used for printing some anti-witchcraft literature. Those are pretty special – that they’ve actually survived this long. Incredibly unique, and rare.” They’re a reminder of the persecution that witches – be they actual magical practitioners, or victims of misogyny and ostracization – have endured.

Okay, but back to the Devil – what about the horned figure upstairs in the museum, and the horned figurehead in so many occult practices? “Oh, ‘Old Horny!’” laughs Simon, referring to the upstairs statue in the museum, “He is really a representation of the horned god.”

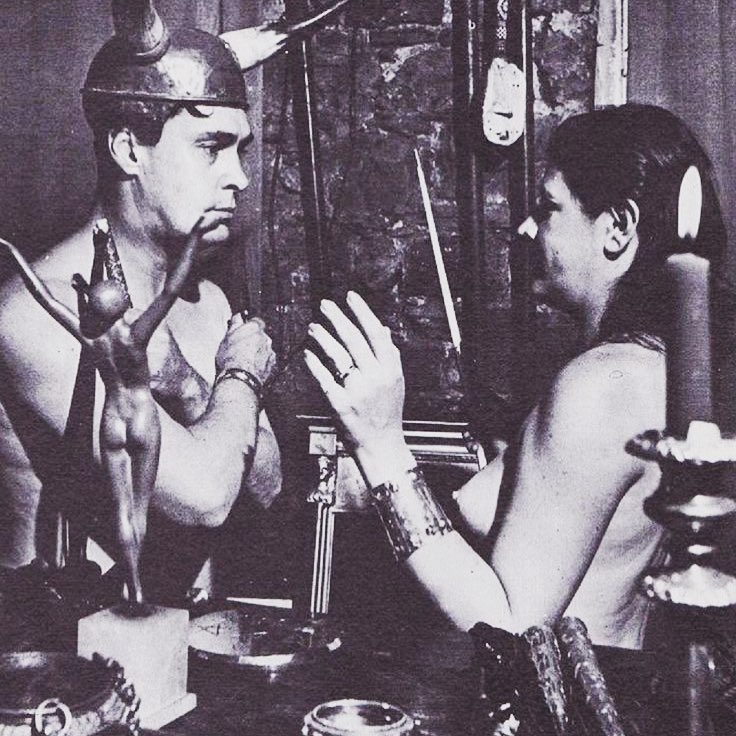

“When Wicca, which is a neo-Pagan mystery religion, was established in the 1940s and ‘50s, they worshipped both a goddess and a god. They were personified. Often, the goddess would be the maiden mother and crone, associated with the moon. The god would be a horned god, more associated with someone like, say, Cernunnos, who was a horned deity, or Herne the Hunter in Britain.”

Wikipedia

Then there’s Odon, in Norse religion. Pan, in ancient Greece – the list goes on. “There are so many of those horned, male deities, and Wiccans tend to use that personification. So that’s where those two things come from. But again, nothing whatsoever to do with Devil. It’s been coopted by early Christians.” A witch coven values nature, and kinship. Ancestral veneration is important. Life in the buff? Just fine. No body or pleasure taboos here. In fact, the more we learn about Wicca, Paganism, and the occult, the more all these witches just start to look like the OG hippies.

Simon’s suggested starter-texts for the aspiring witch? The Triumph of the Moon (2001) by professor Ronald Hutton, for a prominent analysis of the Neopagan movement, and “a very good grounding in a lot of the key figures who are involved in the current resurgence of witchcraft.” As for something written by a witch? Doreen Valiente. Hands down. “Doreen wrote incredibly [accessible] texts regarding witchcraft during the midcentury and into the 1980s,” says Simon, “She’s often referred to as the grandmother of modern witchcraft. She was truly remarkable. I would’ve loved to have met her. Sadly, she passed away before I was able to.”

Who knows, perhaps the Museum of Witchcraft and Magic has inspired the next generation’s Doreen Valiente. “What the museum aims to do,” says Simon, “is to reflect, in the most respectful way possible, the beliefs of [occultists, witches, and everyone in-between]. For many, it’s become almost like a place of pilgrimage, of knowledge.” And it wouldn’t be possible without the open-mindedness of the community on an international and local level. “There’s an air of tolerance in Boscastle,” he says, “that’s accepted the museum in a way other places hadn’t.” Which is the most powerful ingredient of all, really: kindness.

Visit the museum’s website to learn about planning your visit, and see if you can make it out to “The Dark Gathering,” which Simon calls “a magical, moving” event hosted by the museum on October 26th with “dancing, singing, and a torch lit procession in the harbor.”

As a Halloween gift from Messy Nessy, we’ll leave you with Simon’s own notes on famous witch traditions. Consider it the first addition to your magical library…

Black Cats

[They] suggest both a close relationship between human and animal and a connection to the other-world. During the period of persecution of witches in England (c.1500-1700) it was a widely-held belief that witches were undertaking the work of the devil and that he sent his spirits in animal form. These spirits or ‘familiars’ could be any animal (and in some instances a combination of more than one animal).

These animals were fed the blood of the witch in exchange for their magical powers. Curiously the association between witches and cats is an English phenomenon which is first noted in 1566 during the trial of Elizabeth Francis. Francis confessed that her grandmother had taught her witchcraft, and given her a cat called, ‘Sathan’, who had worked magic for her. While there were many accounts of witches and other animals the image of the witch and her cat has endured.

The Pointy Black Hat

The conical black hat is as part of the image of ‘the witch’ as the cat. There are many theories about why the hat was imagined as part of her clothing – including that in the Middle Ages outsiders wore pointed hats and religious non-conformists were burned wearing pointed hats. The Church was also wary of pointed hats as they were reminiscent of the devil’s horns. With such examples of other outsiders wearing a distinctive shaped hat, the idea that a witch would also wear one was an easy assumption to make.

Medieval depictions of witches often show them bareheaded with long hair, but by 1589 the renowned courtier, Robert Throckmorton, pointed out an old woman in a black hat and said

‘Did you ever see….one more like a witch than she is?’

By the 1700s the image of the witch in the black hat had become more widespread and was circulated in popular print. That image has remained and become reinforced by representations within our own contemporary culture-from The Wicked Witch of the West in ‘The Wizard of Oz’ to Halloween costumes.

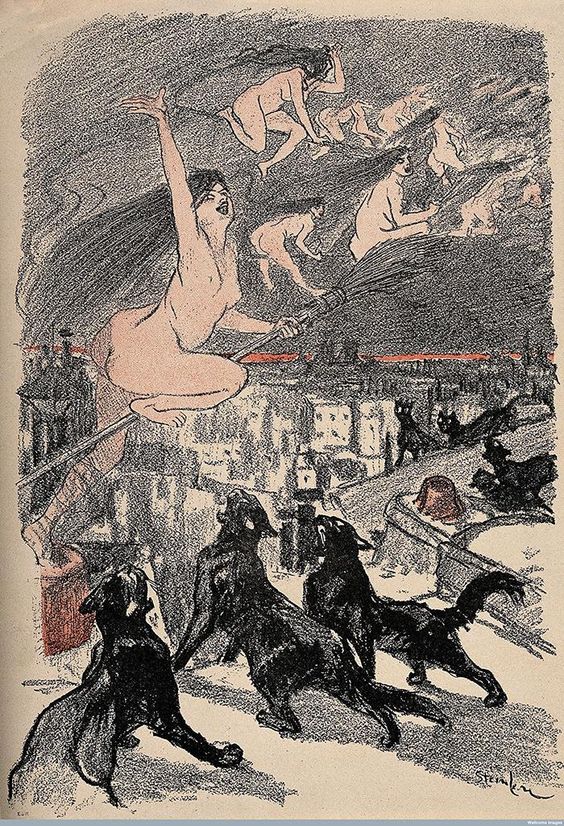

The Broom (or Besom)

Like the imagery of the witch’s black cat and her pointed hat, the origins of how the broom became associated with witchcraft is similarly unclear.

One theory is that brooms were objects directly linked with poorer women, and as the idea developed that witchcraft was itself a preoccupation of poorer women the two became combined. Other domestic objects such as ladles, cupboards and eggshells have also been portrayed as means of witches taking to the air and the ability to fly.

Traditionally made with sacred woods – an ash handle, birch twigs and bound with willow, in the Middle Ages the broom was used in a ritual to rub in hallucinatory inducing ointments and from this may have become associated with the ability to fly.

The broom is still used in modern witchcraft as a means of symbolically cleansing ritual circles and also in handfasting (similar to marriage) ceremonies.