Wait for no muse. Make a habit of working all the time. Let your wooden sculptures grow up, and your bronze sculptures grow out. Such was the world according to Chaim Gross, the patron saint of bohemian Greenwich Village. As an Arts educator, he was bar none in passion and gave playfully acerbic advice (this is New York, after all). As a sculptor, he was on calibre with contemporaries like Modigliani and Brâncuși. Luckily, Chaim’s Village townhouse is one of the most lived-in studio museums we’ve ever seen, with an estimated 10,000 collectibles filling its walls. Works from pals like Chagall and Rothko hang casually by an AC unit. Paint brushes remain frayed, and books stacked sky high. It’s not just a museum. It’s a life-sized treasure chest.

The studio checks all criteria for a perfect rainy day museum. Cozy? Yep. Off-the-radar? Check. It reminded us of Brâncuși’s dreamy atelier-turned-musée on Paris’ Right Bank (take our word for it) or that of sculptor Antoine Bourdelle on the Left Bank (see?). This baby is the East Coast’s answer to that scene. Only, did we mention it’s even cosier?

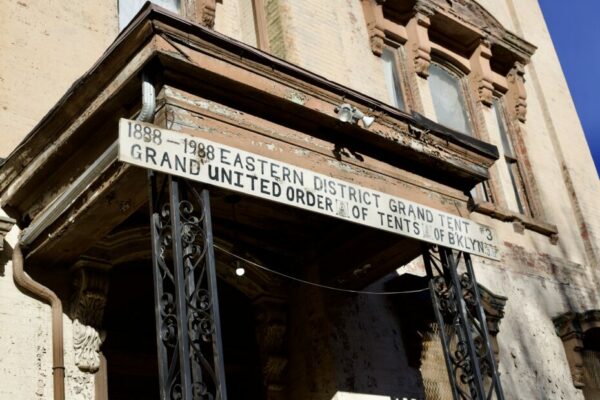

The address, 526 LaGuardia Place, looks like any other Village townhouse from the outside. You’ll enter through a narrow hall on the ground floor lined with family and media photos, which opens up to the airy atelier…

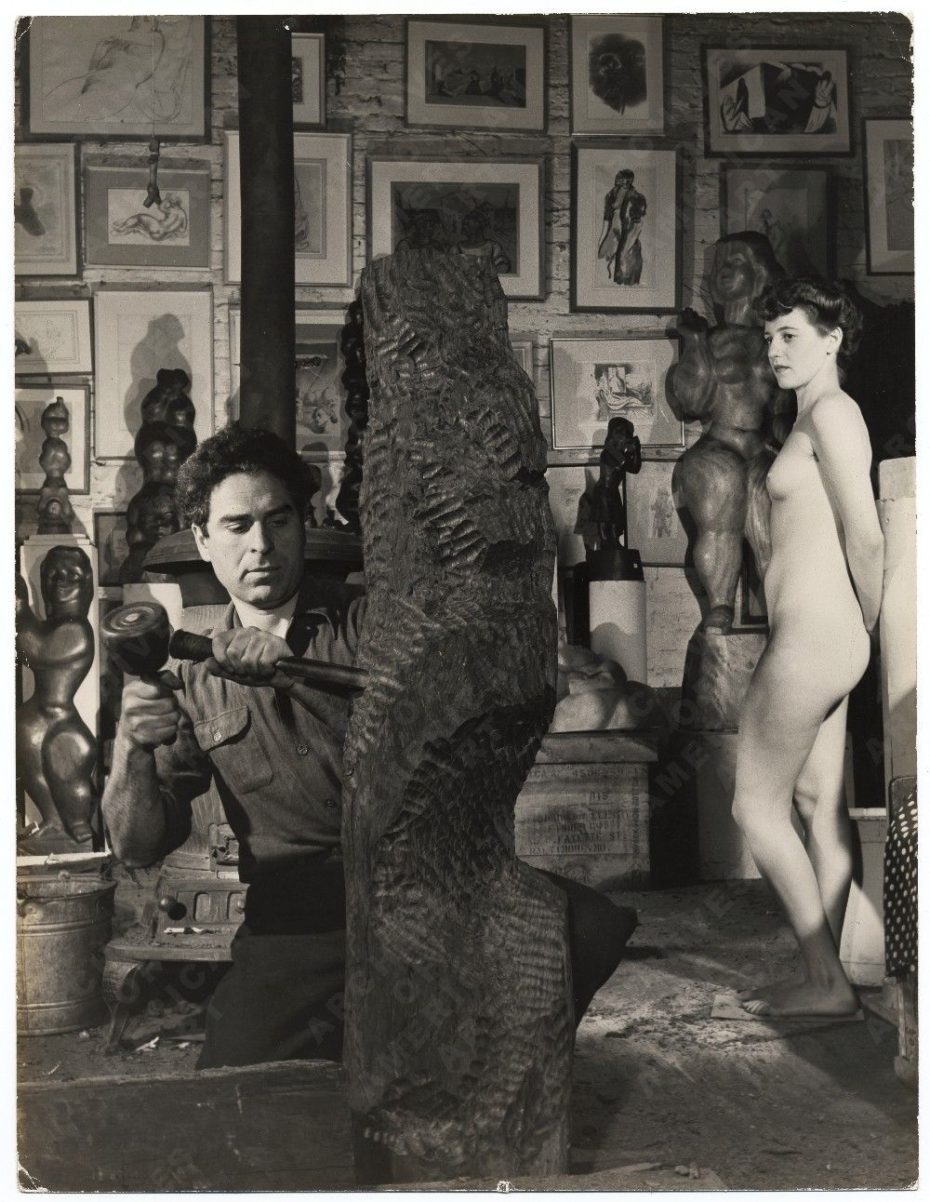

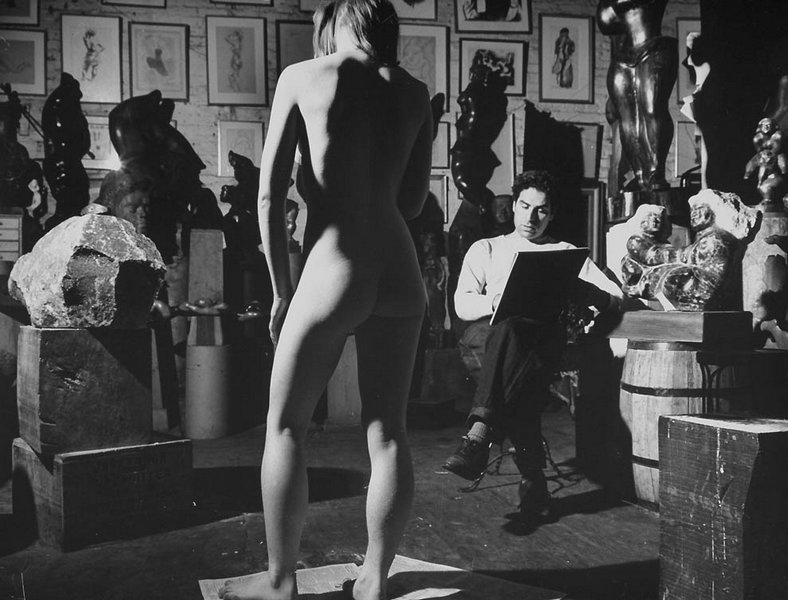

Towering wooden sculptures line your passage, like totem poles in homage to New York past. Chaim sculpted on instinct, through an emotive “direct carving” approach. There weren’t always maquettes. Just carving, motion, and a constant chipping away in his studio, which was always in the Village but moved here in the early 1960s. “Art gives me great happiness,” he once said, “when I’m not working I’m miserable.”

This is the workspace where Chaim got his hands dirty, and you can tell. There are dozens of antique drill bits and carving knives, in repose, beside his sketches and toolboxes. The brushes stand poised – as if he could return at any moment.

You don’t need to know who Chaim is to fall in love with the little universe in his townhouse. It’ll happily open itself up to you. Wander up and down three floors of the home, which are connected by a central (art lined, of course) stairway. Keep your eyes on the lookout for works collected by Willem De Kooning, Milton Avery, and Marc Chagall. (Hint: there’s a Rothko by an AC unit. That’s all we’ll give away.)

The art takes centre stage, but it’s the mementos of the artists’ everyday lives that makes the atelier come to life; a stack of cassettes in one corner, a pile of books in the other. Enough pieces of indigenous art to make Frasier Crane’s heart flutter.

Chaim was born in Wolowa, a village cradled by the Carpathian Mountains, in 1904. Back then it was considered Austrian-Hungarian; at present it’s in the Ukraine. But the most important thing to know about Chaim is that he was a hands-on guy, in matters of his own work and his call to teach in the Arts. He was a professor at six institutions across New York, including the New School.

He was also the tenth, and final child in a Hasidic family. They had to flee from Russian forces during WWI, and when they returned to Austria in 1915 it was as war refugees. When that dust appeared to be settling, Chaim began studying art in Budapest. Just a year into his studies, a new regime swept through Hungary that pushed out all its Jews. Thus, Chaim went to Vienna for an Arts education, and finally, to New York, where he continued at the Beaux-Arts Institute of Design. Lesson du jour: don’t take that homework for granted.

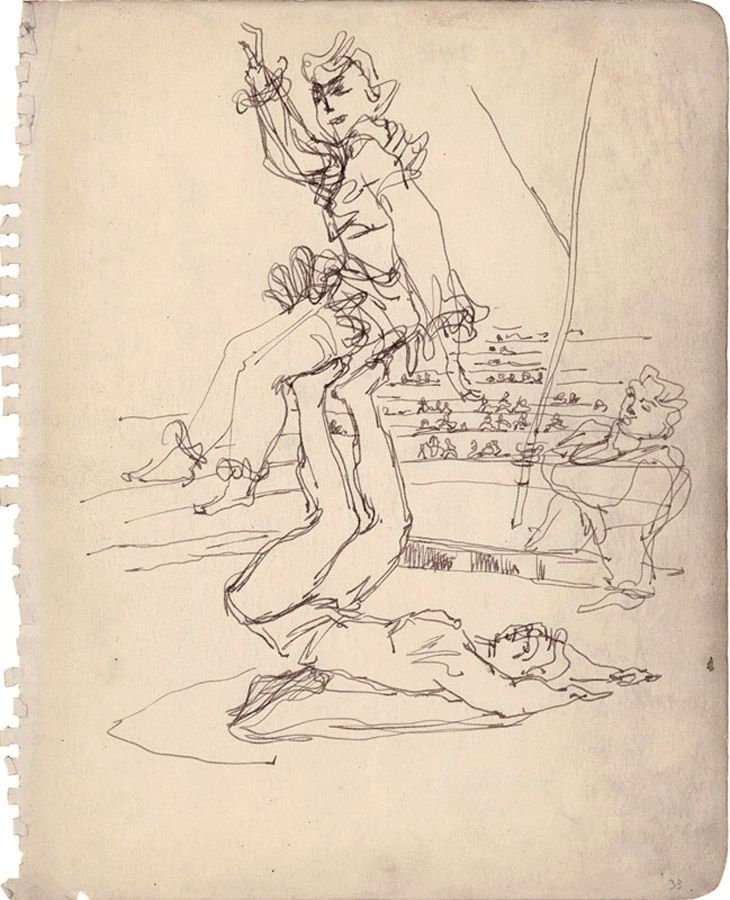

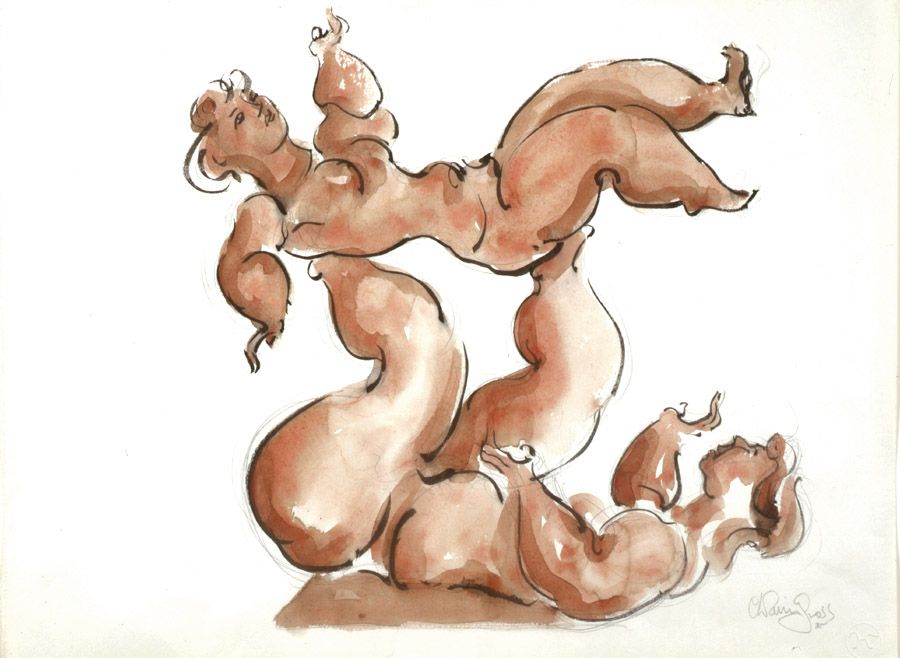

It was a professor who told him to try sculpting. His drawings were bursting with energy, begging for even more dimension…

Ink on Paper, 10 x 7 3/4 inches. The Renee and Chaim Gross Foundation.

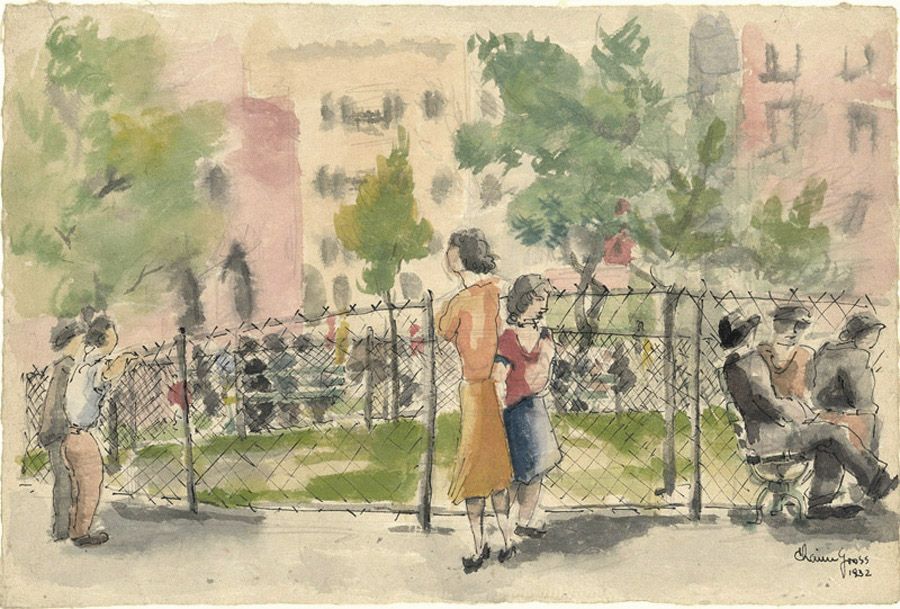

Pencil, Ink, and Watercolor on Paper, 13 1/4 x 17 3/4 inches / The Renee and Chaim Gross Foundation.

Ink and Watercolor on Paper, 9 x 13 1/2 inches. Renee and Chaim Gross Foundation

The resultant wood, metal, and stone sculptures were homages to the sacred feminine, to mother and child, and to (total 180° here) the circus. Dancers, performers and acrobats all faired well under his chisel. By the 1930s, he joined the US government’s PWAP (Public Works of Art Project) under which he taught art, and made works for public schools and universities.

Now as a hands-on guy, Chaim felt it was important for everyone – not just art students – to have a tactile relationship with art. To this day, there is an entire floor of the townhouse called “Teaching Through Touch” that’s filled with sculptures you can touch to your heart’s content…

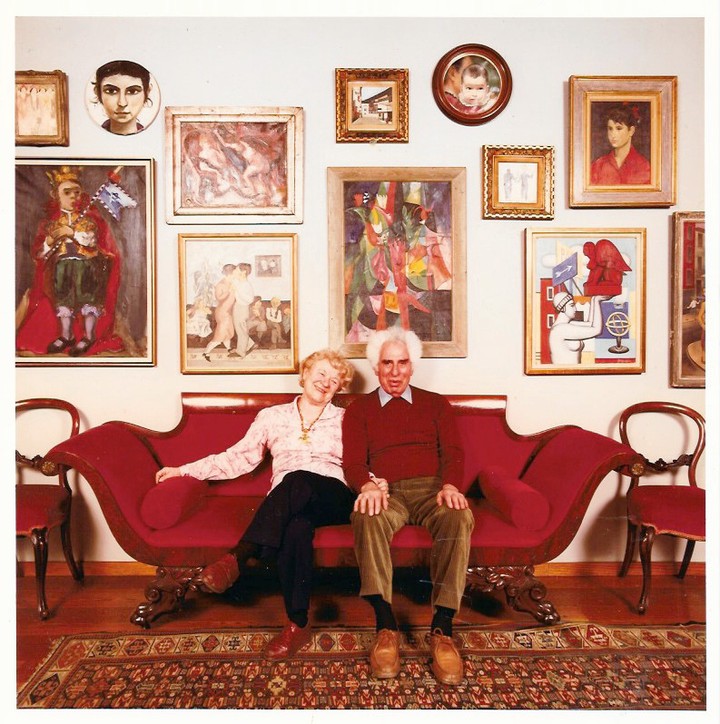

And of course, at the side of every great artist is an even greater support system. Enter Renee Nechin, the love of his life…

Renee was born in the heat of a Lithuanian summer. She immigrated with her family to New York City after WWI, and thrived amongst the freewheeling city’s bohemian scene. She was smart as a whip, a fervent anti-Fascist activist, and lover of literature. They met in the 1930s, married, and had two children, Yehudah (an engineer) and Mimi (an artist). Without Renee, we may not have “The Renee and Chaim Gross Foundation.”

Oh yeah, that charming couch? Still there.

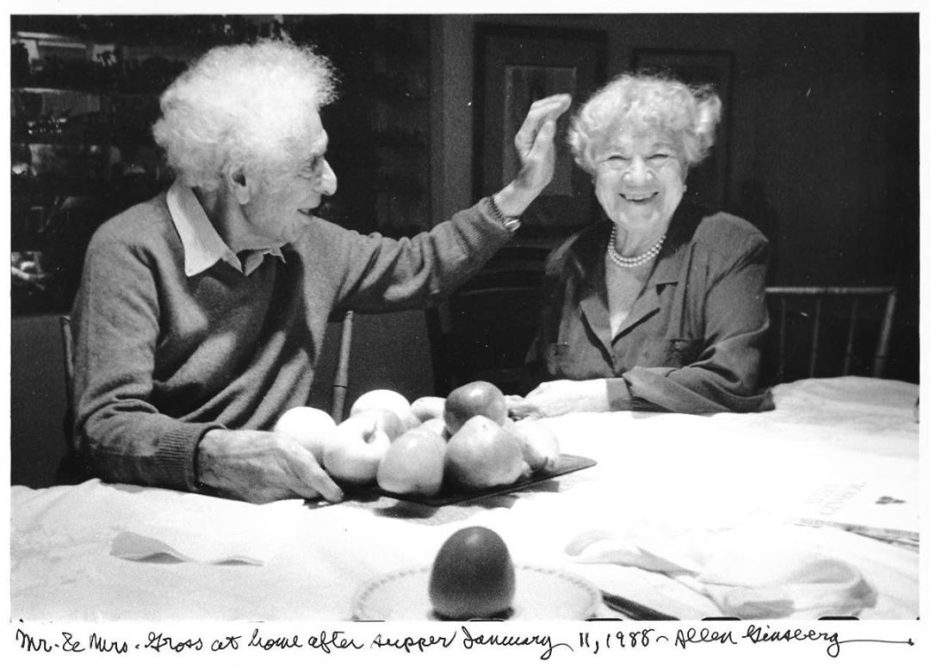

After over half-a-century of contributing to the Arts, we can’t believe Chaim is only just hitting our radar. But there is something admirable about his life’s work. He wasn’t seeking fame or fortune, though he was given due credit: he was awarded a silver medal at the 1937 Exposition universelle in Paris, and exhibited at the Smithsonian; he has public works across United States, and was paid tribute by beatnik legend Allen Ginsberg at the American Academy of Arts and Letters. Who clearly loved both Renee and Chaim. Just look at this tender snapshot he captured of them:

But for the most part, Chaim remains our little Greenwich Village secret. A man whose labours of love and joy can be seen from Bleeker Street to Walnut Hill. L’Chaim!