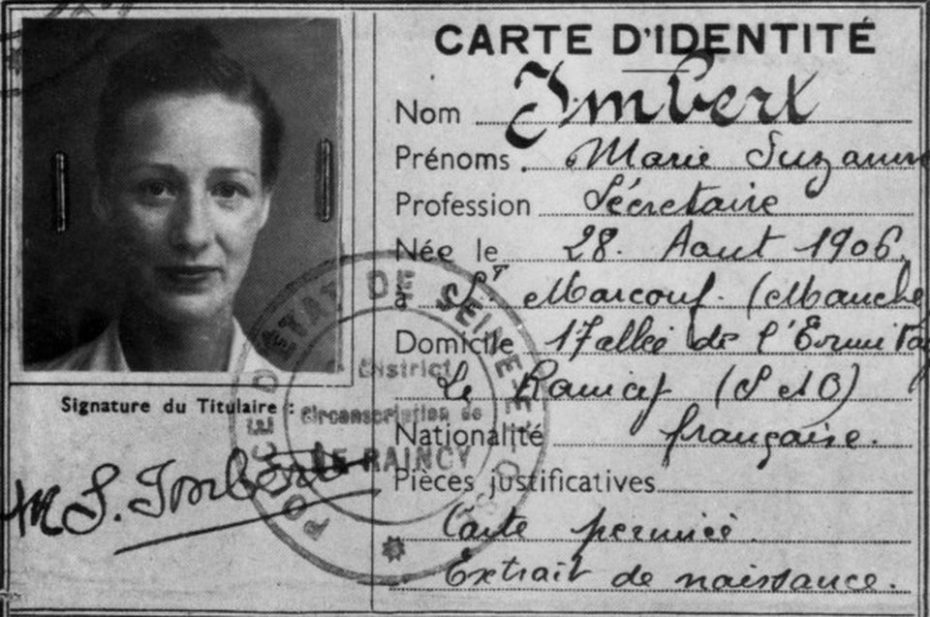

She escaped the Gestapo twice – a glamorous socialite, fashion columnist, pianist and mother of two before the war, she went on to become the only woman to head an underground resistance network against the Nazi Occupation in France. She recruited 3,000 members, 24% of which were women, making it the resistant organisation with the strongest female presence. Her codename was “Hedgehog”. Her real name was Marie-Madeleine Fourcade.

The annals of World War II’s French Resistance network is an often overlooked trove of ordinary people that became extraordinary people in extraordinary times. Marie-Madeleine Fourcade was born into a conservative bourgeois family, went to catholic school and studied music before becoming a young bride to a French officer. She found a career reporting on fashion and produced her own Parisian radio show with none other than the famous French writer and feminist, Colette.

By this time, the young mother had already separated from her husband and was leading a liberated and independent lifestyle in 1930s Paris, having left her two children in the care of their grandmother. But keeping her children away from her was a choice that likely saved their lives in the years to come.

In 1936, Marie reconnected with a former classmate, Georges Loustaunau-Lacau and as war loomed in Europe, she joined him on his journal L’ordre national, a publication aimed at opening French eyes to German aggression. Her role in the resistance began with undertaking secret espionage missions for Lacau to retrieve sensitive documents detailing German intentions in Europe, becoming his closest aid. By the time the war had broken out, Lacau was working undercover in the French Vichy regime for the British MI6 agency. While recruiting agents for a resistance organisation that would later become known as “The Alliance”, he was arrested, leaving Marie to become head of the underground intelligence network he had started.

Her first mission was to recruit and assign agents to sections of unoccupied France, many of whom were ordinary citizens who had little training, which made the work incredibly risky. The Nazis were on a fierce hunt for spies and had numerous high-level resources at their disposal dedicated to locating suspicious radio transmissions and signals. The Germans nicknamed the network “Noah’s Ark”, after the animal code names Marie had assigned to the members. For herself, she chose, “Hedgehog” based on the Beatrix Potter character, an animal that when threatened, rolls up in a tight ball, pointing its spines outwards at the enemy.

The Alliance’s untrained agents made frequent mistakes and hundreds were captured, tortured and killed, but they also succeeded in providing a crucial amount of accurate intelligence to the MI6. Gathering information about German movements and logistics inside France, one of her most successful female agents, Jeannie Rousseau, notably convinced a Wehrmacht officer to draw a rocket and a testing station, revealing the V2 rocket program to the Allies and saving thousands of lives.

Marie smuggled herself across borders inside mail sacks for hours at a time in the boot of cars to deliver intelligence to the MI6. She escaped from the clutches of the Gestapo twice. The first time was in Marseille, when the Gestapo rounded her up with members of her staff. Marie played on her captors’ ignorance, banking on their underestimation of women as domestic servants that were unlikely conspirators in the resistance networks, let alone the boss of one. In reality, Marie hadn’t seen her husband or her own children in years, knowing it would be too dangerous to care for them, let alone see them. During the war, she had a third child with a French Air Force pilot Leon Faye. On rare occasions, she arranged for her family’s caretakers to walk her estranged children in front of the safe houses where she would be hiding just so she could catch a glimpse of them.

The second time Marie escaped arrest was a much closer call and far more extraordinary story. In a Gestapo prison in Aix-en-Provence, she considered taking cyanide that she’d kept hidden on her in case of capture, but knew by doing so, she would be sentencing the rest of her remaining agents to death as well. In her cell, there was a small barred window with wooden boards to let in a small amount of air and light. When her guards went off duty in the small hours of the morning , she stripped naked and began forcing her petite body through an impossibly tight opening. After a few failed and excruciatingly painful attempts, Marie had made it out, clutching her dress by her teeth, bloody and bruised. Dodging the flashlight of a guard who had heard noises, she darted across the street to find refuge inside the mausoleum of a cemetery. She later found a small creek to wash her wounds and lose the scent of blood that would surely put German search dogs on her trail.

To reach a nearby safe house, she had to sneak past her prison again through the streets of Aix at dawn. On the outskirts of town, she joined a group of peasant women in the fields and pretended to pick up corn with them as German soldiers passed by, halting motor traffic to check papers, paying no attention to the women working on the harvest. Marie eventually reached the farm where her fellow agents were hiding. Had she not made it, they would have all been executed by the day’s end.

Fourcade returned to Paris just before the city was liberated in August of 1944 and continued gathering intelligence for the US army on they enemy’s as they retreated from France. She was 35 years-old. Marie lost 438 of her 3,000 agents during the course of the war but dedicated the rest of her life helping the families of those who had died, as well as the survivors. No other Allied spy network had been as successful and long-lasting as hers.

Marie was later presented with one of the British government’s highest honours and upon her death in 1989, she became the first woman to be given a funeral at Les Invalides where the Emperor Napoleon’s tomb lies. Marie-Madeleine Fourcade’s modest tombstone stands today at the Père Lachaise cemetery in Eastern Paris, her name and empowering true story having slipped through the cracks of time. We can find echoes of her unbelievable bravery in fictional characters like Margaret Atwood’s dystopian heroine in A Handmaid’s Tale, but real-life examples of such fearless women are hiding everywhere in the footnotes of history. It’s just a matter of looking.

Fourcade wrote a memoire of her wartime experience in the book “Noah’s Ark“, published in 1968.