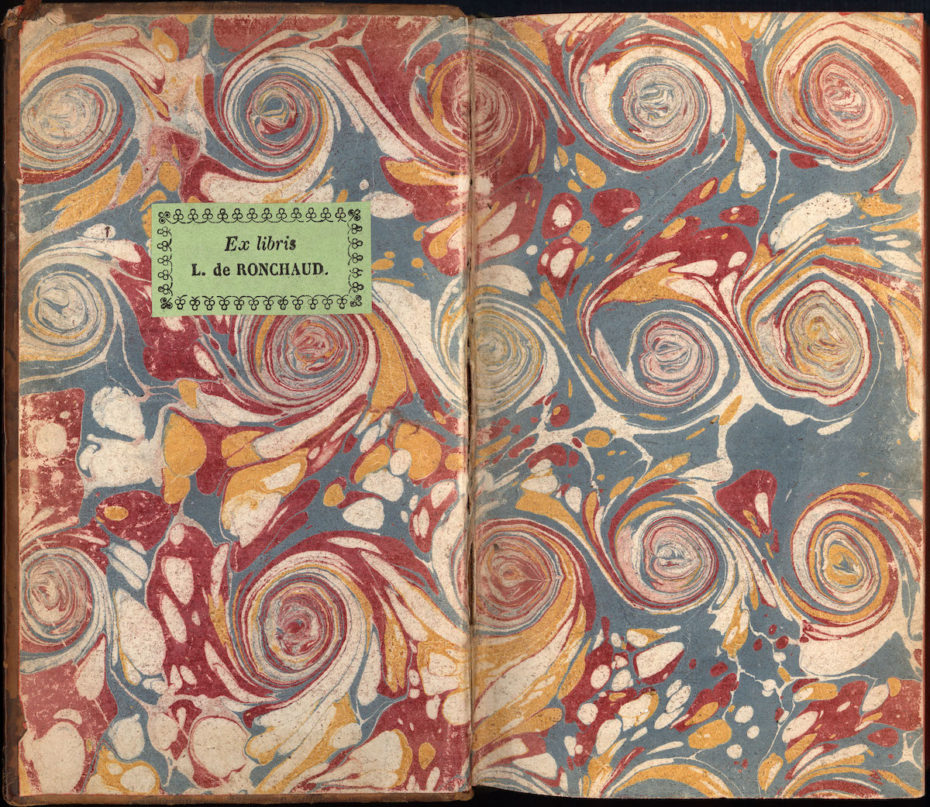

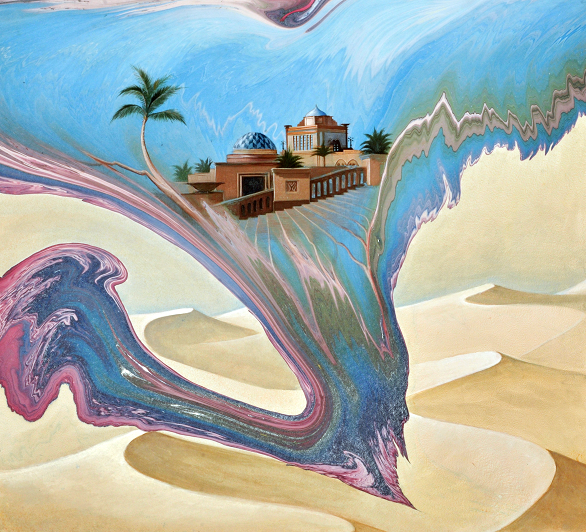

It’s the DIY to rule them all: marbling. As in, those hypnotic patterns you find inside antique books, posh stationary, and packaging where it seems as if the whole of the colour spectrum has been syphoned through a kaleidoscope and poured onto a piece of paper. So what’s the story behind the painstaking craft? That answer spans across centuries and cultures, and back almost 1,000 years to a skill-set that’s often melted into myth; a strictly guarded secret passed on from master to apprentice, a meticulous undertaking that’s been immortalised in verse, called “painting with clouds,” and at one point, even used human skin. But before we get into that, let’s watch the video that got us on this kick in the first place…

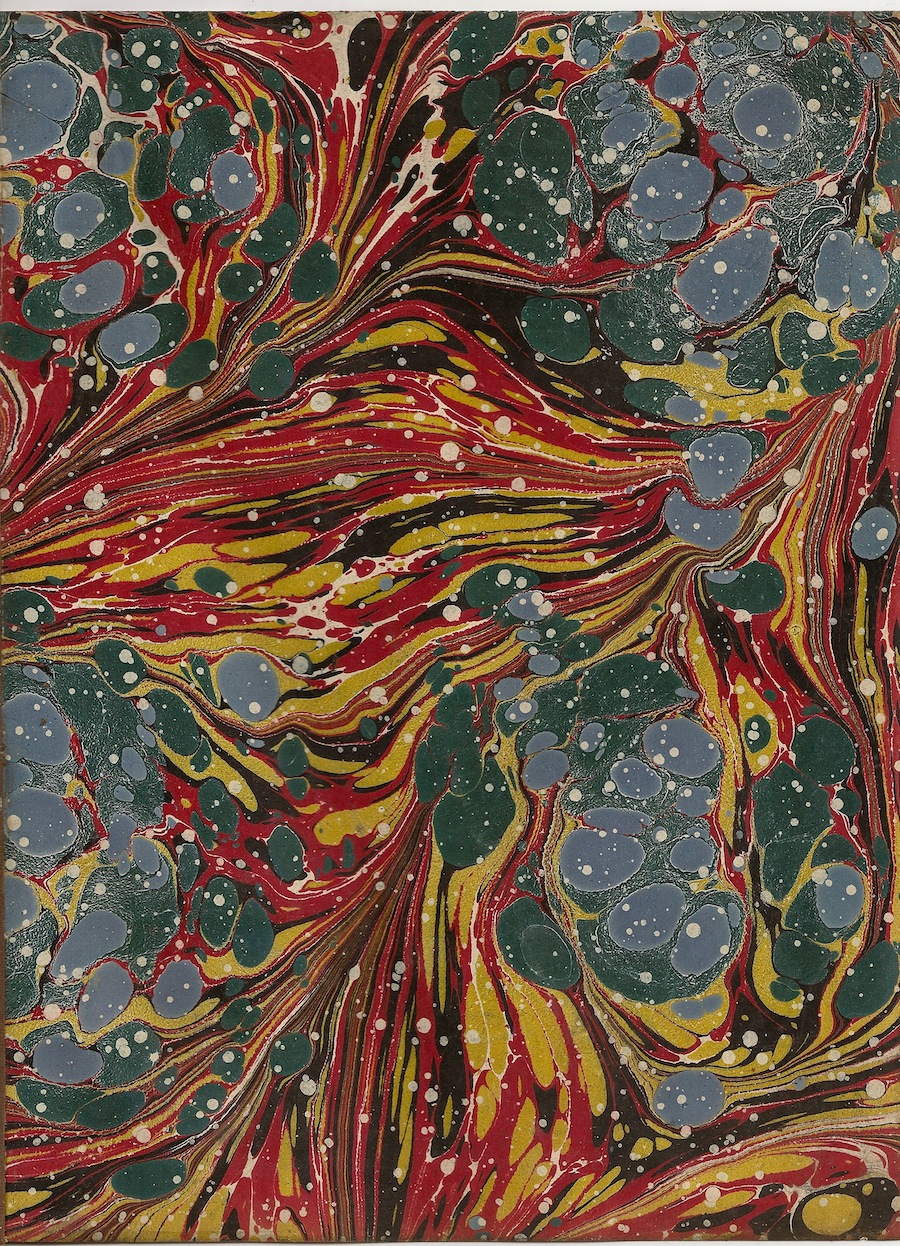

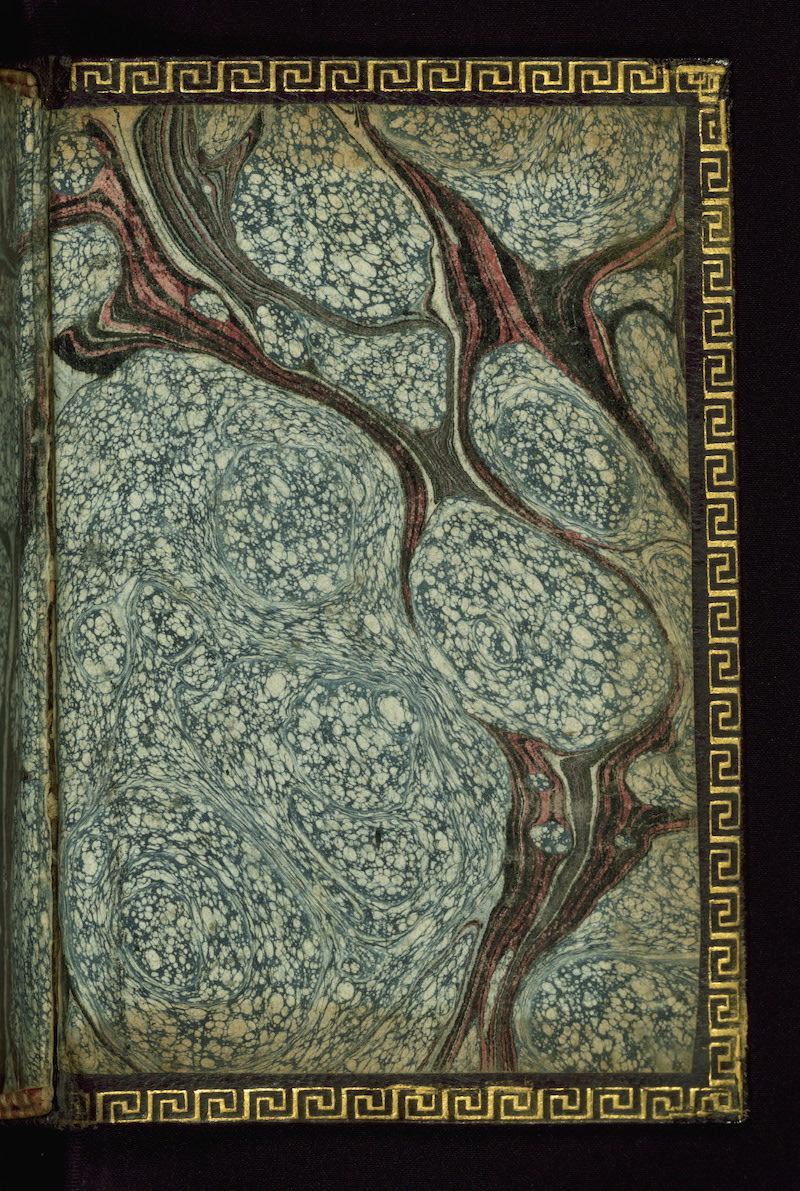

So to reiterate our 1970s British mini-doc: marbling is, above all, crazy meticulous. There are set patterns and technique to adhere to, of course, but still “every marbled paper is a separate and unique original.”

They visit the workshop of Cambridge’s environs, and it’s interesting to learn that the workshop was initially made as an extension of a book preservation department. As such, marbling was just another facet of their daily operation, but one that became so popular that they started making marbled papers and selling them to an international array of clients.

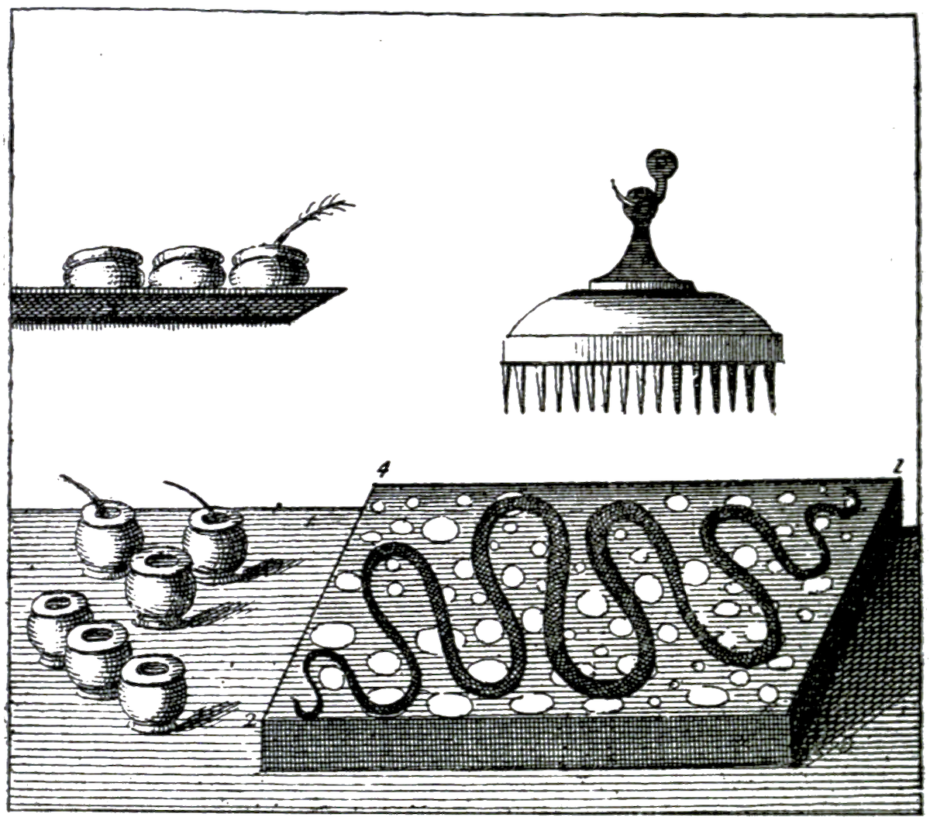

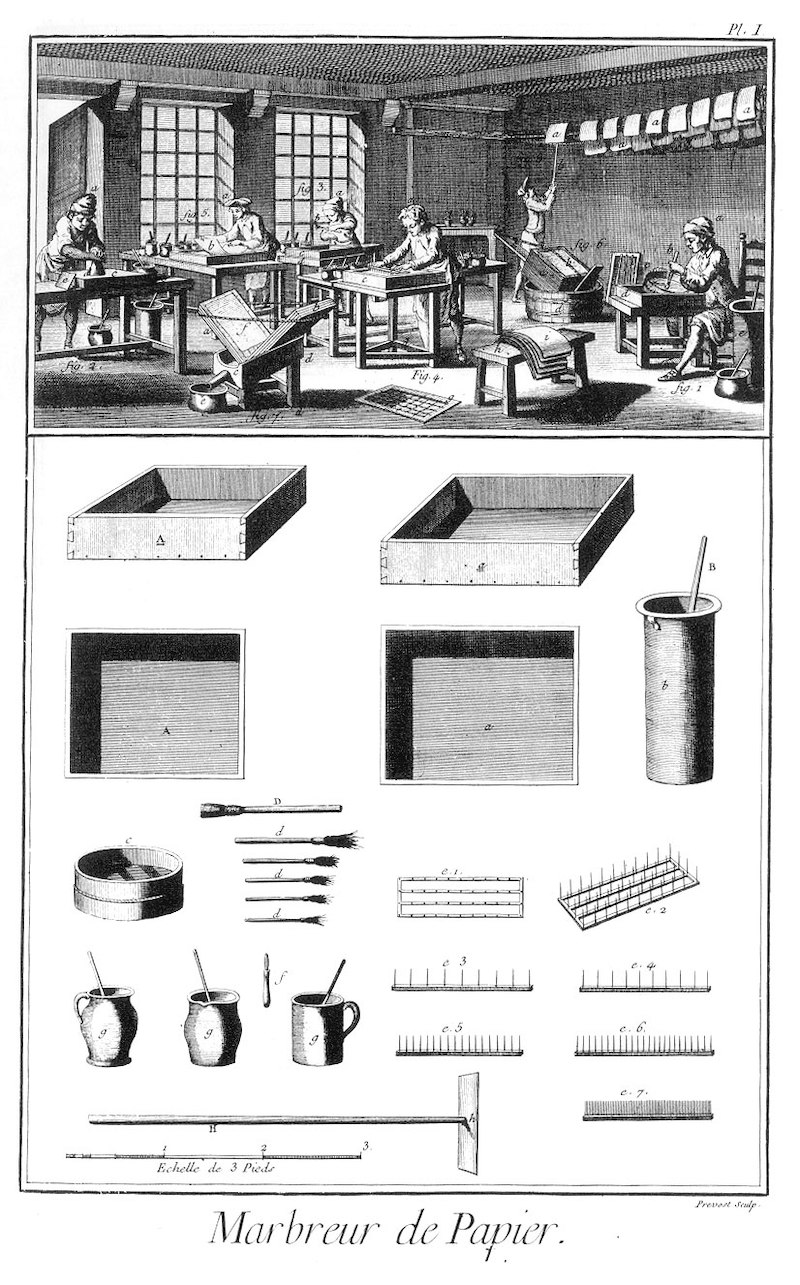

In case you snoozed through the technical process: it’s all centred around giving the paper a little bath in a kerotine and seaweed – yes, seaweed – mixture. Apparently it impedes the colours from blending, à la oil and vinegar. Other chemicals and colours are added in with the help of devices that look like doll-sized farming apparati (i.e. a three foot, square rake) that gently disperse, and comb the colours and patterns across the “bath”. And just as with your own hairbrushes, these combs, water rakes, or whatever you want to call them, vary in respect to your desired effect; some prongs are thick, others are minuscule, and so on.

Laying the paper down flat on the surface requires surgical precision. Then, you lift it back up, give it a light rinse and watch the rainbow of designs emerges when the seaweed’s residue is hosed off. The result is a stunning; sometimes, you get amorphous blobs that look like organic cells, other times, a psychedelic pattern (which explains its resurgence in popularity in the 1960s-70s).

The first marblers, however, lived far from jolly England. Their stories take us back to the reaches of the far East in the 10th century, where texts from present-day China’s Sichaun region discuss a decorative paper called Liu Sha Jian – literally, “drifting sand” or “flowering sand paper.” It was made by dragging paper through fermented paste. There were all kinds of wild ingredients used in the marbling process, from honey locust pods to ginger. In fact, in one of the weirder art mediums (although not weirdest – that honour goes to this guy) we’ve ever heard of, marblers would scatter the dandruff from their hairbrushes over the water to help disperse the colour.

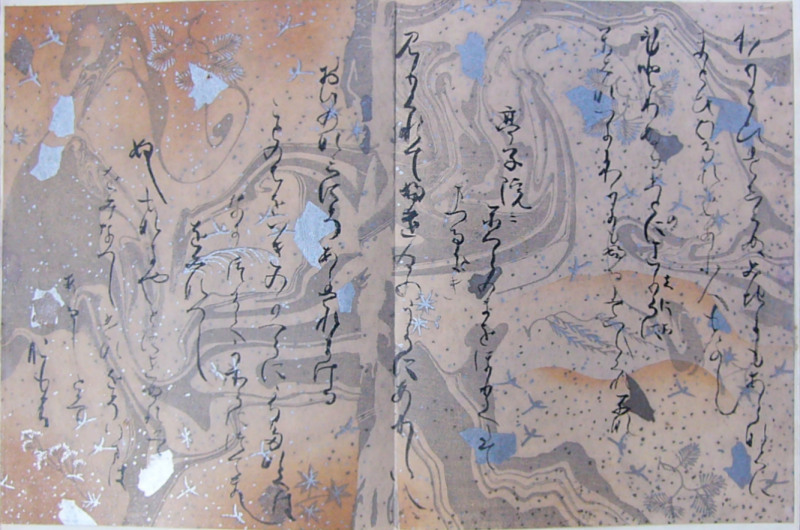

Meanwhile, Japan had suminagashi, which means “floating ink”, and was a form of marbling that waxed into the mystical (think ink, instead of tea leaf, divination). It’s also believed that the entrancing process of suminagashi became a form of live entertainment in Kyoto. According to legend, a man named Jizemon Hiroba was struck with divine inspiration when he came up with the art form, and wandered the country to find only the purest waters for his papers. The town Echizen, where he settled, remains committed to the craft, 55 generations later.

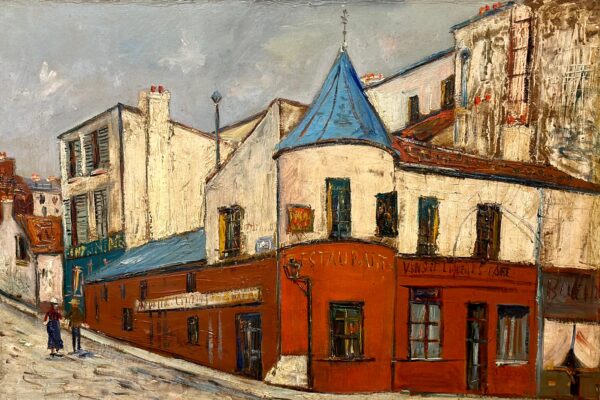

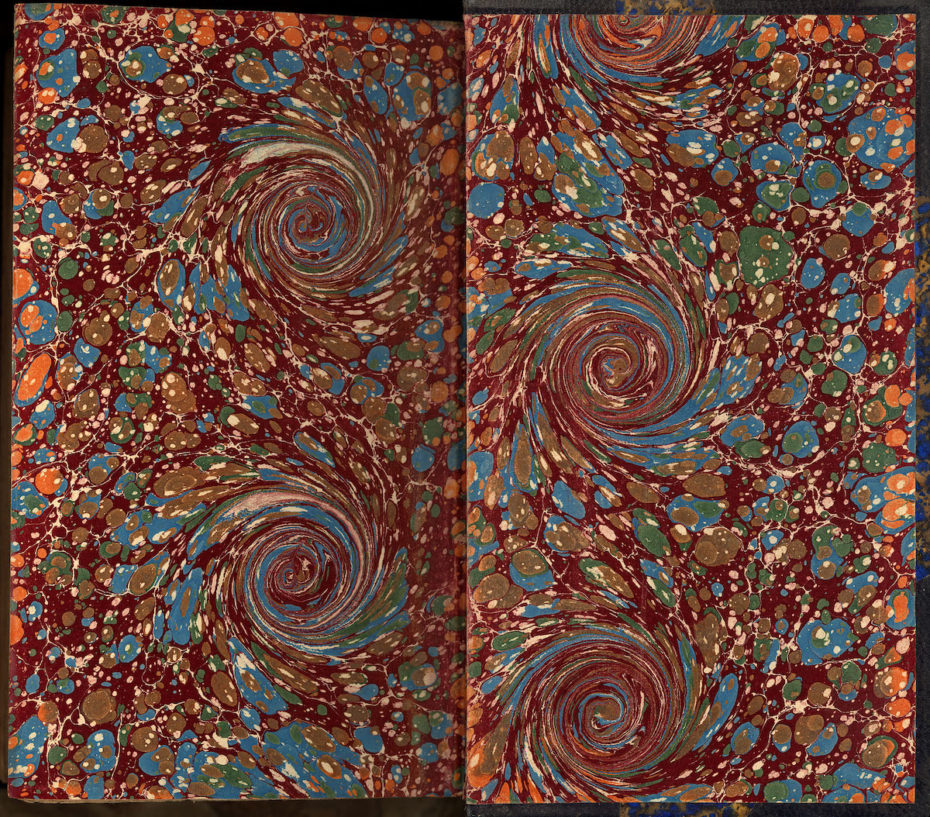

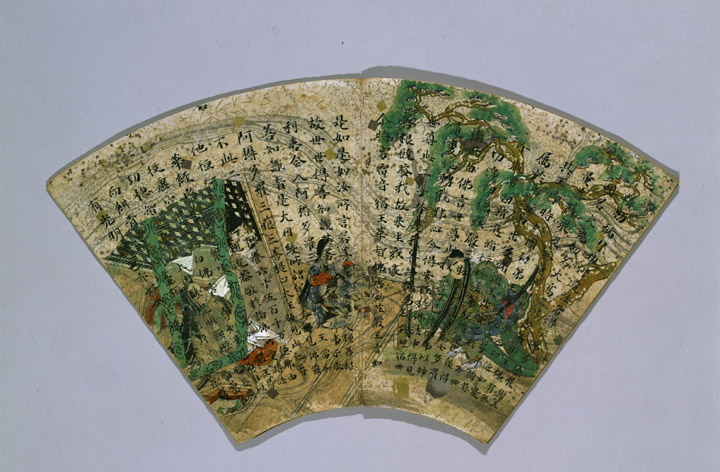

Gradually, the art form made it into Europe by way of India, the Middle East and Turkey during the Middle Ages and Renaissance – and again, often with an allusion to divine inspiration. Persian scholars called it “cloud” or “cloud and wind” paper. The Turks became some of the best in the game, contributing beautiful floral and animal patterns to the global catalogue of marbling patterns (or as they put it, Ebru). They’ve gotten so good at it, in fact, that the UN placed Ebru on its world cultural heritage list:

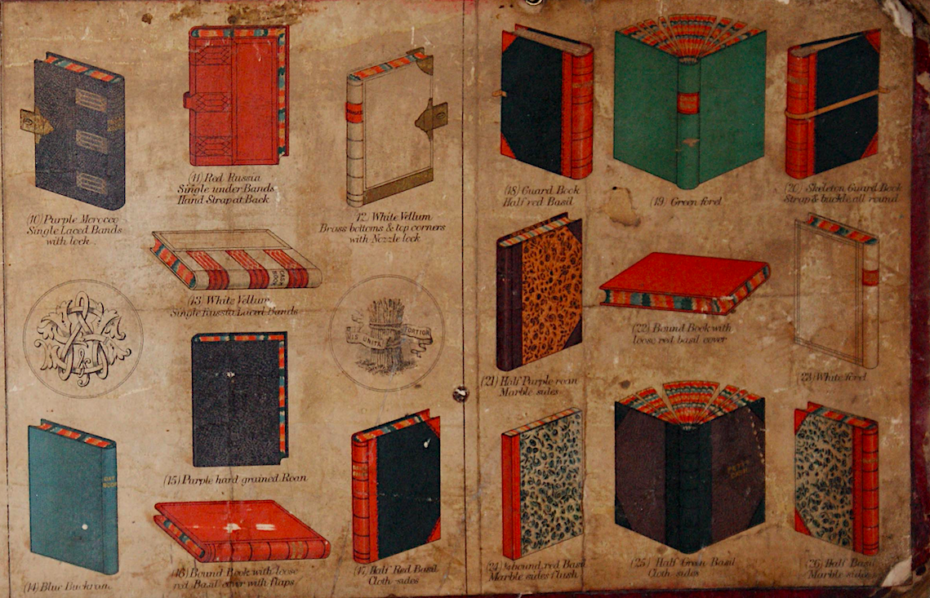

At the dawn of the Gilded Age, you had people like Charles Woolnough publishing The Art of Marbling (1853), and solidifying the craft for the generation to come as the pinnacle class for one’s library. As demand grew marbling guilds became established, each with their own patterns and secret formulas.

Which brings us to today, where the art of marbling is seemingly without limits in accessibility and imagination. Consider the Turkish artist Garip Ay, who gained famed with his Ebru interpretation of Van Gogh’s Starry Night, and who continues to dazzle with works inspired by his homeland:

Did we mention Ay also teaches workshops? Of course, if you’re keener on collecting, marbled books can go anywhere from twenty bucks to hundreds of dollars on eBay.

Not a bad gateway to art collecting if you ask us.