Hiding in plain sight, you’re looking into the eye of the last remaining example of the magnificent private mansions that once lined the Champs Élysées in Paris. Hotel de la Païva was built by a famous 19th century courtesan who came from humble beginnings in the ghetto of Moscow. Esther Lachmann, aka La Païva, became one of the most infamous women in mid-19th-century France, at a time when there was a bewildering array of categories of prostitutes that ranged from street-walkers and sex workers in brothels to courtesans and kept women. La Païva, was one of the very lucky ones indeed…

The story of her rise to become the “the queen of kept women” is still as juicy and shocking as it was then, well over a century later. By the age of 17, she was married with a son, but left her first husband shortly after giving and travelled to Berlin, Vienna, Istanbul, London and Paris. She became the mistress of a well-known French pianist, before she drove him to financial ruin and was cast out of his home. In London, during the French Revolution, she turned her attention to the British aristocracy and wealthy bankers. While making love to them, Esther allegedly demanded they burn thousand franc banknotes. She met her second husband, Albino Francisco de Araújo de Paiva, at a German spa, but no less than a day after the wedding, she gave him a letter…

“You have obtained the object of your desire and have succeeded in making me your wife … I, on the other hand, have acquired your name, and we can cry quits. I have acted my part honestly and without disguise, and the position I aspired to I have gained; but as for you, Mons. de Paiva, you are saddled with a wife of foulest repute, whom you can introduce to no society, for no one will receive her. Let us part; go back to your country; I have your name, and will stay where I am”

Esther Lachmann

Amazingly, he did as he was told and returned to his country, leaving her with his apartment and £40,000. Païva later committed suicide.

Soon after, she met a young Prussian industrialist and mining magnate, Count Guido Henckel von Donnersmarck, and followed him around Europe, pretending to bump into him at social events. She became his mistress for nearly 20 years before they finally married and began constructing the legendary Hotel de la Païva.

As the story goes, when Esther was a young courtesan in the making, an angry customer had thrown her out of his carriage on the pavement of the Champs-Élysées. It was then that she vowed she would one day build the most beautiful house on the famous avenue in revenge of all the men who had mistreated her. Her new husband was one of Europe’s richest men and paid for the mansion that is thought to have cost the modern-day equivalent of nearly a billion dollars.

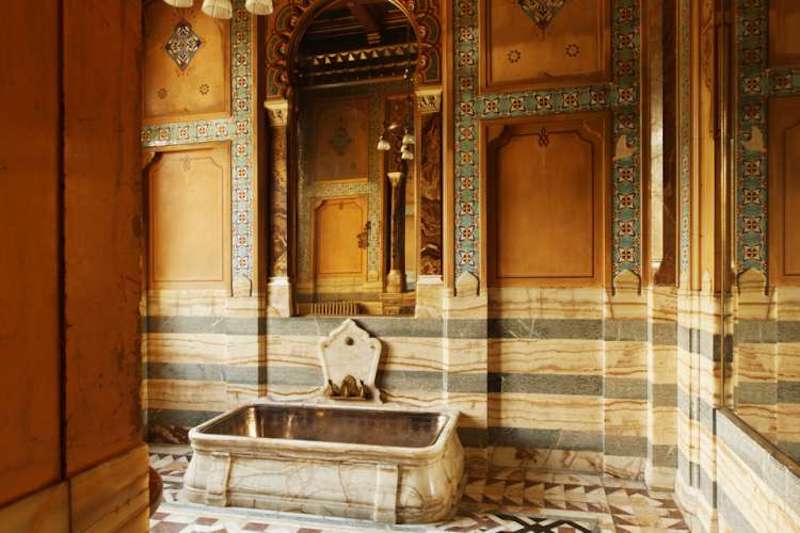

A young Auguste Rodin was hired as one of the sculptors while Paul Baudry, who had just painted the Opera Garnier, got to work on the frescoes. The yellow Algerian onyx staircase is the only one like it in the world and helped classify the mansion as a historic monument. In the Moorish bathrooms, is a magnificent Napoleon III style bathtub, also in yellow onyx, where La Païva is said to have chosen between three taps which released milk, lime-blossom, and champagne for bathwater. The opulent tub has been left intact to this day and there are indeed, three taps.

Her house parties were just as legendary as the décor. As Paris’s most extravagant hostess, she held wild soirées and literary salons attended by the likes of Gustave Flaubert, Émile Zola and Eugène Delacroix. But whether she was very well-liked by any of her guests is another story. She was often heard shamelessly boasting about her obscene wealth, and in her later years, accounts of La Païva are noticeably less flattering.

One count noted, “she is painted and powdered like an old tightrope walker… the reddish hair under her arms showing each time that she adjusted her shoulder straps … [and] she has slept with everyone …”

The Goncourt brothers, diarists of the Second Empire, wrote that, “on the surface, the face is that of a courtesan who will not be too old for her profession when she is a hundred years old; but underneath, another face is visible from time to time, the terrible face of a painted corpse.”

Historically, accounts of courtesans are notoriously unfavourable, and coming from an empire with notoriously loose morals to begin with, we’d be wise to remember to take everything said about La Païva with a pinch of salt. But Paris was soon to be at the centre of the Franco-Prussian War and for its most famous celebrity prostitute, notable investor, architecture patron and collector of jewels, with a Prussian husband to boot, her reign had come to an end. Suspected of espionage, she fled with her Prussian Count to Germany, where La Païva died at the age of 64. Unable to part with his wife, the devastated Count had Esther’s body embalmed in alcohol and stored in the attic of their winter palace – only for his second wife to discover years later.

Back in Paris, the Hotel de la Païva was left empty and abandoned for decades after the war until it found new tenants in 1904. Today, the mansion has functioned as The Travellers Club for over a century, a gentlemen’s club that was all-male until recently and rarely opens up to the public.

Perhaps our favourite room in the house is the Jardin d’Hiver (winter garden), which was recently restored to its former glory in 2018 after nearly a century of neglect.

The gentlemen’s club offers bedrooms on the top floors and private dining rooms for its members, as well as an elegant backgammon lounge and bar beside the winter salon. The mansion can on rare occasions, also be hired for private events, which is how we ended up here.

Its visitor’s book is filled with the names of ex-Presidents, explorers and high-powered businessmen who have sought refuge there and its one of the only places in Paris where one can smoke freely inside. There are still only bathroom facilities for men, and despite being of the wrong sex, it’s unlikely we’ll ever enjoy walking into a men’s room as much as this again…

Tucked away to the side of a restaurant, which now occupies the front courtyard, the quietly existing Hotel de la Païva is a place where time has undoubtedly stopped, in stark contrast to the changing face of the busy Avenue des Champs-Elysées.